In 1907, soon after Jacob Epstein (1880–1959) arrived in London at the age of 25, he was offered a momentous commission. The young architect Charles Holden invited him to carve no less than 18 over-life-size figures for the façade of the British Medical Association's new headquarters in The Strand.

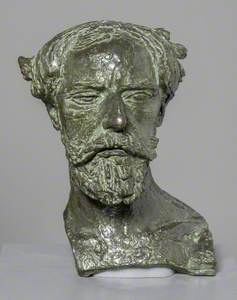

Epstein, who grew up in New York as the son of Russian-Polish parents, had been an art student in Paris between 1902 and 1905. Already fascinated by ancient and 'primitive' sculpture, he proposed to Holden that the 18 figures should be 'noble and heroic forms to express in sculpture the great primal facts of man and woman.'

Image credit: Stephen Richards (source: Wikimedia Commons)

Zimbabwe House, formally the home of the British Medical Association, The Strand, London

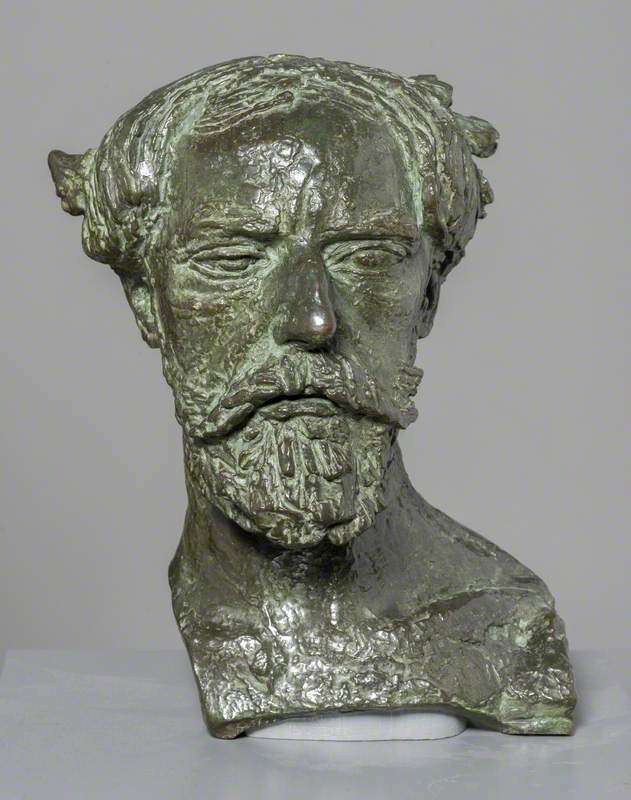

