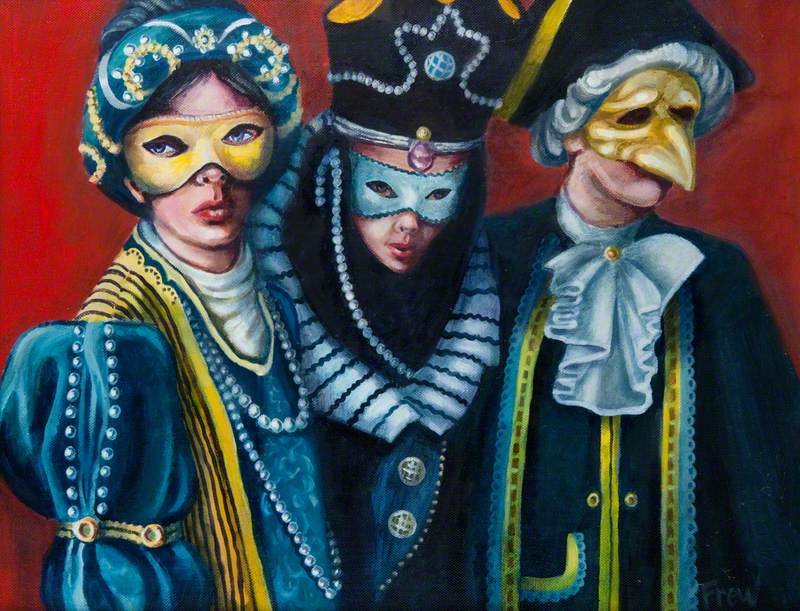

In the eighteenth century, the masquerade became popular throughout Europe – a dazzling spectacle which attracted huge crowds disguised in elaborate costumes. Its origins can be found in the fifteenth-century Venetian Carnival, May Day celebrations, and the Italian commedia dell'arte.

Individuals attending a masquerade often wore masks and they were able to transgress social, class, sexual and racial boundaries. Academic Terry Castle, in her account of the eighteenth-century masquerade, describes the event as 'a social phenomenon of expansive proportions and a cultural sign of considerable potency'. Thomas Rowlandson's Pantheon Masquerade (1809) captures the lavish and raucous nature of masquerades.

Image credit: National Portrait Gallery, London, CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

Pantheon masquerade

1809, hand-coloured etching and aquatint by Thomas Rowlandson (1757–1827) and Augustus Charles Pugin (1769–1832)

In Rowlandson's Dressing for the Masquerade (1790), four women prepare for a masquerade, assisted by older servants with aged features, who serve to show up their beauty as a scam. They dress in familiar masquerade disguises: one woman, dressed as a madwoman, holds the ticket to the masquerade which is held at the Pantheon, Oxford Circus.

Another woman, wearing a tricorn hat, is dressed as a man, while the other two admire themselves in mirrors. One woman, wearing a black mask, alters her appearance further by attaching a derrière to her behind; her fellow reveller, baring one breast and dressed in an 'oriental' costume, holds a mask, further signifying the foreignness of her disguise. The upturned chair and barking dog highlight the transgressive and upside-down nature of masquerade.

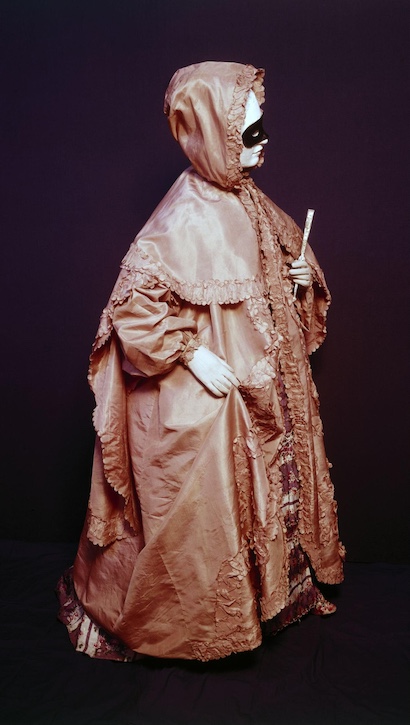

The domino was an important part of European masquerades in the eighteenth century. This was a hooded cloak worn with a mask, usually (but not always) black in colour and made of silk; the cloak originated in Venice and covered the whole body, creating the illusion of total effacement.

