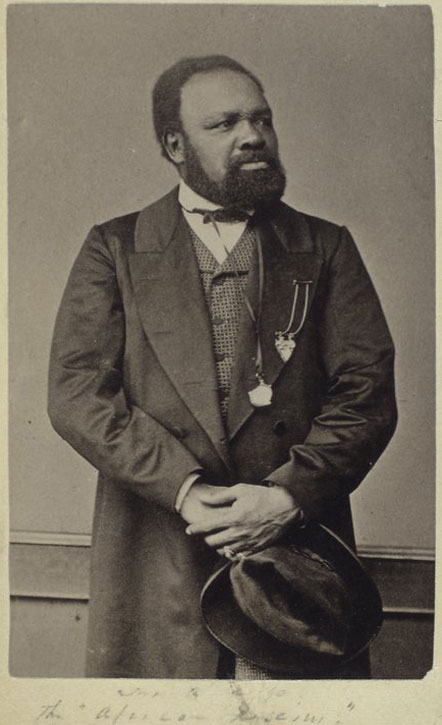

The story of the African-American actor Ira Aldridge (1807–1867), who settled in Europe and became one of the most celebrated Shakespearean actors in history, is one that continues to complicate our understandings of racial attitudes in the nineteenth century.

Aldridge became the first Black man to play Othello in Shakespeare's eponymous tragedy in Britain, allowing him to become a visible and politically loaded symbol against the backdrop of the abolitionist movement.

Image credit: New York Public Library, Digital Collection

Ira Aldridge

Although the Slave Trade Act of 1807 rendered the trading of enslaved peoples illegal in the British Empire, slavery in the colonies still persisted while Aldridge performed in British theatres, meaning his celebrity caused disquiet amongst factions of the wealthy elite and those who continued to profit from the system.

Aldridge's impact on European society can be detected in countless artistic depictions in UK collections and abroad, demonstrating his theatrical range and versatility across many decades. Although not all art historians agree on which paintings can be confidently identified as him, the following works have helped to preserve his legacy and tell us more about the reception of a prominent Black figure during a turbulent era.

Born in New York on 24th July 1807 to free African Americans, his father was a reverend at a local Black church and encouraged his son to follow in his footsteps. Aldridge studied at the New York African Free School, where he cultivated an interest in theatre. Founded by the Manumission Society and abolitionists such as Alexander Hamilton, the institution intended to educate the children of enslaved individuals and free people of colour.

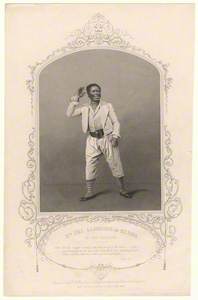

As a teenager, Aldridge became affiliated with a Black theatre community in lower Manhattan, and by the age of 15, he joined the short-lived African Company, founded by the playwright William Alexander Brown (also known as William Henry Brown) in 1821. The co-creator of the theatre group was the acclaimed African-American thespian James Hewlett who starred in Shakespearean plays such as Richard III.

Image credit: African Grove Theatre, New York

James Hewlett as Richard the Third, African Grove Theatre

1821–1831, coloured drawing by unknown artist

But due to extreme racial discrimination in the United States, and 'finding no adequate outlet for his ambition in New York' according to his biographer Bernth Lindfors, Aldridge decided to set sail for Britain in 1824. He was fortunate enough to secure work at London's Royal Coburg Theatre (now known as the Old Vic) and performed under the name 'Mr Keene, Tragedian of Colour', in homage to the most famous stage actor of the time, Edmund Kean.

While both Aldridge and his reviewers downplayed his American identity, Aldridge emphasised his African heritage, allowing it to become part of his theatrical trademark. In 1825, at the age of 17, he debuted as Othello in a small London theatre and continued to star in abolitionist melodramas. He became known as a brilliant tragedian and comedian on stage and was dubbed the 'African Roscius' (referring to the great Roman actor) by enthusiastic theatre reviewers but also Aldridge himself.

The British public's reception towards Aldridge was mixed. While his fame and popularity swelled, he was also shunned and ridiculed for his accent, mannerisms and skin colour. One scathing (and racist) review for The Times claimed that: 'His figure is unlucky for the stage; he is baker-knee'd and narrow-chested; and owing to the shape of his lips it is utterly impossible for him to pronounce English in such a manner as to satisfy even the fastidious ears of the gallery.'

