‘Bomb damage is in itself picturesque.’ The words of Kenneth Clark, art historian and Director of the National Gallery in London at the height of the Blitz, reveal the emergence during the Second World War of a new type of beauty found in bombed ruins. Architectural historian J. M. Richards, author of The Bombed Buildings of Britain (1942), described the romantic beauty in the bomb ruins, praising their ‘intensely evocative atmosphere.’

Home Front: Churchill inspecting the ruins of Coventry Cathedral

Photographs of bomb damaged buildings were reproduced in the daily and weekly newspapers and there appeared to be little discomfort in acknowledging the pictorial effects of bomb damage: they were vivid, spectacular, picturesque and even surreal and they needed to be recorded before they were cleared away or robbed of their visual appeal.

The aim to preserve and record the ruins of wartime Britain and its architectural heritage was realised by the creation of the War Artists Advisory Committee and the Recording Britain project. Artists were sent out to depict the war at home and abroad and to celebrate a native tradition of British landscape art; the projects favoured a neo-Romantic sensibility and subjects drawn from everyday rural ways of life that were threatened by war and modernisation.

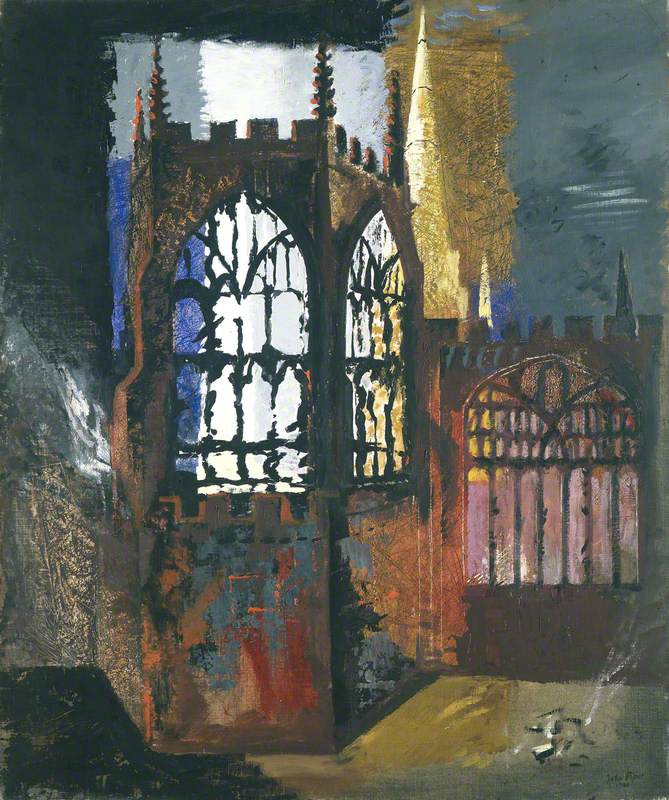

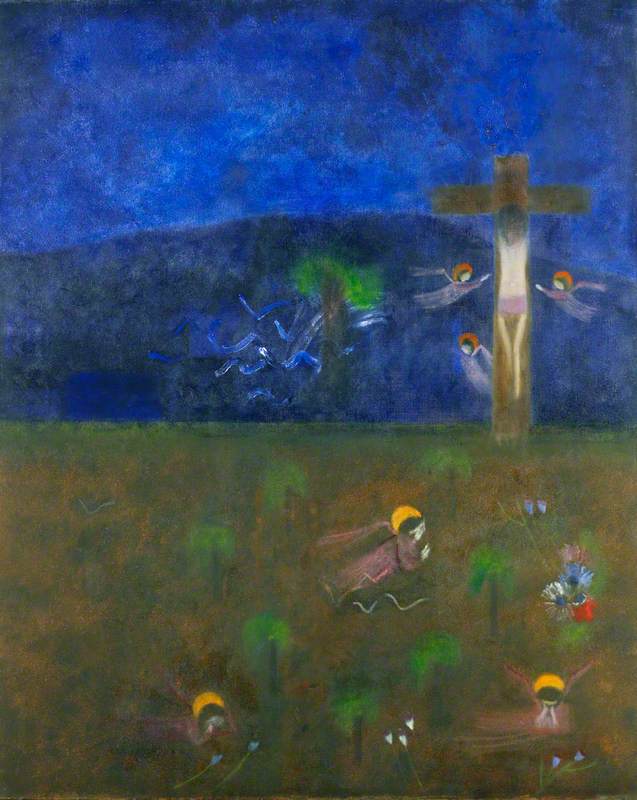

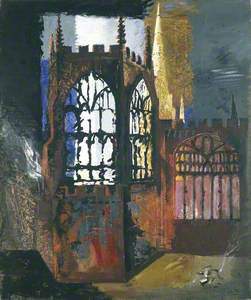

The artist John Piper worked for both the War Artists Advisory Committee and Recording Britain, creating pictures that recorded some of the most significant ruins of the war and captured the distinctive visual power and beauty associated with the bombing at this time. The city of Coventry was targeted by the Luftwaffe in 1940 because of its strategic importance as a centre of engineering and industrial manufacture; it was subject to some of the worst destruction to affect any British city during the war, including the ruination of its medieval Cathedral.

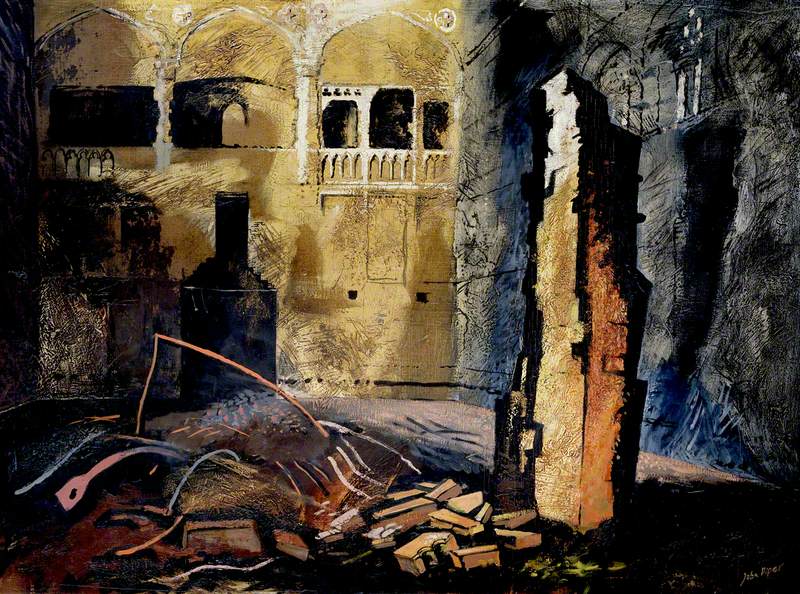

Piper’s paintings of the ruined Cathedral, now in collections at Manchester Art Gallery and Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, foreground the burnt and blasted contours of the remaining medieval walls and tracery. Colours are muted and the surfaces are incised and scarred; beauty and destruction are juxtaposed in a style that gives visual form to Kenneth Clark’s ideas of picturesque bomb damage.

