The current show at the British Museum, 'Inspired by the east: how the Islamic world influenced western art' (10th October 2019 – 26th January 2020) has prompted a reconsideration of the concept of 'Orientalism' and its ubiquitous presence in art history.

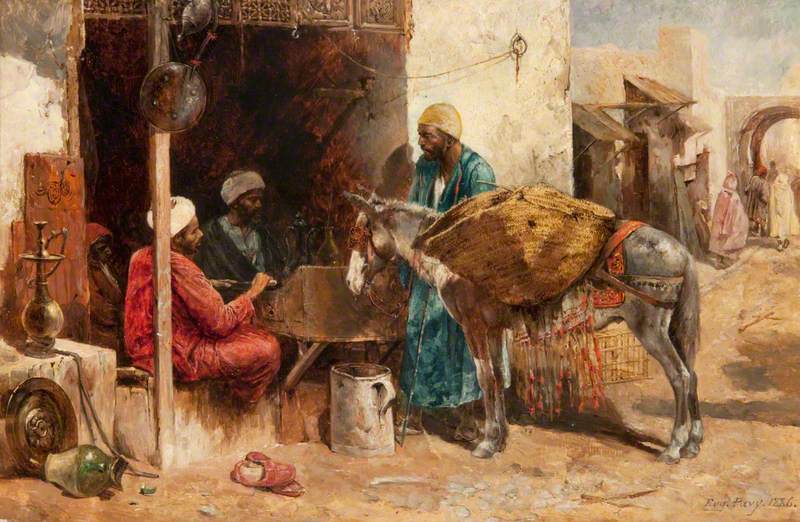

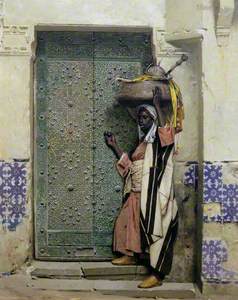

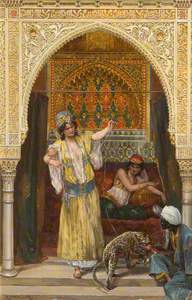

An Eastern Doorway; At the Moslem Chief's Door

1887

Raphael von Ambros (1855–1895)

In our globalised world, the idea of 'othering' another culture might seem strange to some – though in fact, it still exists. Historically speaking, Europeans and North Americans alike viewed 'the east', as it was once termed, as an idealised fantasy.

What is Orientalism?

'Orientalism' is a term that describes how Europeans represented unexplored territories in regions of the eastern or Islamic world. Places like Turkey, Greece, the Middle East and North Africa were framed as exoticised, fictionalised places.

Postcolonial theorist, Edward W. Said, brought discussions about 'Orientalism' to the fore in his initially controversial book published in 1978, which exposed the imperialist lens with which Europeans sought to contain, control and fetishize the splendours of the 'Orient'. Amongst many other things, Said argued that European colonial culture deliberately contrasted itself to the Islamic world, in order to affirm a self-fashioned, superior identity.

'Orientalism as a Western style for dominating, restructuring, and having authority over the Orient.' – Edward W. Said

