The year 1949 was a transformative one for art in India. Two years after Britain's withdrawal from the subcontinent and the birth of the world's largest democracy, a fine arts faculty was created at the Maharaja Sayajirao University in Baroda in Western India.

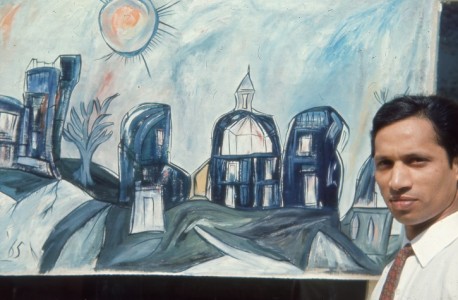

This strikingly domed building, regal in its splendour, instantly grew into an incubator of aspirations: suddenly, art could be looked upon as a vocation. Eschewing the European traditions introduced to India by British schools, the faculty in Baroda borrowed the tenets advanced by poet and 1913 Nobel prizewinner Rabindranath Tagore's radical open-air school of cultural learning Shantiniketan, as well as the Bauhaus and the Barnes Foundation.

In a period of post-colonial identity building, the school was conceived as a bridge between the 'Oriental' and the 'Occidental', with courses that combined the theory of art history with studio practice.

A novel programme required formidable leadership and teachers with pedagogical values. K.G. Subramanyan embodied both. Following his appointment to the painting department in 1951, he proceeded to define the school's character by imbuing it with the vision of his former teacher Binode Bihari Mukherjee, a pioneer of modern art in India.

