In every large art collection built up over several centuries, there exists the possibility that some works may not be quite what they have long been thought to be. Detailed research or new information revealed through fresh examination or conservation work may call into question accepted identifications and attributions. This investigative process, and the thrill of new discoveries, certainly makes the role of a museum curator interesting.

David Steuart Erskine (1742–1829), Lord Cardross

1764–1765

Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792) (after)

The portrait collection of the University of St Andrews is no exception. Established in 1765, with the donation of an oil portrait of David Steuart Erskine, Lord Cardross, later 11th Earl of Buchan, from Cardross himself, it now contains over 100 works.

Cardross had studied at the university from 1755 to 1759: a Latin inscription on the reverse of the portrait records that he had presented it as ‘a monument’ of his ‘extreme dutifulness and gratitude’ for the education he had received at St Andrews.

The portrait collection at St Andrews grew steadily over the centuries and consists mainly of oil paintings of university chancellors, principals, professors, rectors, alumni and benefactors, many of whom are recognised figures in the social, cultural, intellectual, scientific or political development of Scotland.

Sometimes misattributed works have been reidentified relatively easily. A painting of ‘The Admirable Crichton by Titian’ was donated by Captain A. E. Borthwick around 1945. James Crichton (1560–1583?), who had studied at St Salvator's College from 1570 to 1575, was one of the most celebrated scholars that St Andrews ever produced. Reputed to be fluent in ten languages, after graduating he travelled on the Continent, where he proved to be an excellent fencer and horseman, and triumphed over various eminent professors in public debates.

Unfortunately it was clearly apparent that the work was not of the quality of Titian, and this threw the identification of the subject as Crichton into doubt too. Investigation showed that it was actually a copy of a portrait of an unknown young man by Domenichino. The original is now in the Grossherzoglich Heissisches Landesmuseum, Darmstadt. Borthwick’s ancestor had purchased the work in Paris in 1821: perhaps some unscrupulous dealer had played on his likely interest in a famous Scottish figure in order to shift the painting.

Happier discoveries are occasionally made. A badly overpainted portrait of Archbishop James Sharp, Chancellor of the University (1661–1679), famously murdered on Magus Muir outside St Andrews by local lairds who opposed his harsh suppression of Presbyterianism, was long thought to be a poor copy of a lost portrait by Sir Peter Lely, court painter to Charles II.

Conservation in the 1990s, including the removal of the thickly applied overpaint, revealed a portrait of brilliant quality. Research into the provenance discovered that the last owner, on whose death without heirs the work had been sold, was a direct descendant of Sharp through the female line. Her father had lent the work to an exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London in 1866 in the catalogue of which it had clearly been identified as a Lely: this was presumably previous to the botched restoration work which had hidden its importance. Since the University acquired the portrait in 1950 for £26.5s, it has proved quite a bargain.

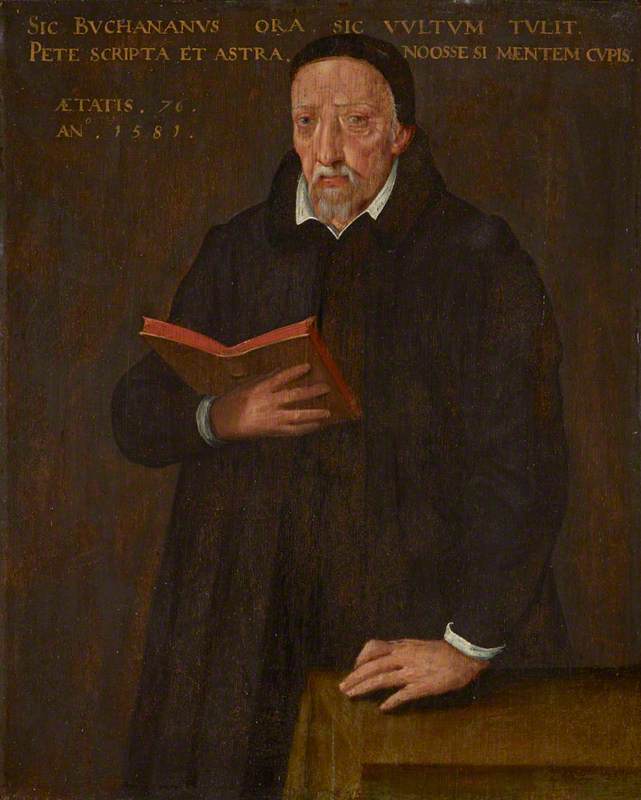

One portrait remains tantalisingly difficult to attribute. It is a small oil on board of the historian, poet and humanist George Buchanan, Principal of the University’s St Leonard’s College (1566–1570) and tutor to the young James VI.

George Buchanan (1506–1582)

c.1580

Arnold Bronckhorst (active c.1566–1586) (by or after)

In September 1580, the 14-year-old James approved a bill from Arnold Bronckhorst for a ‘poutraiet of Mr george buchanane. Viii lib’ (£8). An engraving of Buchanan by Granthomme, published in Boissard’s Icones Vivorum Illustrium (Frankfurt, 1598) seems to have been based on this portrait.

What became of the original is not known: works based on it or on the engraving are held in the National Portrait Gallery, London, the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, the University of Edinburgh, the University of Aberdeen, the Hunterian Art Gallery, University of Glasgow, and Herzog-August Bibliothek, Wolfenbüttel.

The London work bears the date 1581 and the Wolfenbüttel one, 1596. Only the St Andrews portrait bears the inscription ‘ÆTATIS. 75. / ANO 1580’ (age 75, year 1580).

Experts at the Scottish National Portrait Gallery and National Portrait Gallery, London agree that stylistically, the work does indeed seem to date from this period. Could it be that it is not a copy, but the lost original? Intrigued, I arranged various tests to establish the age of the artwork. These proved inconclusive. The original paint layer on a sixteenth-century painting should not be soluble in acetone. Various spot tests, on the book, table and one letter in the inscription revealed solubility, indicating some overpaint.

The portrait was examined with a UV light and X-rayed in the National Galleries of Scotland, in an attempt to examine the extent and condition of the original paint layer. The results revealed little more than could be seen by eye.

Cleaning revealed a worn black cap underneath overpaint around the subject’s head. Further information on the extent of the overpainting could be gained by taking cross sections with a fine instrument. These would indicate the layer structure, but only at the specific point where the sample was taken, and could not be extensively deployed without causing damage to the work.

After careful consideration and consultation with conservators and curators at the National Galleries of Scotland, it was decided that no further removal of overpaint should take place, as it might risk the stability and appearance of the fragile work. Whether the portrait does originally date from around 1580 and was the original commissioned by James VI cannot yet be established, though the discovery of new documentary information on its history or advances in scientific tests may one day shed new light. However the possibility is certainly fascinating.

George Buchanan (1506–1582), Historian, Poet and Reformer

1581

Arnold Bronckhorst (active c.1566–1586) (attributed to)

The existence of Art UK – a national database of oil paintings – is likely to assist in solving many questions of identification and attribution, allowing portraits where the identity of the subject is in question to be considered against those known to depict the particular individual, and enabling works of dubious attribution to be compared to those of known artists.

It may well raise as many questions as it answers. It is a fantastic resource, and a great asset to art historians, researchers and everyone interested in art. Happy sleuthing!

Helen C. Rawson, Co-Director Museum Collections Unit, University of St Andrews