'William Gillies: Modernism and Nation' will feature oil paintings, drawings and associated photographs, archives and objects from the Academician's entire career. The exhibition will show at the Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh from 9th December 2023 to 28th January 2024, and in parallel at the John Gray Centre in Haddington, before touring around Scotland in 2024 and 2025.

Andrew McPherson has researched the life, times and works of William Gillies – one of Scotland's most important twentieth-century painters – for over 20 years. His forthcoming book, published to coincide with 'Modernism and Nation', provides new evidence to show that Gillies' art originates from his personal traumas and awareness of human fragility.

'Sir William Gillies is still highly underrated in Modern British terms' – The Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh

A key to Gillies' art is that he lived the first 50 years of his life beset by an existential crisis so great and so extended that it could destroy unless turned to creative advantage.

In 1918, and just turning 20 years of age, he returned thrice-injured from the Western Front to convalesce in a Paisley hospital. He was carrying other injuries too, from the madness and violence that had beset his childhood years. The war exacerbated the earlier traumas, for it also overturned the optimistic view of nature and humanity that underpinned the view of the artist he had learned from his Edwardian painting mentors. This old world was now a fiction exposed, ruled in truth by chaos and fate, and its sentimental pictures of itself were fictions too.

Image credit: Royal Scottish Academy

Gillies in the uniform of a private in the Scottish Rifles

1917, photograph by an unknown artist. Part of the RSA Sir William Gillies Bequest, 1973

He began again in 1919 by trying to suppress his past and embracing instead the camaraderie of a college in which a group of young veterans were sceptical of all manifestos, traditional or modernist. They were just happy to be alive.

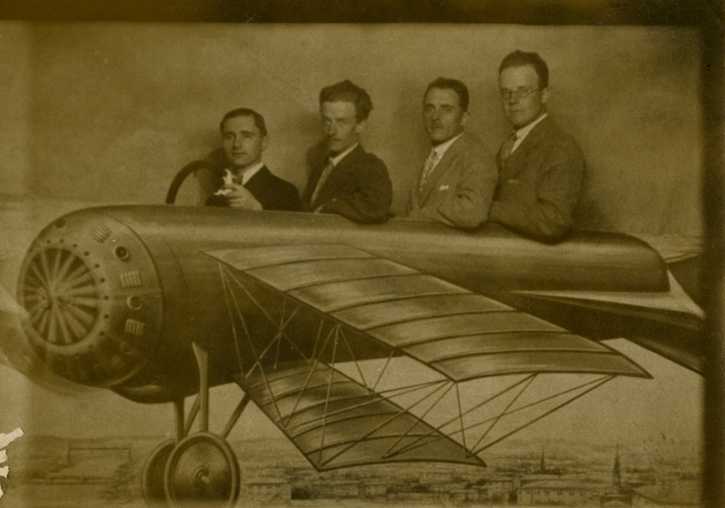

Image credit: Royal Scottish Academy

Gillies and companions in a studio 'bi-plane'

photograph by an unknown artist. Part of the RSA Sir William Gillies Bequest, 1973

Gillies' art emerges from his lifetime effort to acknowledge these two extremes in an unsentimental expression of the human condition – on the one hand, the capacity for joy and transcendence, on the other, the fleeting fragility of life and the arbitrary injustice of its outcomes.

