Artists and writers have been looking back to the ancient world for hundreds of years. The colourful stories have inspired countless works of art and literature, but these depictions have perhaps tended to show only a limited perspective on the mythology. Of the translations, art, poetry and literature we're most familiar with, the creators tend to be pretty un-diverse – being largely white, male and typically middle class. The works accentuated the heroic and powerful while downplaying other elements of ancient Greek society such as homosexuality, gender imbalances and slavery.

In some ways, this reflects the patriarchal society of ancient Greece, where women typically didn't seem to have had many rights – they weren't able to own property, vote or inherit

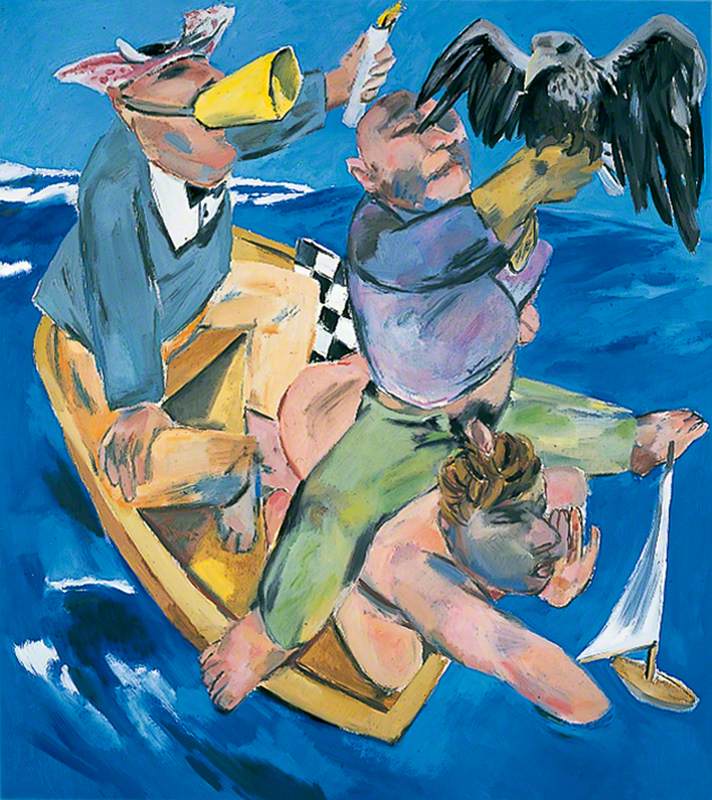

Take Circe the witch, for example. When Odysseus and his crew wash up on her island, she uses her seductive charms and magical powers to outwit most of the men – turning them into pigs – but her attempts to overcome Odysseus are foiled by a tip-off from the god Hermes. She subjects herself to Odysseus's will, turning the crew back to humans and hosting them all for nearly a year. Circe bears his child before he leaves, homeward bound (or so he thinks) back to his wife and family in Ithaca. She's typically portrayed as mysterious, manipulative and is often thought to act as a warning to men against the dangers of seductive women.

In John William Waterhouse's painting Circe at Gallery Oldham, she's shown with a placid, welcoming expression and in a nearly transparent dress, offering a cup of wine to her guest Odysseus (seen in the mirror). Viewers familiar with the poem will know that Odysseus needs to be careful! The wine is laced with a magic potion, the results of which can be seen at her feet – one of Odysseus's crew turned into a pig. 'Beware of seductive women' is the clear message here.

Penelope with the Suitors

about 1509

Bernardino Pinturicchio (c.1454–1513)

Or take Odysseus's wife, Penelope, who patiently and loyally waits for 20 years for her husband to return home from the Trojan wars. Her agency is limited to stoically enduring the difficulties of having an absent husband/king, forced to put up with the suitors vying to take Odysseus's place. She's often celebrated for her chasteness and loyalty to her husband. She spends the two decades at home rejecting the advances of other

In this painting by

This gender imbalance plays out in many stories from the ancient world and reflects the patriarchal society which produced them. Slavery, too, played a major part in the economy of the ancient Greeks. In the Iliad, Briseis – the former queen of a conquered city – is treated as a possession who can be passed from one owner to the next.

