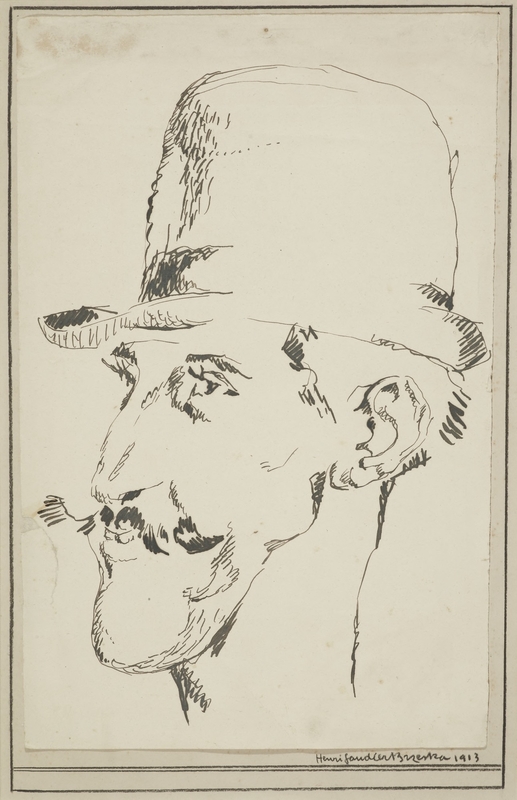

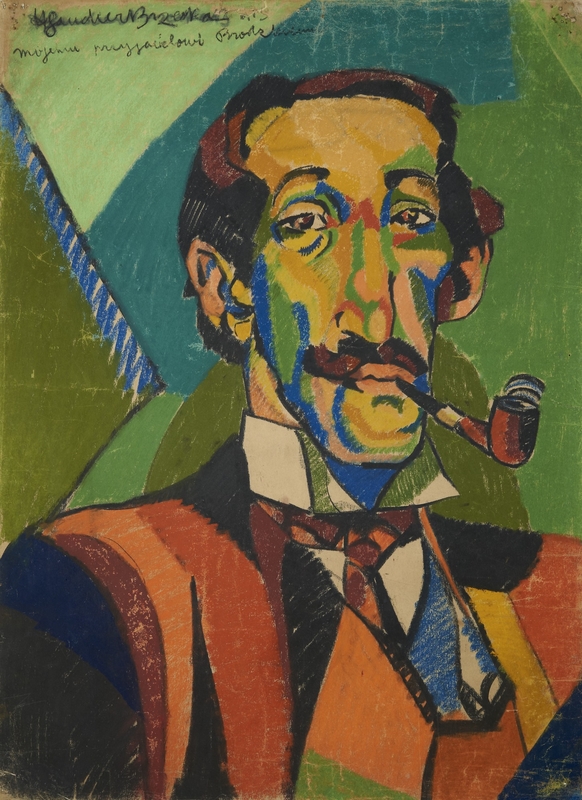

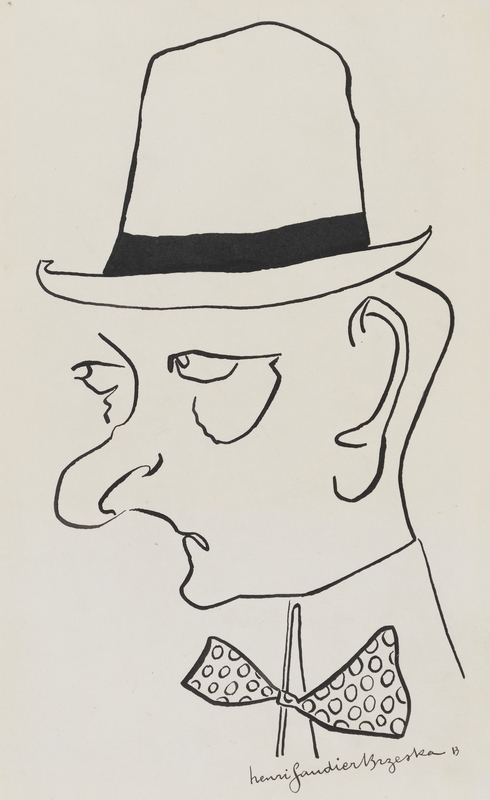

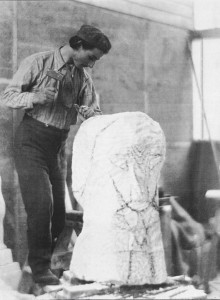

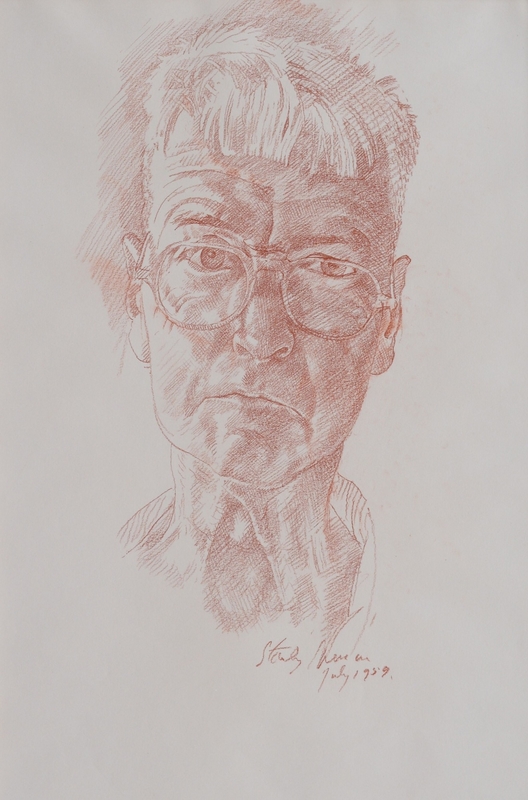

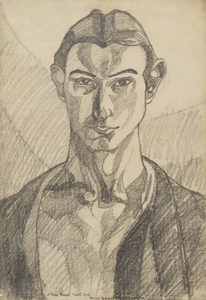

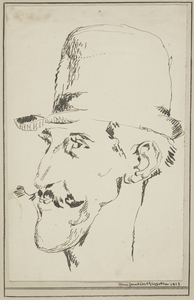

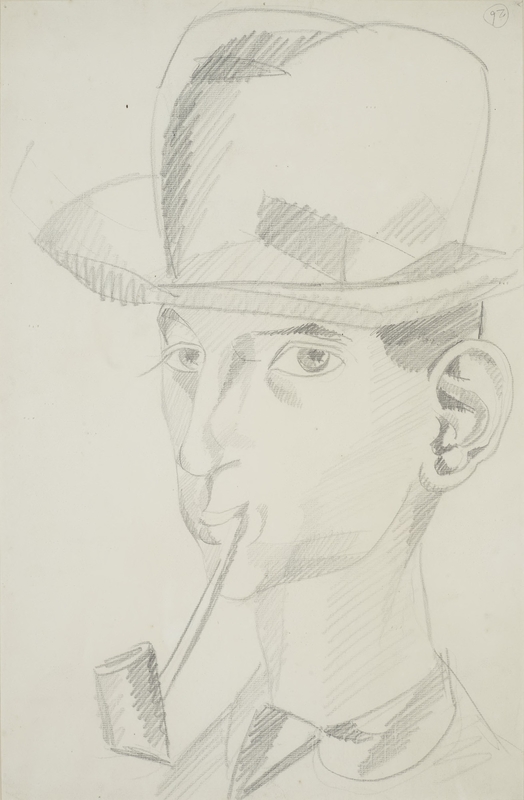

Do not be deceived by this playful self-portrait sketch by Henri Gaudier-Brzeska. Baby-faced and doe-eyed like one of his sculpted fawns, he looks out from under a bowler hat, his sidelong glance and pointed nose reaching towards us, while his smirking mouth is puckered around a pipe.

Self-Portrait with a Pipe (1)

1913

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska (1891–1915)

Usually known for his shabby attire and abominable personal hygiene, Gaudier-Brzeska stages himself as a caricature of the preening bourgeois artist, aiming an ironic jibe at his contemporary painters and sculptors. He seems to say, 'what fools we look when we dress ourselves up for polite society to try and win a commission or court a client!'

The drawing is the first of three versions of this pose he sketched in 1913 as he began to experiment with a Cubist method of angular hatching and geometric abstraction. This approach would reach a more heroic tenor in the closely related pastel drawing of his friend Horace Brodzky. Taken on its own terms, the self-portrait is a light-hearted drawing, a jovial page torn from the kunstlerroman that was his life in pre-war London. Returned to its context, however, we find it surrounded by a more radical story of how politics guided this artist's approach to draughtsmanship and his refusal to conform to the social codes of Edwardian England.

A tendency toward satirical caricature in Gaudier-Brzeska's drawings can be traced back to his time in Paris between October 1909 and December 1910. He was a boisterous and fiercely intelligent 18-year-old who could speak German, Russian and English in addition to his native French, having spent periods studying art and commerce in Bristol, Cardiff, Nuremberg and Munich. Upon moving to the French capital he was quickly immersed in anti-authoritarian political networks and told a confidante back in Germany that 'I am an anarchist in my soul,' an ally 'of the producer, of the worker,' united in the fight against 'the fat-bellied, flabby faced plutocrat'. Later, he joined 'an antiparliamentary insurrectional committee, who have in view a revolution only possible by force.'