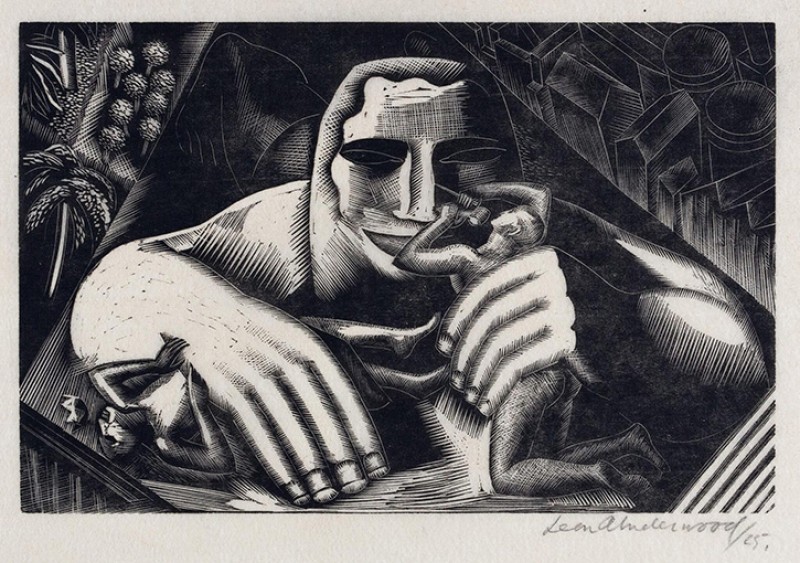

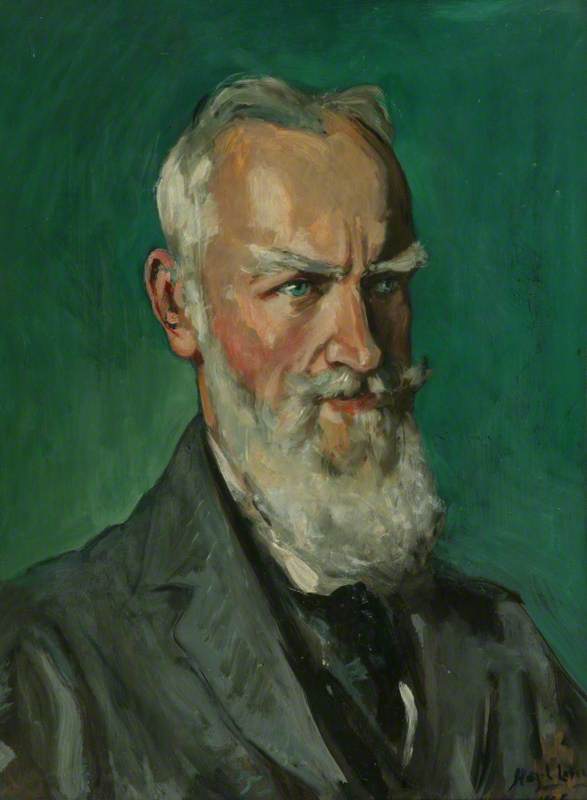

1908, Jacob Epstein (1880–1959)

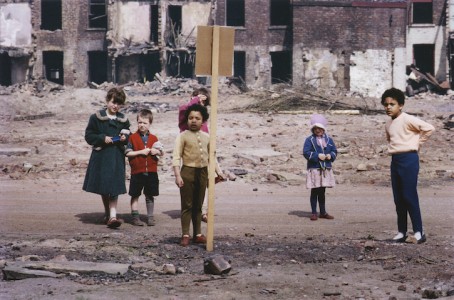

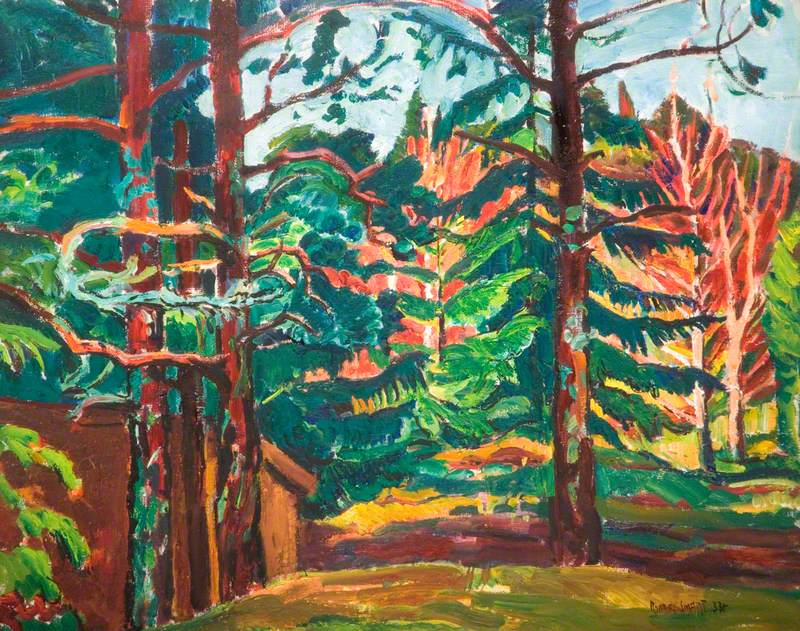

The commission was granted, and by 1908 Epstein had completed it with an extraordinary amount of confidence, intensity and verve. As his preliminary study for Maternity reveals, he was fascinated by the theme of procreation. And in the final Maternity carving, a sense of tender privacy reveals Epstein's profound understanding of the relationship binding the mother to her child. Although her milk-laden breast is exposed in all its fullness, no hint of deliberate provocation mars this absorbed figure. Like all the other carvings on the façade, she is characterised by a stillness and dignity which should have precluded any accusations of immorality.

