The year 1923 found Stanley Spencer developing ideas for his most ambitious painting to date: his Resurrection, Cookham. In the finished work, Spencer's first wife, Hilda Carline, is depicted three times.

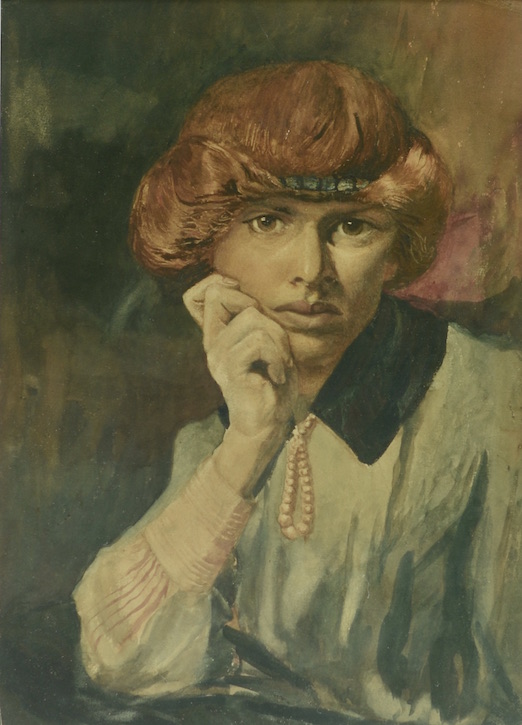

Throughout his life, Spencer repeatedly painted Carline. She has become familiar to us as Spencer's first wife and muse, the mother of his children, and as a participant in 'the most bizarre domestic soap opera in the history of British art' when Spencer, infatuated with Patricia Preece (with whom he never lived) divorced Carline. Reference is rarely made to Carline's own considerable achievement as an artist but as Spencer began work on his monumental Resurrection, Carline was painting her own magnificent self portrait now in the Tate Britain collection.

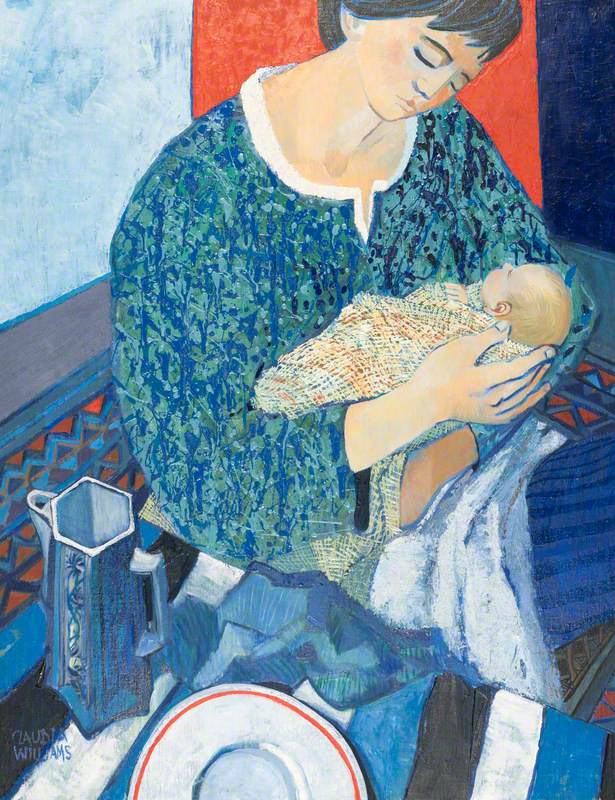

In this self portrait, Carline appraised herself with a penetrating intensity. The sumptuous choice of colour and sensitive modelling display her ability as a skilled portraitist.

Hilda Carline was born in 1889, the only girl among five children. She grew up in Oxford, surrounded by the paintings of her father George Carline, then a highly regarded and financially successful painter who regularly exhibited at the Royal Academy. He encouraged and nurtured his daughter's evident talent from an early age, along with the skills of her brothers Sydney and Richard.