Perhaps the most significant factor in this robust political engagement was Gaudier-Brzeska's avid readership of two magazines associated with the anarchist-syndicalist writer and revolutionary Gustave Hervé: La Guerre Sociale and Les Hommes du Jour. Gaudier-Brzeska's first documented encounter with state violence was closely associated with La Guerre Sociale. On 1st July 1910, he responded to a call for support published by the magazine and attended a rally of the jeunesse revolutionnaire, the 'revolutionary youth', at La Sante prison. A large crowd gathered to prevent the execution of Jean-Jacques Liabeuf, a so-called 'apache' lionised by the anarchist press, who had killed a policeman and wounded six others in a vengeful defence of his honour after being charged with prostituting his girlfriend. As the protesters chanted 'Vive Liabeuf', the police ordered a cavalry charge, gunshots were heard and chaos ensued. Gaudier-Brzeska managed to slip away unharmed.

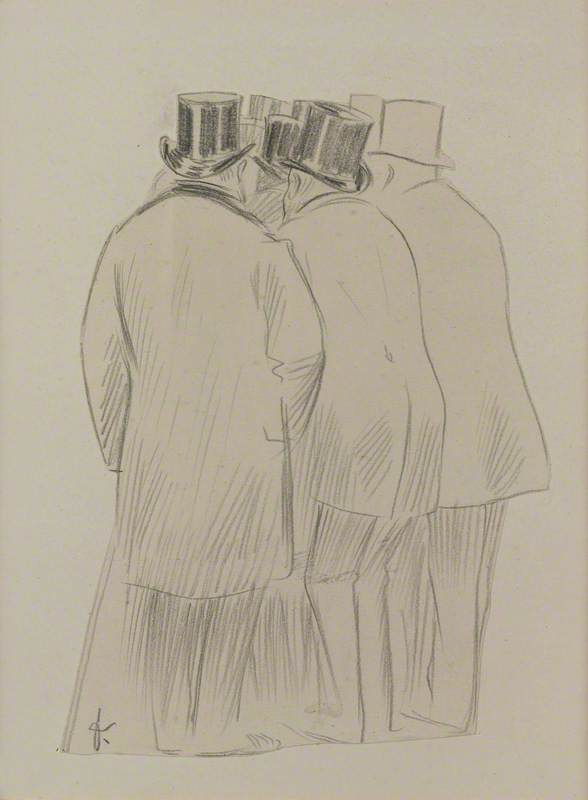

These explicitly anarchist publications featured political illustrations by artists such as Jules Félix Grandjouan and Aristide Delannoy, whose firm elasticity of line was combined with subjects that expressed bitter opposition to the militarism and colonialism of the French state. Gaudier-Brzeska similarly admired the political work of Théophile Steinlen, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Jean-Louis Forain. Following their example and a rich lineage of French satirical sketches, he too began to poke fun at authority figures in his drawings.

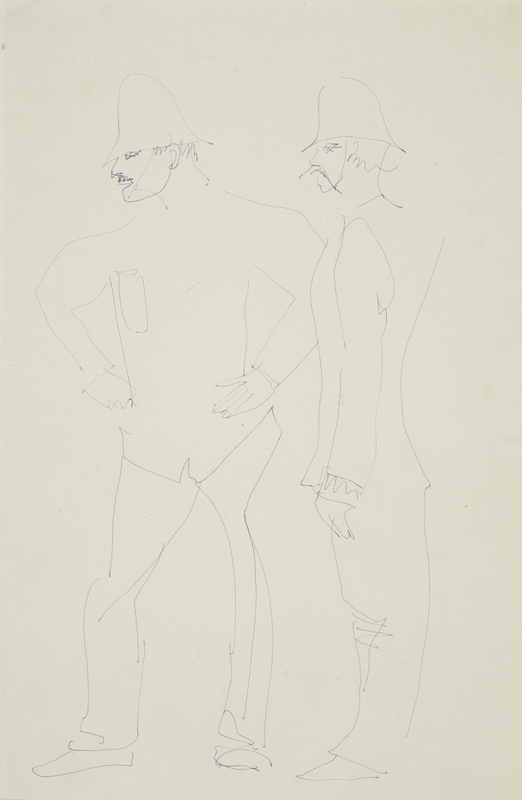

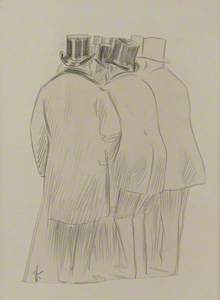

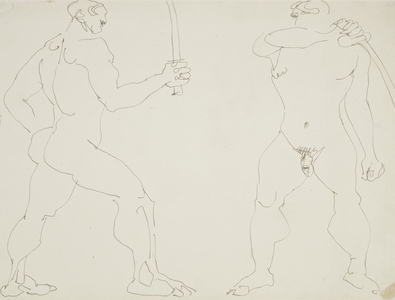

A pair of police constables are presented as scheming gangsters in the service of the state, their hawkish glares almost obscured by their low-brimmed helmets. Their stances suggest rigidity and imbecilic confrontation, not justice.