But an enormous public furore erupted when Epstein's figures were unveiled on the British Medical Association building in 1908. A lot of the scandalous indignation focused on the nakedness of Maternity herself. Although an impressive range of artists, critics and curators rallied to Epstein's defence, the scandal had a damaging effect on his prospects as a maker of large-scale public carvings. Even so, he stayed utterly determined to emancipate British sculpture from the puritanism, hypocrisy and prurience of society's attitudes towards the delights of the flesh, and his audacity remained courageous.

Equally innovative was his adherence to the inspiration of cultures that lay far outside the approved Hellenic and Renaissance models. He haunted the British Museum, where he found himself particularly excited by 'the Egyptian rooms and the vast and wonderful collections from Polynesia and Africa.'

Epstein's status as an outsider, a New York Jew, enabled him to view Britain from the impatient vantage-point of a foreign invader. Although he became a British citizen as early as 1907 and made London his lifelong home, Epstein always remained at a certain remove from the culture of his adopted country. This sense of critical distance made it easier for him to identify the weaknesses of conventional British art and offer a powerful alternative of his own.

Image credit: Jim Linwood (source: Flickr)

Oscar Wilde's Grave, Pere Lachaise Cemetery, Paris, France

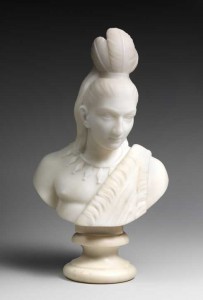

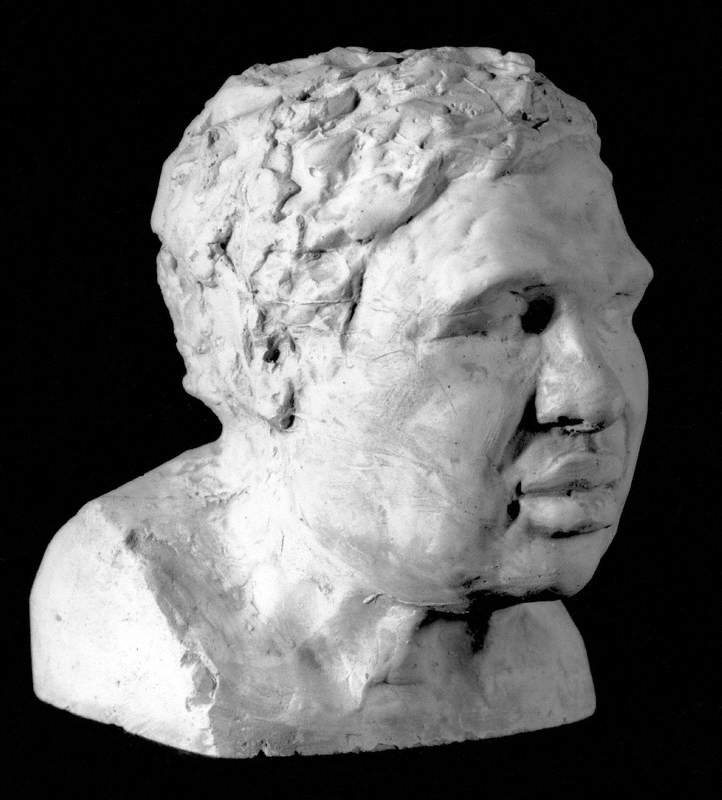

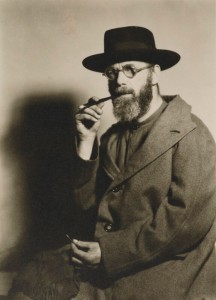

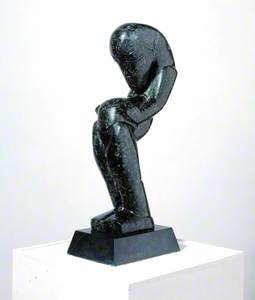

Around 1910 he created Sun Goddess, Crouching, a limestone carving where radical simplification of form shows just how much Epstein had learned from 'primitive' art. Even more controversial was his monumental Tomb of Oscar Wilde, commissioned for the Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris. When unveiled in 1912, the authorities were outraged by the prominent nudity of this 'winged demon angel', and it quickly became scandalous.

