It's easy enough to paint a fight, but how do you paint a disagreement?

A fight, after all, involves both parties simultaneously and intimately. They drive towards the centre of the picture to make something happen. An argument or a debate, by contrast, is a sequential affair (ideally at least). The participants take turns to make their point. Where a fight is a physical thing in the world, and (seductively for many artists) a dramatic physical thing, a disagreement is an abstraction, hanging in the air between combatants, who are likely to look, at any given moment, as if they are simply talking. Animatedly perhaps, furiously maybe, but talking nonetheless.

It's not impossible to capture disagreement, of course. Mark Perry, a photographer for the House of Commons Press Office, managed it on 19th December 2018, when indignant Conservative MPs and ministers protested at the Speaker's failure to rebuke Jeremy Corbyn for – allegedly – calling Theresa May a 'stupid woman'. The photograph he took was widely published and widely compared to fine art depictions of disputation and argument.

Today. pic.twitter.com/SqpZu2TwsT

— PARLY (@PARLYapp) December 19, 2018

The composition helped; a cluster of faces, varied in their bemusement, indignation and supplication, underlined by a frieze of five hands, which acted out the opposing positions. At one end John Bercow's left hand raised in a gesture which seems to be calling for a halt; at the other a parliamentarian's right hand, apparently directing the Speaker's attention to the hard evidence he's wilfully ignoring (and, as it happens, echoing the gesture of one of the figures in Raphael's Disputation of the Holy Sacrament in the Vatican).

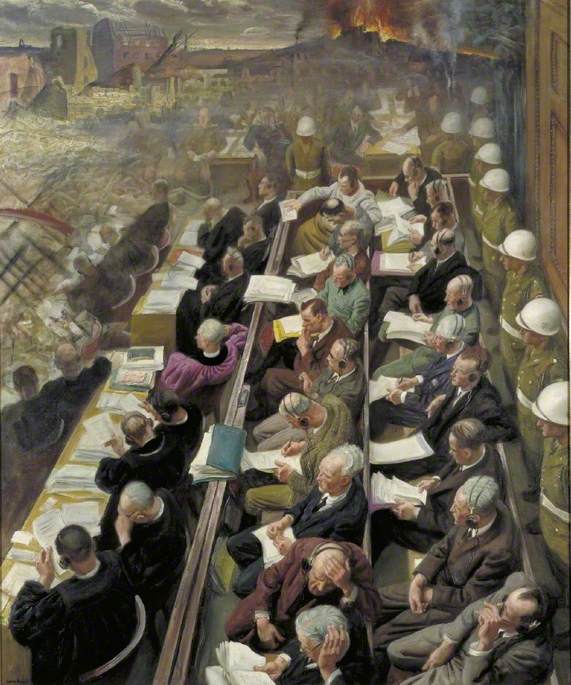

What's a little odd is how rare such images of legislative face-off are in paint. Search through the 650-plus artworks in the Parliamentary Art Collection and you'll find only a handful that actually capture the House in session, even fewer that capture it at a moment of drama.