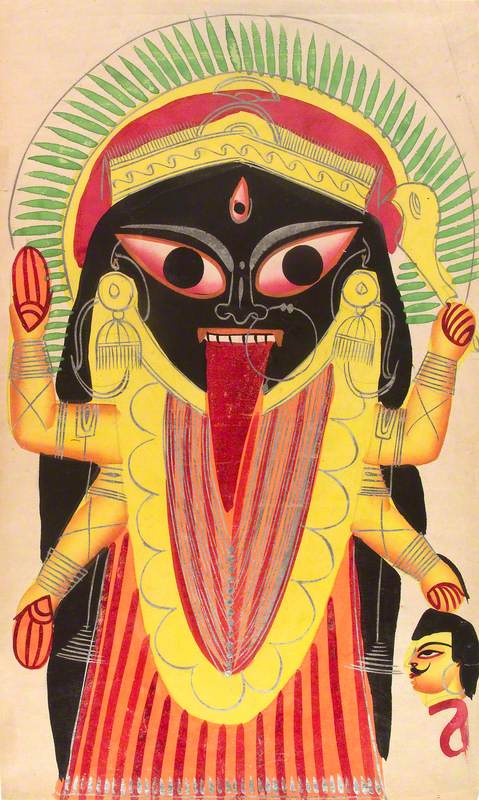

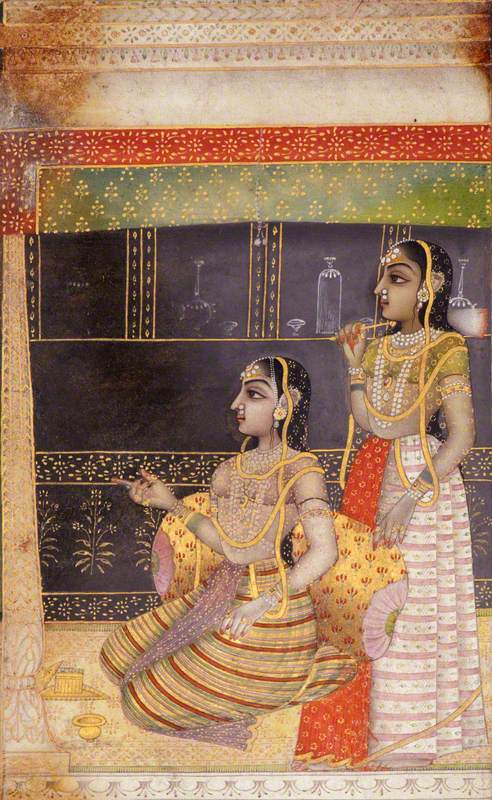

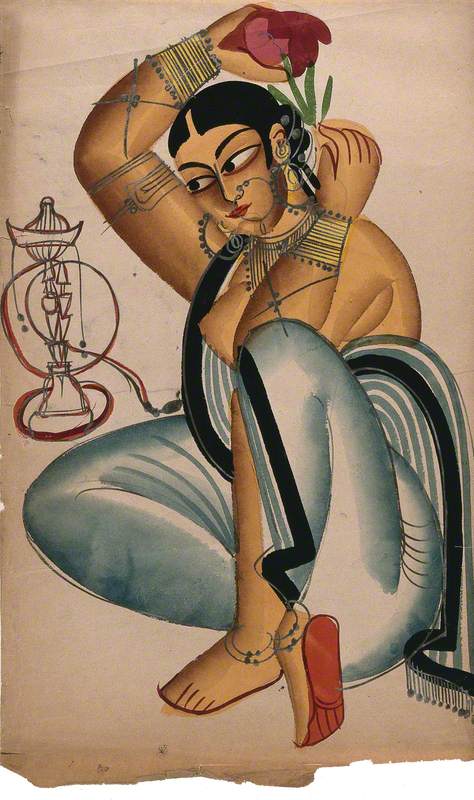

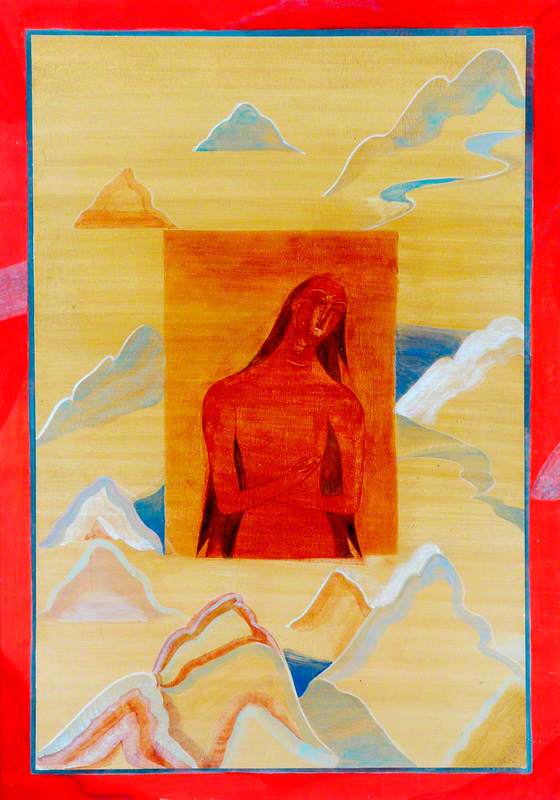

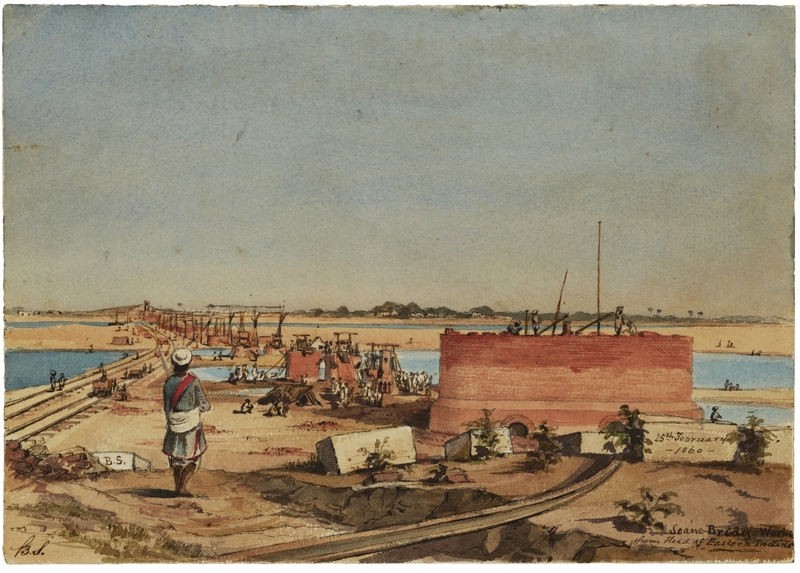

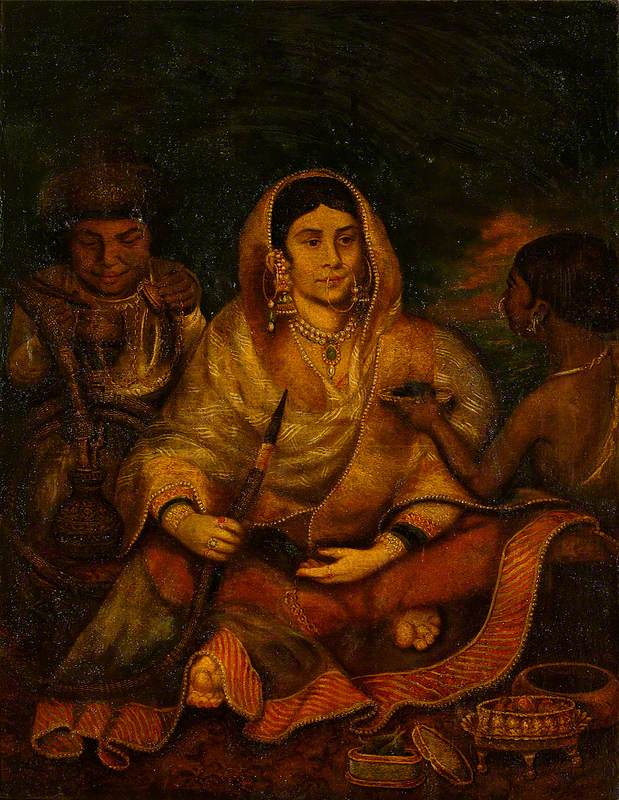

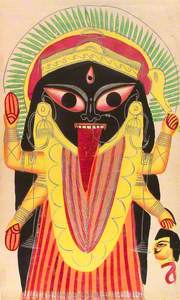

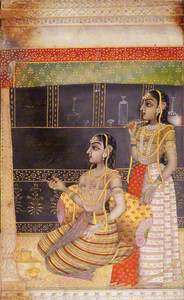

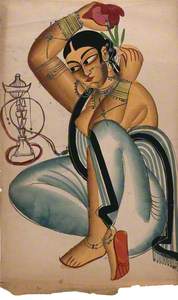

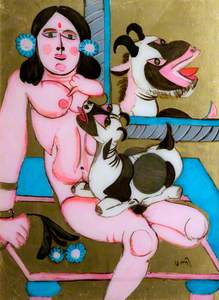

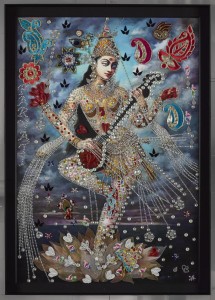

Spurred by Mukherjee's emphasis on Indian folk and classic styles such as boisterous Kalighat painting (shown above) and delicate miniatures (shown below), Subramanyan placed a commitment to 'Living Traditions' at the centre of the curriculum.

An eclectic conglomeration of styles and techniques was available across India, and Fine Arts Fairs conceived by Subramanyan in 1961 enabled him to introduce them to the students.

The fairs were exciting events that converted school grounds into artistic spaces replete with stalls of makers and their mediums. Weaving, ceramics, wood and metalwork were demonstrated. With all the vibrancy of a melā (the Sanskrit word for 'gathering' or 'fair'), performances with traditional masks were put on and students were encouraged to sell their own smaller works. This was the foundation for experimental making, which inspired talents like the sculptor Mrinalini Mukherjee.