In this George Frederick Watts painting, she's shown being led away from one master, Achilles, to her new owner, Agamemnon. The artist portrays Briseis looking back at Achilles longingly. Watts is more concerned about the romantic tragedy and ignores the fact that Achilles actually owns Briseis and was probably more upset about being publicly disrespected by Agamemnon than losing his concubine.

The versions of the stories which we have received, translations from Greek, Latin, Arabic, Hebrew and then into English and other modern languages have recurring themes of treating women and other social groups poorly. These patriarchal societies interpreted the stories from their own perspectives and produced works which showed women and other peoples as inferior and propagated values of 'otherness'. By heralding figures from classical mythology, artists and writers from the Renaissance onwards gave justification to the violent acts being committed on those 'lesser' or 'other' in their own times. Europe was going through huge changes, developing empires, conquering and enslaving other peoples – much as the Greeks and Romans did.

The Judgement of Paris

c.1450–1455

Master of the Judgement of Paris (active mid-15th C)

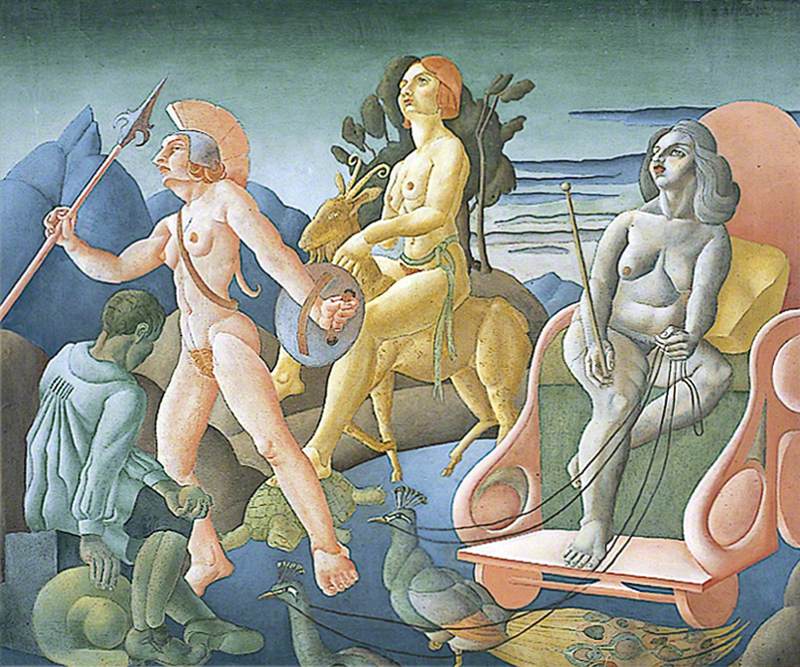

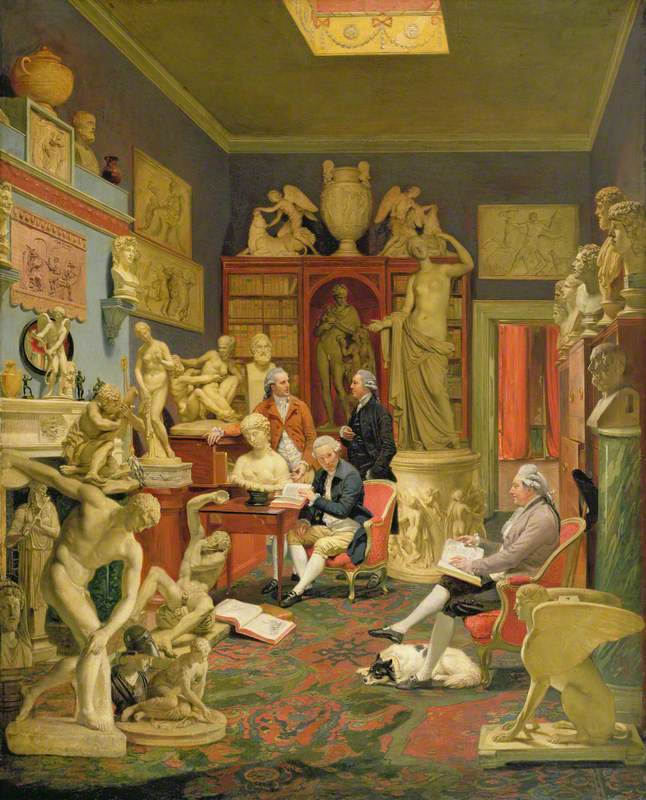

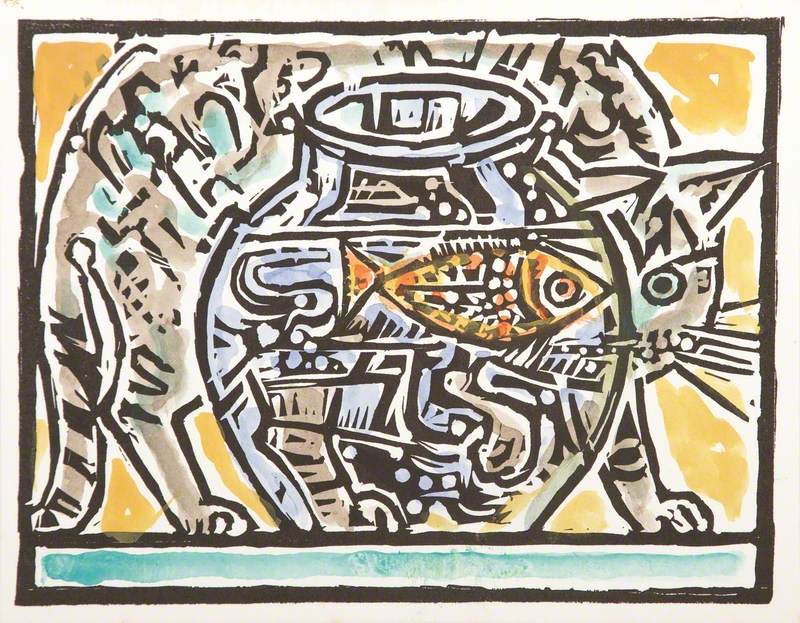

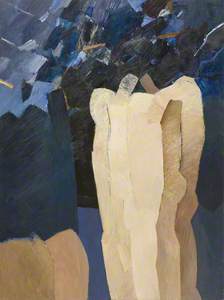

There are, however, some voices which question the traditional representation of the Greek myths. Artists like Ithell Colquhoun have also been drawn to the rich and fascinating ancient Greek world but have chosen to show it in a different way. If you compare her painting The Judgment of Paris with a fifteenth-century example from The Burrell Collection on the same topic, you can see that in Colquhoun's version the three goddesses – Athena, Aphrodite and Hera – are presented in all their divine glory with Paris, who sits head bowed and humbled. The power dynamic in the work by the Master of the Judgement of Paris, on the other hand, is quite different. Here the three goddesses are meek and vulnerable in front of a mere mortal such as Paris. Colquhoun's are much more muscular, powerful and

