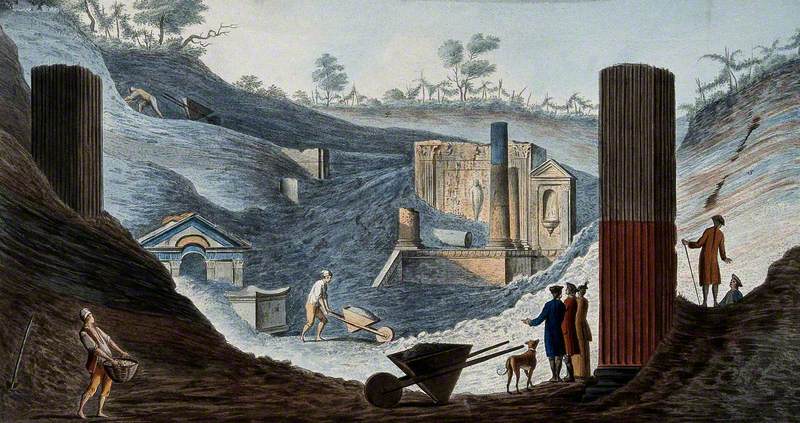

In 1768 the large-scale excavations of Pompeii and Herculaneum revealed the ruins of the city in all its residual splendour, from the theatre and Basillica to the exquisitely preserved mosaics at the Villa dei Papyri and inspired both artists and scientists alike. Although to the wealthy antique rarities were nothing new, as many aristocrats had picked Roman ruins dry of souvenirs on their grand tours for years.

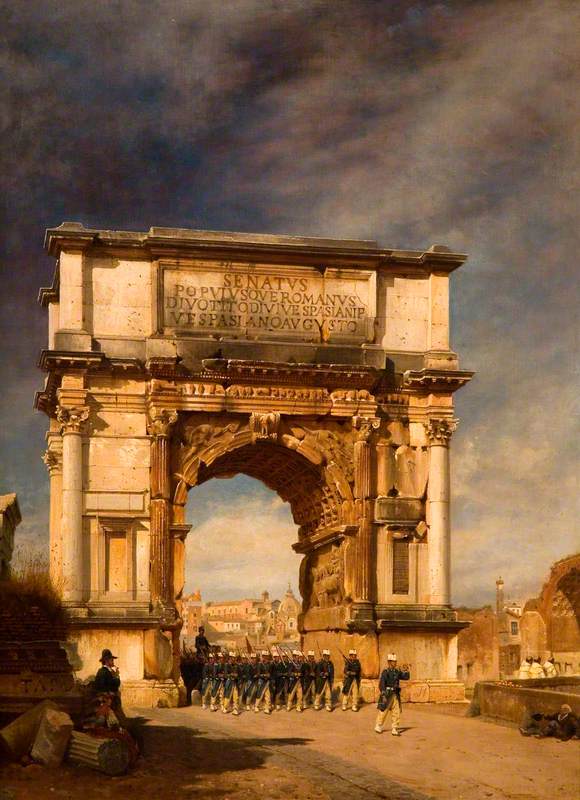

Similarly, for artists the influence of Roman architecture, rational order and literature had been prevalent in painted culture for centuries. However, the sudden exposure of this vast complex led to the ruin becoming a subject in itself, and not just the culture it represented. Suddenly watercolours, etchings, and grand paintings of ruins became the height of fashion, all focusing on looming columns, degrading slowly in the Italian sun. However, what this new subject represented beyond the physical depiction of the ruin itself, exposes more than just a record of ancient Rome.

This boom in paintings of ruins also coincided with a substantial change in how people saw themselves within the world. With the early modern period came an Enlightenment attitude towards a sense of self and human history, including a desire to understand where people came from. As a result, the excavations in Pompeii and Herculaneum that began in the late 1730s were national endeavours, seeking to uncover and record history.

Rather than interpreting Roman culture according to the virtues and valour of myth and legend, the architectural order and structures of society were being excavated and interpreted in order to substantiate people's understanding of themselves, this was not a cultural exploration but a systematic science called archaeology.

