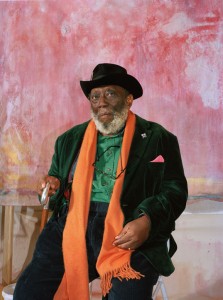

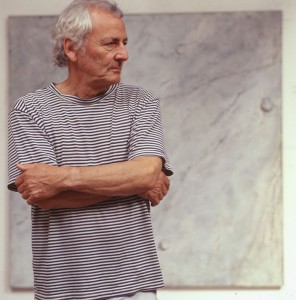

When Ian Davenport (b.1966) graduated from Goldsmiths College of Art in London in 1988, he was already garnering attention. The art world was in the process of falling for the Young British Artists, a loose group of artists who, buoyed by the new sense of freedom in London's art scene, became known for experimenting with materials and their shock tactics. The group's notoriety was fuelled, in part, by 'Freeze', an exhibition organised by Davenport's fellow Goldsmiths graduate Damien Hirst (b.1965).

The roll call of artists for 'Freeze' was prophetic: a list of individuals who would soon become bundled in with the YBA phenomenon. Alongside Davenport and Hirst, exhibitors included Sarah Lucas (b.1962), Mat Collishaw (b.1966), and Michael Landy (b.1963). As Hirst and Lucas went on to gain column inches for their shock-and-awe takes on what art meant in the modern age, Davenport emerged as a quieter force – an artist who questioned traditional painting methods and deconstructed notions of how paint could be committed to canvas.

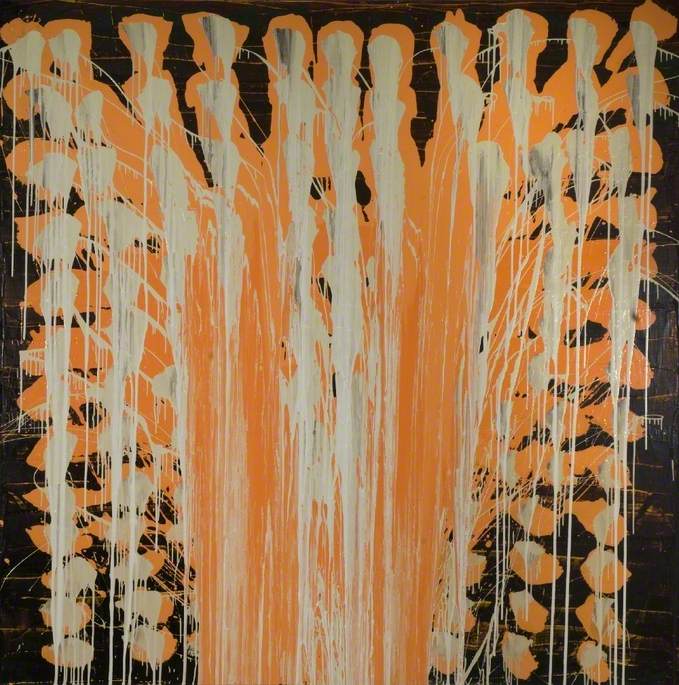

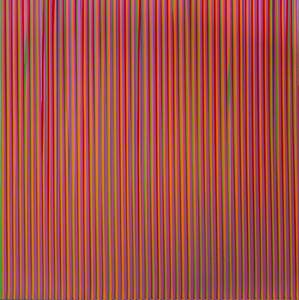

Created around the time of his final year degree show, Untitled (Orange) and similar untitled work from the time illustrate how Davenport was experimenting with paint rendering techniques. What would happen, he wondered, if brushes were left behind and electric fans were used to move colours across the surface instead? And what about splashing paint from watering cans? Or tilting canvases to drip and tumble pigments?

The results were unpredictable and exciting. Movement and chance, Davenport found, gave paint a life of its own. When 'Freeze' opened at the end of Davenport's and Hirst's final year at Goldsmiths, in 1988, Davenport was just 21 years old.