Image credit: Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Domino

1765–1770 (altered around 1775), hand-sewn silk by an English maker

During this period, masks had both a social and racial significance. Prior to their inclusion in the masquerade, the mask or visard was worn by female theatregoers from the sixteenth century onwards to conceal their identity so as not to compromise their reputations. When out of doors, masks were often used to shield women's white faces from the darkening rays of the sun.

Image credit: public domain (source: Wikimedia Commons)

A man riding a horse with his wife, who is wearing a visard

1581, artwork by unknown artist

Numerous eighteenth-century visual representations of masquerades depict aristocratic pale-skinned women dressed in exotic costumes, black dominos, and wearing or holding a black mask. Luca Carlevarijs' A Masked Woman (c.1700–1710) typifies this, her fan adding another layer of concealment.

The domino and a variety of masks can clearly be seen in Exhibition of a Rhinoceros at Venice (c.1751) by Pietro Longhi. Here, a group of people – including two women, one wearing a Venetian black moretta mask to conceal her identity, the other holding a mask, together with some individuals wearing white half-masks and black dominos – are privy to the exotic in the form of a rhinoceros, its horn triumphantly held aloft by the carnival impresario.

Image credit: The National Gallery, London

Exhibition of a Rhinoceros at Venice probably 1751

Pietro Longhi (c.1701–1785)

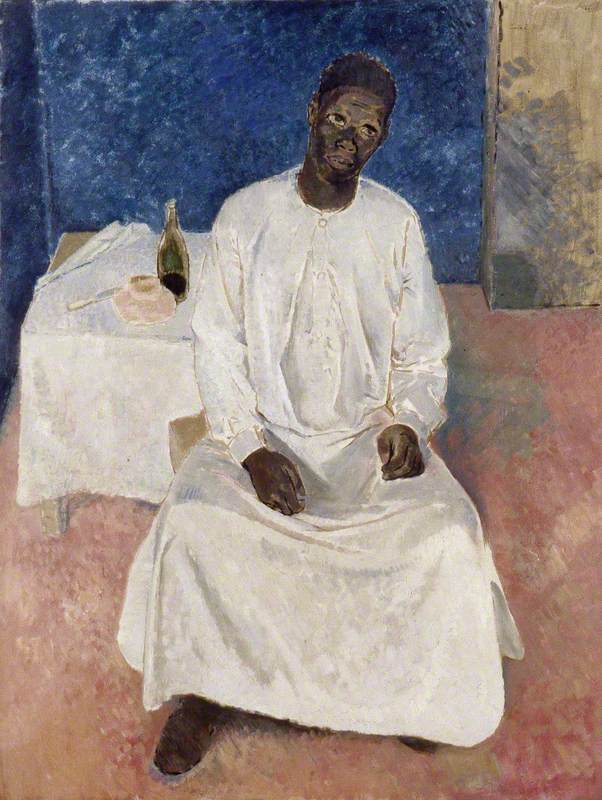

The National Gallery, LondonThe black masks worn at masquerade balls may be seen as analogous to Black skin – this racial link and the consequent associations with lust are strongly suggested in plate four of William Hogarth's Marriage a-la-mode (1743). A Black servant, whose presence alludes to an animalistic lasciviousness, is seen serving hot chocolate to the countess' guests while she is invited to a masquerade by the character Silvertongue, such as the one on the screen that he points to.

Image credit: The National Gallery, London

Marriage A-la-Mode: 4, The Toilette about 1743

William Hogarth (1697–1764)

The National Gallery, LondonIn plate two of Hogarth's A Harlot's Progress (1729–1731), an ornately liveried Black 'page', startled by the upturned table used by Moll to distract her wealthy benefactor from her fleeing lover, points to a monkey holding a mask perched on Moll's dressing table, indicating his assumed alliance with both the animal and the mask.

Image credit: National Trust Images

A Harlot's Progress: Quarrels with Her Jewish Protector

William Hogarth (1697–1764) (after)

