The incense I burn at home is made by Satya – it says so in big, red, type on a patterned box that claims to contain 'celestial' scent. My agarbatti sticks by Satya are hand rolled in the traditional 'Flora' technique in India: a masala (spice-blend) massaged into a gum and skewered by bamboo, then dipped into a perfumed powder.

Satya claims that 'jobs at [their] establishment frequently pass hands from grandmothers to mothers to daughters'. Those hands are crucial conduits for transference of heart energy, just as a writer might hold a pen, or an artist might hold charcoal. When this process is industrialised, like in the 'charcoal' method of making incense – which imports manufactured 'blanks' from China that are shot through churned dust – the pulse of the artisan is erased. Communities of practice diminish along with haptic, generational memory. Unlike the repetition of industry, craft requires a reverence of material and remembrance of the many links in its long, transformative chain.

An agarbatti's skewer is wet wood bamboo whose give is more like wind than tree. The charcoal gum dreams of a future orange glow as it burns, and the starry magnolia of the champak tree that is blended into a masala will remain just a whisper to the perfumes constellated in smoke through my room.

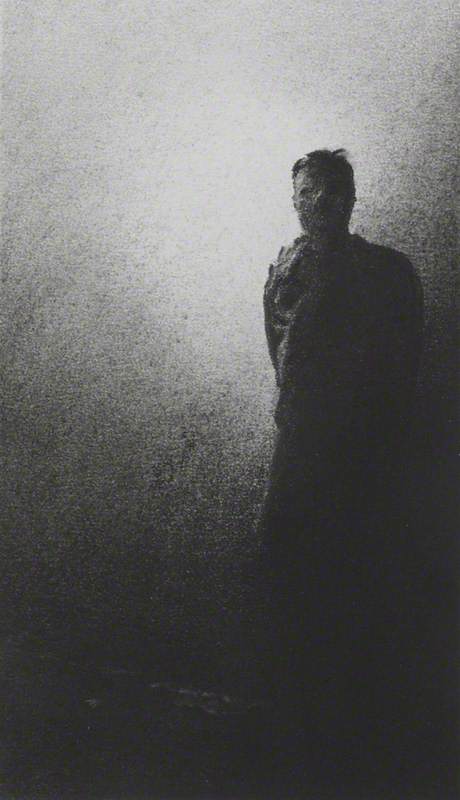

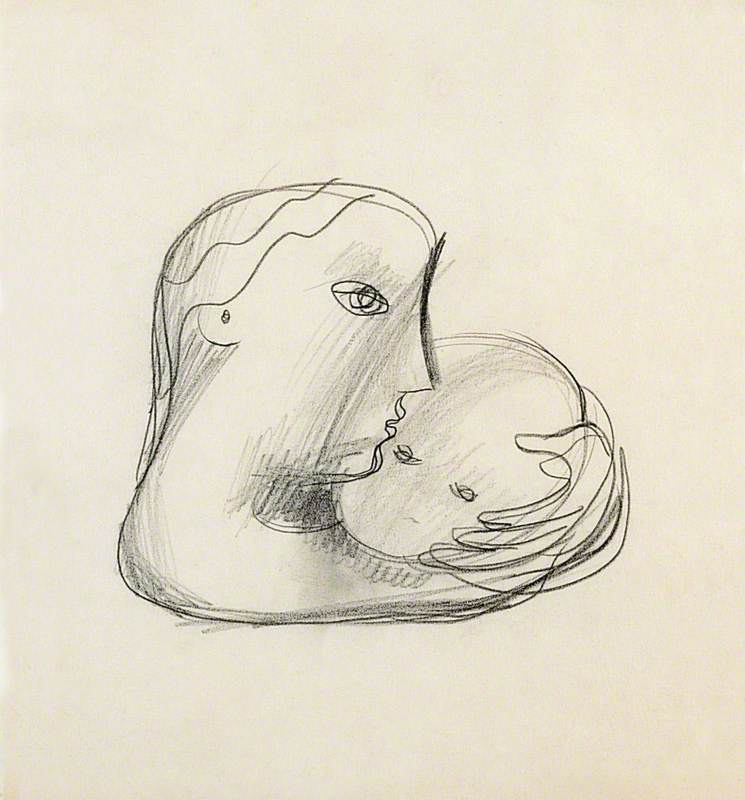

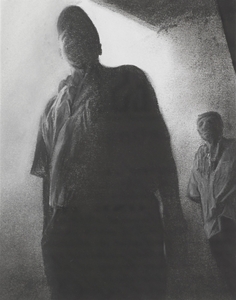

Alan Kilpatrick takes this world as his subject in his charcoal 'Incense Workers' series. In the first drawing in the series, the space itself already seems to be vanishing, burning up. Tilt your head to the right and the stacked rolls of bamboo become wavering licks of flame. Without the sequence's title, we would never have guessed that we were looking at an incense worker in India. We, the viewers, become detectives in a space where light is constituted by negative space. With one hand on the warehouse door, the worker who wields such strange light might as well be the artist moving into the space he has drawn.