Interior of Coventry Cathedral, 15 November 1940

1940

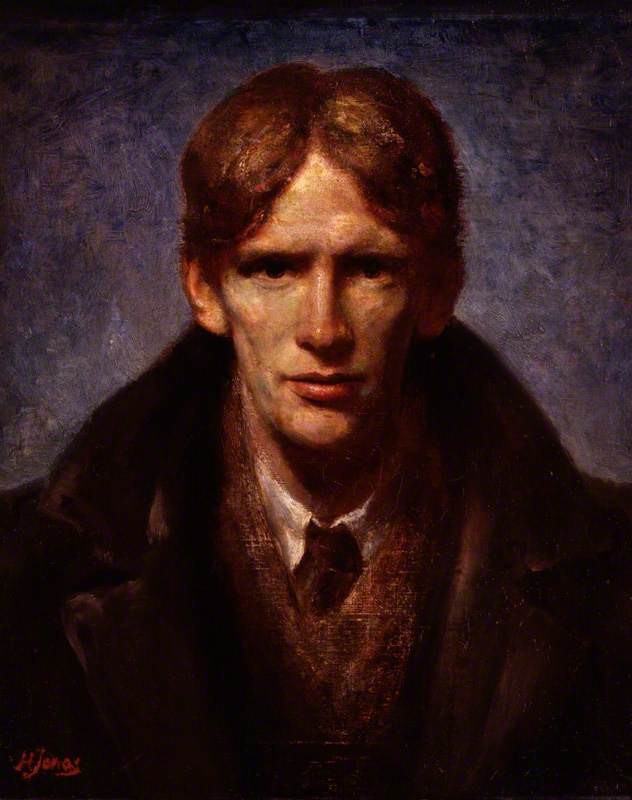

John Piper (1903–1992)

The ruins of Coventry Cathedral were one of the best known and most resonant images of the war; religious services were held amidst the rubble shortly after the raids and the question of how it should be rebuilt was addressed almost immediately. In the end, it was decided that the ‘new Cathedral should grow from the old’ and that the ruins should be embedded in the new design, a resolution that acknowledged the visual and symbolic importance of the image of ruin and the role of Piper’s art in defining its beauty.

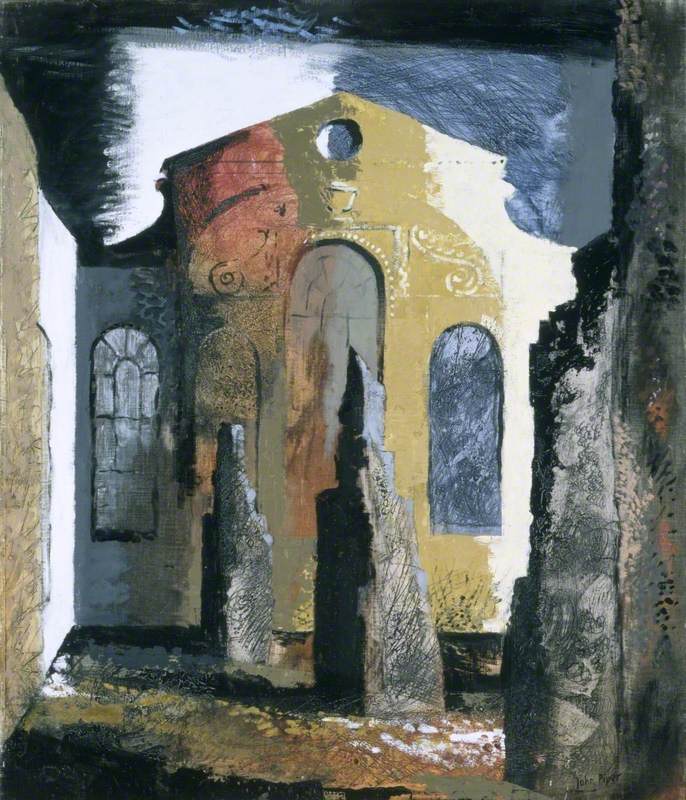

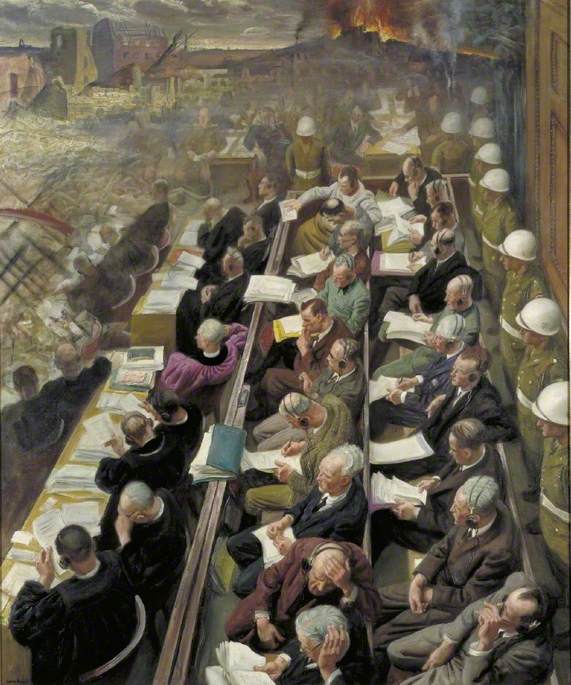

The Ruined Council Chamber, House of Commons, May 1941

1941

John Piper (1903–1992)