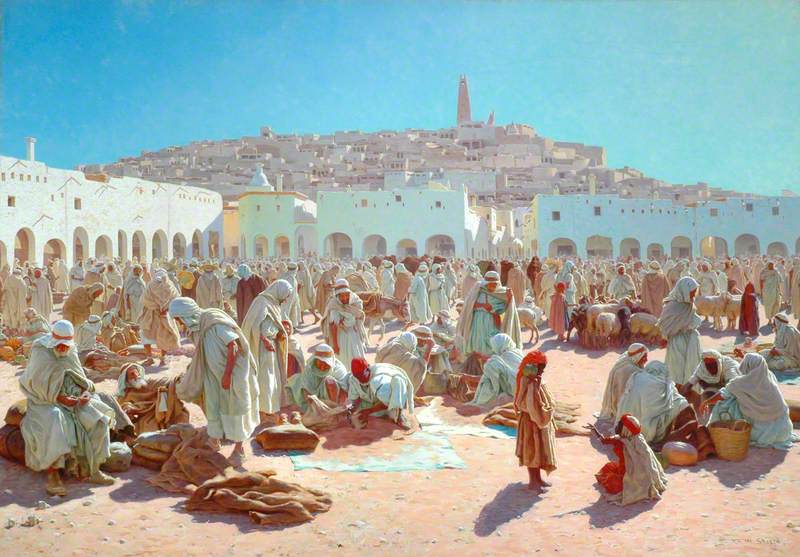

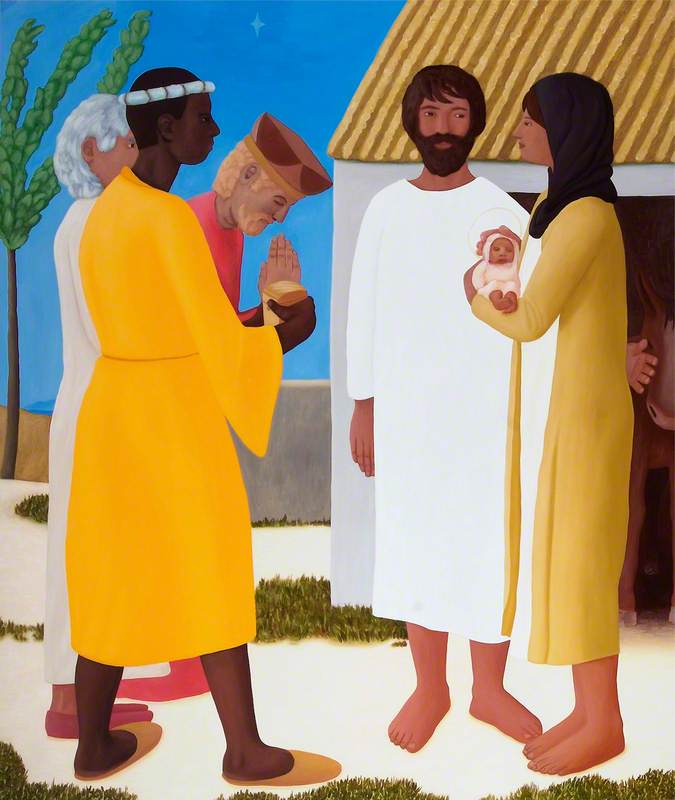

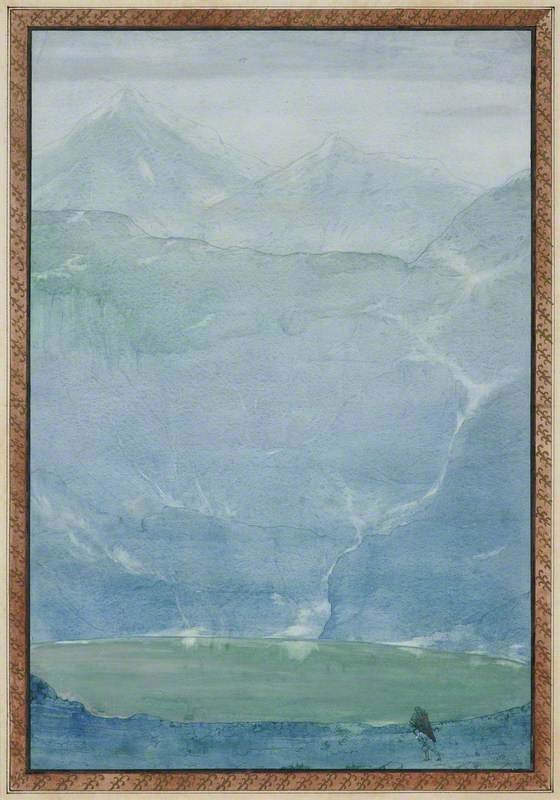

During the height of colonial empires in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, European artists and writers travelled to the Middle East and Africa in search of adventure and new discoveries. While on their voyages, these individuals recorded what they witnessed from their own foreign perspectives. From this context, the 'Orientalist' manner of painting came to prominence – an aesthetic subject and style that highlighted 'eastern' subject matters favoured by Europeans: the harem, the bazaars, or ornate domestic interiors.

Orientalist art history propagated a myth of the Middle East and Northern African ('the east') as a romanticised, exotic landscape, albeit one that was undeveloped, primitive and ruled by tyrannical despots. Such images evolved into powerful stereotypes that crossed cultural and national boundaries, and still underpin racist assumptions today.