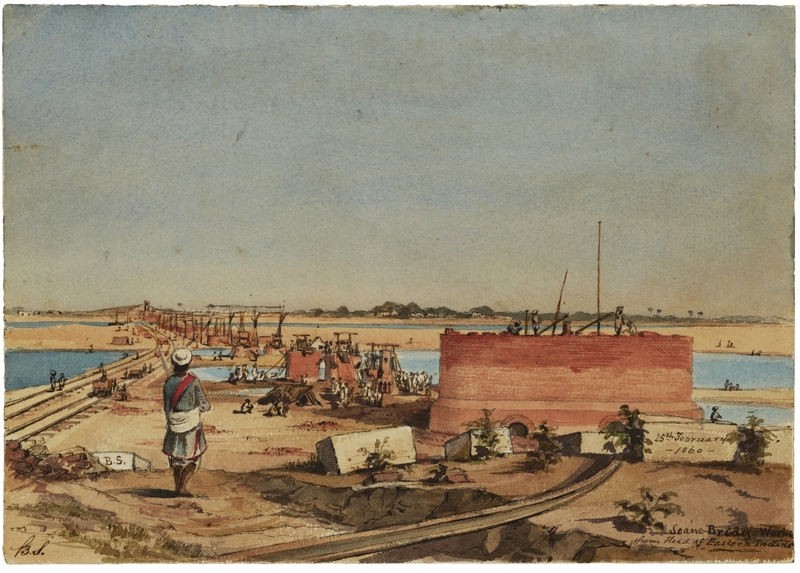

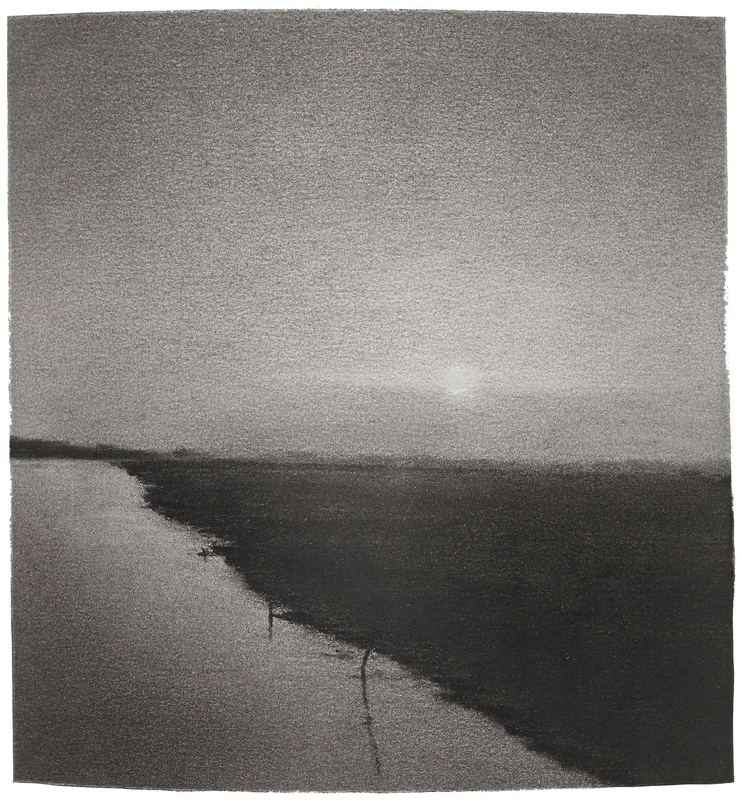

Where the Brahamaputra Meets the Clyde

(series no. 3) 2003

Alan Kilpatrick (b.1963)