In the nine months between September 1940 and May 1941, the main period of the Blitz, London took the brunt of the bombing and was the target of over half the night raids on Britain at this time. Piper depicted the blasted remains of the Council Chamber of the House of Commons and the City Churches. Christ Church Newgate Street was one of many City Churches ruined by the bombing in these months. The tottering structures still existed as powerful architectural forms that were monuments to the past and reminders of the war; they were romantic ruins created by violence but yielding a stillness and restful quality.

By August 1944 the appreciation of ruins was so thoroughly installed in the national way of seeing that a number of key figures in British cultural life, including Kenneth Clark, John Maynard Keynes and T. S. Eliot, sent a letter to The Times calling for the preservation of certain ruined City of London churches as commemorations of the past, with designs for gardens and seated sanctuaries and the integration of bomb-damaged churches within new developments. Piper and other artists and critics interpreted ruins through the enduring and traditional aesthetics and values of the Romantic movement; the trauma of warfare had, paradoxically, been transformed into a new and unexpected beauty.

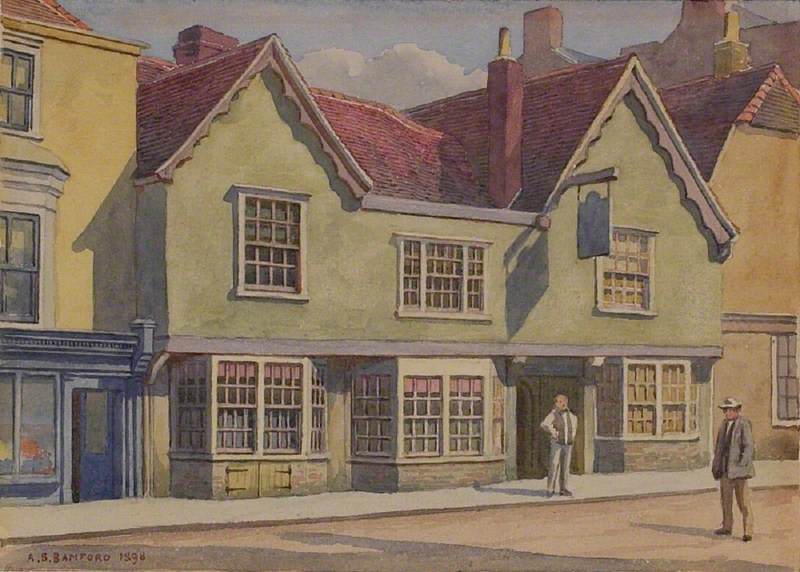

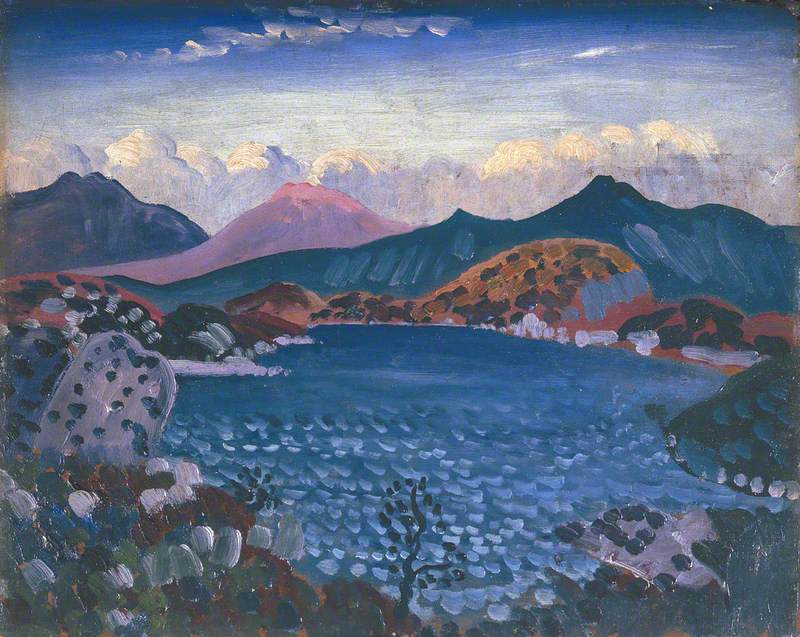

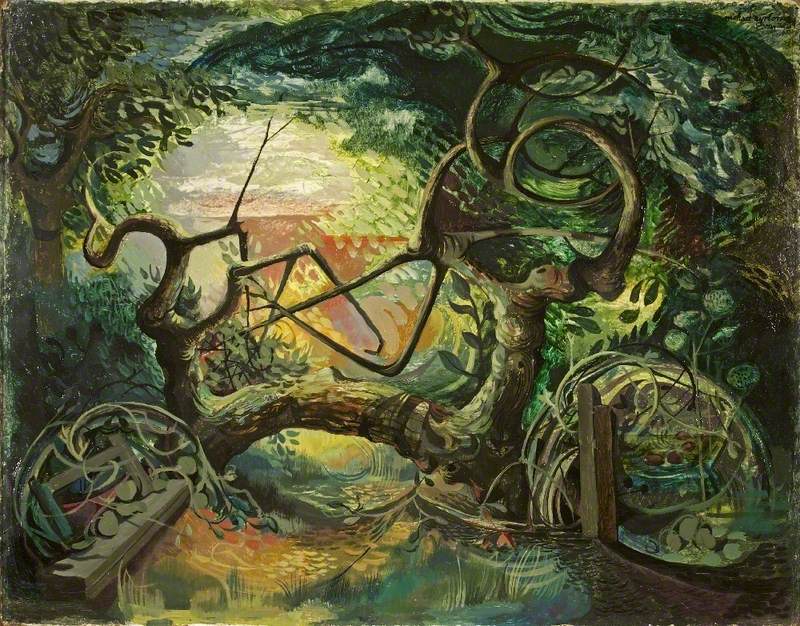

When Piper was not depicting war damage, he was painting older historic ruins. Seaton Delaval was a country house in Northumbria that had been built in the 1720s to designs by Sir John Vanbrugh.

It had been gutted by fire in the 1820s, and in 1945 Piper described its appearance as ‘Ochre and flame-licked red, pock-marked and stained in purplish umber and black, the colour is extremely up-to-date: very much of our time.’ In his painting, the ruined remains of the great house emerge from the thick impasto of their surroundings. Black lines trace the shapes of former grandeur that are stained by layers of red paint; a ‘magnificent modern ruin’ standing against a dark, stormy sky. It is a relic of the past that speaks to the temperament of the present.