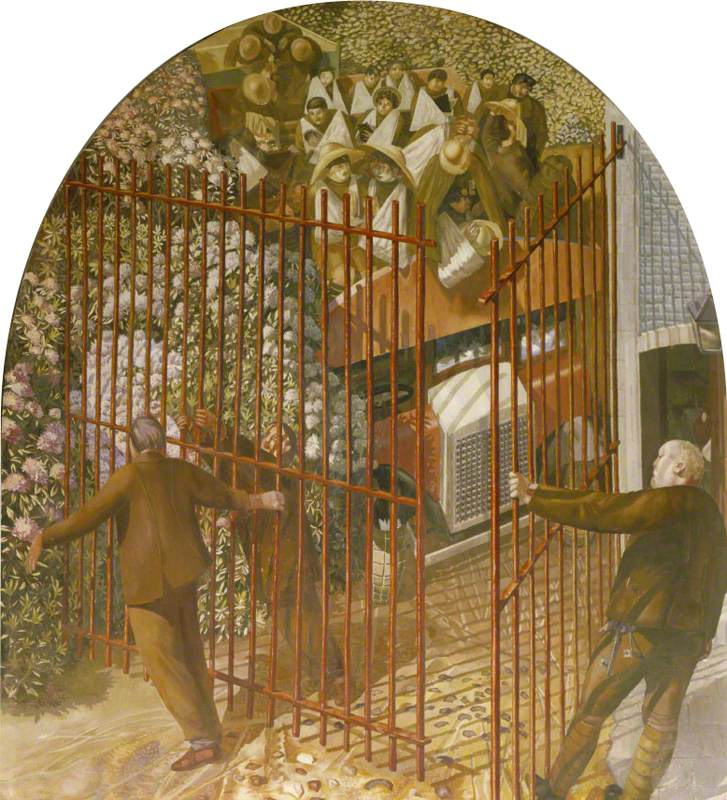

The Organ Grinder

c.1910, watercolour on paper by Hilda Anne Carline (1889–1950). Private collection

The Royal Drawing Society, in 1907, awarded Carline a special Certificate of Honour for the rare achievement of gaining Honours in all six divisions of the Society's examinations. Despite this, Carline's father baulked at his daughter's wish in the following year to follow her brother Sydney to the Slade School of Fine Art in London. In 1913, at the age of 24, Carline finally got her wish for a formal art training and joined her brothers Sydney and Richard at the short-lived Hampstead studio run by the Canadian-born, Paris-trained Percyval Tudor-Hart.

Self Portrait

1913, watercolour on paper by Hilda Anne Carline (1889–1950). Private collection

When Carline joined Tudor-Hart's studio she was already a highly skilled draughtswoman and watercolourist albeit constrained by the tightly controlled naturalism that her father had taught her – as is evident in The Organ Grinder (above) and her 1913 self portrait. Tudor-Hart introduced Carline to contemporary modernist modes of expression. From him, she became aware of Post-Impressionism and the colour theories of Kandinsky.

Hilda Carline's painting of a zeppelin was made in 1914 and records a live event as an airship flew directly over and then encircled the Carline home at 47 Downshire Hill, Hampstead in London. pic.twitter.com/V6tE4RR5RK

— Richard Morris: Art History in a Tweet (@ahistoryinart) January 31, 2022

The impact of this new awareness on Carline's work was immediate, resulting in a bold simplification of design and a more expressive use of colour as is exemplified in the menacing Zeppelin over London, with its ball of blazing light hanging low in the night sky.

'Cliffs at Seaford,' (1920) shows why Hilda Carline was an important figure in the development of British modernism before and between the wars, for both the company she kept and the work she produced. She married Stanley Spencer in 1925. pic.twitter.com/QqVd2ZckQo

— Richard Morris: Art History in a Tweet (@ahistoryinart) November 3, 2022

Tudor Hart's influence on Carline's work lingered for many years; inspiring works such as the striking seascape Cliffs, Seaford (1920) with its unusual perspective from precipitous chalk cliffs over sea and sand below.

In 1921 Carline painted Melancholy in a Country Garden. The lone figure standing amidst the luxuriant abundance of the summer garden, gazing through the open gate to the sunlit fields beyond is Carline's mother. This deeply expressive painting reflects both Carline's and her mother's grief at the sudden death of her father the previous year.

Melancholy in a Country Garden

1921, oil on canvas by Hilda Anne Carline (1889–1950). Private collection

In the early 1920s the Carline siblings, Hilda, Sydney and Richard were all based at the new family home of 47 Downshire Hill, Hampstead. They regarded themselves as 'adherents of the modern movement', and attracted around themselves a wide circle of leading artistic and literary figures including Henry Lamb, Mark Gertler, Paul and John Nash, Christopher Nevinson and Stanley and Gilbert Spencer. Many of these artists, including occasionally Hilda, exhibited their work with the progressive London Group.