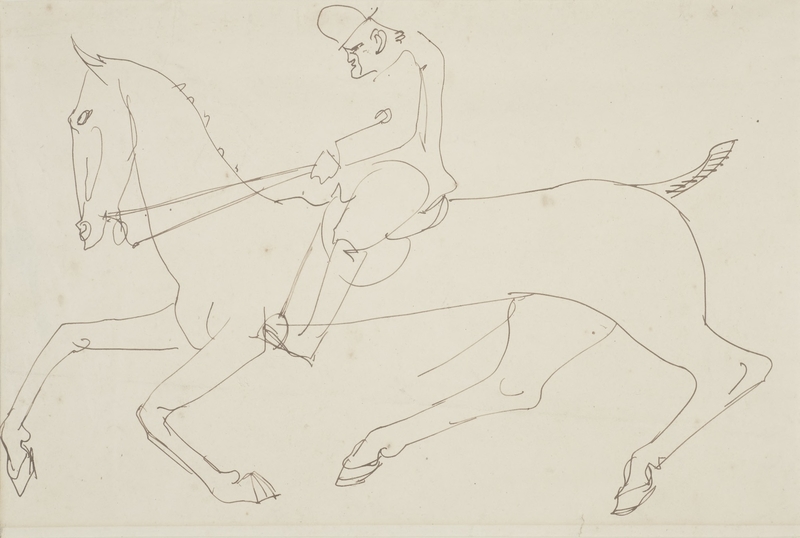

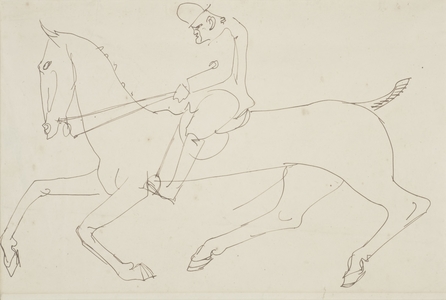

A man on a horse is similarly brought low to comic effect. His limp posture and grim expression suggest he does not share his steed's lust for life which is hinted at by a pricked tail and a single well-placed line between its legs. The rider's bowler hat – increasingly associated with bankers in the City of London in the early twentieth century – implies this may be Gaudier-Brzeska's 'flabby faced plutocrat' or one of his lackeys speeding along the street seen through the eyes of the pedestrian-flâneur.

These are both rapid street sketches in which the artist's pen and ink form part of the maelstrom of modern London, but they do not venerate state power as, for instance, William Nicholson's print series of 'London Types' had done in the 1890s. Through these sketches, we can almost hear the rapid scratch of Gaudier-Brzeska's nib against paper and with it the aggression of class conflict. Their fidgeting lines embody a search for liberty from legal and financial repression.

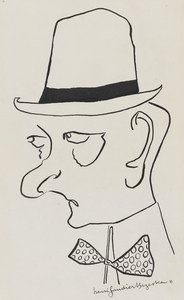

A more classic and less overtly political example of caricature can be found in Gaudier-Brzeska's sketch of Lord Alfred Douglas, the erstwhile lover of Oscar Wilde and glittering youth of the fin de siècle. By 1913, when he was drawn surreptitiously by Gaudier-Brzeska while dining in the Café Royal, Douglas was mellowing into middle age.