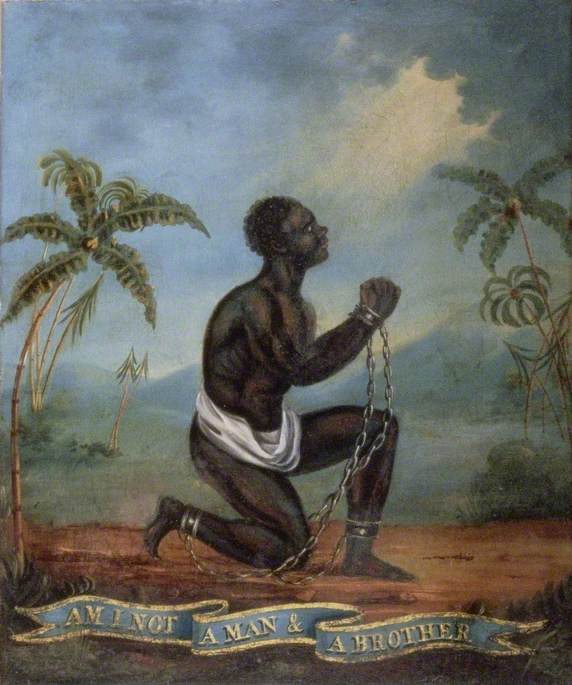

Image credit: Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Oroonoko

1791, engraving on paper by unknown artist

Before earning the part of Othello, Aldridge had been cast as a mythical African prince in an adaptation of Thomas Southerne's Oroonoko, originally created by the seventeenth-century novelist Aphra Behn, a tale belonging to an important lineage of anti-slavery literature that would be followed by popular texts such as Olaudah Equiano's The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano (1789).

Although Aldridge didn't arrive in Britain with the sole purpose of promoting the abolitionist movement, his impressive skill, charisma and oratory capabilities inevitably swayed public opinion. He became known for directly addressing the audience about the injustices of slavery on the closing night of his play at a given theatre.

In 1828, he was invited by Sir Skears Rew, the owner of the Coventry Theatre, to manage and run the dwindling business, becoming the first Black man to take up such a position in Britain. While working in Coventry, he performed pro-abolition speeches and is even credited with inspiring a local petition to Parliament for the abolition of slavery.

In 2017, a plaque dedicated to Aldridge was unveiled in Coventry by actor Earl Cameron who had been trained by Aldridge's daughter, the opera singer Amanda Ira Aldridge (1866–1956).