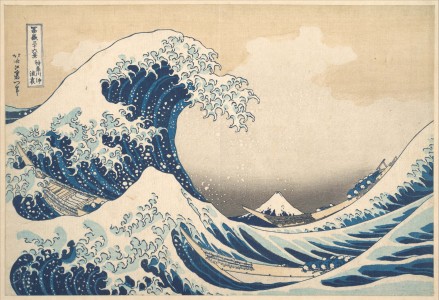

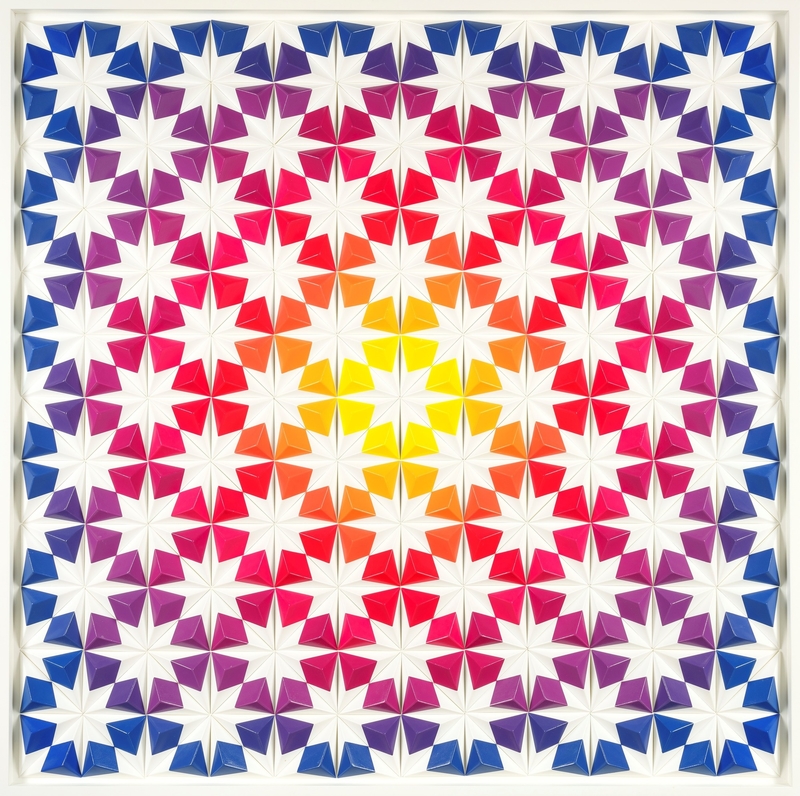

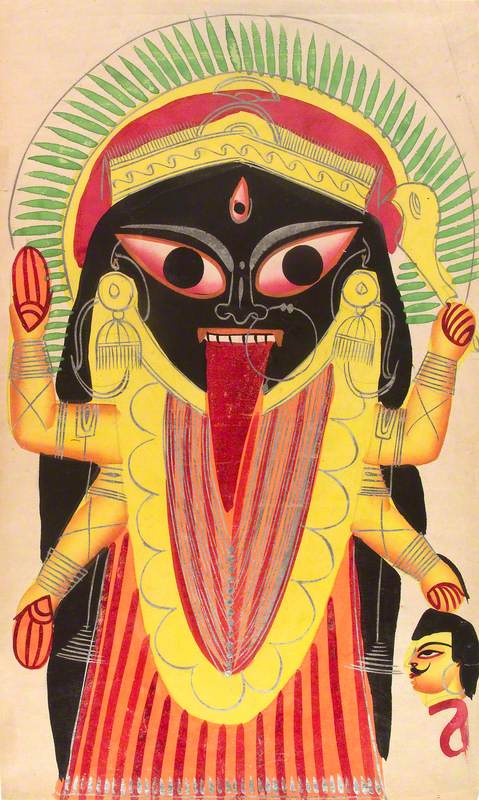

But 'Orientalism' as an ideological structure and binary worldview that divides 'east' and 'west' extended further afield to India, China and Japan. Artists of these countries adopted an 'Occidentalist' approach to art in reaction to western imperial and colonial representations.

Fiction or reality?