Born in Sidcup in 1966, Davenport spent time at Cheshire's Northwich College of Art and Design before completing his degree at Goldsmiths. His involvement with 'Freeze' led to an offer of representation from the Waddington Galleries, and he held his debut show at their London gallery in 1990. The year after, Davenport was nominated for the Turner Prize – he remains the youngest-ever nominee – alongside fellow 'Freeze' alumni, Fiona Rae (b.1963).

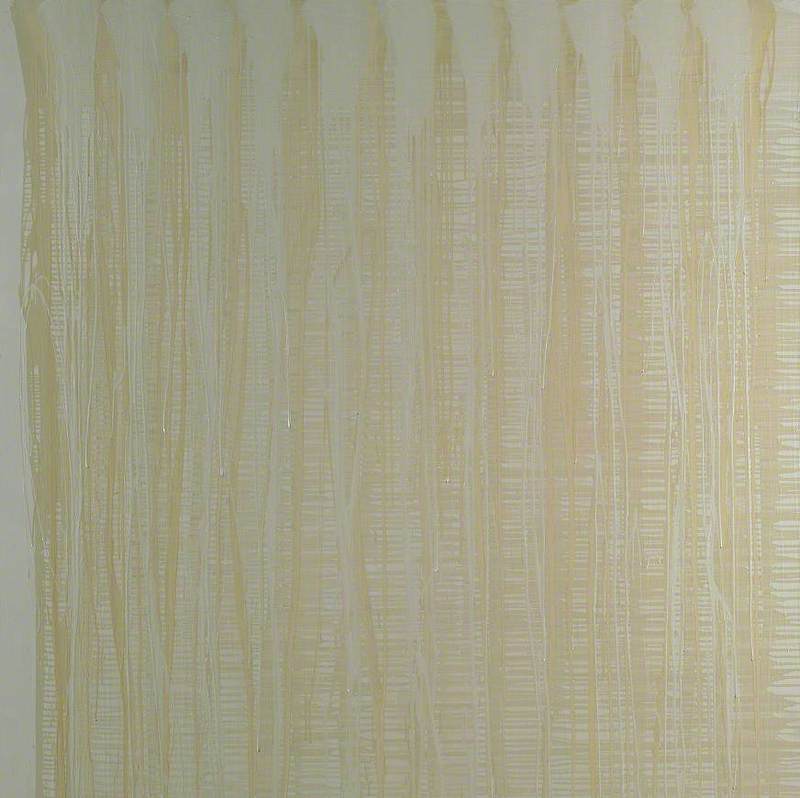

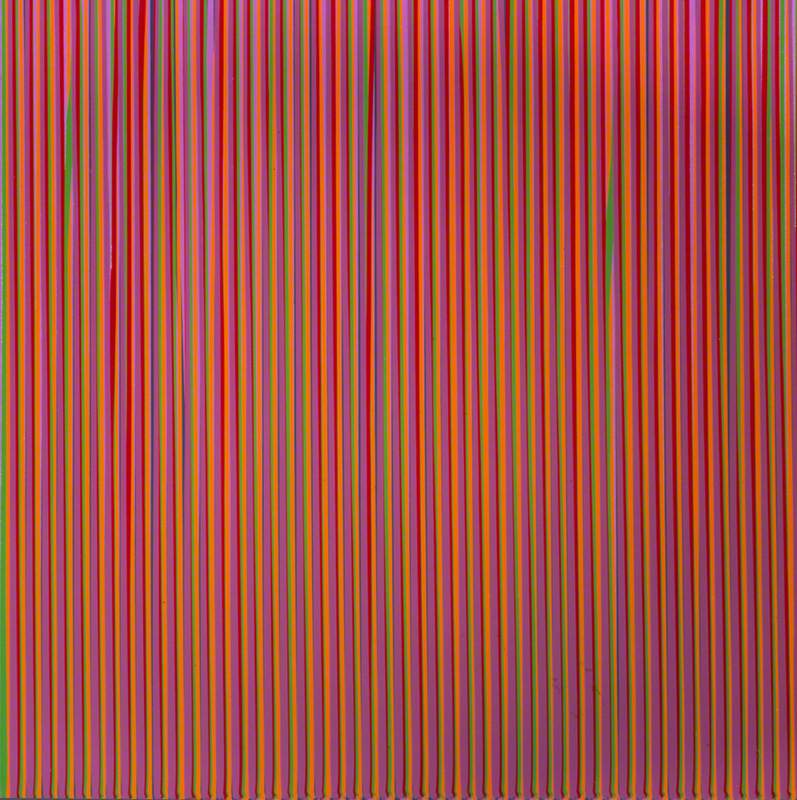

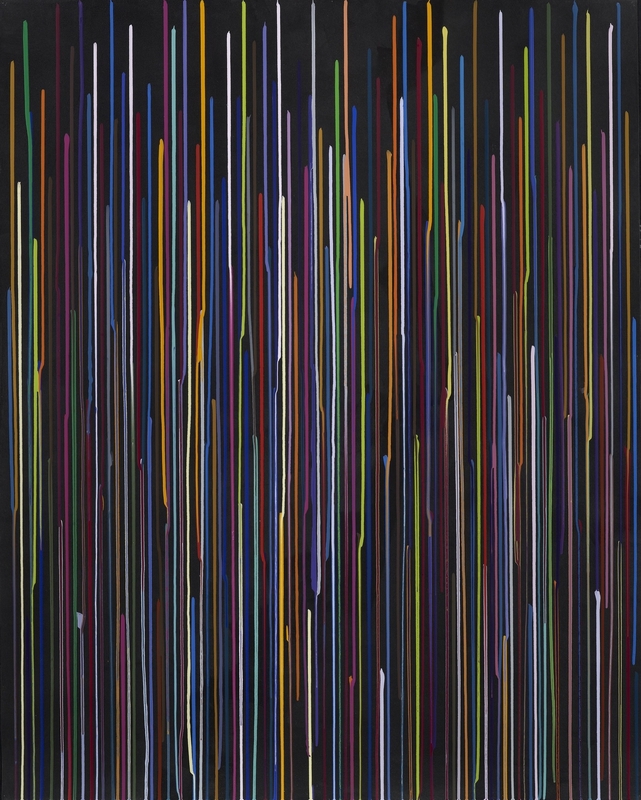

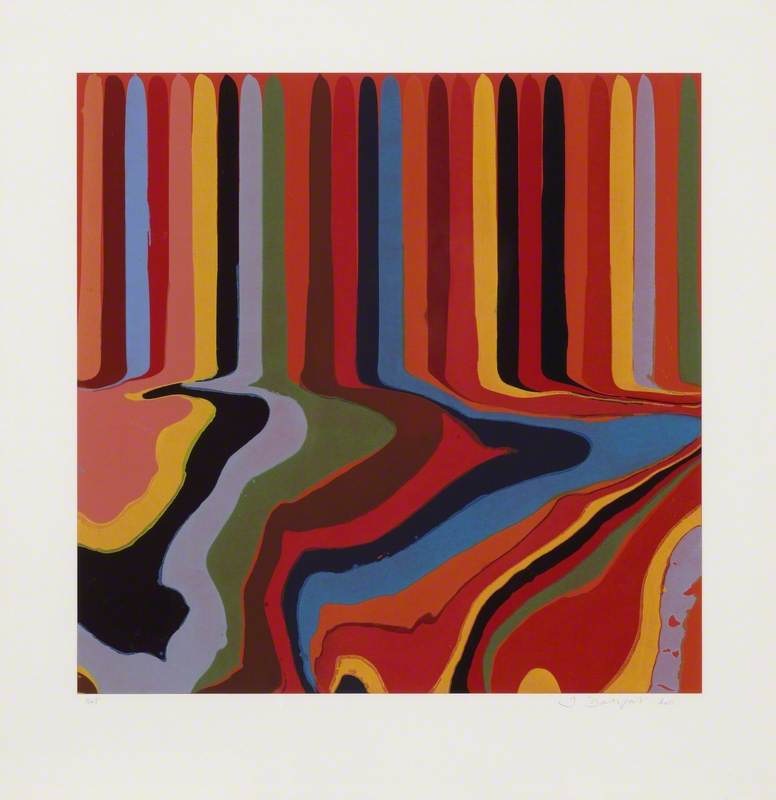

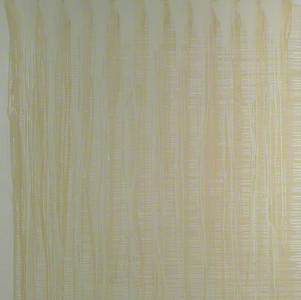

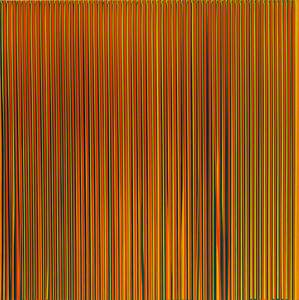

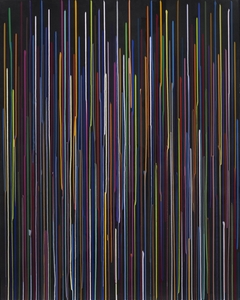

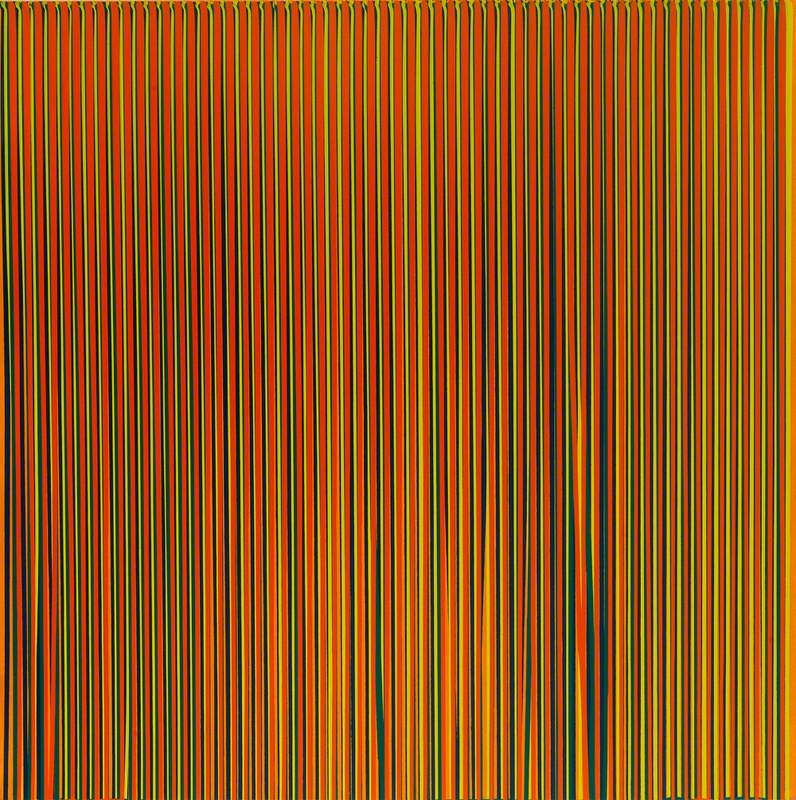

By the mid-1990s, Davenport's haphazard, painterly lines had begun to straighten as he became increasingly interested in the linear effect gravity had on paint. The title Poured Lines Painting (c.1995) immediately gives away the work's method, whereby a limited palette of acrylic paint was poured down the canvas in straight lines. The outcome is a surface that hums with pinks and greens, the side-by-side tones deceptively invoking a textured surface. There are corrugated striations here, as well as strings to be plucked.

