I've long loved trees and walking among them. Each day I make sure to spend at least some time appreciating the beauty of trees; after all, it is trees that sustain our existence – without plants which turn sunlight into oxygen, we would not exist. Artists too have had a long love affair with trees and delving into the abundance of arboreal art is fascinating.

Trees stretch their branches throughout many paintings, from street trees to copses to parks to forests and rainforests, and trees are depicted in all stages of their growth, all around the world, and in their many varieties. We see their branches reaching high into the sky and their roots stretching deep into the earth.

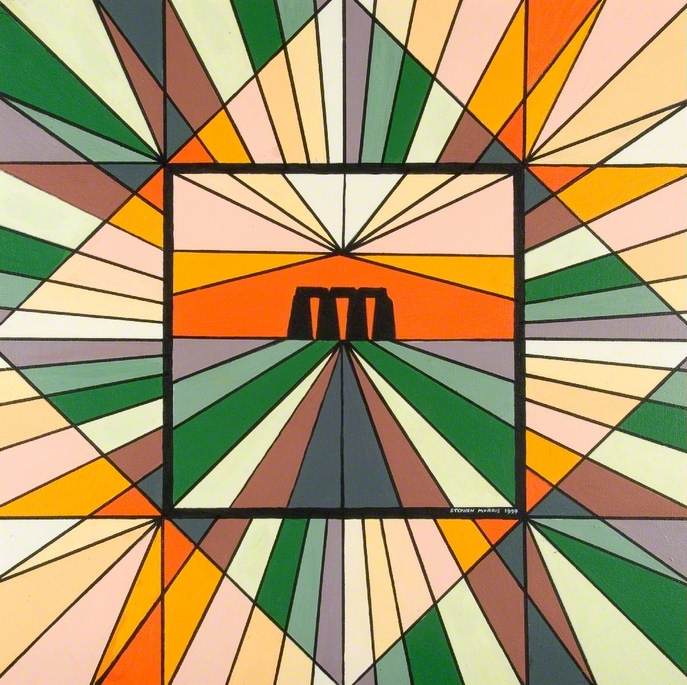

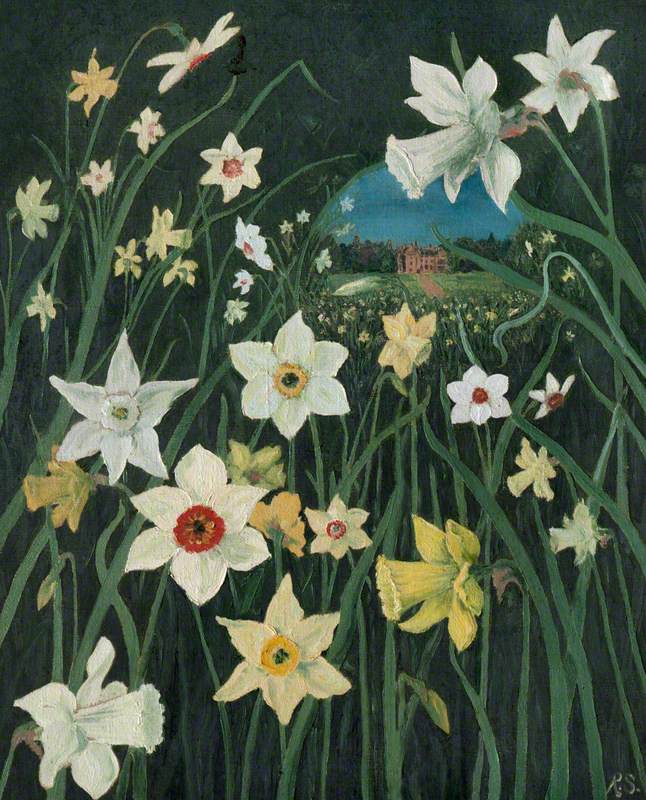

Trees have long been potent symbols in mythology, folklore and culture – the Tree of Life, the Sacred Tree, the Tree of Knowledge – forms of 'the world tree' also called the cosmic tree, thought to be the source of life at the centre of the world.

The Tree of Life symbolises the connection of all forms of creation (famous depictions include that of the Austrian artist Gustav Klimt in his painting The Tree of Life) while the Tree of Knowledge connects heaven and the underworld.

Image credit: The Board of Trustees of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

Foliage, Flowers and Fruit of a Tree Sacred to Krishna c.1878

Marianne North (1830–1890)

Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

Image credit: The Board of Trustees of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