Jacob Epstein In Front Of His Sculpture For Oscar Wilde's Tomb pic.twitter.com/FcDl6s69vi

— Pauline Hughes (@Paulineceramics) December 24, 2016

But Epstein met Constantin Brâncuși in Paris, and the Romanian's experimental work gave him enormous stimulus. So did Amedeo Modigliani, who was busy carving a series of elongated stone heads.

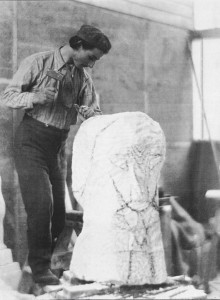

By now Epstein had become known, and described by one critic, as 'a sculptor in revolt, who is in deadly conflict with the ideas of current sculpture'. He insisted on the importance of carving directly, retaining manual responsibility for every blow of the chisel and allowing the intrinsic character of his stone to affect the fundamental identity of the sculpture. After returning to England in 1913 he rented a bungalow near Hastings for three years.

Here, working with great concentration and intensity, far away from hostile urban vituperation, he carved female figures in flenite and three pairs of mating doves in marble. They are among his most impressive achievements. Epstein's commitment to the overt exploration of sexuality is especially clear in his third Doves sculpture, where the act of copulation is openly represented. The refinement of form in this carving suggests a debt to Brancusi. And in opposition to all those sculptors who had forsaken any direct manual contact with stone or marble, Epstein here asserts his prime commitment to the notion of respecting the block itself.