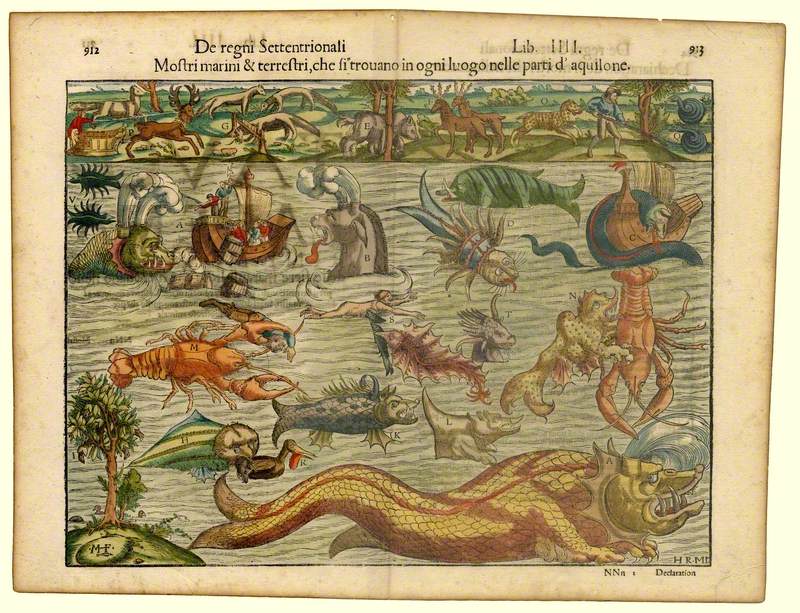

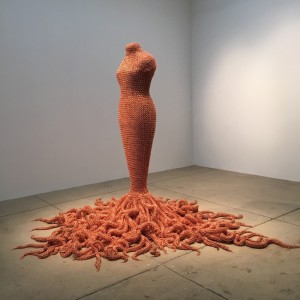

Her Scylla too represents a figure from antiquity. In the Odyssey, Scylla is a ferocious sea monster who prowls a narrow cliff-sided strait, pouncing on unwary sailors and eating them whole. Colquhoun's version becomes almost a

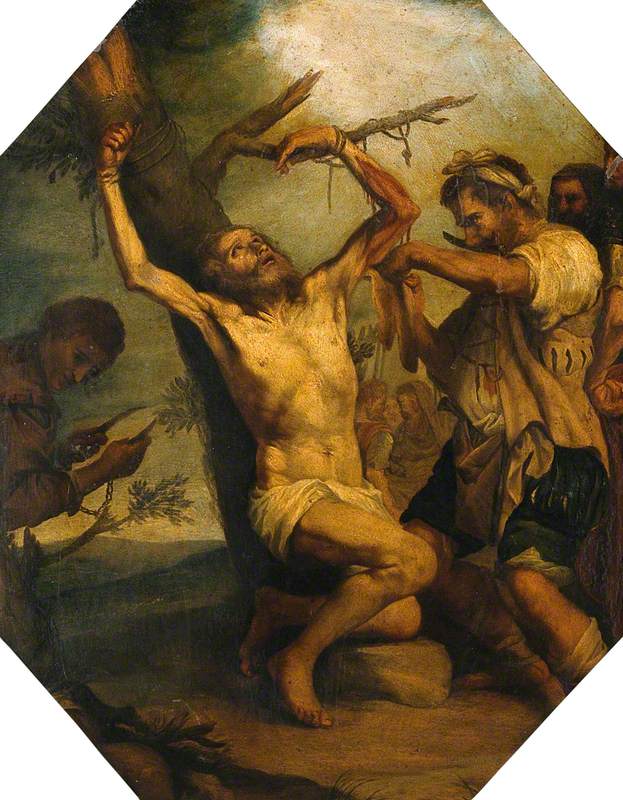

Elisabeth Frink's '

Lubaina Himid's painting Hannibal's Sister draws attention to the lack of representations of both powerful women and people of colour from art depicting the classical world. The Greeks and Romans were Mediterranean powers after all, with North Africa just being a boat ride away. People of colour were certainly present in the stories – the Egyptians, Ethiopians and Carthaginians being obvious examples – but why are so few represented in the art produced to depict this mythology?