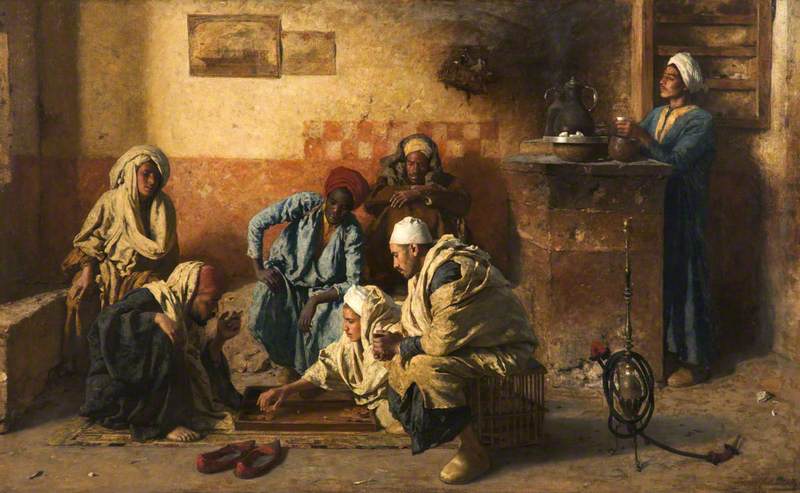

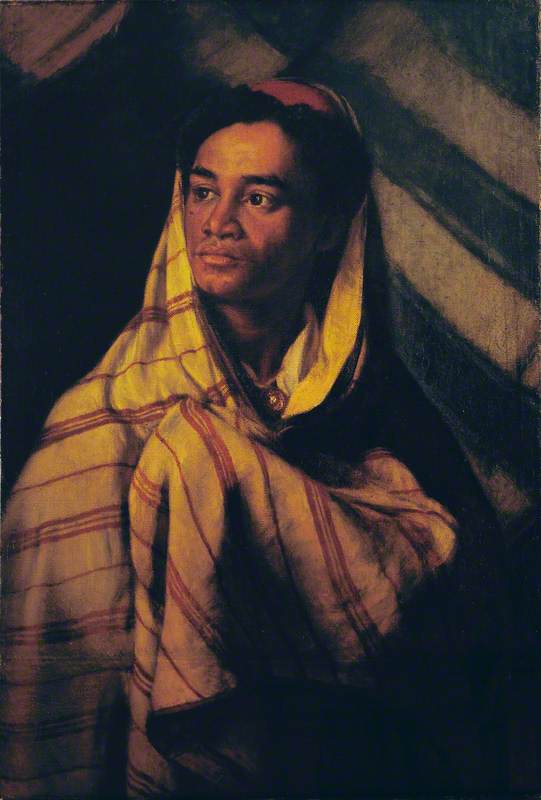

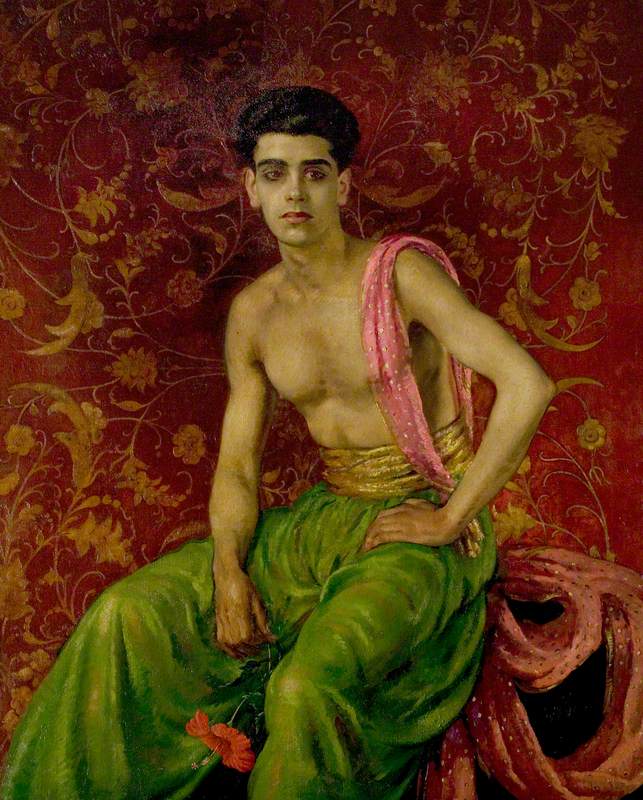

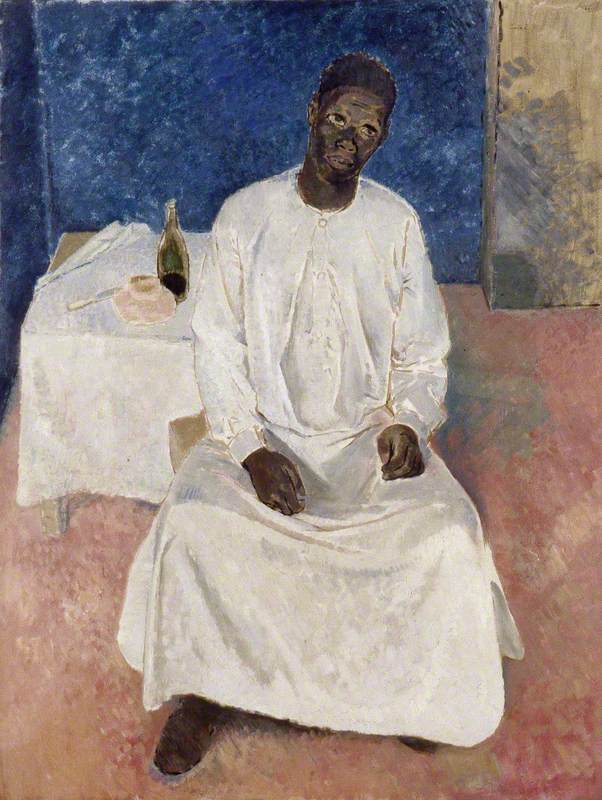

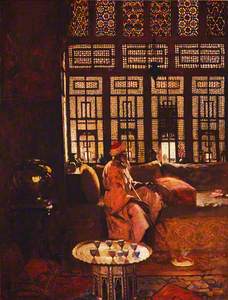

The most prevalent form of Orientalist art in the nineteenth century was genre painting, in which people were often depicted working or relaxing. It was greatly influenced by the artist's direct or imagined experience of everyday life in the east, one that would appear rose-tinted when captured in painting.

Ferencz Eisenhut (1857–1903) had a reputation for 'authentic' depictions of eastern life. This languid scene, in a rustic room, shows a teacher struggling to keep the attention of his pupils; perhaps conveying that the temperature was too hot, or that he was a poor educator.

Leopold Carl Müller (1834–1892) was an Austrian painter who travelled to Egypt many times. Here a group of Egyptian men are engrossed in playing backgammon, but at a time when there was great political instability in the country.