Poured Lines: Light Orange, Blue, Yellow, Dark Green and Orange

1995

Ian Davenport (b.1966)

Davenport had intended to study sculpture at Goldsmiths until one of his tutors suggested he try painting. This makes sense given Davenport's quasi-actionist modus operandi of asking how paint might behave as a moveable, kinetic material. Davenport continued to use chance as an image-making tool, less improvisational and flamboyant than Jackson Pollock but just as intrigued by the art of the line.

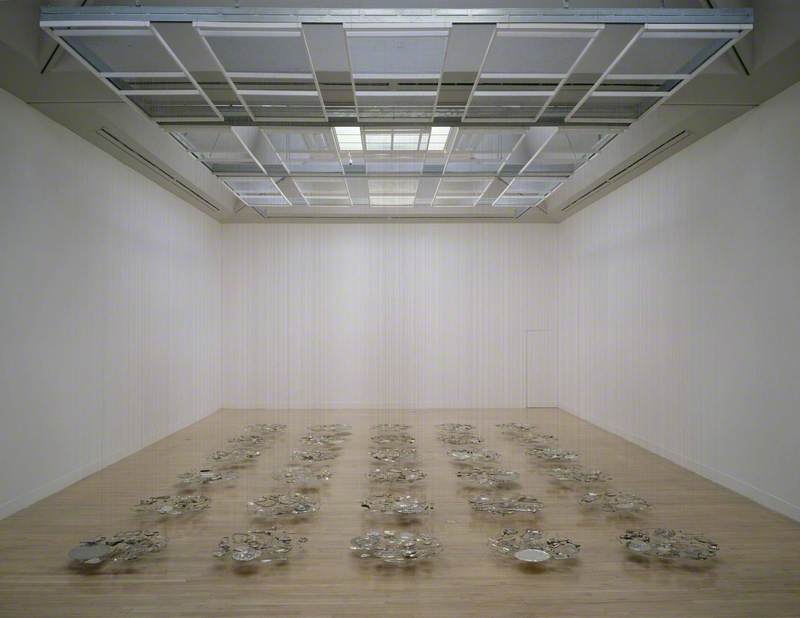

As his experiments continued, Davenport embraced the inevitable by-product of letting paint roll down surfaces: the mess on the floor. For what he calls his puddle paintings, Davenport experiments with creating distinct stripes in different colour ways that end up sliding off the vertical surfaces and wobbling onto the ground. The paintings ooze beyond the confines of the frame as colours mingle, mix and seemingly creep toward the viewer.

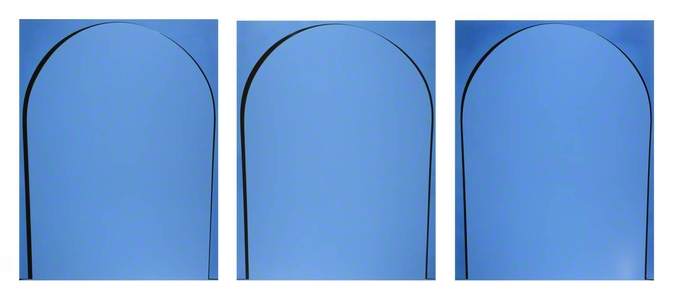

Mirrored Blue Light No.2 (after Perugino)

2023, acrylic on aluminium panels (with additional floor sections) by Ian Davenport (b.1966)