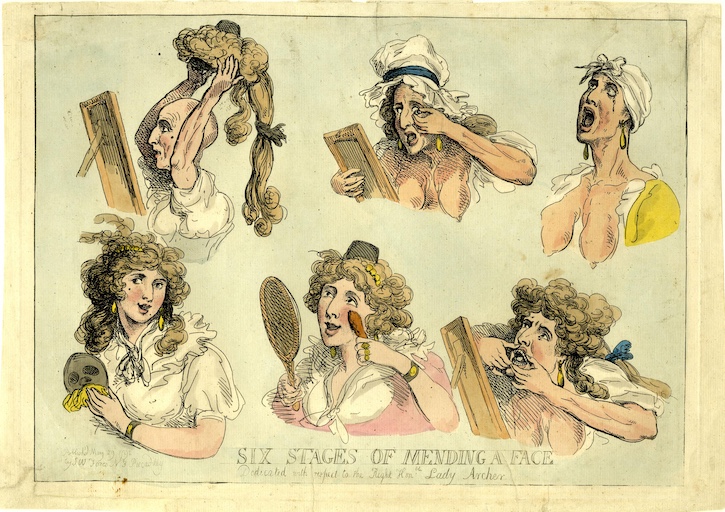

National Trust, AscottAs a metaphor for Black skin, the black masquerade mask was also believed to obscure fundamental truths about a person and, as such, was likened to cosmetics, which also veiled women's true identities. This is cruelly indicated by Rowlandson's Six Stages of Mending a Face (1792) – having completed her beauty regime, the woman resorts to wearing a mask.

Image credit: The Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Six stages of mending a face

1792, hand-coloured etching on paper by Thomas Rowlandson (1756–1827)

The term masquerade originated, together with other derivations, from the Old French word mascurer, meaning, 'to blacken the face'. I would argue that such masquerade images reflected a fragile sense of whiteness as a result of an increasing Black presence in England, growing abolitionist sentiments (the call to end slavery), and the consequent blurring of racial and social difference. In an imperialist age concerned with the notion of self and the preservation of nationhood, the masquerade offered the potential to play with racial and class distinctions, supported by pseudo-scientific reassurances of the superiority of the elite white race.

The Weekly Journal in 1718 and 1724 described the scene of one masquerade as 'a Congress of principal Persons of the World, [appearing] as Turks, Italians, Indians, Polanders, Spaniards, Venetians... not to mention the popular "blackamores", American Indians, and Polynesian Islanders'. Unsurprisingly, English masquerades were believed by their critics to be a foreign import. Castle cites one newspaper as claiming, somewhat facetiously, that, 'since the nation has been honour'd with the residence of a number of foreigners', the wearing of masks was an attempt to nullify the so-called 'superior beauties of the English women'.

Giuseppe Grisoni's A Masquerade at the King's Theatre, Haymarket (c.1724) depicts a candlelit interior populated with a number of 'turks', 'sultans', people dressed in black dominos, women attired in Turkish and oriental costume, and bewigged 'blackamores'. The image also depicts another popular masquerade disguise: Harlequin, seen here in the middle of the image, tipping his hat and sporting a phallic-like staff.

Image credit: Victoria and Albert Museum, London

A Masquerade at the King's Theatre, Haymarket c.1724

Giuseppe Grisoni (1699–1769)

Paintings CollectionOriginating in the Italian commedia dell'arte, this character – known for his childlike naivety and uncontrollable amorousness – was often depicted as being of African origin. He is portrayed in this way in Jean-Antoine Watteau's Voulez-vous triumpher des Belles (Do you want to conquer beautiful women?) (c.1714–1717). Leaning back on a statue of the fertility god Hymen, we see the black-faced Harlequin making improper advances to a startled Columbine.

The predatory and seemingly shocking coupling of these black and white characters is found again in Nicolas Lancret's Italian Players by a Fountain (c.1717–1718), in which Columbine's disinterest in Harlequin's advances is palpable. It is worth noting how the uniform blackness of Harlequin's impenetrable black mask contrasts with the carefully applied gradations of white skin: Columbine's blushing cheeks and pale décolletage, and Pierrot's ruddy face.

The amorous nature of the masquerade is boldly suggested by the tempting gaze of the sitter in Benjamin Wilson's Portrait of a Lady with Mask and Cherries (1753). She, unmasked, invites the viewer to compare the delicate pink flush of her cheeks and pale skin with the ripened red cherries. In a reversal of the effacing nature of the domino, the woman's transparent cape reveals a fusion of black and white and the potential changeability of white skin.

Image credit: By permission of Dulwich Picture Gallery

Portrait of a Lady with a Mask and Cherries 1753

Benjamin Wilson (1721–1788)

Dulwich Picture GalleryElsewhere, Woman Holding a Black Face Mask, a pastel from around 1795 by John Raphael Smith, shows a similarly self-assured, rosy-cheeked white woman, dressed in a diaphanous gown and carrying a mask depicting the caricatured features of a Black man's face. Her uncovered face, in comparison to the black mask, points to a moral fairness and racial purity. Yet this work also plays with the notion that racial identity is a removable mask. The domino that slips from her shoulder, like a second skin, appears to have left traces of its presence, hinting at the unfixed nature of race.