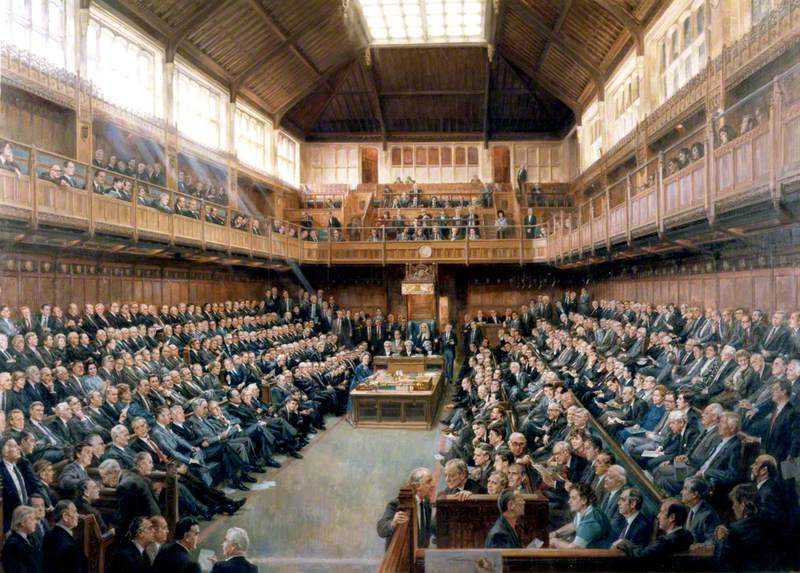

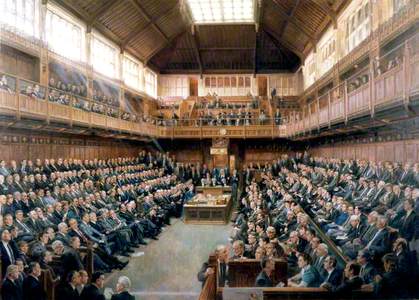

What you mostly get are portfolio portraits – such as June Mendoza's The House of Commons, 1986, or Leopold Braun's House of Commons, 1914 – the sort of paintings which come with numbered outline drawings as an accompaniment, so you can identify who that actually is six seats along on the second row from the back.

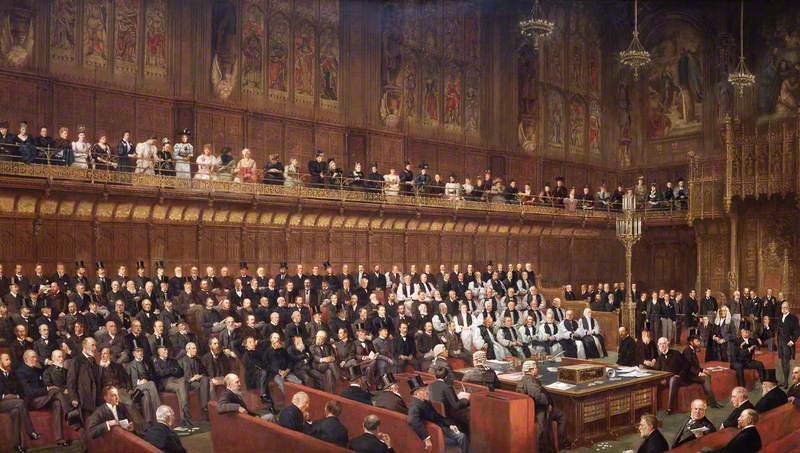

There are a few attempts at crucial legislative moments – Dickinson and Foster's The Home Rule Debate in The House of Lords, 1893, Lord Chancellor about to Put the Question, for example – but they're pretty dull affairs, essentially Hansard without the exciting bits, which is what was actually said.

The Home Rule Debate in House of Lords, 1893, Lord Chancellor about to Put the Question

Dickinson (active 1890–1910) and Foster (active 1890–1910)