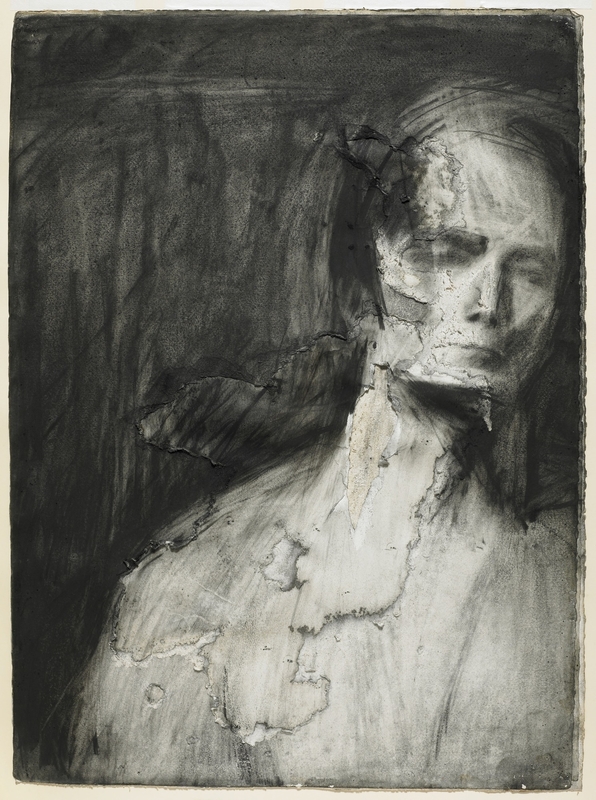

Born in Assam before moving to Edinburgh in 1991, Kilpatrick's artistic practice explores the legacies of craft and labour in post-colonial India. His charcoal drawings address the liminality of space and material. Rub your thumb along charcoal and you won't map a clear line – in fact just the opposite: pull it far enough and it will disappear completely into blended shadow. Kilpatrick's 2003 series 'Where the Brahmaputra Meets the Clyde' discovers in this non-specificity an eternal environment, one in which the tide dappling on the firths of Edinburgh is the same as the one on the banks of Assam. The 'Incense Workers' series complicates these trans-geographic aims by engaging more directly in the political complexity of contemporary India as well as wrestling with the implications of the medium of charcoal. Once it has burned from blue aromas into its crushed and ochre husk, the material of incense is fundamentally the same as the charcoal that Kilpatrick works with.

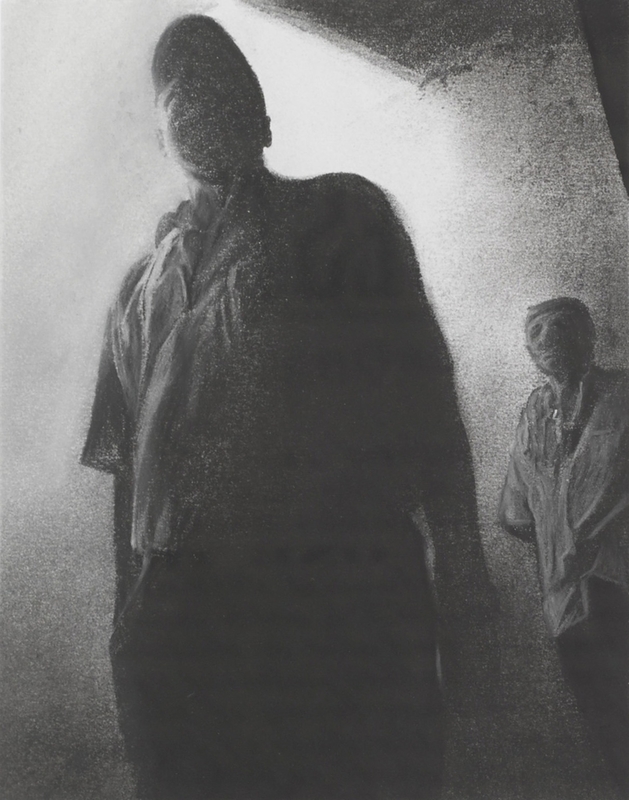

When Kilpatrick confronts me with the workers behind the incense I buy, I am greeted by dissolute chimeras emerging like smoke with blind sockets for eyes. Lit in sharp contrast between black and white, I am reminded of dream-corridors and the backrooms of the imagination. The strangeness of these scenes weaponises the eye, and the charcoal suddenly takes on the residue of gunpowder, which is perhaps the pervasive scent of Britain's relationship with India.

The threshold between seemingly innocent visions of an Indian paradise and the bloody plundering of its shores is thinner than you think, and the great haul of Indian loot piled in British museums and paraded on the heads of our monarchs was not willingly given. Instinctual, and imaginary exoticisation of distant shores engages only the naive senses (smell, taste) to briefly illuminate an Indian river-world, bright and bending, with glinting bikes and golden domes, totally disregarding the multifaceted truth of human experience. In short, this exoticisation is a process of othering, and othering is a process of violence.