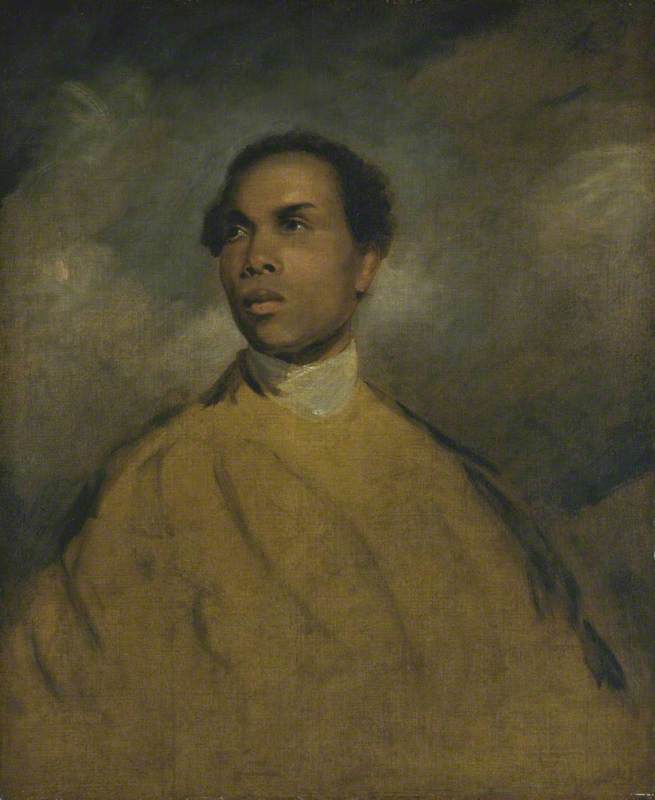

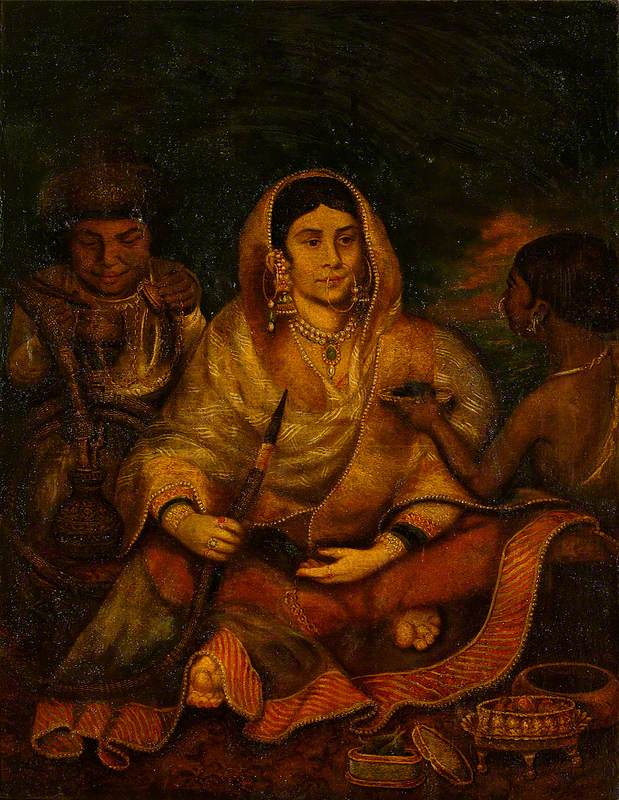

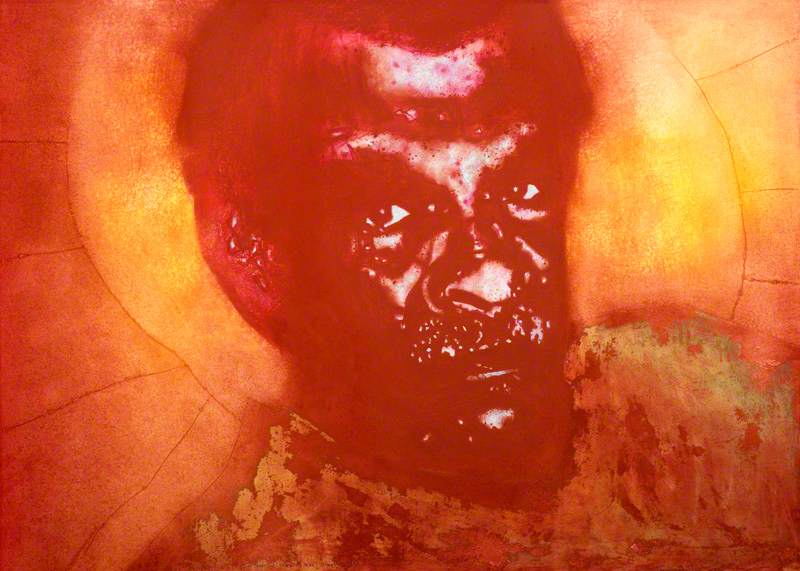

Throughout the early 1820s, Aldridge sat for numerous British artists. James Northcote painted him in 1826 when performing the title role of Othello aged 19.

Northcote's painting was commissioned by the Royal Manchester Institution, shortly after Aldridge's performances at Manchester's Theatre Royal. A pupil and biographer of Joshua Reynolds, Northcote was around eighty years old when he painted Aldridge. The identification of the sitter hasn't always resided with Aldridge –it was previously thought to be Francis Barber, the manservant of Samuel Johnson. However, as Ruth Cowhig has highlighted, Barber is believed to have died in 1801, whereas the reference to Othello and Ira Aldridge as the true sitter seems to be 'firmly based'.

Barber himself is thought to be the sitter in this painting in the Tate collection.