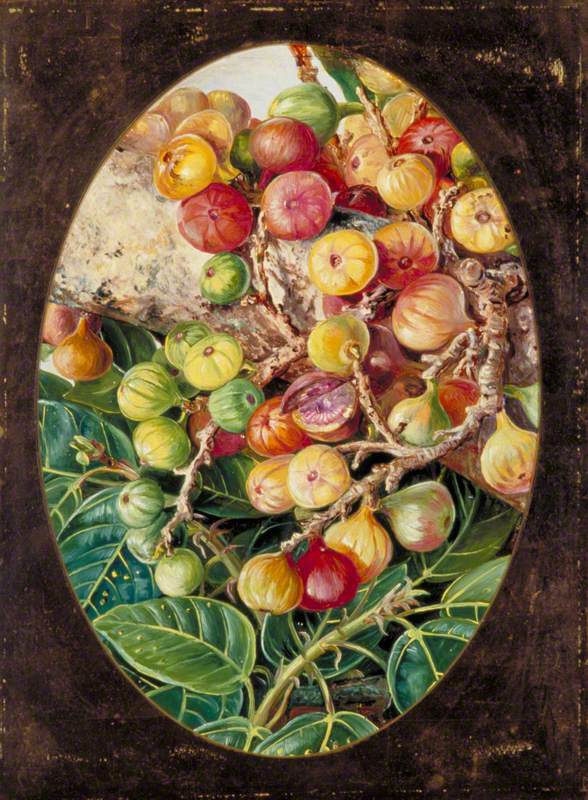

Foliage and Fruit of Fig Tree held Sacred by the Hindoos c.1878

Marianne North (1830–1890)

Royal Botanic Gardens, KewDepictions of 'sacred trees' include Foliage, Flowers and Fruit of a Tree Sacred to Krishna by Marianne North (1830–1890), as well as Foliage and Fruit of Fig Tree held Sacred by the Hindoos by the same artist.

On a beautiful winter's day a few months ago, I strolled past London plane trees lining the city, reaching their branches up into a clear blue sky, on the way to Tate Britain where I saw an exhibition of the work of Victorian artist Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898). He led the Pre-Raphaelite movement into new symbolist directions and his work interestingly draws on myths and legends. Art UK features his painting The Tree of Forgiveness, at the heart of which is an almond tree, and which is a dramatic reworking, in oil paint on canvas, of Phyllis and Demophoön in a style inspired by Michelangelo. In the myth, we see depicted Phyllis as she bursts out of the almond tree and embraces the lover who had abandoned her – a particularly powerful part of the painting is seeing her legs still inside the tree trunk.