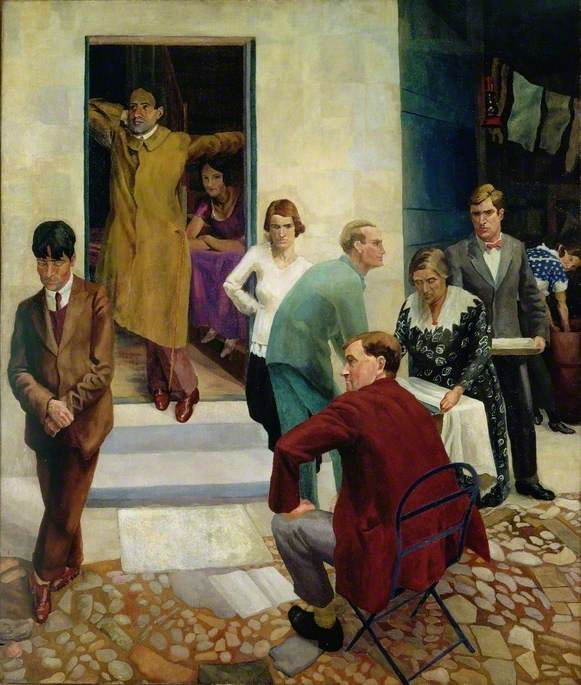

Gathering on the Terrace at 47 Downshire Hill, Hampstead, London

c.1924

Richard Carline (1896–1980)

Richard Carline has immortalised some of the core members of this artistic circle in his Gathering on the Terrace. Hilda Carline and Stanley Spencer stand on either side of the open doorway in which James Wood stands. Carline's mother, her brother Sydney and friends Henry Lamb, Richard Hartley and Kate Foster are the others depicted in this contemporary conversation piece.

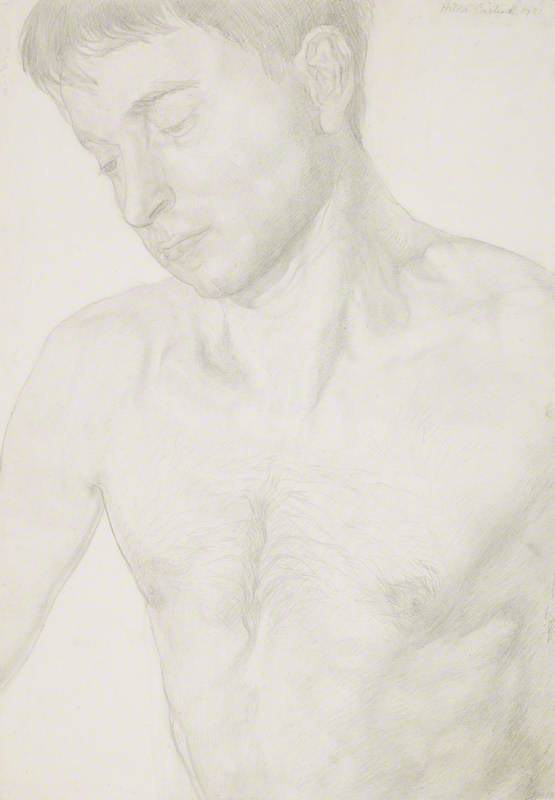

As the 1920s progressed, a strand of naturalism reasserted itself in Carline's work. This was undoubtedly the result of Carline's part-time attendance at the Slade School of Art between 1919 and 1923. With its emphasis on analytical drawing, the Slade rekindled Carline's interest in the human figure. The acuteness of her observational skills is evident in the series of keenly observed portraits that she made during this period, including her 1923 self portrait (above), and those of Gilbert and Stanley Spencer.

Carline met fellow student Gilbert Spencer at the Slade. A romantic relationship was developing with Gilbert until she met his brother Stanley who was immediately attracted to her. On a summer's day in 1920, Gilbert escorted Carline to the Spencer home in Cookham, Berkshire where Carline was asked to state her preferred of the two brothers. She chose Stanley.

Three years later, Carline painted Stanley's portrait (private collection). Compared with her drawing of Gilbert, this portrait is more diffident: Carline paints Stanley with his head tilted to one side, his gaze averted. Spencer was apparently intrigued by the composition. When he painted a self portrait that same year, he abandoned his habitual full-face pose for one that is an intriguing echo of Carline's. In fact, it seems that, in the 1920s, when Carline painted or even suggested a subject, Spencer would often also take it up. Both artists, for example, produced similar compositions depicting the wooden minaret in Sarajevo.

The Wooden Minaret, Sarajevo

1922, oil on canvas by Hilda Anne Carline (1889–1950). Private collection

Carline and Stanley married in February 1925 at Wangford in Suffolk. Their honeymoon was, in effect, a painting holiday during which Carline produced Smoke from the Southwold Train. The unusual elongated format that Carline adopted for this painting enabled her to produce a particularly engaging expansive landscape.