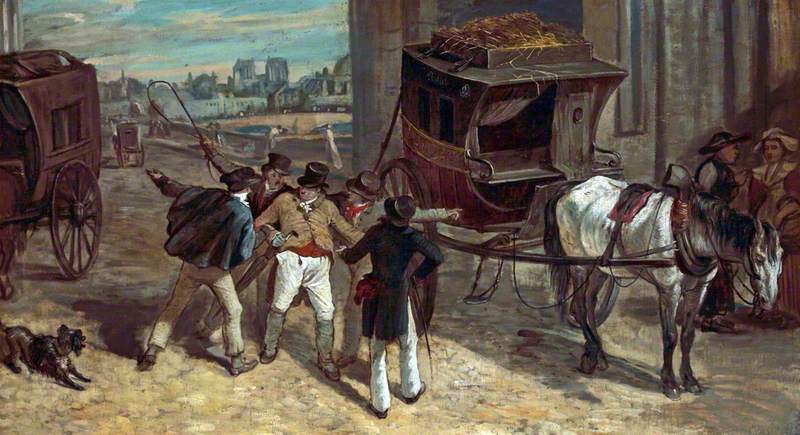

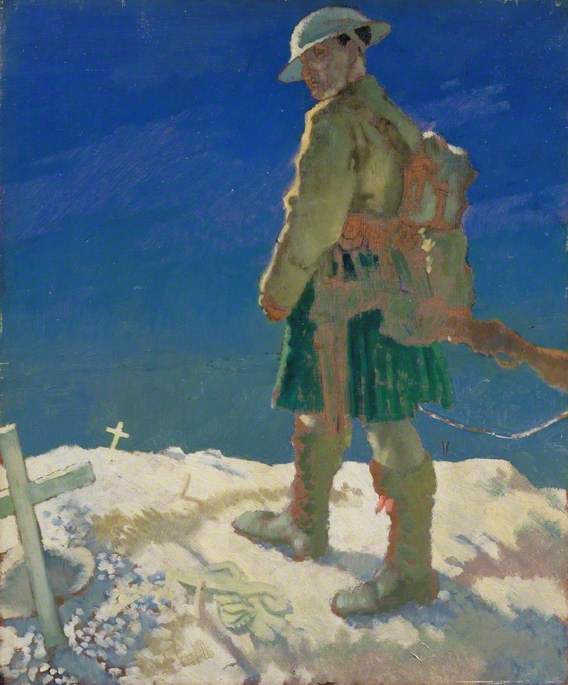

There seem to be only two paintings in the Parliamentary Art Collection that attempt to capture the heat of historical disagreement, neither of them exactly representative. One is, strictly speaking, a fight: Andrew Carrick Gow's painting of Speaker Finch being held down by Denzil Holles and Benjamin Valentine after he'd attempted to adjourn the House in 1629 at Charles I's request. Argument has failed here and been replaced by brute force.

House of Commons, 1628–1629, Speaker Finch Held by Holles and Valentine

1912

Andrew Carrick Gow (1848–1920)

The other is George Cruickshank's picture John Bright and W. A. Mackinnon in the Debates on Franchise Reform, an image which marries collective portraiture with a cartoonist's short cut.

John Bright and W. A. Mackinnon in the Debates on Franchise Reform

1860

George Cruikshank (1792–1878)

John Bright, champion of reform (and coiner of that phrase about 'the Mother of Parliaments'), stands at one side of the Despatch Box, while Mackinnon, who opposed the enlargement of the franchise, is shown, gathering a fizzing mortar labelled 'Reform bomb' like a fly-half receiving a pass and deftly guiding it onwards through a nearby window, where it can explode harmlessly – or at least only at the cost of a few working men who can't vote anyway.

That trail of smoke does hint at the way one speaker's words can be caught and diverted in another direction – but Cruickshank is leaning on the scales here, Mackinnon's hands implying that the right direction of travel can be one way only. You have to leave the Parliamentary collection to find a painting in which he did much better at capturing the reciprocal tug of argument, the kind of stalled intransigence which we're currently experiencing as the House of Commons debates Brexit.

The Rival Touts (John Bull in a Fix) depicts the figure of John Bull surrounded by hackney cab drivers trying to drum up a bit of business; one points to the left, one to the right and a third to the middle distance.

Bull is surrounded and, like the weary horse to the right of the picture, going nowhere. Should Parliamentarians want an image of their current stalemate they could do a lot worse than this.

But they could do better too. At least if they're prepared to acknowledge that there might always be a bit of give in an argumentative position – that one person's steadfast resolution is another's pig-headedness. The neatest visual distillation of intractable disagreement I found browsing through Art UK can be found in York Art Gallery. It's by a painter of the Italian Baroque, Domenico Fetti, and it's titled The Parable of the Mote and the Beam.

Hands are central here too, just as they were in Mark Perry's accidental Old Master, pointing fingers directly opposed to represent opposing points of view. And points of view is the pertinent phrase, since the two figures seen at odds in the foreground are linked by a splintered timber in the background which appears, by the foreshortening of perspective, to threaten both their eyesight.

They are (reasonably enough since it isn't actually in their eyeline) unaware of the apparent hazard. But the picture's viewer, standing off to the side of the argument, sees what neither of them can see; their kinship in single-mindedness. Paradoxically all they can see is the other's pointing finger, and not what it's pointing to.

It should hang in the Division Lobby.

Tom Sutcliffe, Arts broadcaster, BBC Radio 4