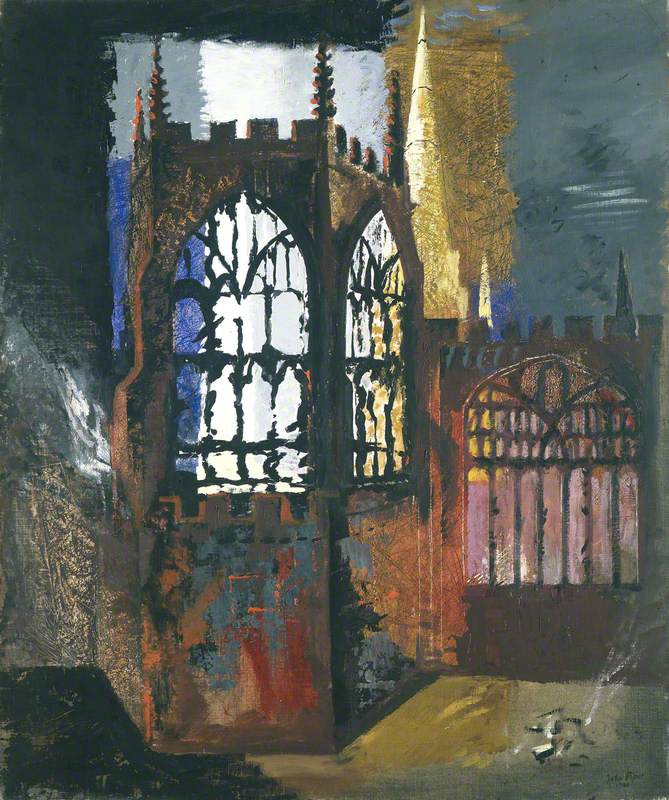

The Discovery of the Temple of Isis at Pompeii, Buried under Pumice and Other Volcanic Matter

1776

Pietro Fabris (active c.1740–1804)

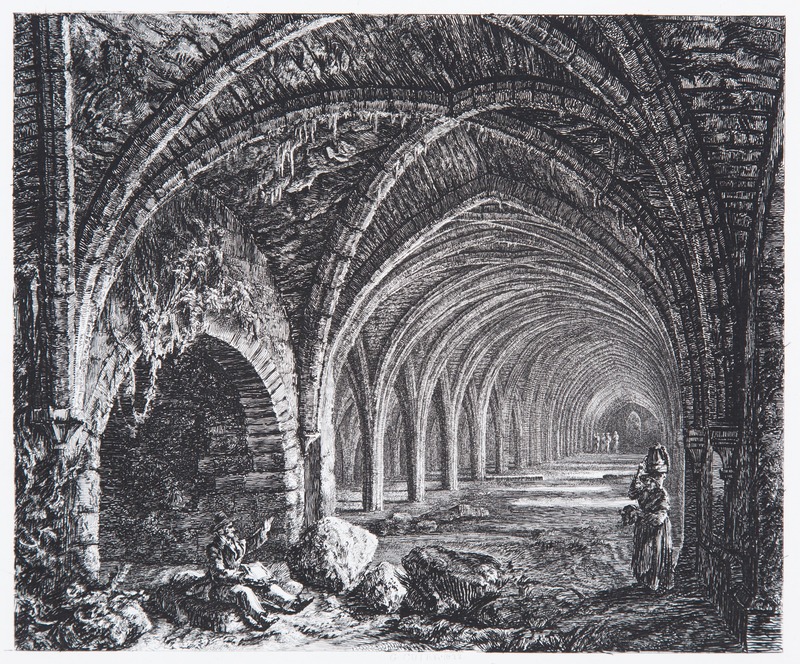

How artists responded to ruins as a painted subject changed accordingly and produced new forms of representation. With the age of the cabinet of curiosities coming to an end, and humanism giving way to enlightenment empiricism the painted ruin became something less picturesque and more contemplative. Ruins became symbolic of various layers of time and space.

On the one hand they acted in a literal sense as the remains of a bygone, but revered era of classical order and rationalism, and existed firmly in that past. But at the same time, they were being painted as part of the contemporary eighteenth-century interest in recording the world, and the ruin acted as a piece of historical data that was being reproduced in an artistic form.

These painted ruins represent complex exchanges between different times and artists responded to this in different ways. Some actively sought to display the multi-faceted timescales displayed in ruins to produce entangled and imagined images that could be interpreted as one of the earliest pieces of science fiction, such as the French artist Hubert Robert.

Nicknamed, Robert des Ruines by Diderot, he produced a vast number of paintings featuring ruins and their shifting timeframes and meanings. For example, in his Pyramid of Cestius, Rome, currently in the collection at the Museum of Sheffield, Robert depicts the Roman ruins of the past alongside a contemporary group, contemplating the space and structures.