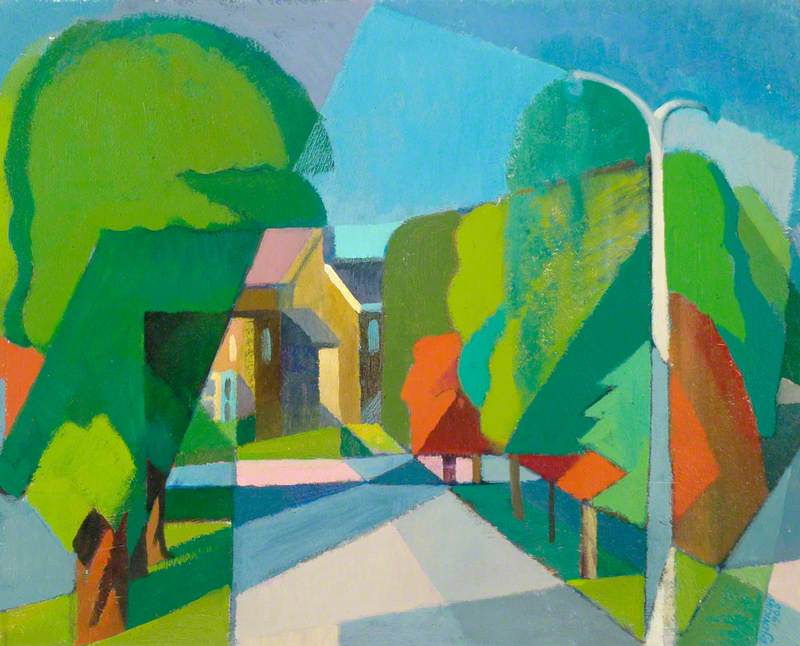

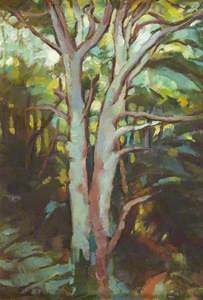

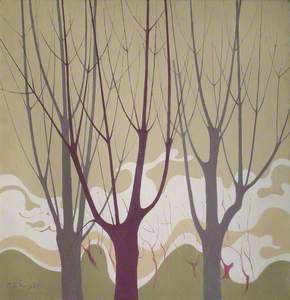

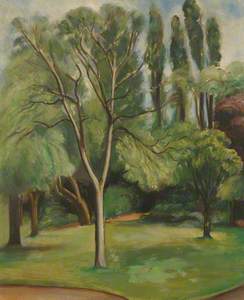

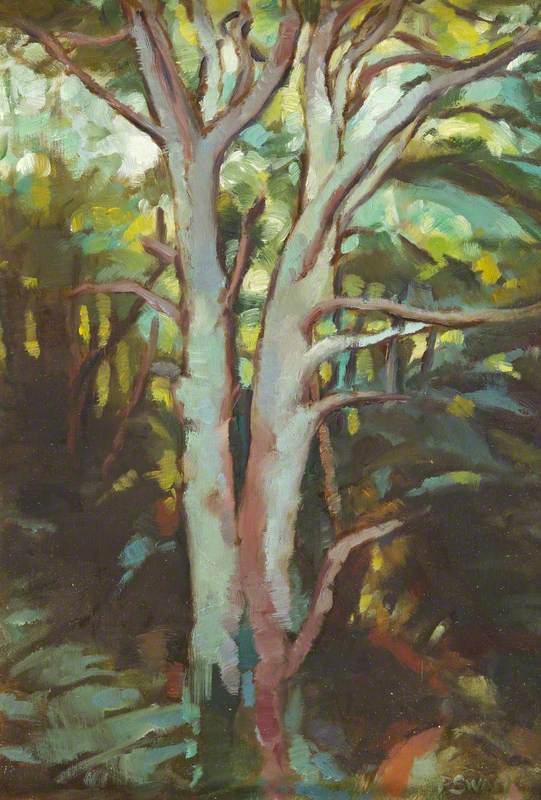

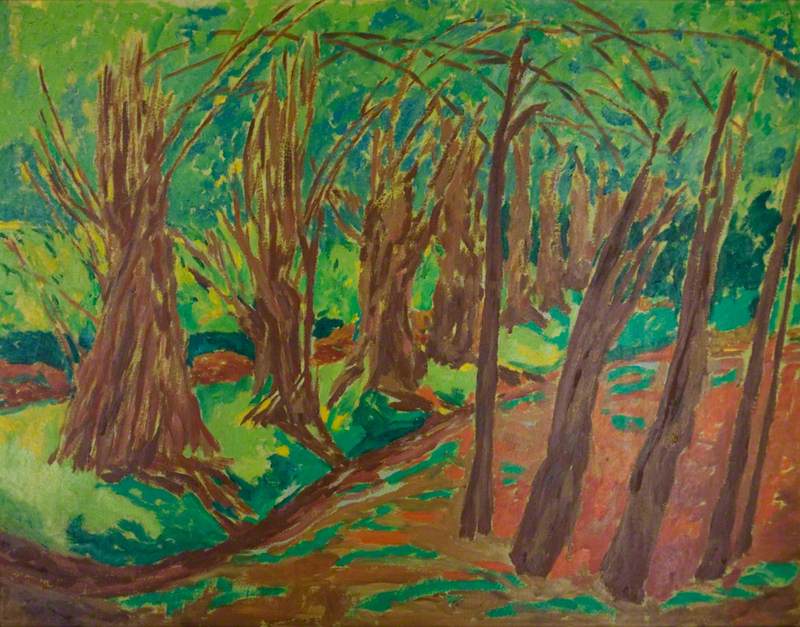

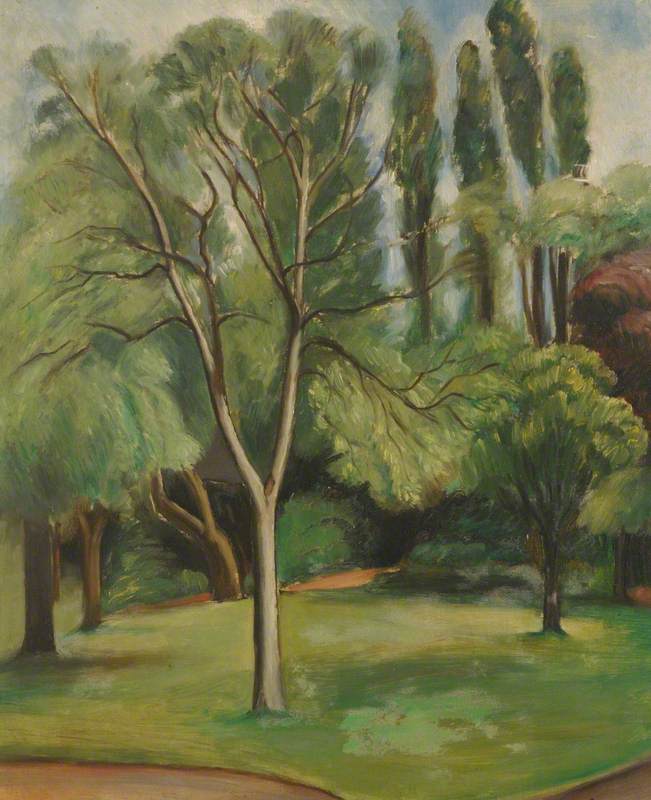

On days when it has been raining too ferociously to step outside, I have instead been gazing at arboreal art on Art UK. Paintings capture trees in all stages of their growth cycle, from lush foliage such as in Study of Trees by Bernard Meninsky (1891–1950) and Trees by Charles Napier Hemy (1841–1917) to the inky silhouettes of Winter Trees by John Woodward Lines (b.1938).