Kilpatrick rejects a traditional British visual language of exotic othering in these works. Whilst we, the viewer, are restrained from our impulse to ogle a vivid, imaginary India, we are also divorced from any detailing of truth. Information appears in distorting half-light, glitching away from the mind's hunger for clarity. Kilpatrick's charcoal seems to contain within it the multivalence of Indian identity.

India's current political landscape grapples with the exceptional diversity of cultures within its borders. The 'New India' proposed by Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the Bharatiya Janata Party intends to usher in industrial and mechanical efficiency, gradually eradicating the artisanal inheritance that has been integral to the process of making incense and other hand-crafted products across generations.

Caste lines are drawn and extended between artist and artisan, craftsman and industry, consumer and creator. Where one falls on either side of the line mostly has to do with wealth and the legacies of power. Whilst stacks of incense line the shelves of British shops for a couple of pounds a box, we hang art like that of Kilpatrick's on the walls of castles in Edinburgh. The colour and origin of the hands that made these things determines their value.

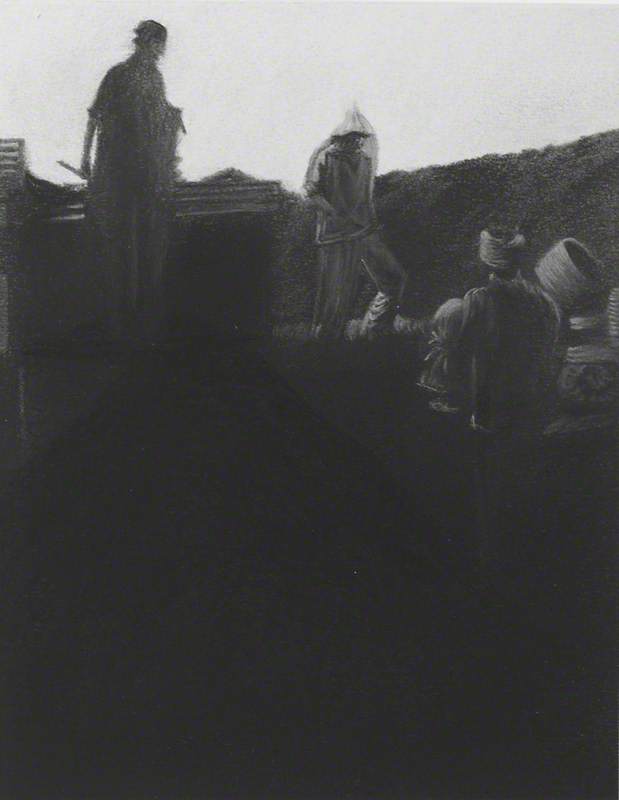

Drawing's inherent tension (why this line and not another line) is beautifully blurred by charcoal's intimacy with erasure. It is a material made from the rebirth of scorched matter that, without emulsifier, walks carbon's tightrope into decay. The third and fifth drawings of Kilpatrick's sequence depict the same scene at different distances. I feel urged to look closer but, when I do, even less becomes clear. The figures morph into a gargoyle monument to craft whilst simultaneously disappearing fully into labour. The final drawing shows a swath of such solid black your finger would crumble it away in blocks, leading deeper into nothingness. Paradoxically, this is where the oily source of incense runs, and the workers emerge directly from it without meeting the viewer's gaze.

The distance between my purchasing of the incense sticks in Britain and the hands that made them in India feels fathomless, and the webbed legacy of commerce and bloodshed that sustains this disconnect is drawn into an inky, nebulous mass. Distinction jars between the products that I can afford and the art that I cannot. But far away from the incense workers, when I welcome you into my home, I have already made space for you. You can sense it in the air. And as you settle in, you become aware of your own presence in a chamber drawn by sweet smoke, draped corner to corner like canvas. At the tip of your nose, it counts your breath for you, and you feel unburdened. Like these drawings, it was handmade for us to use how we wish, and is only fleeting compared to the materials it is made from.

Caleb Carter, writer, poet and researcher

This content was funded by the Bridget Riley Art Foundation

Further reading

William Dalrymple and Anita Anand, Empire (podcast), 2022

David Howes, Empire of the Senses: The Sensual Cultural Reader, Berg, 2004

Edward Said, Orientalism, originally published in 1978 by Pantheon Books