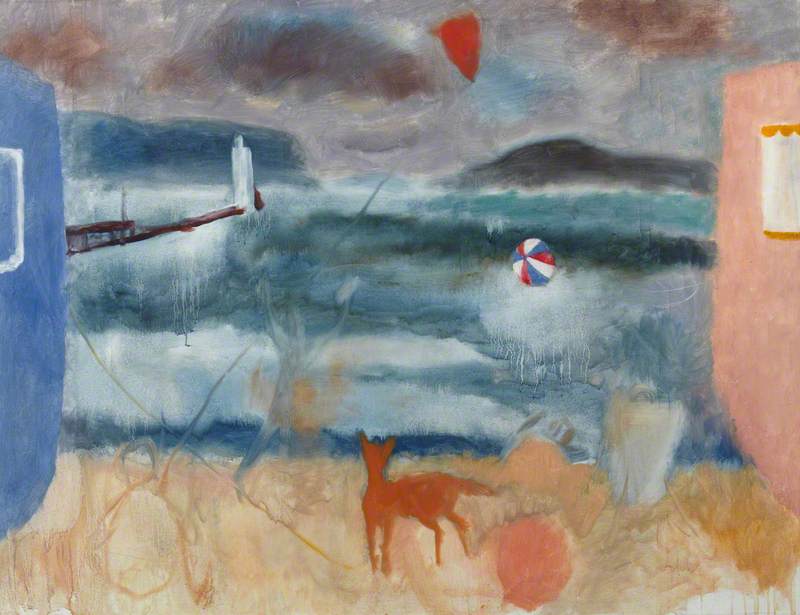

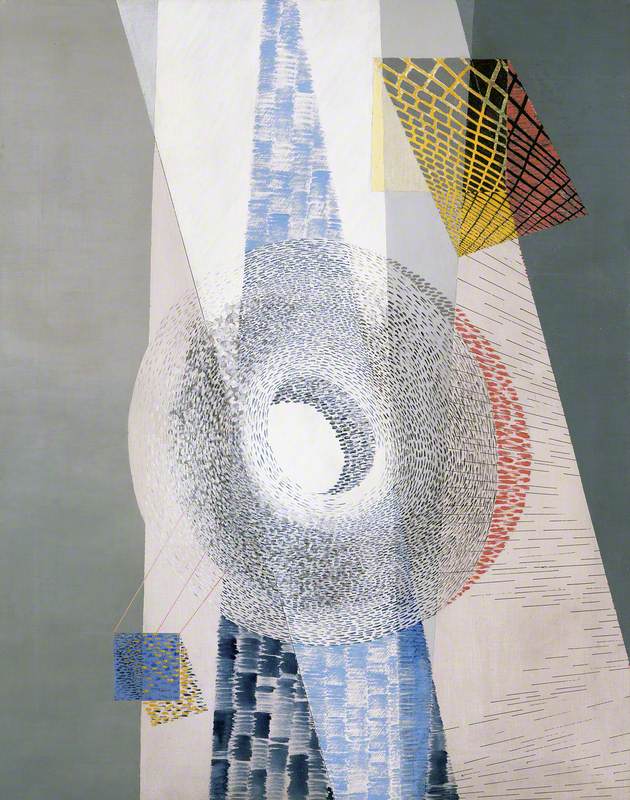

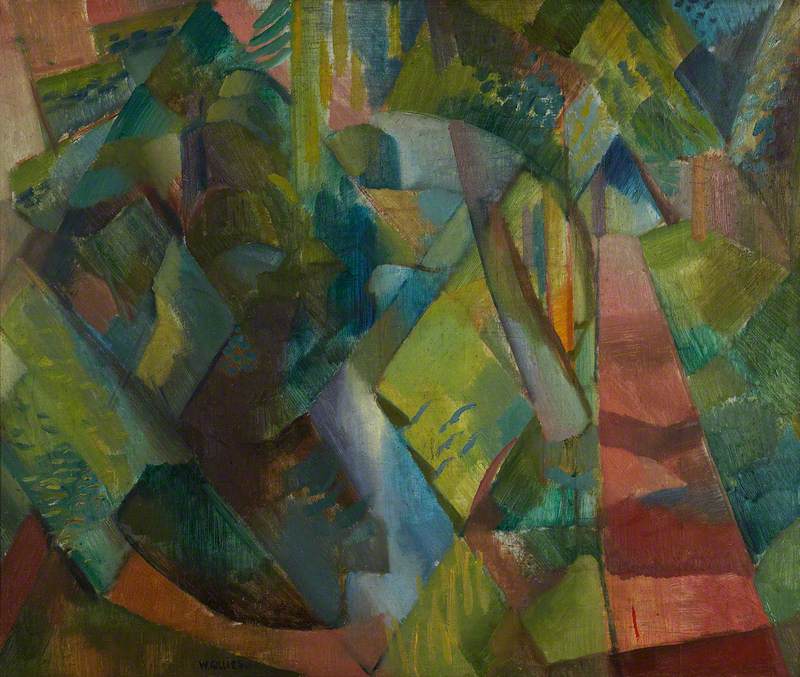

© Royal Scottish Academy / Bridgeman Images. Image credit: Royal Scottish Academy of Art & Architecture

William George Gillies (1898–1973)

Royal Scottish Academy of Art & ArchitectureHis early attempts at suppression failed him. A pulse of untimely deaths, suicides and suffering among those close to him extended the initial traumas of war and childhood into and beyond the Second World War, bending time back on itself. The past became a continuous present he could neither escape nor deny. For years, he could not know whether the genetic inheritance that led to the deaths of his younger sister and one of his closest colleagues would take him too. But he found in Cubism a Charter of Liberty. Munch showed him that he could paint better by painting his own life. Klee showed him how perceptions of the real are a creative act and how the artwork transcends the real.