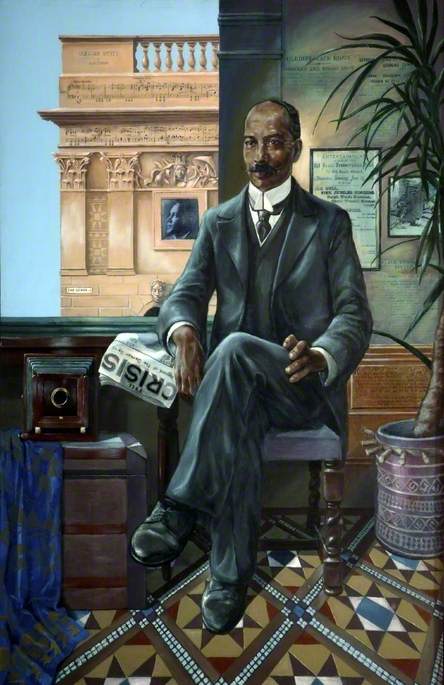

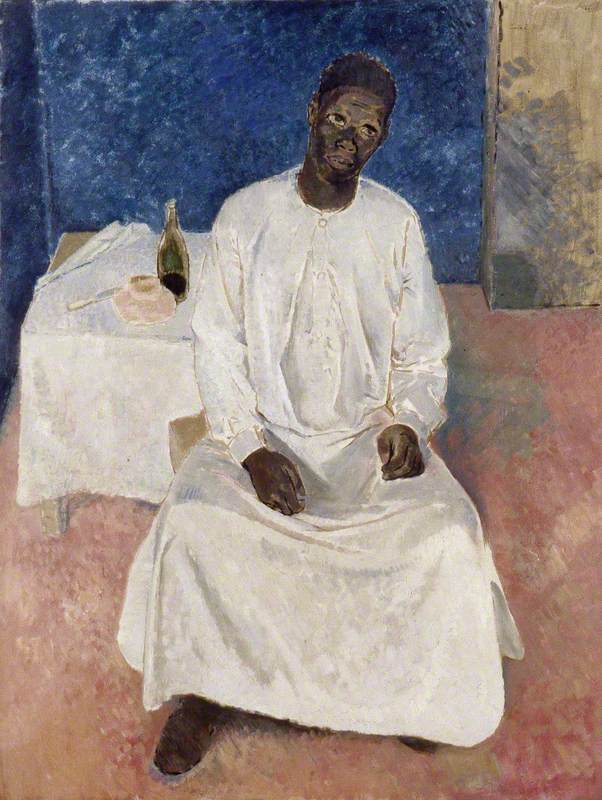

John Simpson's portraits Head of a Man (in Tate Britain) and The Captive Slave (now in the Art Institute of Chicago) are both dated to c.1827. The artist's striking portrait of an enslaved man in chains was first exhibited in London in 1827, and accompanied by lines from William Cowper's 'Charity' (1782), a popular anti-slavery poem.

Image credit: Art Institute of Chicago

The Captive Slave

1827, oil on canvas by John Philip Simpson (1782–1847)

Intended to appeal to the abolitionist cause, the figure and composition evoke Christian iconography of martyred Saints. The shackled figure in red prison garments is framed against a dark background as he sorrowfully looks towards the heavens, resigned to his fate.

Exhibited several years before the decisive Slavery Abolition Act of 1833, the painting would have resonated with the Christian mentality underpinning the abolitionist movement, and was spearheaded by figures such as William Wilberforce and members of the Anglican Clapham Sect.

Both The Captive Slave and Simpson's work Head of a Man (?Ira Aldridge) belonging to Tate's collection are believed to be of Aldridge.

We can affirm this attribution according to Martin Postle, partly because the dates coincide with Aldridge's 'rapid rise to prominence as the first great Black Shakespearean actor on the British stage'. Around this time, Aldridge had starred in Thomas Mortan's The Ethiopian, otherwise known as The Slave. One crucial scene in the play takes place in a prison, after Aldridge's character liberates an imprisoned white captive and subsequently submits himself to slavery once again in a moment of self-sacrifice.