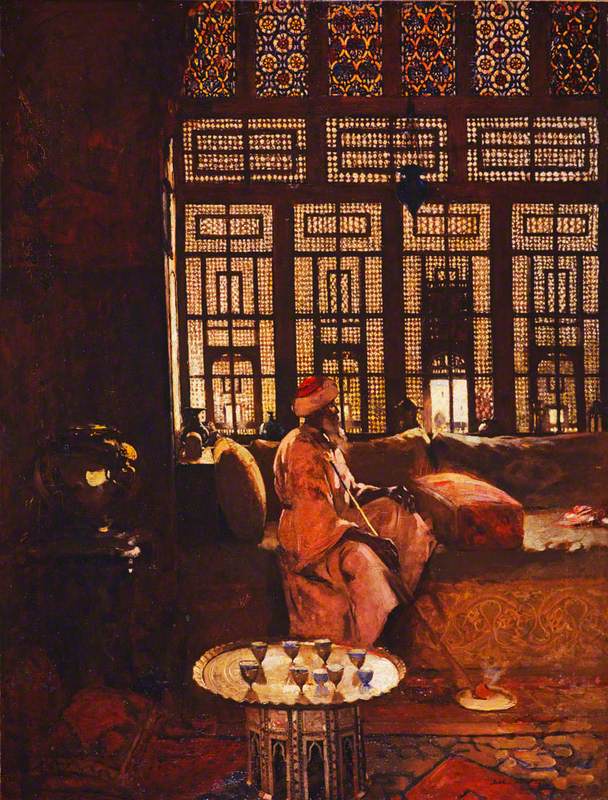

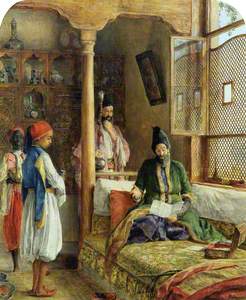

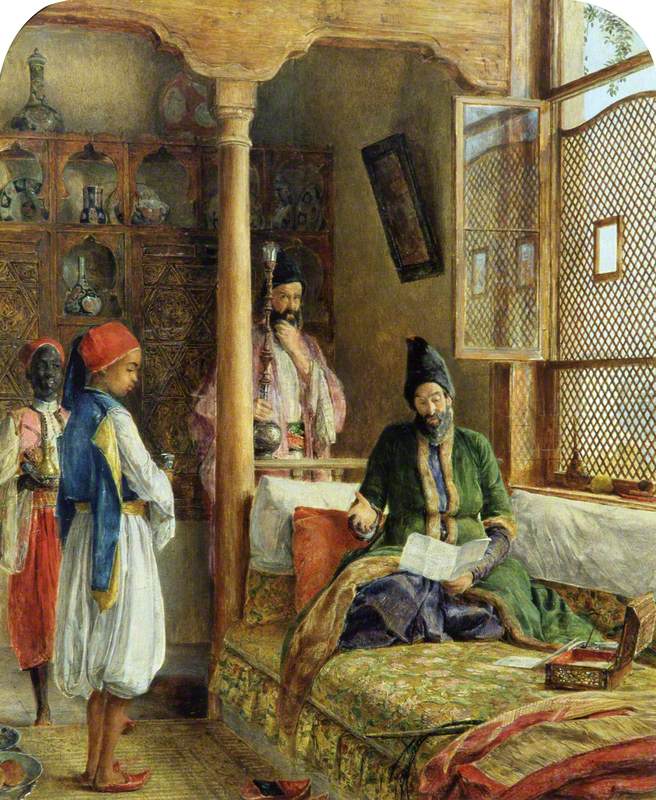

The paintings of John Frederick Lewis (1804–1876) were highly detailed and colourful, with careful representations of Middle Eastern interiors, architecture, furnishings and people wearing native clothing.

An Oriental Interior (A Startling Account, Constantinople)

1863

John Frederick Lewis (1804–1876)

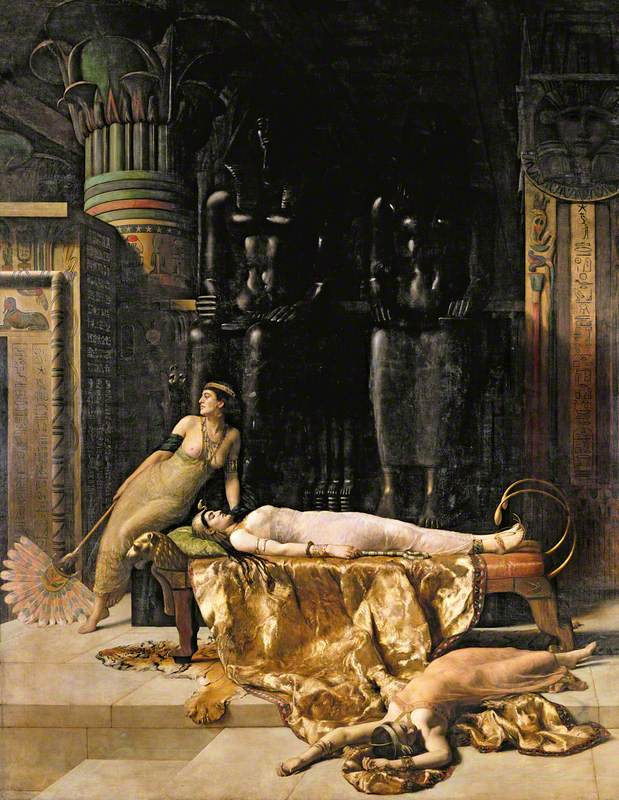

Women: submissive or strong?