© Royal Scottish Academy / Bridgeman Images. Image credit: Royal Scottish Academy of Art & Architecture

Trees on the Tyne, Haddington c.1924

William George Gillies (1898–1973)

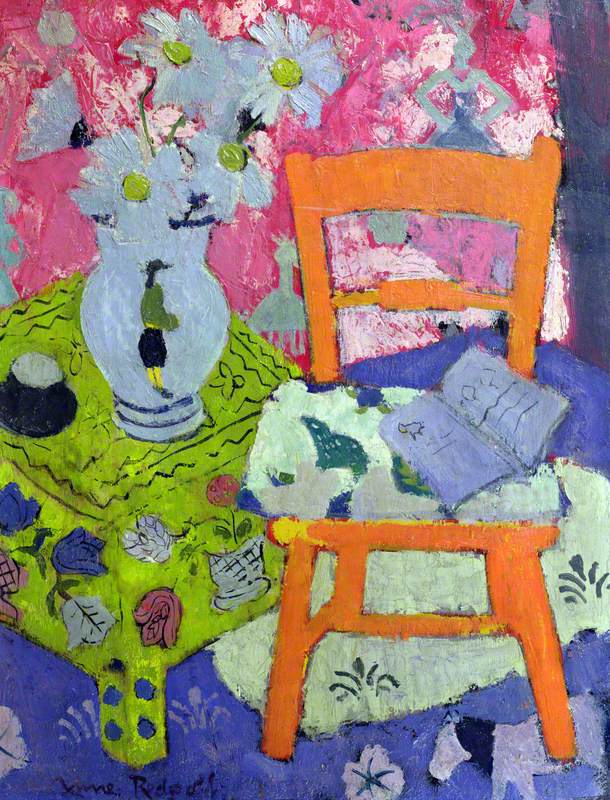

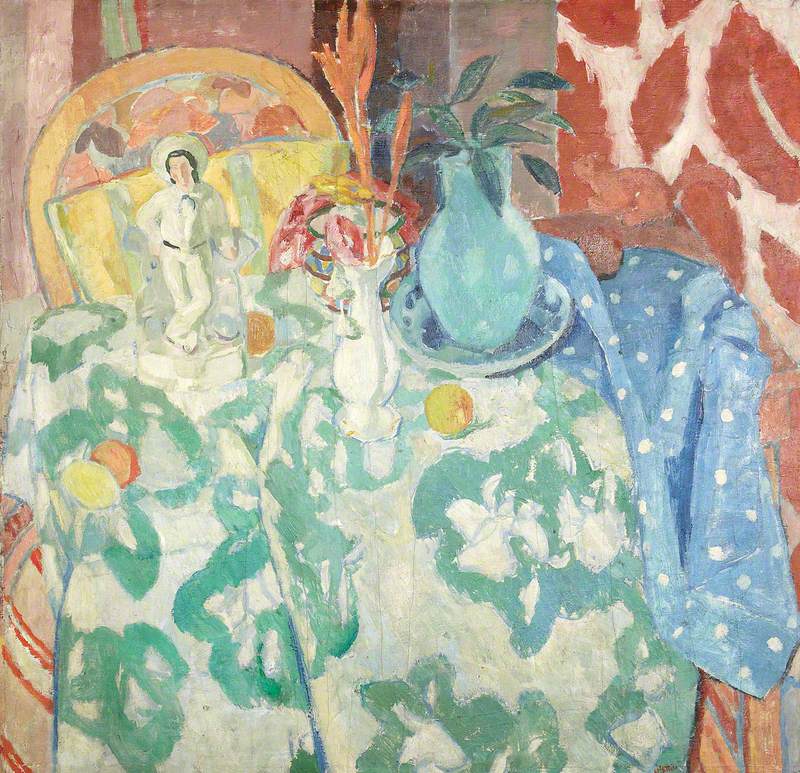

Royal Scottish Academy of Art & ArchitectureIn the 1930s, Gillies' confessional portraits of his family began a recuperative liberation that drew on these early exemplars. It continued in the still-life oils of the following 15 years and then in the oil landscapes of the second half of the 1950s – a world remade by owning the self to the world and the world in the self.