Image credit: Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, public domain

Woman Holding a Mask

1795–1800, pastel on paper by John Raphael Smith (1752–1812)

Eva Maria Veigel, Mrs David Garrick, with a Mask by Johann Zoffany shows the sitter simultaneously encompass the foreign, masculine and racial by her being dressed in an oriental costume, mannish waistcoat and holding a black mask between elegant white fingers. The lustre of her satin gown, complementing her sentient skin, reveals the value and assumed immutability of her fairness and civilised persona.

Image credit: National Trust Images

Eva Maria Veigel, Mrs David Garrick (1724–1822), with a Mask

Johann Zoffany (1733–1810) (attributed to)

National Trust, Polesden LaceyThe late seventeenth-century Portrait of Lady with a 'Page' and Mask is one of the starkest examples of the use of the masquerade mask to foreground Blackness as a symbol of enslavement and to celebrate the value of white female beauty. The sitter wears a ruff, designed to accentuate her white skin, in contrast to the metal collar – a symbol of bondage – worn by the 'page', who is shown gazing at the mask.

Image credit: public domain (source: Wikimedia Commons)

Portrait of a Lady with a Page and a Mask

late 17th C, oil on canvas by French School

The blurring of social difference and potential racial slippage is further explored in Return from a Masquerade – a morning scene (1784) by Robert Dighton. This print depicts a drunken woman dressed as a shepherdess, post-masquerade, travelling home in a sedan chair; her crook suggestively protrudes from the carriage. She is accompanied by a chimney sweep, another popular masquerade character, who is seen holding a white mask. I would suggest that the popularity of the chimney sweep disguise lay in its ability to simultaneously transgress class and racial boundaries.

Image credit: The Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Return from a Masquerade – a morning scene

1784, mezzotint on paper after Robert Dighton (1752–1814)

The life of a chimney sweep was a hard one and was often compared to slavery. The satirist Ned Ward described a chimney sweep as having 'negro hands and face', a belief that was echoed in 1822 by the essayist Charles Lamb, who described them as 'artificial negroes'. William Collins' work May Day (1811–1812) depicts the chimney sweeps in a way that questions their racial origins, both by the nature of their exotic clothes and their facial features.

Elsewhere, the painter Benjamin Robert Haydon, a committed polygenist – a firm believer in the biological predisposition of race and the superiority of white Europeans – uses the figure of the chimney sweep in his 1829 painting Punch or May Day to parody the Black coachman.

Like Harlequin, chimney sweeps appeared in scenes as playful figures associated with licentiousness, exuberance, and cunning, and they also served to question the indelibility of skin colour. This is seen in The Curds and Whey Seller, Cheapside, London from around 1730, in which the artist equates and compares the whiteness of curds and whey with the pale skin of the blind vendor, while also linking black skin with soot and coal: some of which has stained the vendor's hand and sleeve. The image also suggests that despite the ease with which soot can be removed, the lowly status of the chimney sweep aligned them with a troubling Black presence.

In a dramatically changing London – and in England more broadly – the spectacle of the masquerade gave elites and their less-elevated contemporaries the ability to assume disguises, safe in the knowledge that by the end of the night they would return to their original identities. Despite the variety of costumes and opportunities for role reversal, it was the wearing of a black mask that was significant, as it reflected the transitory nature of racial identities and the uncertainty of white supremacy in the face of Europe's imperialist gains.

It is no coincidence that the most derogatory and anti-Black images were constructed at the peak of the abolitionist movement in the late eighteenth century, where the freeing of Black Africans and the potential for interracial unions threatened the very foundations of white superiority.

Janet Couloute, academic and researcher

This content was sponsored by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation

Further reading

Terry Castle, Masquerade and Civilisation: The Carnivalesque in Eighteenth-Century English Culture and Fiction, Methuen & Co. Ltd, 1986

Jennifer Van Horn, 'The Mask of Civility: Portraits of Colonial Women and the Transatlantic Masquerade', in American Art, vol. 13, issue 3, Fall 2009

Meghan Kobzer, The Domino and the Eighteenth-Century London Masquerade: A Social Biography of a Costume, Cambridge University Press, 2024

Emily MacLeod, '"As of Moors, so of Chimney Sweepers": Blackness, Race and Class in George Chapman's May Day', in Ronda Arab and Laurie Ellinghausen (eds), Intersectionalities of Class in Early Modern English Drama, Palgrave Press, 2023

Aileen Ribeiro, The Dress Worn at Masquerades in England, 1730–1790, and Its Relation to Fancy Dress in Portraiture, Garland Publishers, 1984