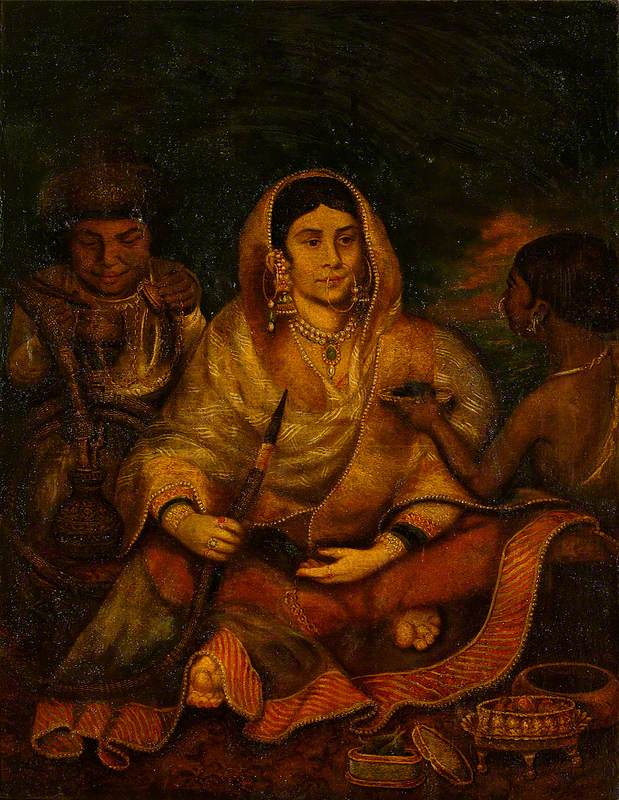

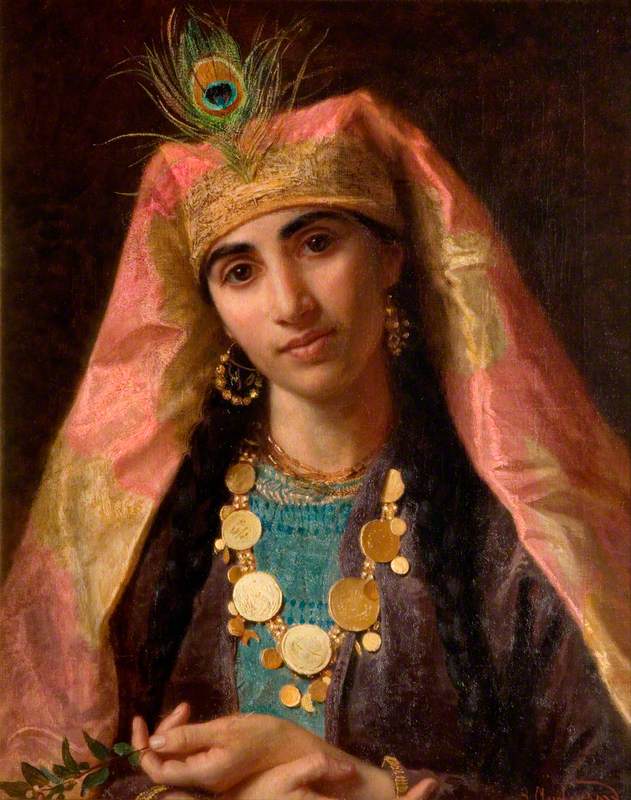

Oriental art from the nineteenth century typically depicted partially clothed or nude women: concubines, odalisques or peasants. In Orientalism, Said elucidated on the artistic tradition of objectifying the 'exotic' woman – a sought-after subject matter for British and French artists during this era.

'Flaubert's encounter with an Egyptian courtesan produced a widely influential model of the Oriental woman; she never spoke of herself, she never represented her emotions, presence, or history. He spoke for and represented her.' – Edward W. Said

As Said argues, the 'Orientalised' woman is portrayed as being domesticated, submissive and unable to speak for herself. She has no power or agency, so, therefore, can be read as a metaphor for the nature of colonization itself.

On the other hand, artists such as Lewis presented clothed women in situ amongst ornate domestic settings, rather than as sexualized, nude objects seen in paintings by artists like Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780–1867). Lewis was a prolific English artist who travelled extensively around the Mediterranean and North Africa.

Like many other European artists, Lewis depicted the harem in several of his paintings. A private domestic space usually for maintaining the modesty, privilege, and security of wives, concubines, and female servants, the harem provided a voyeuristic setting irresistible to male artists and patrons. The interior design and decoration of these harems were usually somewhat embellished, to appeal to the European imagination.

Lewis asserted that – unlike other Orientalist painters – he 'never painted a nude'. In fact, his wife apparently modelled for several of his harem scenes.