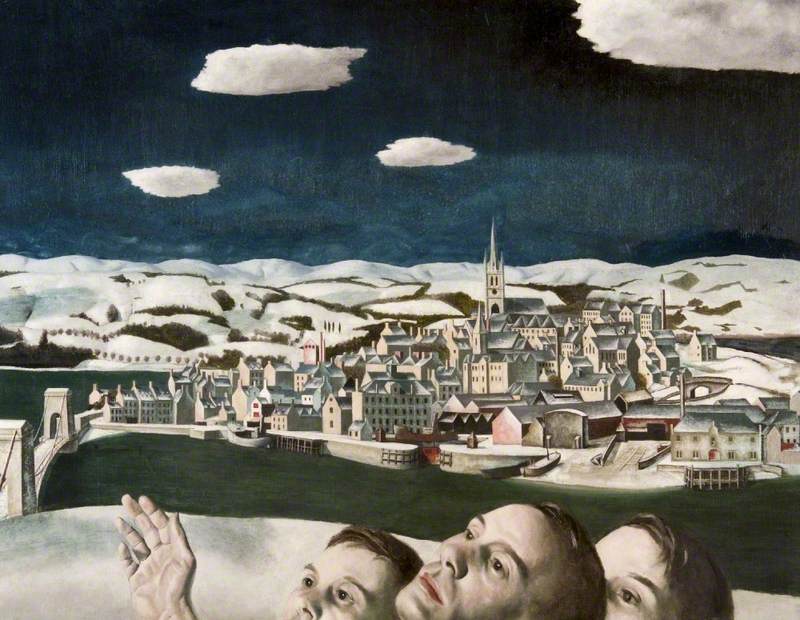

© Royal Scottish Academy / Bridgeman Images. Image credit: Museums & Galleries Edinburgh – City of Edinburgh Council

William George Gillies (1898–1973)

Museums & Galleries Edinburgh – City of Edinburgh CouncilThe cascade of watercolour drawings of landscape that followed the Second World War also has origins in the First – not just in the contrast they present with the wasteland of the trenches, but in a distinctive, veteran, understanding of perception as well. As the daily Stand to Arms sounded, Gillies and his fellow privates anxiously scanned the grey of dawn for colour and light that cognition could interpret as the forms of reality.

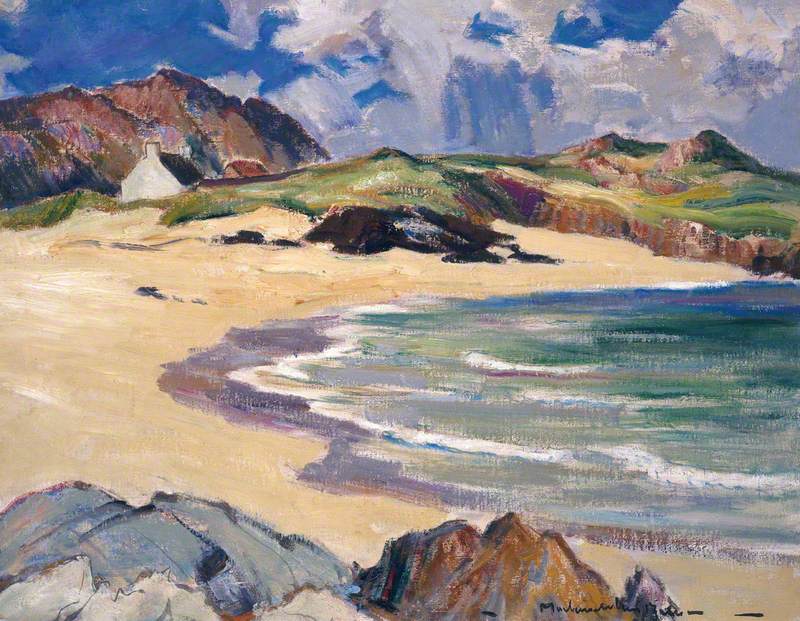

© Royal Scottish Academy / Bridgeman Images. Image credit: Royal Scottish Academy of Art & Architecture

William George Gillies (1898–1973)

Royal Scottish Academy of Art & ArchitectureSo, it was the infantryman in Gillies that grasped what was at issue between Klee, Kandinsky and Delaunay at that key moment in 1913, when their exploration of figuration, colour and form first admitted the practice of pure, non-figurative abstraction. And it was the watercolourist in Gillies who could abstract form out of colour suspended in water, and float retinal experience into that abstraction. Witness in particular the fluid expressionist landscapes of the inter-war period.