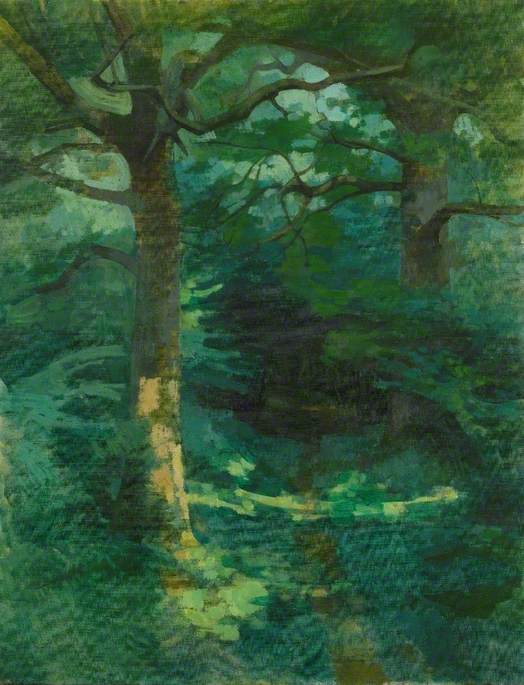

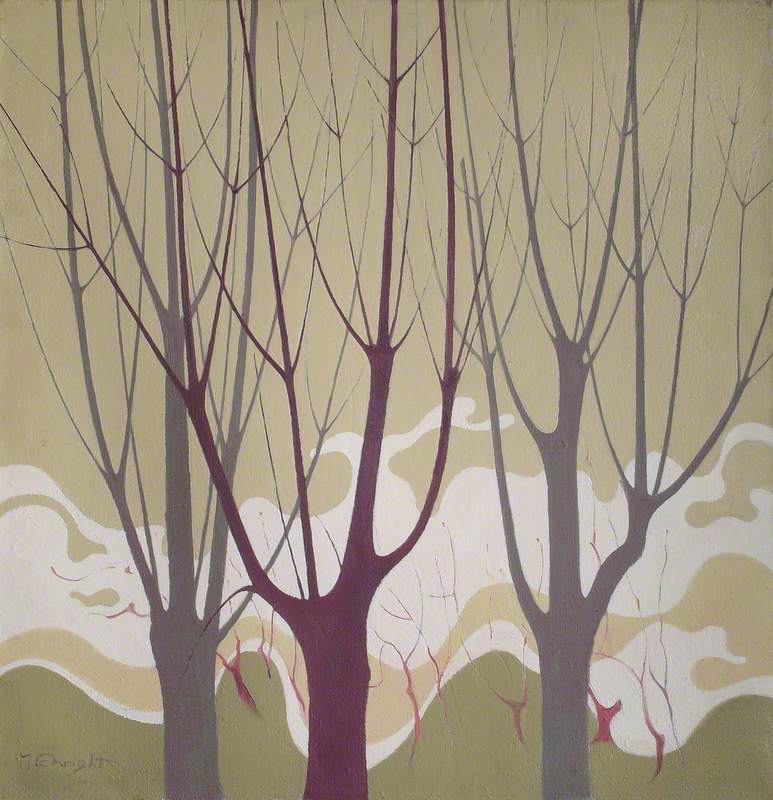

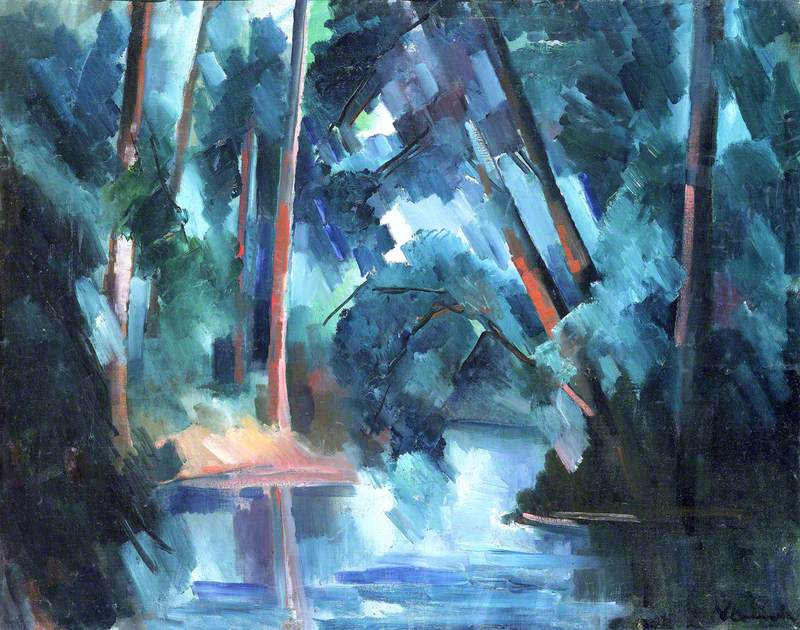

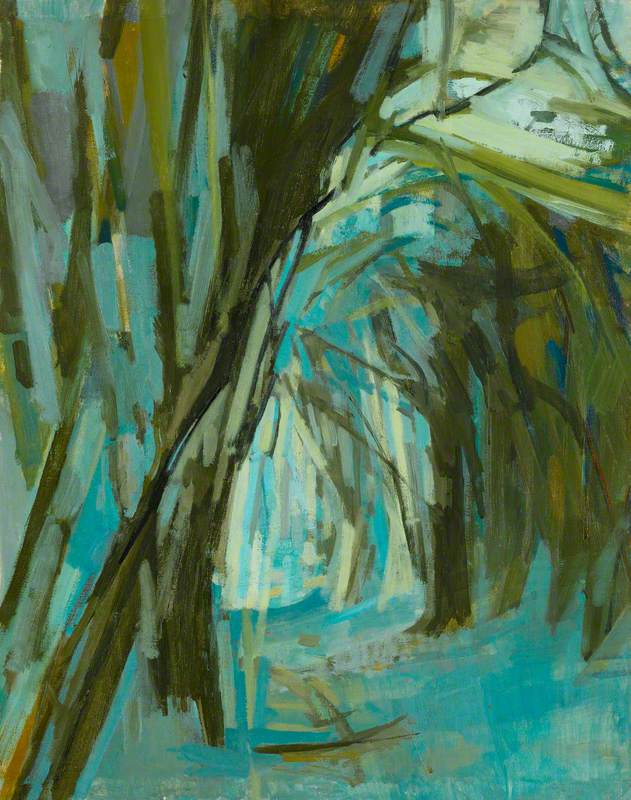

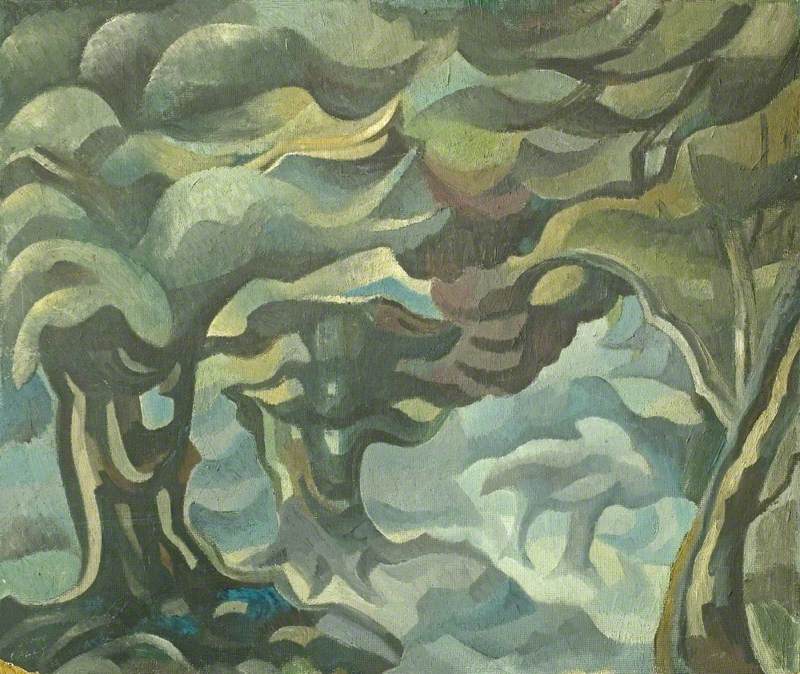

These stages of growth are also captured in abstract arboreal art, all titled Trees, from the wonderful juxtaposition of green and browns by Eardley Knollys (1902–1991) to the bony bare branches by Madeleine Enright (1920–2013) and the eerie painting by Benjamin Haughton (1865–1924). I also love the abstraction of blues and greens in a work by Maurice de Vlaminck (1876–1958).

© estate of Sir Lawrence Gowing. Image credit: Arts Council Collection, Southbank Centre, London

Cherry Copse at Stock Close, near Aldbourne 1951