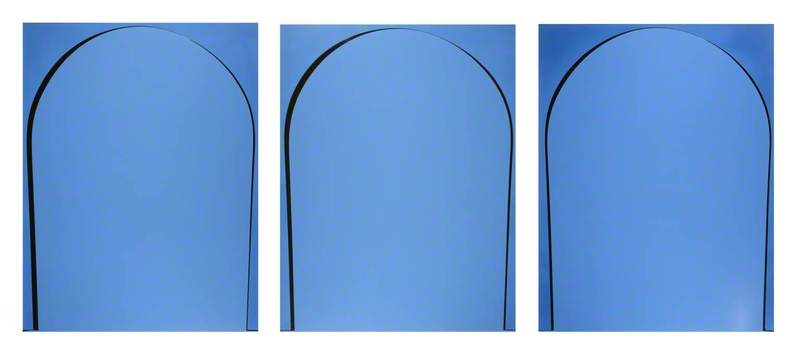

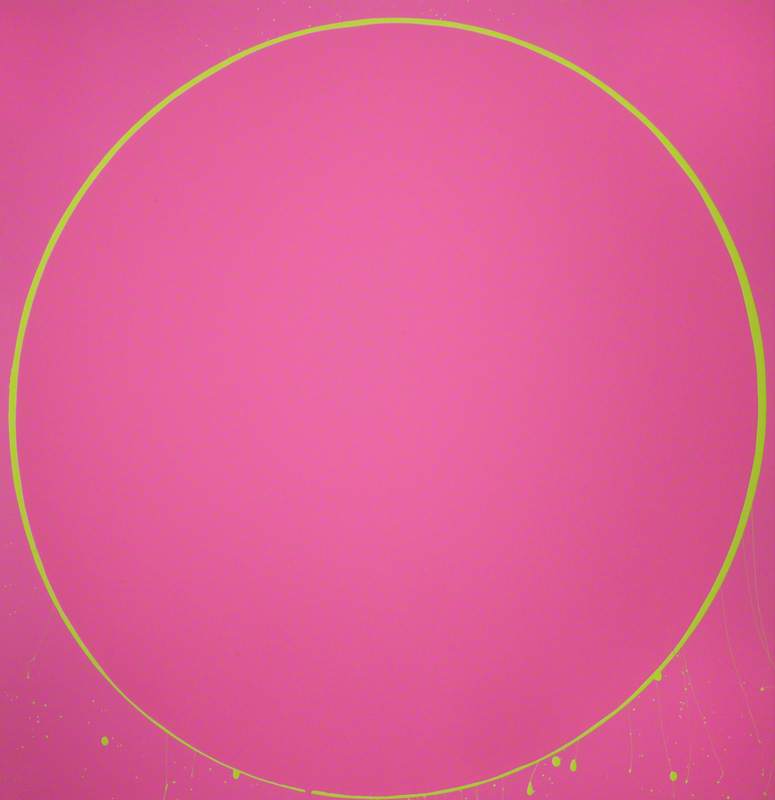

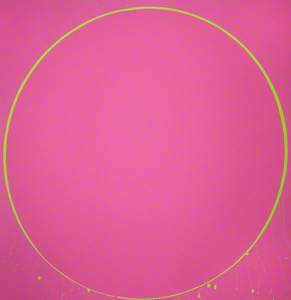

Davenport also played with moving his surface media, manipulating paint by rotating, spinning and turning his canvases and flat sheets of metal upside down to conjure circles and arches – as seen in Poured Painting: Blue, Black, Blue (1999) and Magenta/Green/Magenta (2003).

In 2006, Davenport created Poured Lines, a 48-metre-wide artwork under a bridge in South London which remains the largest permanent outdoor painting in the UK.