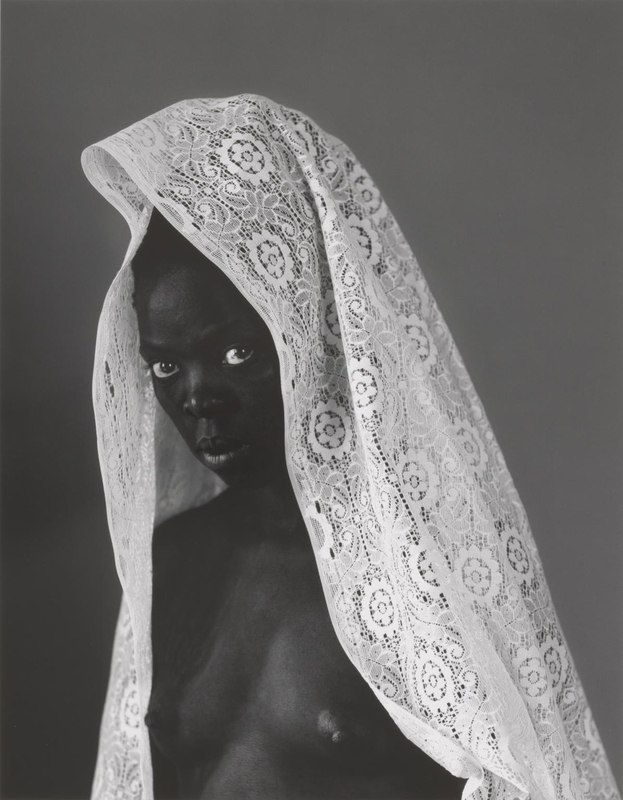

A few years later, the artist Henry Perronet Briggs created this half-length portrait of a figure believed to be Aldridge, who is depicted in theatrical attire and gazes into the distance.

Image credit: National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Ira Aldridge as Othello

c.1830, oil on canvas by Henry Perronet Briggs (c.1791–1844)

Not long after, Aldridge would replace Edmund Kean as the part of Othello at the Covent Garden Theatre, after Kean suddenly fell ill and died in 1833.

A depiction of Kean in the National Portrait Gallery by John William Gear shows the actor with darkened skin as he plays the part of the Moorish general.

Image credit: National Portrait Gallery, London, CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Edmund Kean as Othello

early 19th C, hand-coloured lithograph by and published by John William Gear (1806–1866)

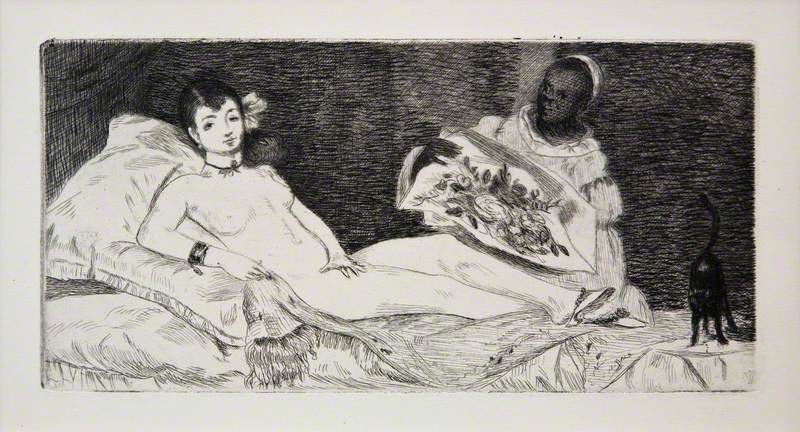

Blackface, or the historic tendency for white stage actors to use dark makeup, flourished during the Shakespearean era, but was popularised in America in the early nineteenth century and typically perpetuated racist stereotypes and caricatures of African Americans. Before Aldridge, only white performers such as Kean had portrayed Othello on stage, and as suggested by Gear's depiction, they darkened their skin using materials such as burnt cork, greasepaint or shoe polish.

After Aldridge's debut at London's most prestigious theatre, some reviewers protested about a Black actor appearing on stage. Nevertheless, The Morning Post praised his performance, writing: 'it was doubtless sufficiently good to be considered very curious'. It is likely that the rare sighting of a person of colour on stage – and not as an enslaved person or servant – fascinated British audiences, especially as Aldridge's eloquence and talent would have undermined racist assumptions underpinning nineteenth-century attitudes.