Smoke from the Southwold Train

1925, oil on canvas by Hilda Anne Carline (1889–1950). Private collection

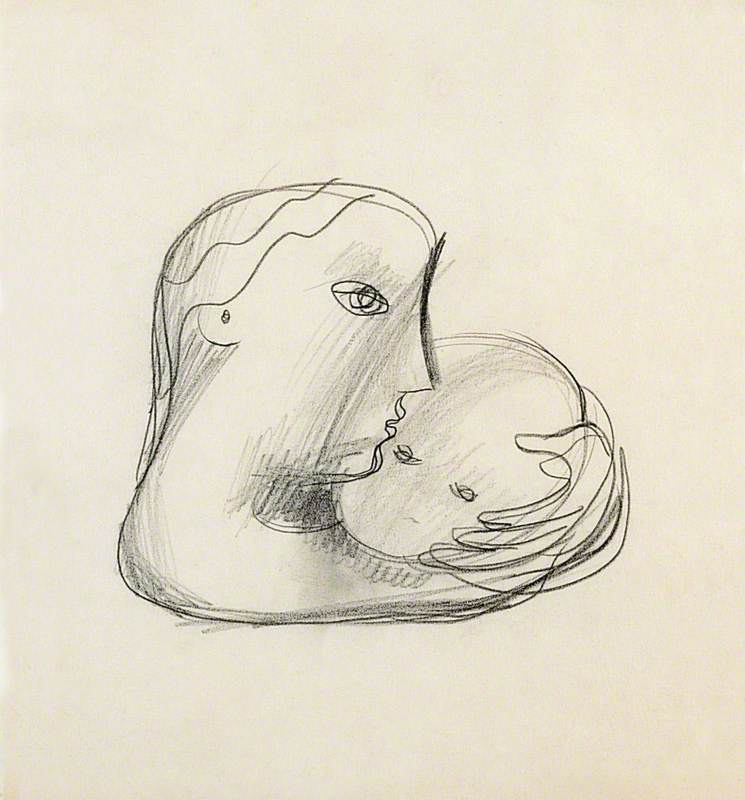

Neither Spencer nor Carline were prepared for the different tempo of life that marriage and the arrival of children would bring. Their daughters Shirin and Unity were born in November 1925 and May 1930. Although Spencer was always a genuine admirer of his wife's work, he never fully acknowledged the problem, as experienced by many of Carline's female contemporaries, of how to continue with work whilst coping with the demands of domesticity.

Periods of dispute, separation and reconciliation were the inevitable result before the permanent end of their marriage in 1937. Nevertheless, some of Carline's most powerful and perceptive portraits date from this difficult period, for example, those of the Spencers' maid Elsie and of her rival for Spencer's affections, Patricia Preece.

In 1929, after four years of peripatetic existence between London and Burghclere, Spencer and Carline finally moved into a permanent home (in Burghclere) and employed a maid, Elsie Munday. Carline's full-length painting of Elsie, dressed in her best clothes could be understood as being a tribute to the person who made Carline's life as an artist possible again by relieving her of many domestic responsibilities.

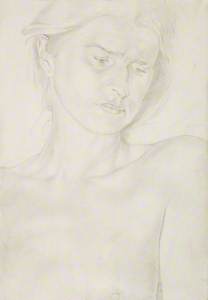

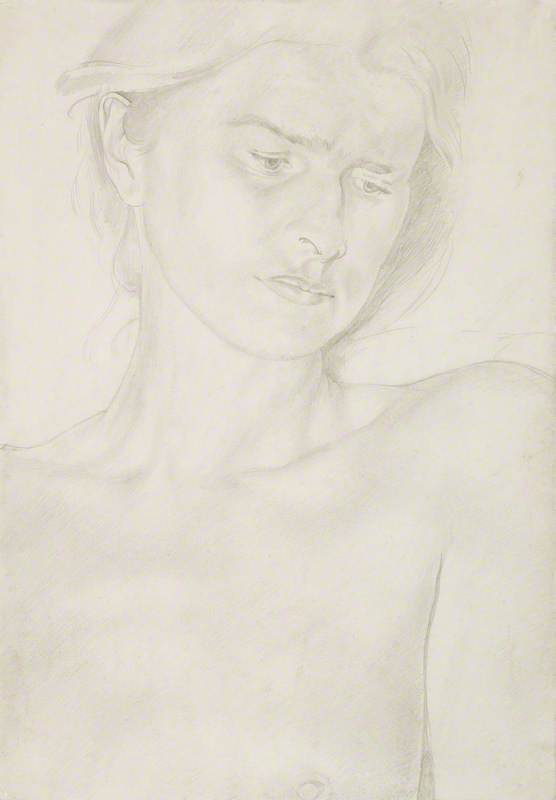

Hilda Spencer (née Carline) (1889–1950)