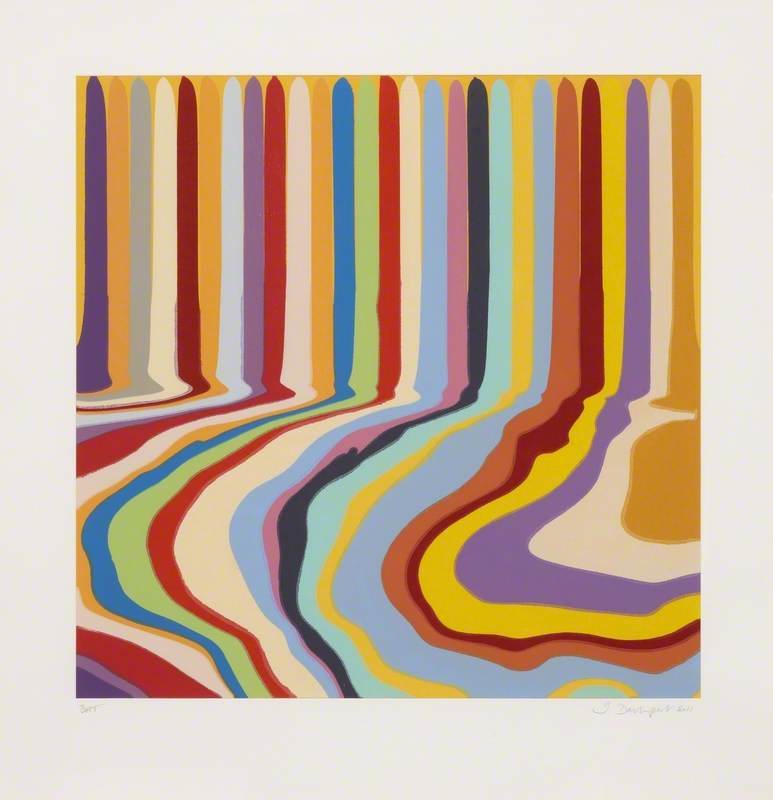

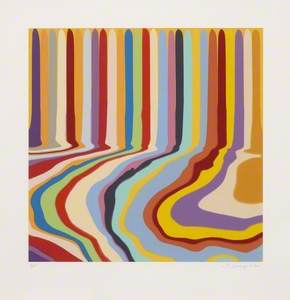

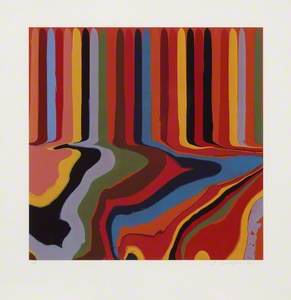

He also worked out how to transmute his puddle paintings into prints. Transferring paint laid out on glass – line by line – onto silkscreens, etching plates and then paper resulted in waterfall-like prints that include both the flat, straight rows of colour and the puddles beneath, as seen in iterations for his 'Colorplan' etching series from 2011, Azure Blue, Citric and Bright Blue.