Lawrence Gowing (1918–1991)

Arts Council Collection, Southbank CentreLooking at the copious amounts of copses in the archives I can imagine strolling through them, including Gifford's Copse and Cherry Copse at Stock Close, near Aldbourne by Lawrence Gowing (1918–1991).

Talbot Woods by Calvin W. Fryer (1871–1942) is awash with golden light and Woodland Scene by John Lally (1914–1994) is an abstract work excellently drawing out the shapes and patterns of trees.

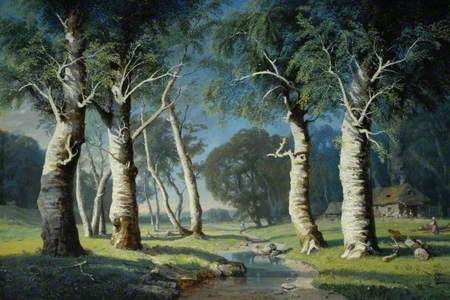

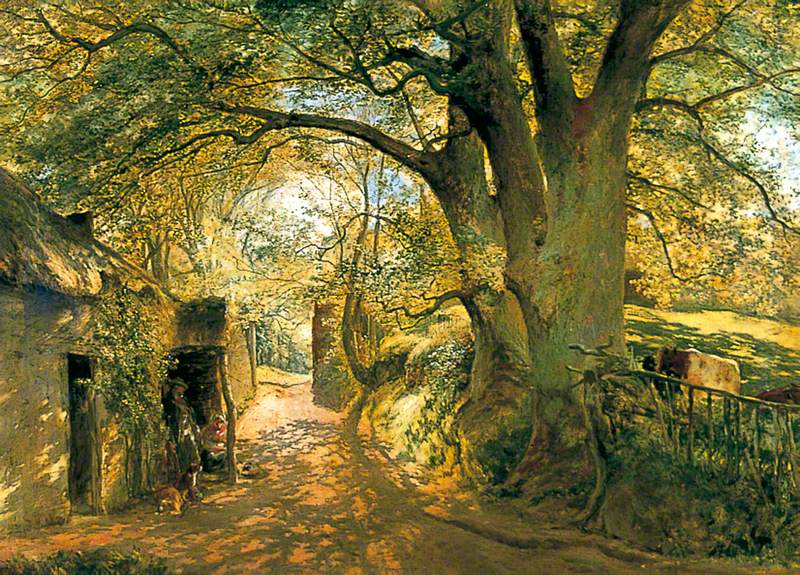

Entrance to Cadzow Forest by Samuel Bough (1822–1878) is also powerful with its wide, outstretched branches and shadows at the forest entrance.