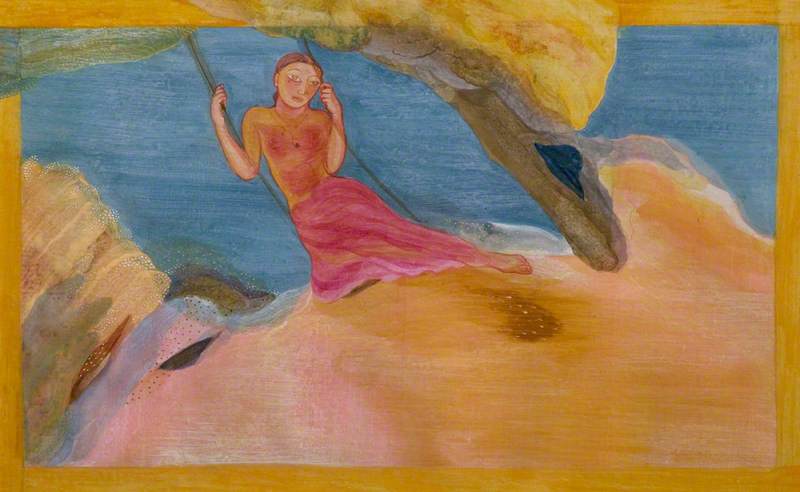

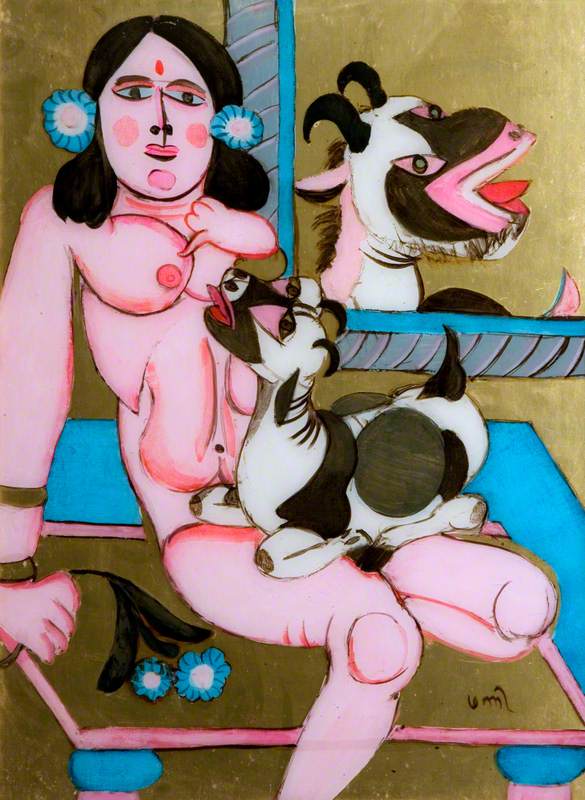

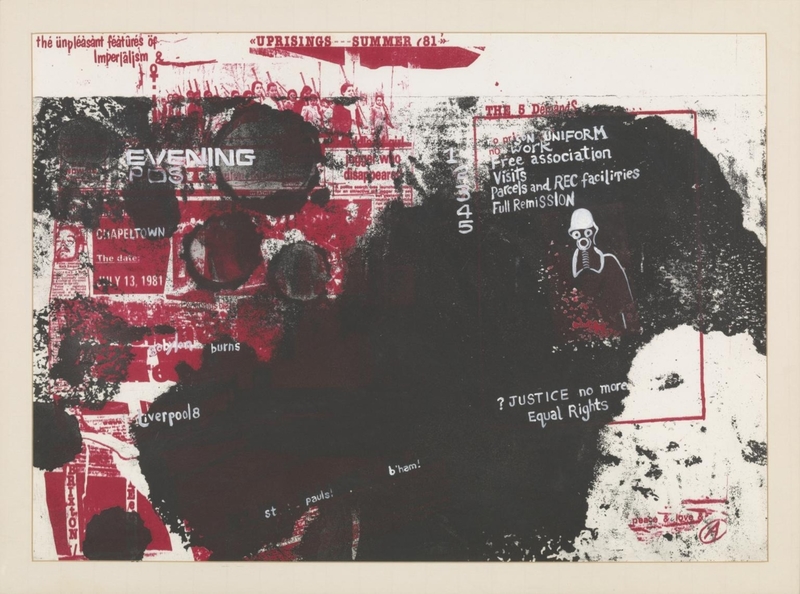

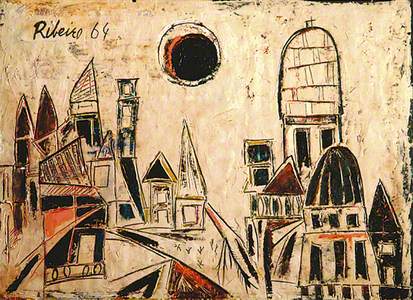

These were also formative years for Subramanyan, who not only capitalised on craft, but in many ways revitalised the industry. Goats, Woman (1981), a lusty claustrophobic scene, riffs off the dynamic Kalighat style from Calcutta in West Bengal.

In the tightly framed A Courtesan Arranging a Flower in her Hair (1800), Subramanyan uses symbolic flowers to paint a sensual performance. His is a theatre of the bizarre. In the work a goat nestles into the woman's oddly Futurist torso, attempting to suckle at her breast. K.G. Subramanyan relished the fantastical licence this Bengali style gave him.