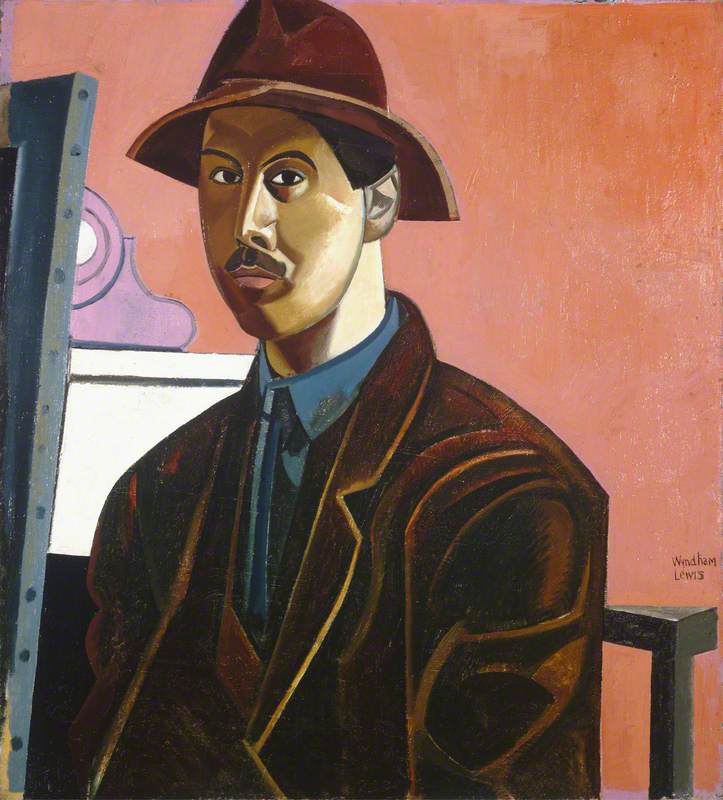

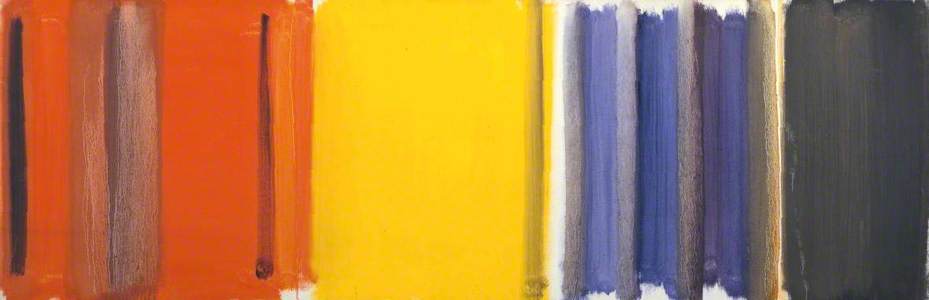

John Piper created images that expressed the muted colours and feelings of wartime and a romantic notion of art and nation. There were others, however, who regarded the poetic atmosphere of Piper, John Nash and other artists associated with neo-Romanticism as dull and monochromatic.

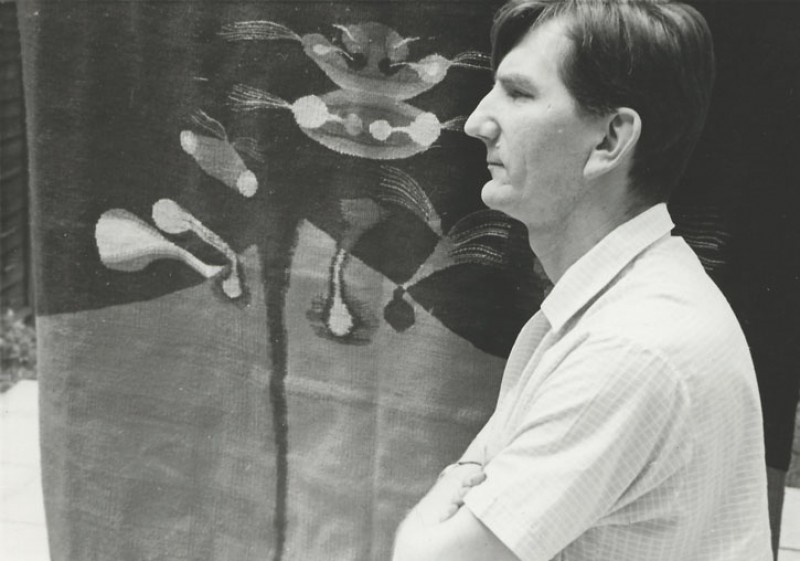

For the painter, writer and curator Patrick Heron colour was the fundamental language of modern abstract art and throughout his artistic career, Heron kept up a sustained critique of the diluted greyness of contemporary British painting, as in Scarlet, Lemon and Ultramarine. The future, it seemed, had moved from the ruin and lay in colour. But that is another story.

Lynda Nead, Pevsner Professor of History of Art at Birkbeck, University of London

Lynda's latest book, The Tiger in the Smoke: Art and Culture in Post-War Britain is published by Yale University Press