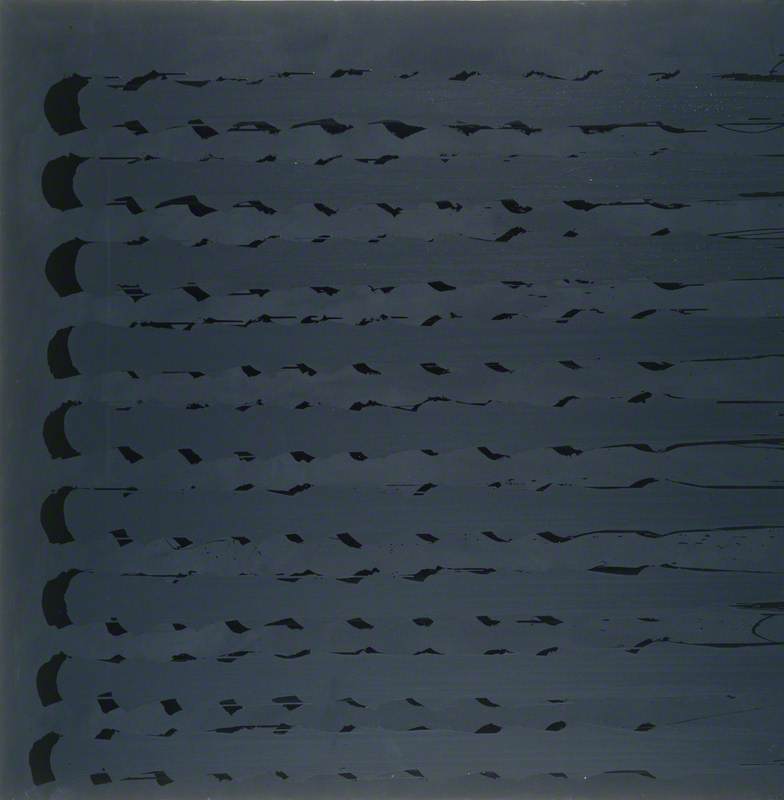

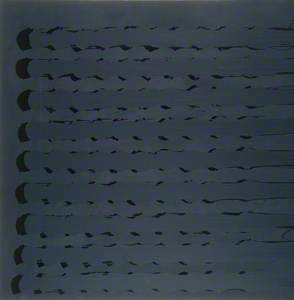

Davenport's interest in chance persisted. In a 2018 conversation with Dutch curator Robert Jan-Muller, Davenport explained how, when working on a collaborative piece with children some years earlier, the kids had decided to use plastic syringes to squirt paint at each other. Davenport adopted their idea, and Large Black Staggered Lines Drawing No. 3 is one of a series of pieces that saw him begin to use paint-filled syringes to draw colourful lines of differing lengths.

Colour could come to Davenport by coincidence, too. Talking to the Singaporean site City Nomads in 2012, he said, 'I try and work from the things I see around me. That might be the shiny surface of a new car, the colours from an industrial neon sign or more recently the sequence of colours taken from another artist's painting'.

Davenport had taken to reducing existing, revered paintings down to their basic colour elements and using the tones for a set of artworks in homage. La Cra, Harvest (After Van Gogh) uses colours from Van Gogh's 1888 painting Harvest At La Cra and Poured Triptych Etching Ambassadors (After Holbein) takes colours from Holbein's 1533 painting The Ambassadors.

Jean de Dinteville and Georges de Selve ('The Ambassadors')

1533

Hans Holbein the younger (c.1497–1543)

View this post on Instagram

As a counterpoint, 'Colourfall', his debut career retrospective staged in 2014 at Waddington Custot, included work with colours derived from palettes used in the US television show The Simpsons.

While the creative processes behind Davenport's artwork were honed from years of experimentation, their impact and appeal were immediate, striking chords with audiences beyond the gallery circuit. Sponsors and arts organisations worldwide were keen to commission new Davenport work. In 2017, he worked with Dior for their Lady Art project series and made the huge Giardini Colourfall for the Venice Biennale in association with the Swatch timepiece company.

Giardini Colourfall

2017 by Ian Davenport (b.1966), installation view, Swatch Pavilion at the Venice Biennale

Then, in 2021, came Davenport's first 'Poured Staircase'. The Chiostro del Bramante museum in Rome had asked Davenport to contribute an artwork to their 'Crazy' group exhibition that would be added to their permanent collection. In response, the artist used a staircase in the museum as the ground for Bramante Colourfall, a beautiful river of thick paint that cascaded down the stairwell, leaving puddles of colour as it dried.

Bramante Colourfall (Poured Staircase)

2021 by Ian Davenport (b.1966), installation view, Chiostro Del Bramante, Rome

A UK iteration followed in 2023 when Davenport utilised outdoor steps for Poured Staircase at urban park The Tide in Greenwich, London.

Poured Staircase

2023 by Ian Davenport (b.1966), installation view, The Tide, Greenwich

Davenport continues to push his practice forward. 'Pathway', a solo exhibition of his work held at the Cristea Roberts Gallery during this year's Frieze London art fair, showcased his largest-ever work on paper. Nearly three metres wide, Set Piece is a riot of exploding colours fired from Davenport's trusty syringes.

There were further pyrotechnics in pieces such as Red Fizzle, in which he experimented with recreating the kind of paint splatter marks that are generated by accident as a new piece develops.

View this post on Instagram

In a podcast made to accompany the 'Pathway' show, Davenport talked about his love of drumming (there are two drum kits in his London studio). He discussed how the puddling – as well as the other, more off-kilter painterly consequences of his work – are like his drum solos: free-formed and with a rhythm of their own.

Marrying these untrammelled moments with the organised rhythmic elements of his work is the key to Davenport's success. Unfettered by conceptualisation, his processes and investigations culminate in artwork that is truly democratic.

Simon Coates, writer

This content was supported by Jerwood Foundation