© the artist. Image credit: Dorset County Hospital

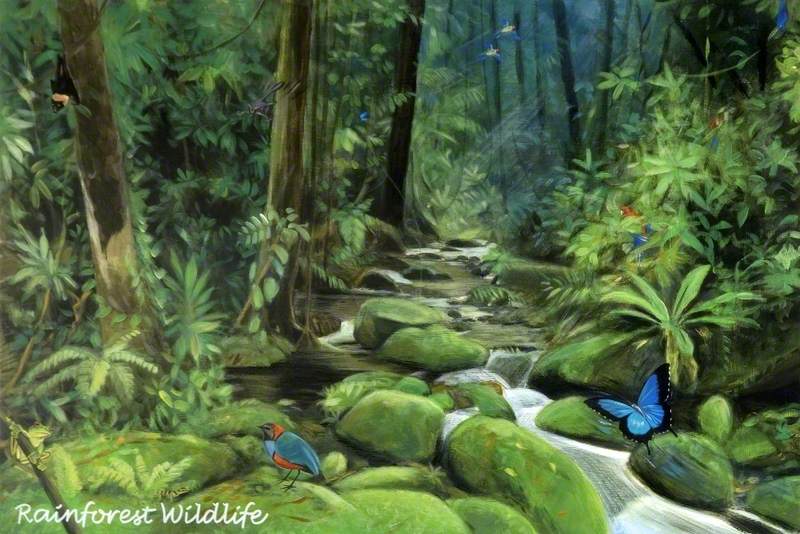

'Dreams of Australia' Series, Rainforest Wildlife 2003

Antonia Phillips (b.1966)

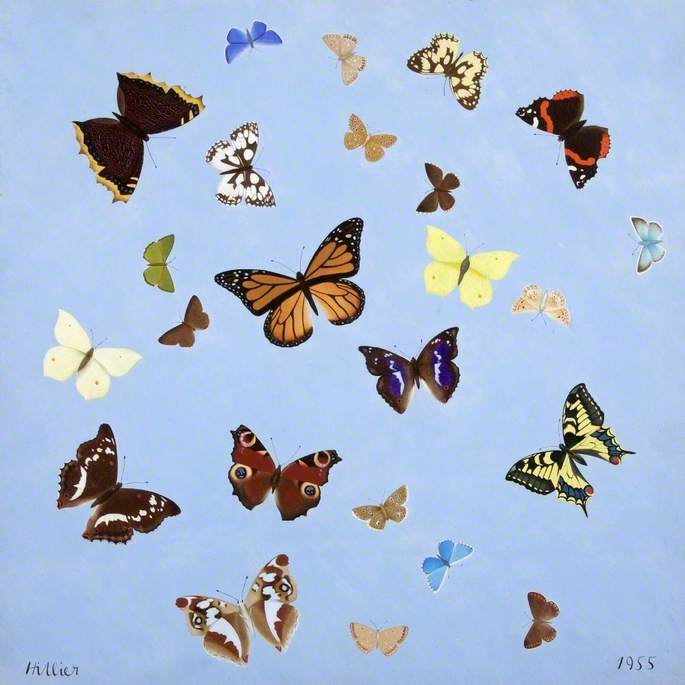

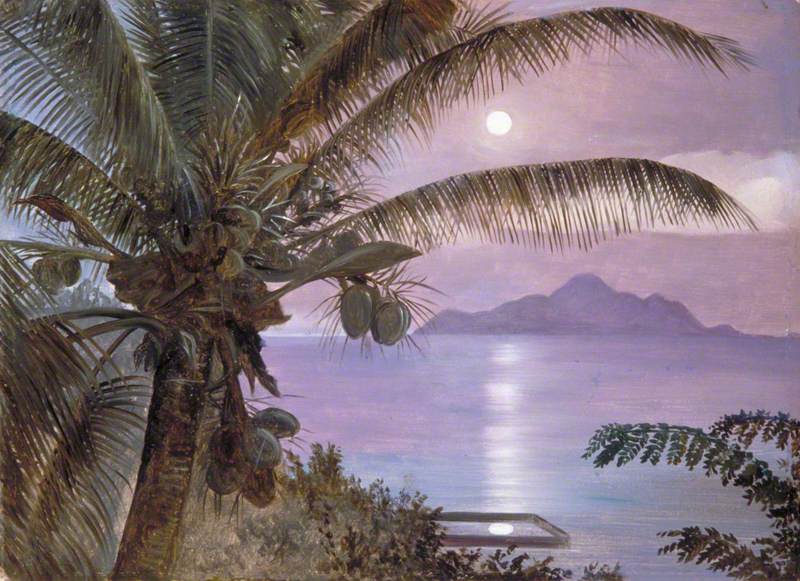

Dorset County HospitalLooking at the details in the rainforest depicted in ‘Dreams of Australia' Series, Rainforest Wildlife by Antonia Phillips, I am reminded of the vast diversity of life that trees sustain: beautiful birds and butterflies in this painting. Indeed, a single tree in a tropical rainforest can sustain up to 2,000 different species.