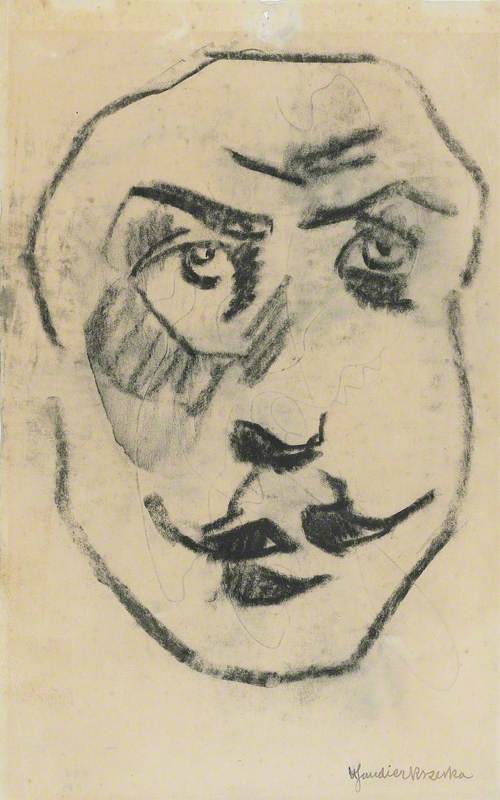

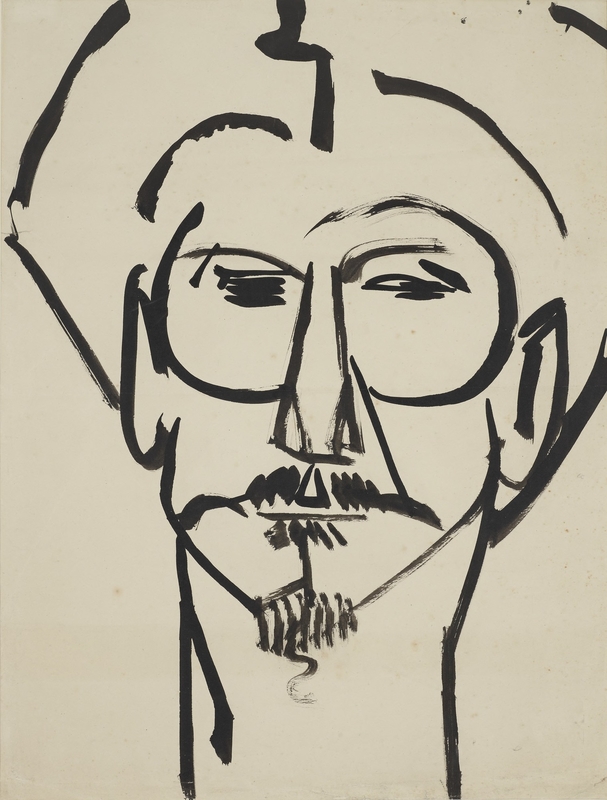

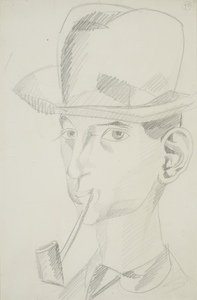

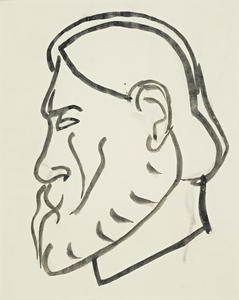

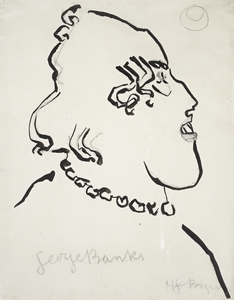

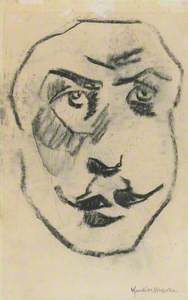

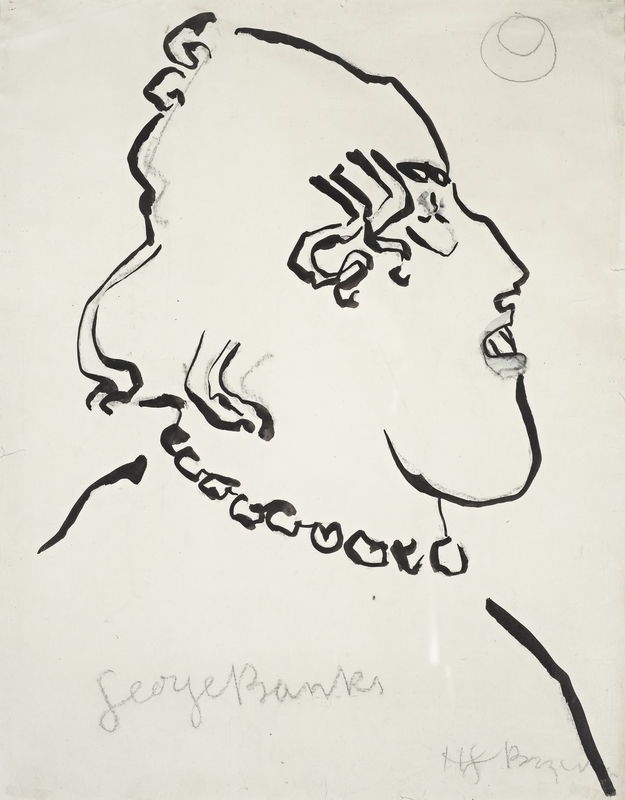

Caricature of Georges Banks (1885–1953)