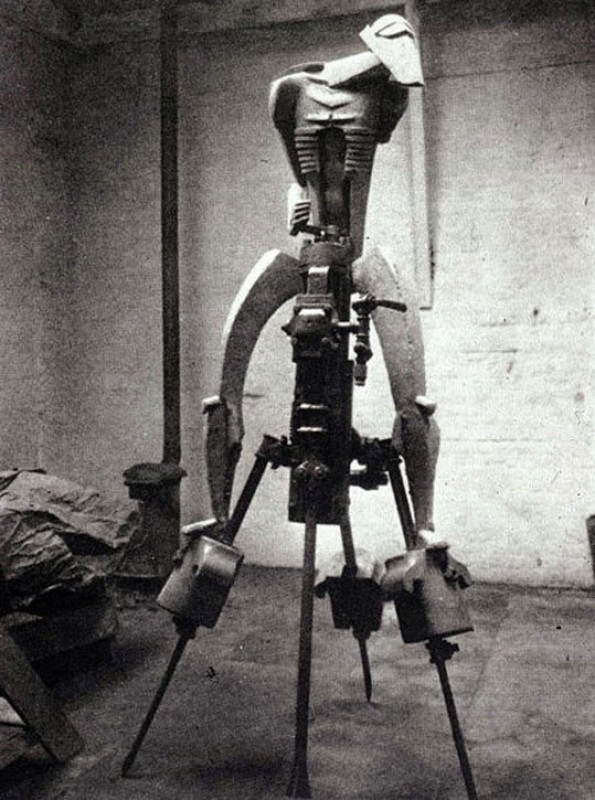

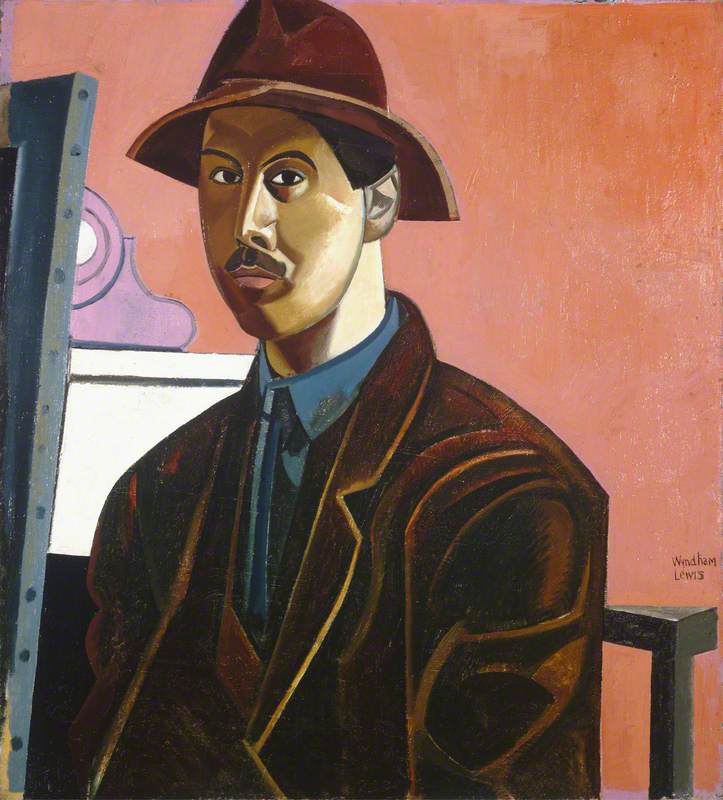

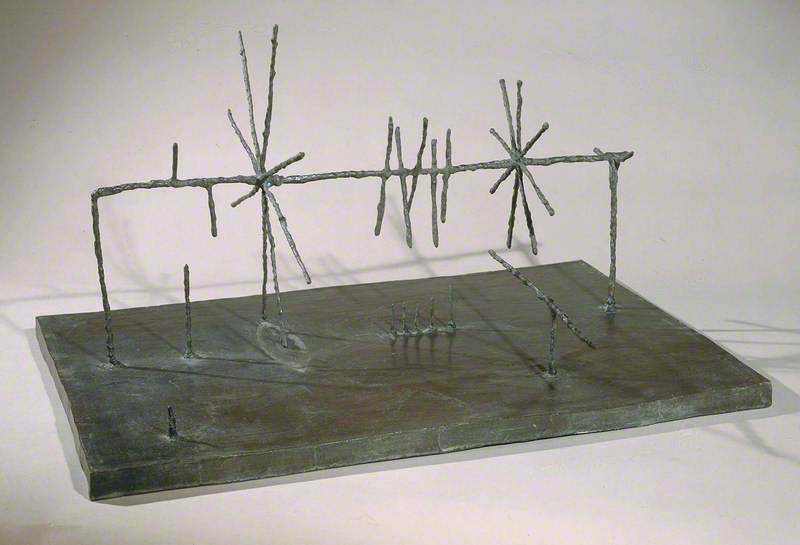

Even so, Epstein's art always confounds neat classification. Between 1913 and 1915, at the height of his most experimental phase, extreme simplification did not wholly satisfy the urge he felt to pursue a far more figurative involvement with portraiture. And Rock Drill, his most ambitious, astounding and thoroughly meditated work of this period, belongs within the orbit of the Vorticist movement.

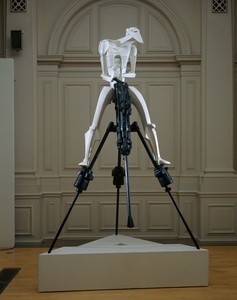

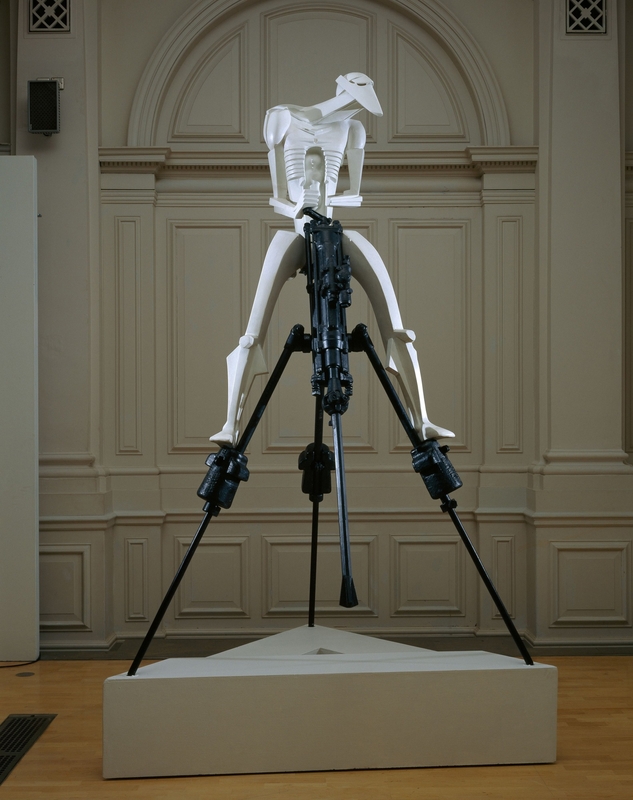

Indeed, the different stages of this wholly revolutionary sculpture summarise the concerns of the artists who contributed to the Vorticist magazine BLAST. The first stage of Epstein's Rock Drill project, defined in an extensive sequence of forceful drawings now in the Tate collection, proposes a view of the modern machine age compatible with the Vorticist manifestos. The driller bestrides his machine with superhuman confidence, wielding the phallic power of the drill in order to help construct the challenging new order of twentieth-century society.