1931

Stanley Spencer (1891–1959)

During one brief reconciliation in 1931, Carline and Stanley produced an intimate pair of drawings of each other. The delicacy of these celebrates an abiding tenderness and love between the couple, as is emphasised by their nudity.

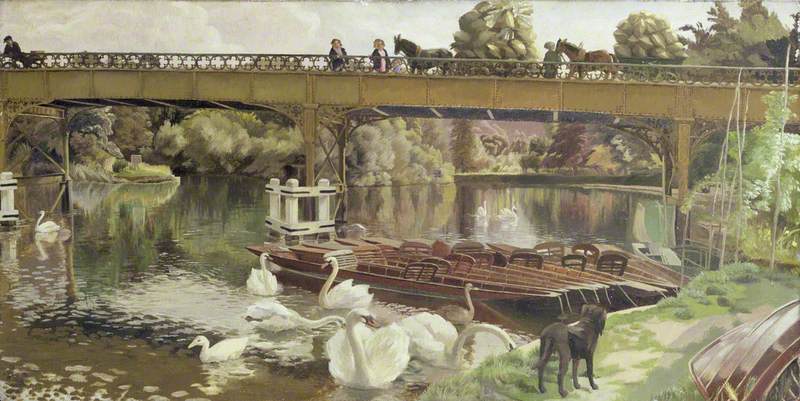

A similar sensitivity is also evident in Carline's painting of Swans, Cookham Bridge, in which she communicates her experience of a tranquil summer's day.

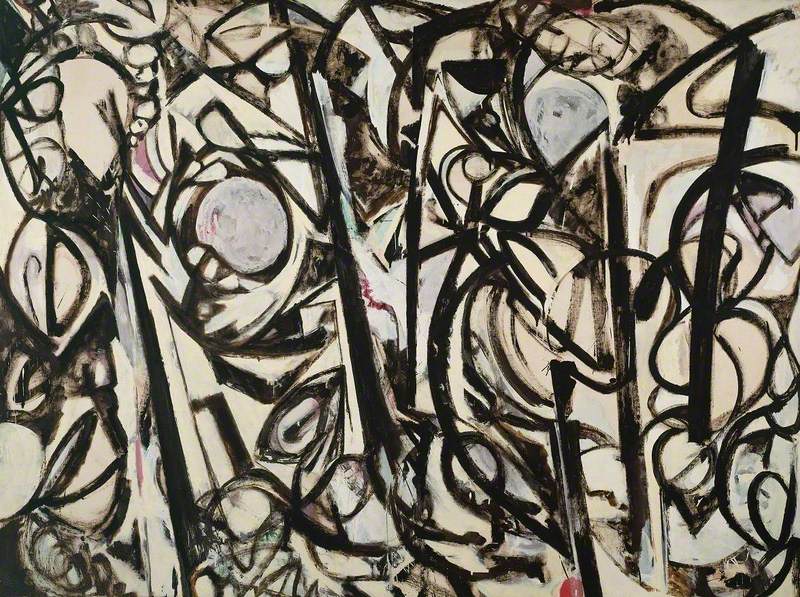

In 1942 Carline tragically suffered a mental collapse. As she recovered she found herself painting with a new freedom, producing some of her most imaginative compositions such as A Vision of God in Heaven. In this dramatic response to her abiding Christian faith, Carline's instinctive use of expressive colour reasserts itself with all the intensity of her Tudor-Hart student days.

A Vision of God in Heaven

1946, pastel on paper by Hilda Anne Carline (1889–1950). Private collection

Towards the end of the 1940s, Carline developed breast cancer, dying on 1st November 1950.

Carline's modesty, coupled with recurring crises of confidence in the merit of her work, resulted in her rarely exhibiting her work during her lifetime. Fortunately, though, a substantial body of her work survives (mainly in private collections), which was drawn upon for a 1999 touring retrospective of her work, and again for the exhibition 'Those Remarkable Carlines' at Burgh House, London, showing until April 2023. These exhibitions provided an opportunity to appreciate Carline's originality and contribution to British modernism.

Alison Thomas, freelance writer and curator