1912–1913

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska (1891–1915)

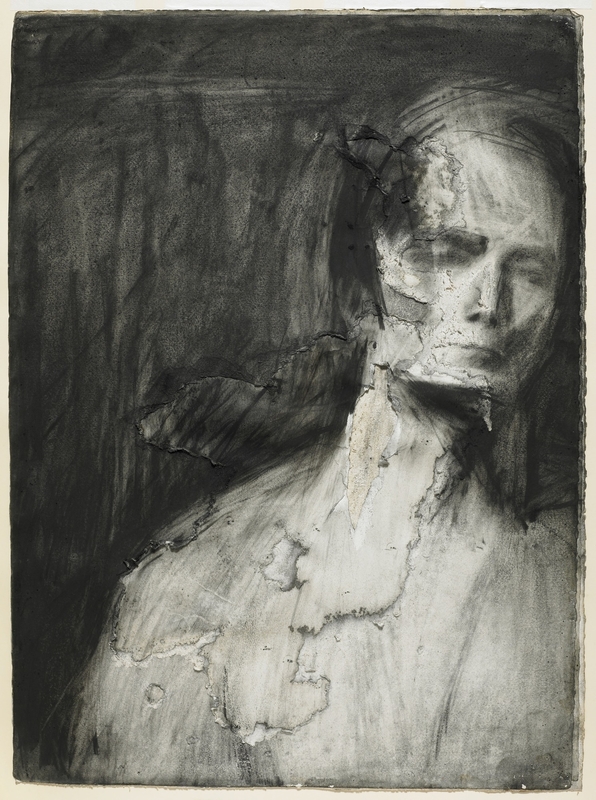

Another example is his depiction of Dot 'Georges' Banks, the Scottish artist and ally to Gaudier-Brzeska in his friendship-cum-feud with the writer and editor of Rhythm, John Middleton Murry. Gaudier-Brzeska's biographer describes Banks as 'a large woman, dressed in masculine clothes, with a round fleshy face, short dark hair parted at the centre, a lopsided grin and slightly divergent eyes.' This uncharitable description is hardly improved upon by Gaudier-Brzeska's drawing in which her hair is a barely coherent scribble and her mouth a grimace fixed to a mountainous chin – a reminder that not even his friends could consider themselves safe from his caustic ink.

In 1913, Gaudier-Brzeska met Ezra Pound and the latter wrote of their 'long, gay, electrified arguments' about anarchism. Their debates were informed by the writing of Dora Marsden, who edited The New Freewoman, later renamed The Egoist, a journal that helped spread the ideas of Henri Bergson and Max Stirner – two philosophical lodestars guiding The Egoist's embrace of anarchist individualism.

By early 1914, Pound was immersed in the work of Ernest Fenollosa, an American specialist in east Asian art who described Chinese written characters as 'a vivid shorthand picture of the operations of nature' so that a sentence takes on 'the quality of a continuous moving picture.' Experts on Chinese writing have since dismissed Pound's and Fenollosa's pictographic interpretation of calligraphic characters. Nonetheless, according to the literary historian David Kadlec, Pound's emphasis on the embodied and dynamic immediacy of calligraphy reflects his eagerness to align it with the 'direct action' politics of anarchism.