By the time Epstein took the rule-breaking decision to combine a man-made plaster figure of the driller with a real ready-made machine (purchased second-hand for the purpose), this virile confidence had given way to a more disturbing vision. Now that an embryo nestles within the driller's body, he seems oppressed by the responsibility involved in handling such an aggressive instrument. Although his semi-robotic body has taken on many of the attributes of the machine he controls, this armoured man looks vulnerable as well as defensive.

David Bomberg, who was a friend of Epstein's, remembered visiting the sculpture towards the end of 1913, and he subsequently described how the 'tense figure' was 'perched near the top of the tripod... operating the Drill as if it were a machine gun, a prophetic symbol, I thought later of the impending war.'

This original version of Rock Drill was exhibited at the London Group show in 1915, and Epstein's rebellious decision to incorporate a real machine in his sculpture attracted the same kind of angry derision that Marcel Duchamp received when he displayed his ready-made art. Nobody wanted to acquire Rock Drill, and Epstein never showed it anywhere again. But he did receive support from T. E. Hulme, an enlightened critic who was planning to write a book on Epstein's work.

Even though he did not sign the manifesto in BLAST magazine, Epstein allowed two drawings to be reproduced in its pages. He also told Ezra Pound that Wyndham Lewis's drawings had 'the qualities of sculpture', and Epstein certainly gave his driller an automaton-like character closely related to Lewis's figures of the same period.

The story of Jacob Epstein's Rock Drill. See a rare photo of Rock Drill in #TheBodyExtended https://t.co/ZAIsQWPJiZ pic.twitter.com/sHFsZIjceg

— HenryMooreInstitute (@HMILeeds) August 5, 2016

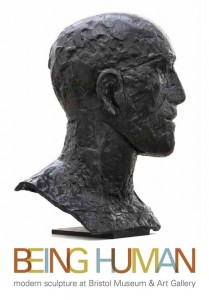

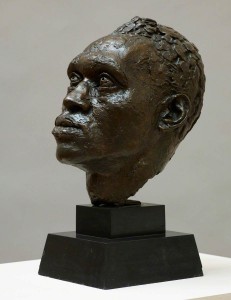

In other respects, however, Epstein was as fiercely independent of Vorticism as Bomberg. Soon after Henri Gaudier-Brzeska met his tragic death in the First World War, Hulme was also killed in combat. Their loss helped to persuade Epstein that the machine should be taken away from Rock Drill, thereby giving its remaining bronze torso a tragic helplessness it had not possessed before.

Deprived of his rearing machine, and suffering from severely dismembered arms, this visor-headed man is now more like a victim than a triumphant exemplar of industrial prowess. Epstein first displayed his anxious torso in 1916, when the war had already claimed an appalling number of lives and threatened to continue for an indefinite period. Unavoidably aware of this disaster, Epstein gave his haunted bronze the fearful and amputated identity of a wounded soldier returning in dejection from the Front.

© the Jacob Epstein estate / Tate Images. Image credit: Birmingham Museums Trust

Rock Drill (reconstruction after the original) 1913/1974

Jacob Epstein (1880–1959) (reproduction of) and Ann Christopher (b.1947) and Ken Cook (b.1944)

Birmingham Museums TrustBut several decades later, the first version of Rock Drill was successfully reconstructed by Ann Christopher and Ken Cook, making us realise how audacious Epstein had been when he created this arresting masterpiece just before the war's cataclysmic horrors assailed the world.

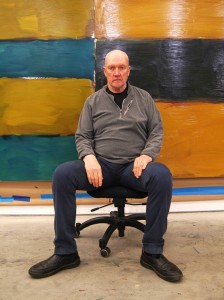

Richard Cork, art historian and author of Jacob Epstein (Tate Publishing, 1999)