Image credit: Colchester and Ipswich Museums Service: Ipswich Borough Council Collection

R. Ellison

Colchester and Ipswich Museums Service: Ipswich Borough Council Collection

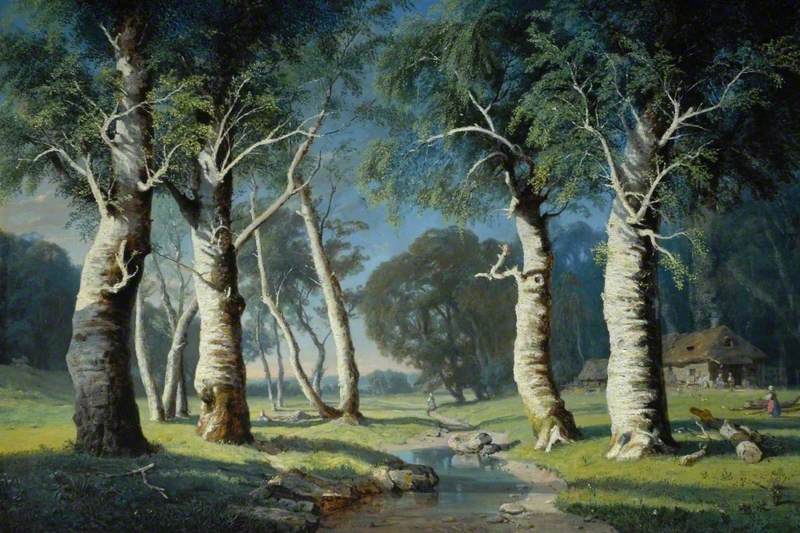

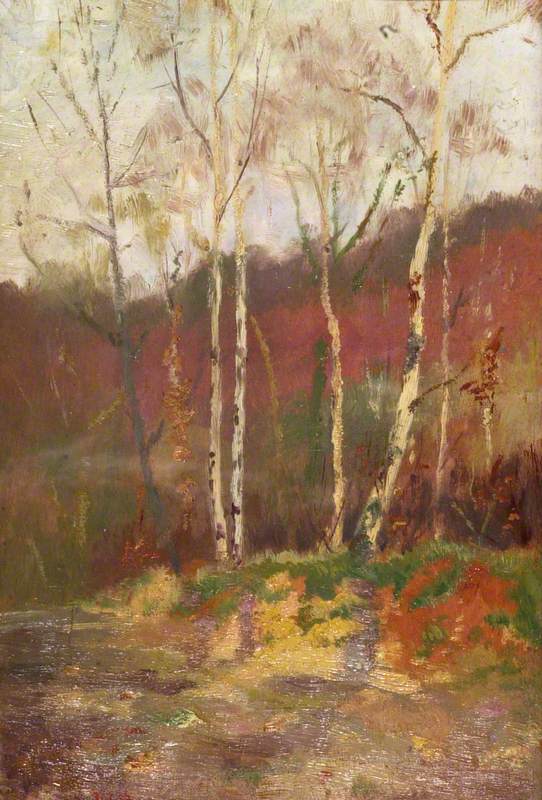

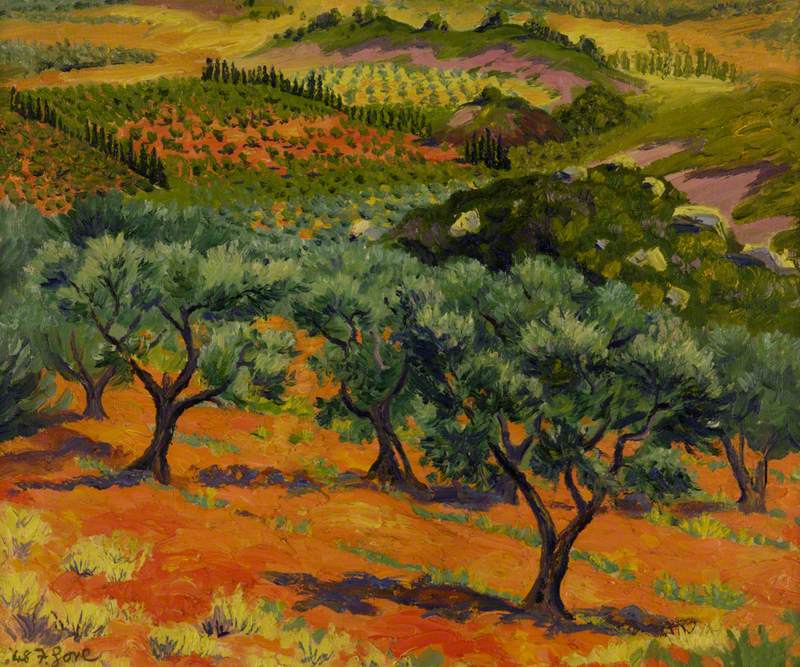

Whilst many artists have chosen to title their paintings, simply Trees, others have chosen more particularization and there are a wide variety of trees forking throughout the collection including Study of Birch Trees by Joséphine Bowes (1825–1874), Silver Birch Trees by Walter Duncan (1848–1932), Olive Trees, Les Baux by Frederick John Pym Gore (1913–2009), Oak Trees by R. Ellison, and Beech Trees by Bernard Meninsky.