Leaning against the rubble the figures gesture towards the ruins, turning back to discuss it among themselves. The Pyramid in the background falls away, half submerged in shadow and overgrown with a haze of vines. The more prominent feature of the ruin is the large-scale statue, staring off into the distance, but even this simply echoes the gestures of the group in the foreground, whose dynamic chatter and brightly lit presence draws the eye far more than the ruin in the title. It is clear that they are the subject but then why include the ruin?

Rather than recording the ruin, Robert is recording its impact, its new meaning in his world rather than the world from which it came. The past as Robert represents it here is a subject for the present and for the contemporary visitors to the site. It is an object, firmly located in the past and shown to be so in its degraded appearance, its value is historical and archaeological, a message reinforced by the figures discussing it, a self-referential painting of two points of history.

As Robert's career progressed his interest and anxiety concerning the ruin begins to take on a more poignant message. He moved beyond the parameters of the antique ruin and looked to the ruins of his own time. Robert began to paint Paris as he witnessed the turmoil of the French Revolutions that tore the country apart, politically and physically. The aggression and violence that came from overturning the monarchy left its permanent mark on Paris, the remnants of the barricades scaring space and burning holes in the fabric of the city.

Robert painted the ruins among the rubble, and the distorted shapes of the city, particularly cathedrals and churches that were explicit symbols of the king's divine right to rule. Attacking the churches had the same cathartic effect as attacking the monarchy and for Robert this left an ethical anxiety that is evident his paintings.

In The Dismantling of the Church of the Holy Innocents from 1785, Robert records the ruin as something brought on by people, not time.

The Dismantling of the Church of the Holy Innocents, Paris, 1785

c.1785–1787

Hubert Robert (1733–1808)

The gaunt, cavernous window frames that had once contained bright stained glass are now voids. The sun coming through illuminates in the harsh light of day the people picking through the remnants of the structure, further reducing its presence as they remove the valuables and useful materials lying amongst the rubble. These are the ruins of the present and comparing it to The Pyramid of Cestius, draws out Robert's anxiety over the state of the city.

The Pyramid of Cestius showed the past viewed from the present, here Robert's ruined church shows his present but considers the future. Having painted the residual grandeur of the eternal city, still standing thousands of years later Robert then faced the ruins of Paris produced by the people around him, raising their legacy to the ground.

Robert turned his attention to how these ruins of his own time would not last, questioning whether there would be anything left to contemplate in years to come. If the spaces of the city were being torn apart what would be left to remind people of the great architecture and cultural history of France?

This may seem to draw out more than necessary from these paintings, but looking at Robert's most famous series, held in the collection at the Louvre, shows how prevalent his ruin anxiety was. Completed in 1796 Robert painted the Grande Gallerie at the Louvre in two states. One showed the space as it was then, imposing, rational and filled with the best France had to offer, a monument to the Nation in all its cultural and artistic glory.

The other, entitled Vue imaginaire de la grande galerie du Louvre en ruines, shows the space destroyed.

The roof has caved in, and vines creep over the edges of the arches and columns enveloping the space in the inevitable return of nature. The odd frame still hangs on the wall, its contents long gone, the great artists of Robert's time being removed from the building's legacy.

What remains intact is not the monumental French museum, but classical sculptures. Bronzes and marbles stand to the right and left, disturbed but undying. The remnants of the eternal city remain eternal, and yet the remains of Paris are disposable and decaying in what seems to be the very near future judging from the clothes of the looters wandering the ruins.

This is science fiction, as many modern authors and artists of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries have imagined the destruction of our world, Robert was doing the same thing, hundreds of years earlier. It is strangely reassuring to know people have always been worried about the same things, but it is more interesting to know where it started.

The late eighteenth century was a turning point when history and archaeology as prevalent academic subjects were being formed. This awareness of the past and people's place within it caused thinkers and artists to reflect on their own time, and their own legacy, particularly in relation to the chaotic and violent experience of modern nations at the turn of the nineteenth century.

For Robert as a witness to the world in ruins and comparing them to the ever-present Rome, he saw these as a substantial source of concern. These three paintings summarises Robert's anxiety, from recording his own world to imagining its destruction. Concern with memory and legacy, how we are remembered is the key feature of the painted ruin.

Kitty Whittell, researcher