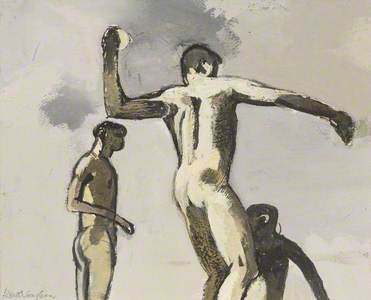

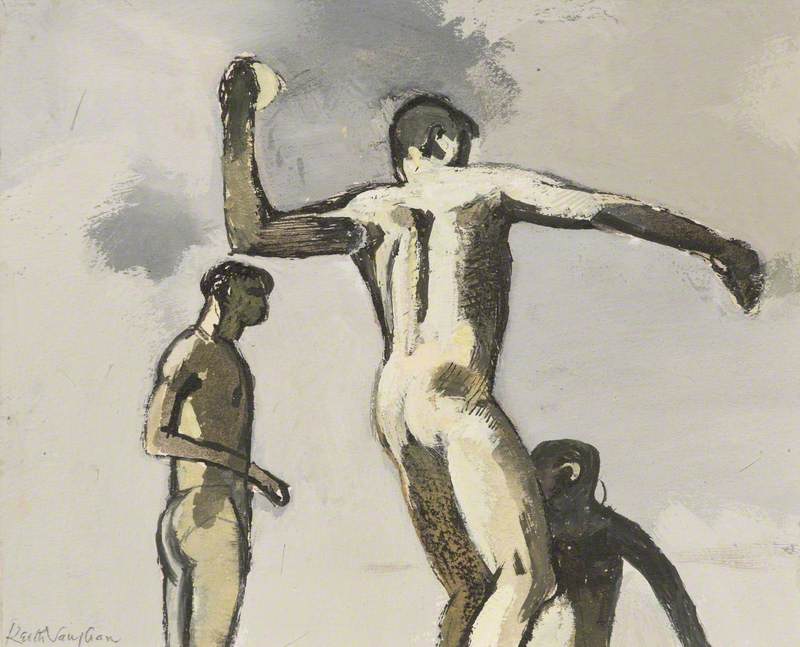

Figure Throwing at a Wave

1950

John Keith Vaughan (1912–1977)

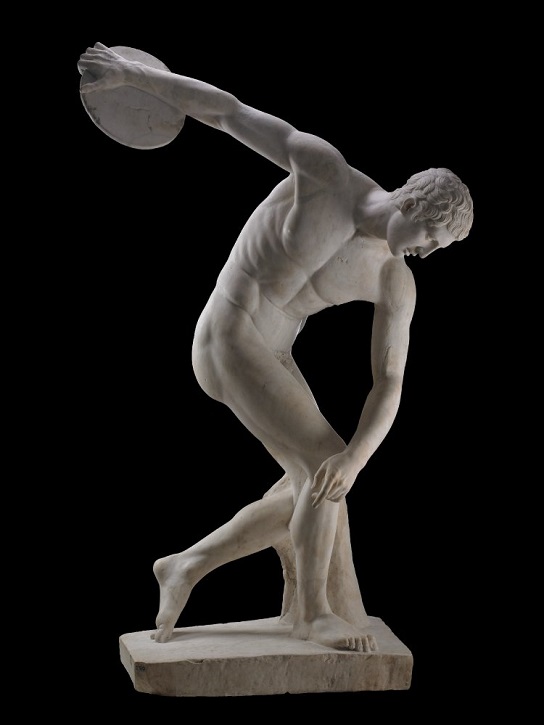

The Townley Discobolus

2nd century AD marble copy of a 1st century BC bronze original by Myron

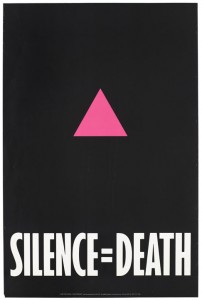

Whilst same-sex relationships have been present in the Greek myths (see Achilles and Patroclus, or Apollo and Cyparissus), artworks and translations often skipped over the nature of these relationships. Pylades becomes Orestes' 'friend' or the erotic nature of Zeus' infatuation with Ganymede was omitted. Many gay male artists have reclaimed stories from ancient Greece and Rome, highlighting how same-sex relationships were visible and respected in ancient Greece. Keith Vaughan's depictions of naked men have a clear heritage in the athletic sculpture of Greece and Rome. In his humorous and erotic drawing Minotaur and Man, the Minotaur, often seen as a symbol of male sexuality, is shown in the middle of an act that men in the ancient Greek world would have probably been very familiar with.

The Strangford Apollo

490 BC, marble by Greek School

Perhaps the art made by Colquhoun, Frink,

Iain Calderwood, Image Officer at Art UK