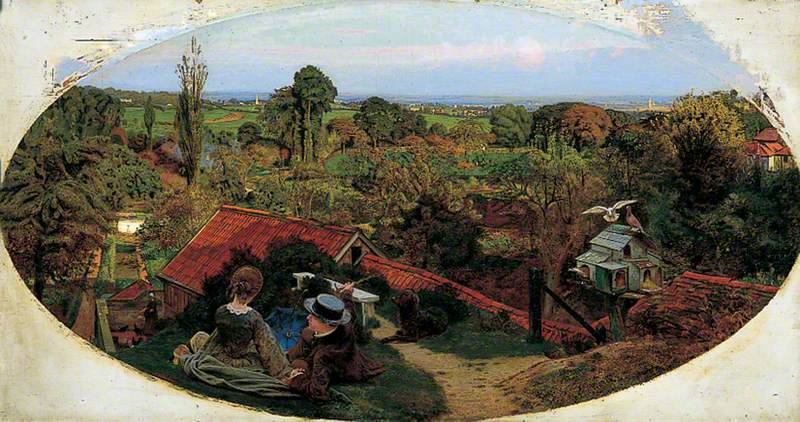

Trees are depicted in all their full glory in landscapes as in the many paintings entitled Landscape with Trees, while other painters have chosen to focus on specific parts of trees such as the powerful painting Patterned Canopy Shadows by Lynsey Ewan. Paintings depict both the height and depth of trees: one of my favourite paintings is Understorey, also by Lynsey Ewan – the 'understorey' being the word for the layer of vegetation beneath the main canopy of a forest.

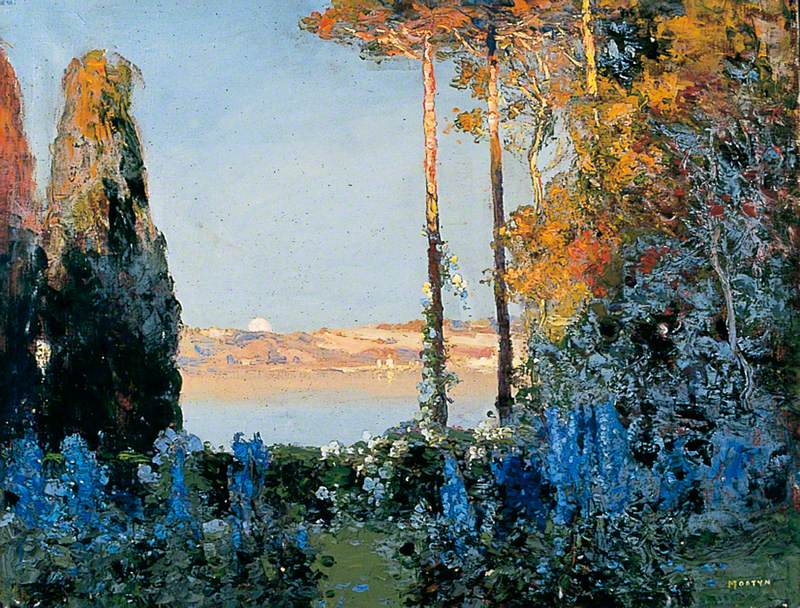

How do trees make us feel? Some painters have ascribed moods to their artworks depicting trees in paintings including Solitude by James Tyndall Midgley (b.1872) and Peace by Thomas Edwin Mostyn (1864–1930) with its wonderful colour palette of blues, golds and greens.

I'm reminded by such paintings of the increasingly popular practice of 'forest bathing', spending time in a forest to reduce stress and promote a sense of wellbeing. The Japanese term is 'Shinrin-yoku' which means 'bathing in the forest atmosphere', and was developed in the 1980s. These paintings go far in conjuring through colours and craft such an atmosphere – and looking at them did indeed have a soothing effect on my mood.

Looking at these paintings, I'm powerfully reminded of the 'deep time' collected within trees: the fact that they exist for hundreds of years, that many of them will be here long after we are gone. Many of these paintings immortalising trees will outlast the trees themselves, showing just what a potent combination is that of trees and art. Above all, in our Anthropocene age of biodiversity loss, appreciating arboreal art is a great reminder of the importance of valuing and protecting trees themselves – the 'lungs' of our world – which in turn protect and sustain us.

Anita Sethi, journalist, writer and critic

!['Phoebe Boswell: A Tree Says [In These Boughs The World Rustles]' at Orleans House Gallery](https://d3d00swyhr67nd.cloudfront.net/w800h800/artuk_stories/boswell753x1000-edited-thumb-1.jpg)