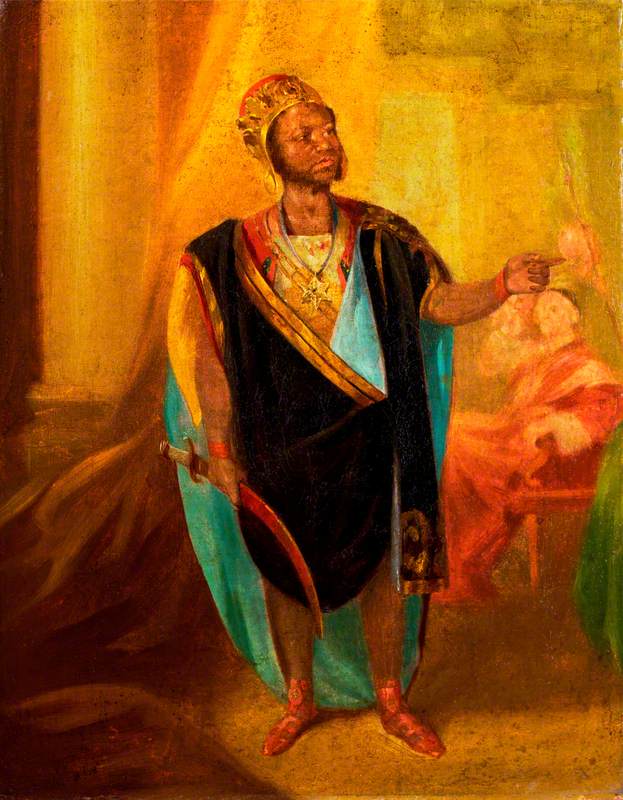

Image credit: Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Ira Aldridge (1807–1867), as Othello in 'Othello' by William Shakespeare c.1848

British School

Victoria and Albert MuseumDue to rising tensions and protests about the abolition of slavery in Britain's colonies in 1833, after only a handful of performances, the theatre closed the play and Aldridge was dismissed. His Memoir recounted: 'Theatres were not doing well, and the "legitimate" business was particularly low. He performed but four nights at Covent Garden; and then his name was withdrawn from the bills.'

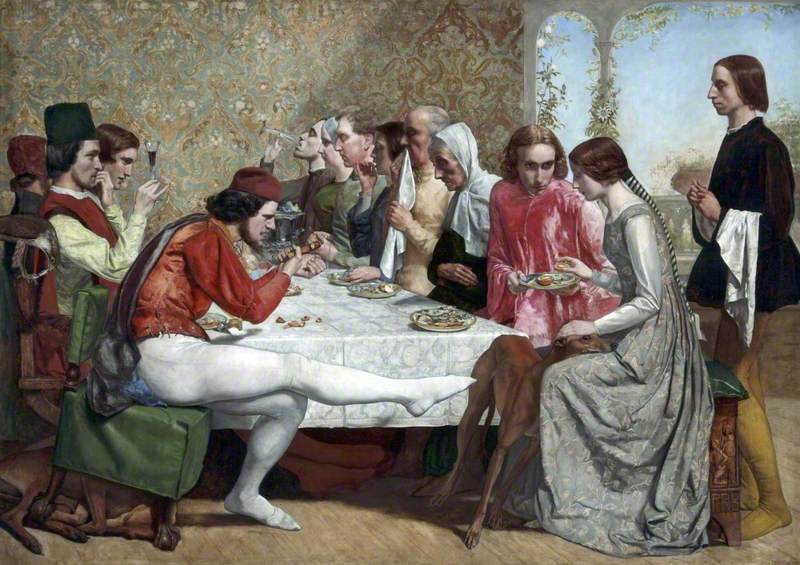

Aldridge continued to perform the part of Othello in regional theatres, evidenced in part by the fact that a number of years later, the Irish artist William Mulready captured a Black figure presumed to be Aldridge in battle armour.

Image credit: Walters Art Museum, public domain (source: Wikimedia Commons)

Othello

c.1840 and 1863, oil on panel by William Mulready (1786–1863)

In 1850, his autobiography Memoir and Theatrical Career of Ira Aldridge, the African Roscius was published. The book detailed aspects of both his personal and professional life, describing his voyages across the country: 'acting in succession at Brighton, Chichester, Leicester, Liverpool, Glasgow, Edinburgh, Exeter, Belfast and so on, returning to London after a lapse of seven years...'