As he explained in a lecture to an audience at the Festival of India held at the Barbican Art Gallery, 1982, 'The exposure to the fantasy, innovation and earthiness of the non-professional revitalised the professional and saved it from preciousness.'

Subramanyan's assimilation of styles and absorption of Indian heritage had a profound influence on other Baroda luminaries.

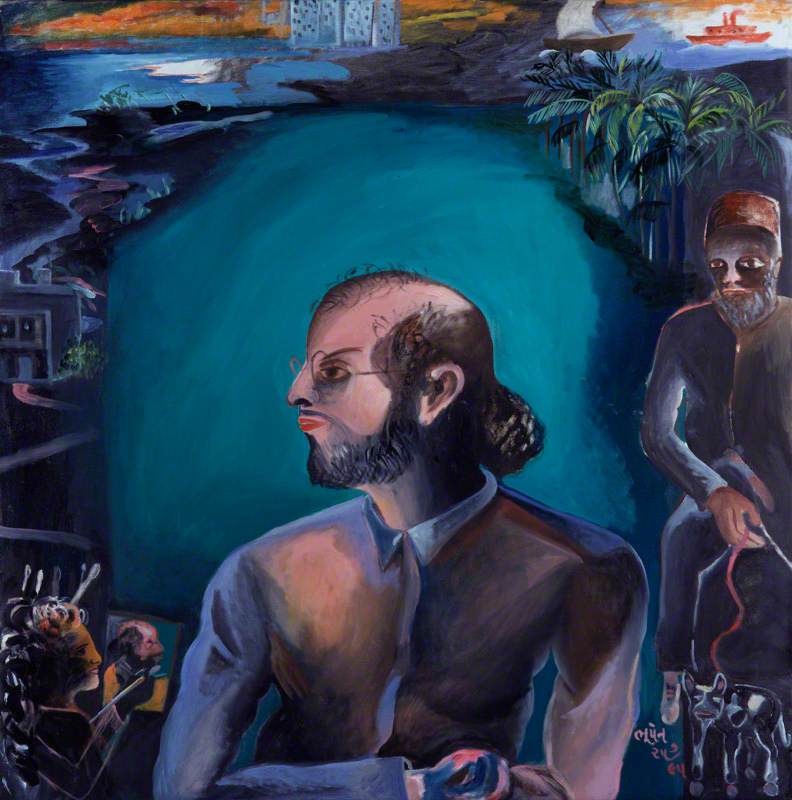

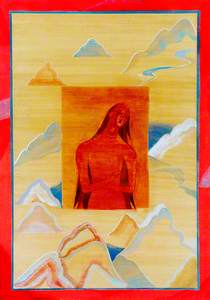

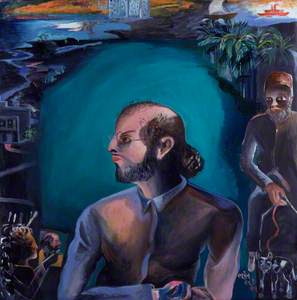

Bhupen Khakhar and Gulammohammed Sheikh deftly blended aesthetics, idiosyncratically referencing miniature painting and modernist genres. In a seminal move, the artists invested their canvases with the fragility of personal experience and their politics of place.