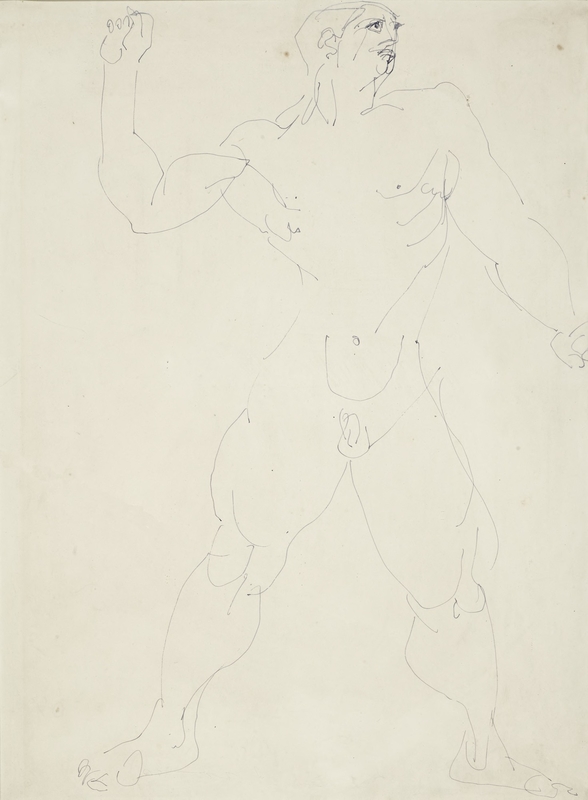

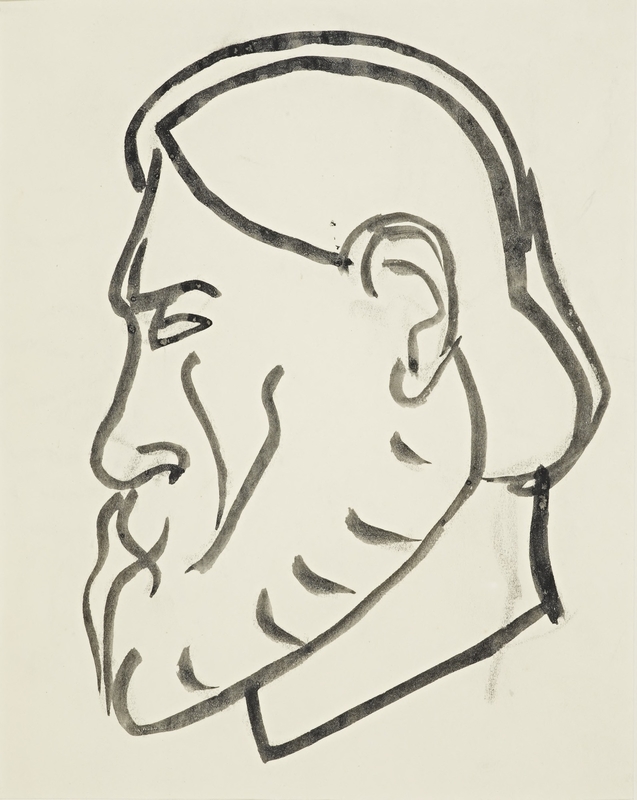

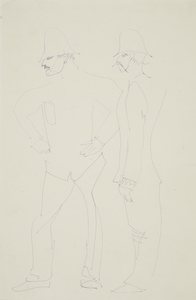

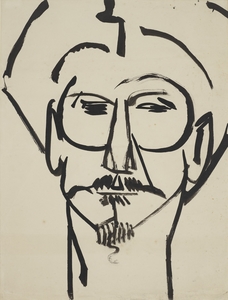

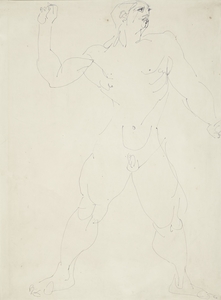

Gaudier-Brzeska enthusiastically embraced this new approach to draughtsmanship informed by Chinese aesthetics and used it to carry forward much of the political intent established through his earlier work in caricature. Even before meeting Pound, he used brush and ink in sweeping, fluid lines to capture impressions of labour figures such as an anonymous man at work in a suitably red hue and portrait in profile that is likely to be Keir Hardie, the trade unionist and founding member of the Independent Labour Party.

On 13th May 1911, Gaudier-Brzeska participated in a major rally in Trafalgar Square in support of the South Wales Miners' Strike where he saw Hardie deliver a stirring address to the massed crowds and made at least two sketches of him. This later brush and ink version is simplified using a bare economy of line to give this talismanic political figure a distinctly archaic, even religious, quality which pre-empts Gaudier-Brzeska's Hieratic Head of Ezra Pound completed in 1914 and invites comparison with the Egyptian hieroglyphic and cursive writing systems which fascinated the artist at the time. Hardie had strong links to the anarchist-syndicalist networks in Paris and Gaudier-Brzeska would have immediately recognised the English militant labour movement as part of the same struggle he had recently left behind in Paris.