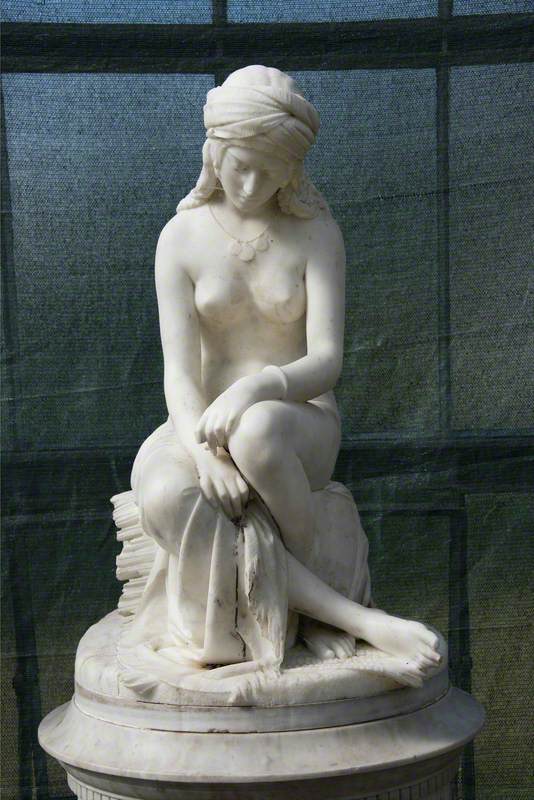

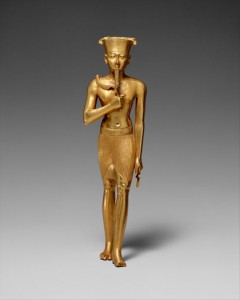

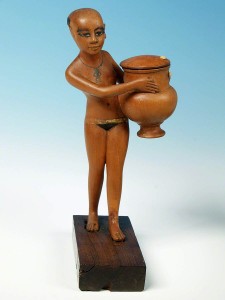

In contrast, this sculpture was inspired by the area of ancient Nubia, now part of southern Egypt and northern Sudan. The sculptor worked in Rome and gained a reputation for 'fantasy' pieces in white marble. This is an idealised nude young woman with European features, sitting on a stone looking down helplessly.

A successful Austrian entrepreneur, Friedrich Goldscheider (1845–1897) produced many terracotta, faience, bronze, and alabaster ceramics and objects. This woman is balancing a basket on her head, and looking as if she is about to speak.

Originally from Australia, Mary Cowie Nichols (1837–1928) painted a variety of scenes not limited to the Oriental style. She created a strong identity for this sultry raven-haired woman. In ornamental red and black clothing, Fatima is about to draw back a deep red velvet curtain and unlatch a door.

An Oriental Woman: Fatima

(after John Frederick Lewis)

Mary Cowie Nichols (1837–1928)

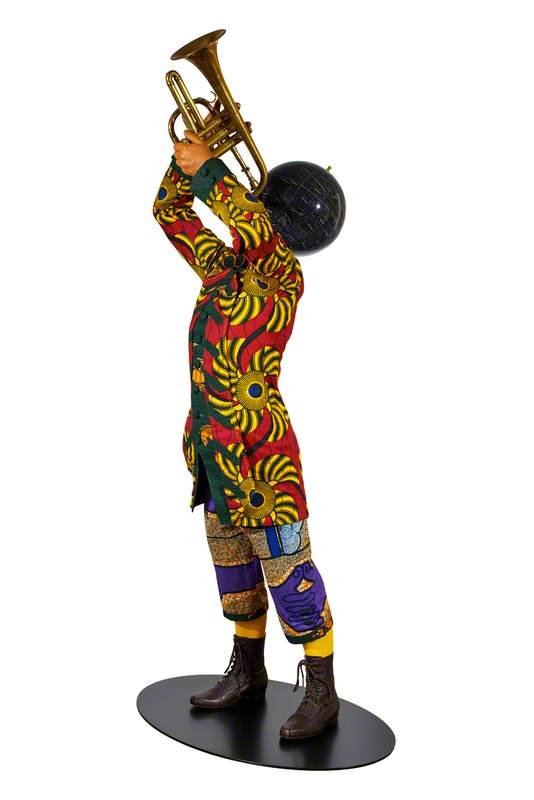

To challenge Orientalism means to reject racialised stereotypes, preconceived judgements, and cultural and religious bias. It doesn't mean denying differences between east and west, but understanding the still-existing colonial power dynamics and analysing differences in a more sensitive and objective manner. Today, with a bit of context, and the benefit of hindsight, we can decide for ourselves the validity of these artworks.

Nancy Lyons, researcher and writer