It was a show, 'A Place for People' held in Bombay and Delhi (1980–1981), which defined this new narrative figurative style. Curated by Geeta Kapur, the group exhibition inaugurated the 'Baroda School' group of artists.

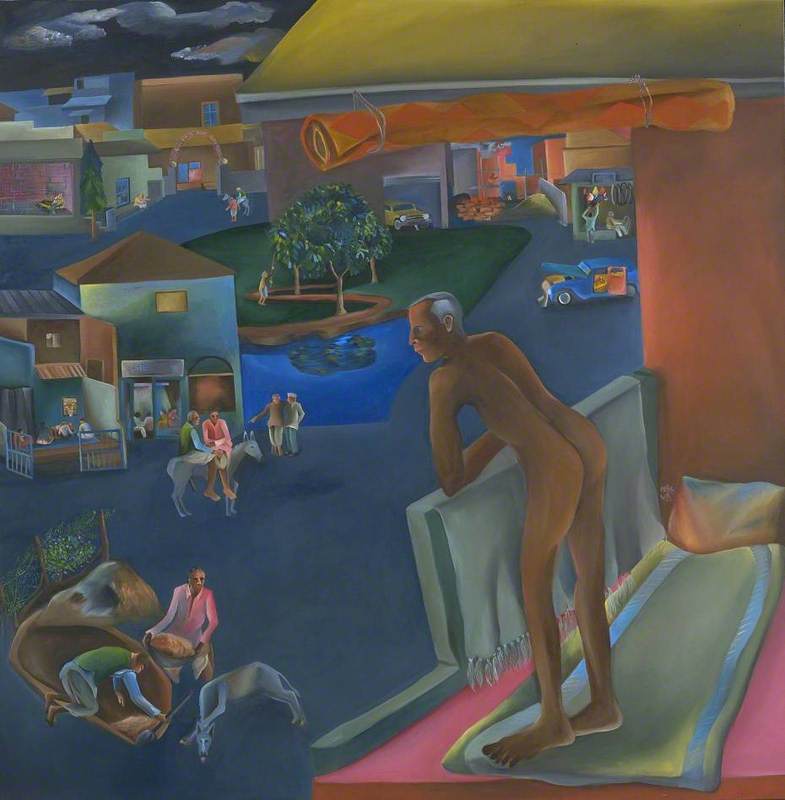

You Can't Please All (1981), Khakhar's kitschy yet sobering painting, a flattened transection of Indian life, was a highlight. Khakhar throws the personal together with the proverbial. Understood by critics as a revelation of his homosexuality, a lone naked man leans out on a balcony and takes in the scenes around him, which loosely reference Aesop's fable The Man, the Boy and the Donkey, a moral tale which concludes that you can never satisfy everyone.

The streets are, inconceivably for an Indian city, desolate and a dark sky weighs down on the coloured rooftops. The smattering of figures are seemingly unaware of their vulnerability.