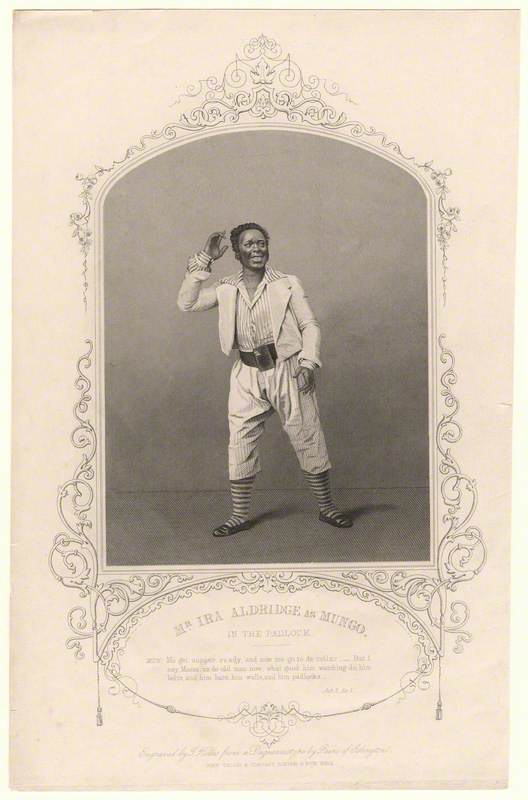

Image credit: Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Ira Aldridge (1807–1867), as Mungo in 'The Padlock' by Isaac Bickerstaffe c.1833

Thomas Charles Wageman (1787–1863)

Victoria and Albert MuseumAround the same time, both this painting and engraving show Aldridge in one of his most famous roles, as Mungo in the operetta The Padlock by Isaac Bickerstaffe. In his role as a servant from the West Indies, Aldridge sang, danced and played guitar. According to the National Portrait Gallery, he became known for 'mixing protest with comedy'.

Image credit: National Portrait Gallery, London

Ira Frederick Aldridge as Mungo in 'The Padlock' (after William Paine) published c.1850

T. Hollis (active mid-19th C)

National Portrait Gallery, LondonAnother engraving in the National Portrait Gallery presents him during a performance at the Britannia Theatre, Hoxton in 1852, where he plays the role of Aaron, a Moor, in Shakespeare's violent tragedy Titus Andronicus.

Image credit: National Portrait Gallery, London

Ira Frederick Aldridge as Aaron in 'Titus Andronicus' published c.1850

William Paine (active 1849–1858) (after)

National Portrait Gallery, LondonAldridge spent much of the 1850s on the Continent, touring the Austro-Hungarian empire, Germany, Prussia, Switzerland, Poland and eventually travelling to Russia in 1858 where he was well received. Upon returning to England in the 1860s, he applied for British citizenship.

His personal life was just as eventful as his professional one – although his wife, Margaret Gill, bore no children, it is believed that he fathered at least six children by three other women, one of whom became his second wife. Two of his daughters, Luranah and Amanda, became professional operatic singers.

By the time of his death in 1867 in Lodz, Poland, Aldridge was an acclaimed and award-winning stage actor and the most visible Black figure in Europe. He had appeared on stage in more than 250 theatres across Britain and Ireland, and more than 225 theatres in Europe. According to Zoë Wilcox, Curator at the British Library: 'his professional career was spent continuously touring because theatre managers would not employ him for longer periods, meaning that he was probably seen by a wider variety of people than any other Shakespearean actor of the day.'

During his lifetime, Aldridge successfully challenged preconceived notions about the capabilities of Black people, but unfortunately his legacy faded from public consciousness after his death, though African-American actors sought to preserve his memory and regarded him as an inspiration model.

In 2012, the award-winning play Red Velvet written by Lolita Chakrabarti and starring Adrian Lester opened in London, and successfully pushed Aldridge's life back onto the centre stage.

Lydia Figes, Content Editor at Art UK

The Manchester portrait of Aldridge is available to buy on the Art UK Shop

Further reading

Bernth Lindfors, '"Mislike Me Not for My Complexion...": Ira Aldridge in Whiteface', African American Review, 2017

Bernth Lindfors, Ira Aldridge, 2021

Ruth Cowhig, 'Northcote's portrait of a black actor', The Burlington Magazine, December 1983

Martin Postle, 'The Captive Slave by John Simpson (1782–1847): a rediscovered masterpiece', British Art Journal, (Vol. 9, Issue 3), 2009

'The Life of Ira Aldridge', Chicago Shakespeare Theater teaching resource

Abdul Rob, 'Ira Aldridge', Black History Month UK, 2016

Zoë Wilcox, 'The actor who overcame prejudice to win over audiences', BBC, 2016