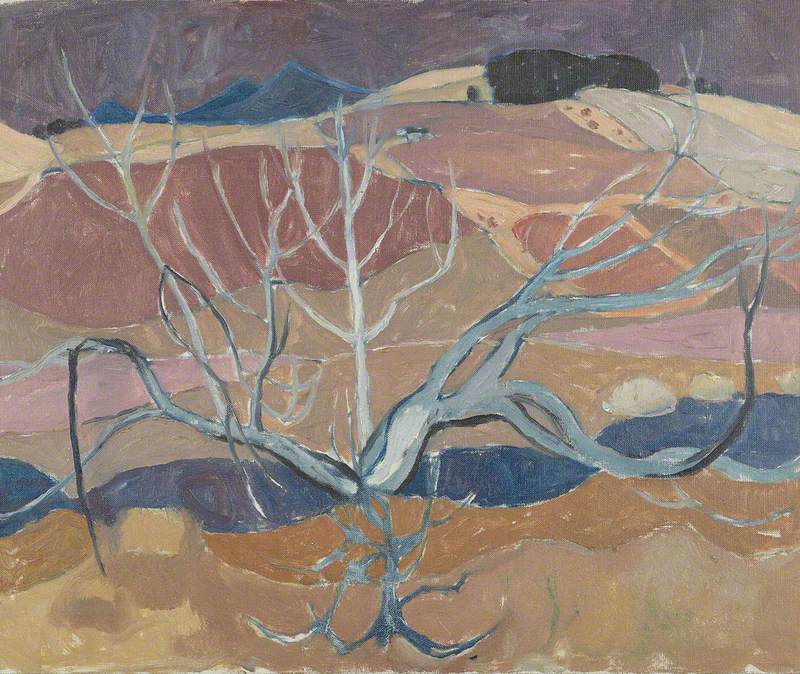

© Royal Scottish Academy / Bridgeman Images. Image credit: Royal Scottish Academy of Art & Architecture

The Red House, Durisdeer c.1934

William George Gillies (1898–1973)

Royal Scottish Academy of Art & Architecture

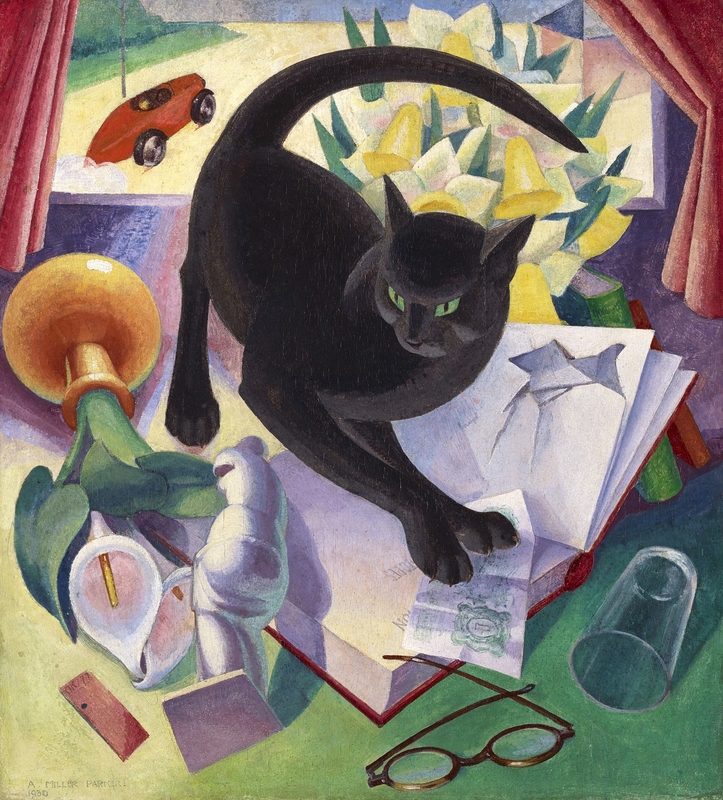

© the artist's estate. Image credit: courtesy of a private collection

Winter Landscape

c.1933, oil on canvas by William George Gillies (1898–1973). Private collection

The post-1945 wash drawings too conveyed, in the words of David Baxandall (broadcast on Arts Review, 1963), a 'curious exaltation' and could act on feelings 'more deeply than we can explain'. For Klee, exaltation lay in the way the artwork replicated the invisible forces and emergent forms of Creation itself, a portal from the mundane world to the forces that animate it.