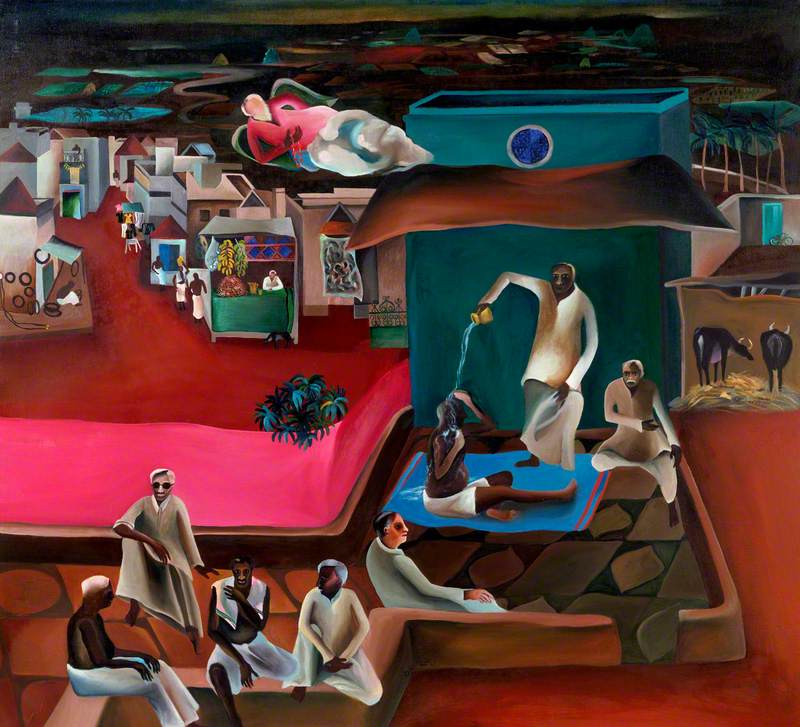

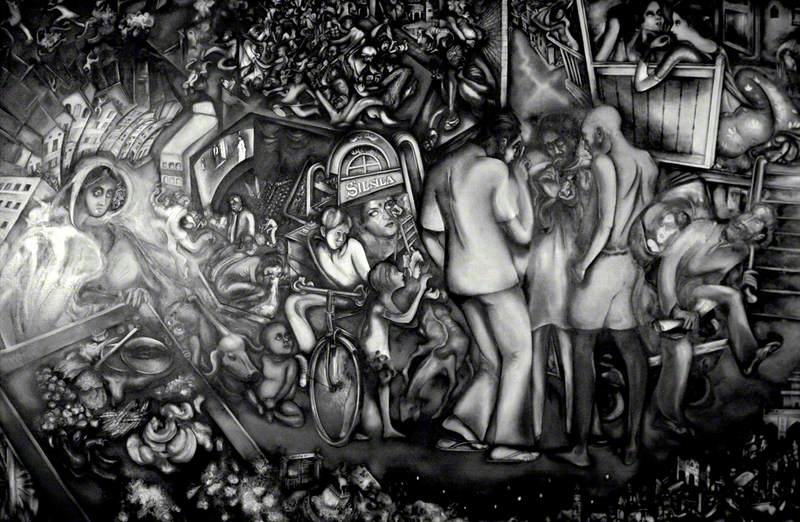

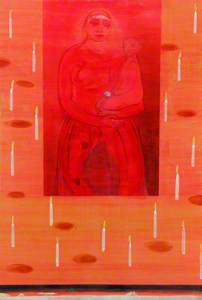

Sheikh's monochrome figures in City for Sale (1981–1984) writhe in a differently bleak street scene set in Baroda. Life is cheap here; bodies are bundled on top of each other, children and animals are compressed together, homes buckle and bend. The city is vicious and unsparing.

The grim scenes recount the communal riots which besieged Baroda in 1969.

This allusion to reality is blended with mythology. In the centre of this work painted in the early 1980s, a billboard brandishing a poster of Silsila, a popular film released in 1981, is being worked on. A man teeters on a ladder completing the image of the film's main actress. Recalling portrait rituals associated with the Santal tribes, he paints in the pupil of the eye – the aspect of the face completed only at death.

Dense in their creative references, these works speak to Baroda's comprehensive understanding of 'art'. The school was teeming with talent and its reputation persists.

Nilima Sheikh and Tanya Goel are part of the lineage of this great art school. With the model of the Fine Art Fair being rejuvenated after a nine-year hiatus, it is plain that Subramanyan's legacy remains as intact as ever.

Cleo Roberts, art historian