Baxandall was Director of the National Galleries of Scotland from 1952 to 1970, a personal friend of Ben Nicholson and a connoisseur of British modernism. The National Galleries of Scotland viewed Gillies as a countryman and topographer who was indifferent to the modern movement and had no place in a gallery of modern art. Gillies' supporters argued that it was precisely because he was a countryman that he belonged in the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art. The Gallery was finally opened in 1960 after an indigenous campaign as old as the century.

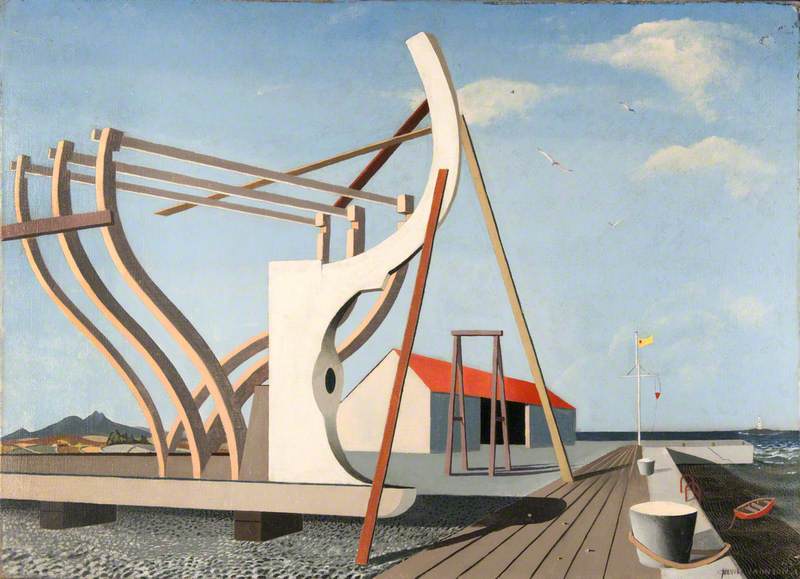

© Royal Scottish Academy / Bridgeman Images. Image credit: Royal Scottish Academy of Art & Architecture

Between Raeshaw and Carcant on Heriot Water c.1968

William George Gillies (1898–1973)

Royal Scottish Academy of Art & ArchitectureWilliam Gillies: Modernism and Nation in British Art argues that both positions misunderstood the man and his work. The real William Gillies has been hidden, of his own volition, behind stereotypes of culture and place engendered by historic struggles over the control of Scotland's image and image-making. England, Scotland and the countryside, Edinburgh, Haddington and Kirriemuir, religion, the Kailyard and sexuality – the influence of all of these on his life has to be rethought or acknowledged for the first time. This done, one can see more clearly in the works themselves how the real William Gillies has also been obscured by the very modesty that enabled his unique realisation of the freedoms of the modernist epoch.

© Royal Scottish Academy / Bridgeman Images. Image credit: Royal Scottish Academy of Art & Architecture

Two Jugs, Flowers and Conch Shell c.1952

William George Gillies (1898–1973)

Royal Scottish Academy of Art & ArchitectureAndrew McPherson, Professor Emeritus in Sociology at the University of Edinburgh

William Gillies: Modernism and Nation in British Art by Andrew McPherson will be published by Edinburgh University Press, supported by the RSA, in October 2023. The book is available to pre-order from the Edinburgh University Press website

The exhibition 'William Gillies: Modernism and Nation' will tour around Scotland in 2024 and 2025 to Rozelle House in Ayr, Hawick Museum, Perth Art Gallery, Taigh Chearsabhagh in North Uist, Pier Arts Centre in Stromness, Inverness Art Gallery, Kirkcudbright Galleries and Gracefield Arts Centre