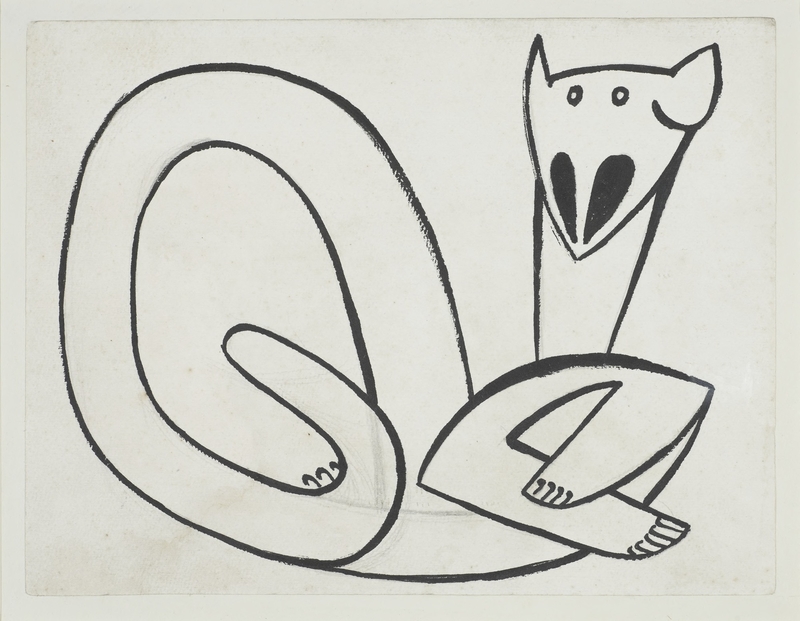

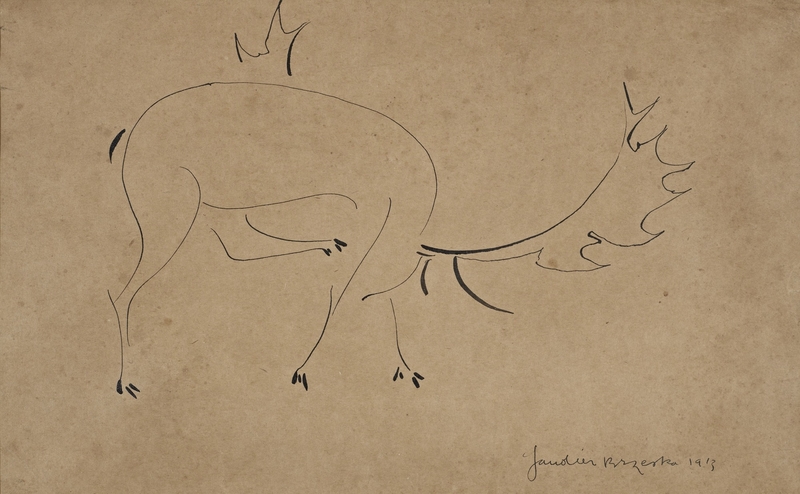

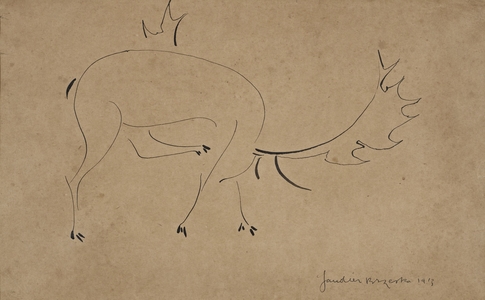

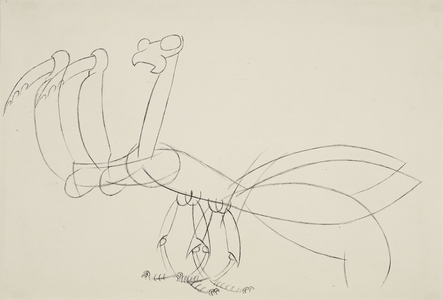

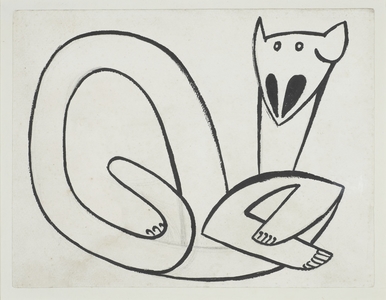

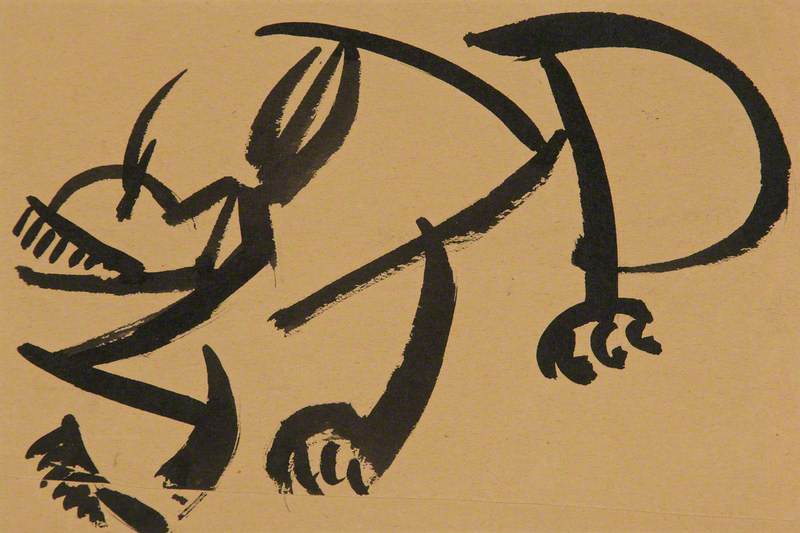

Writing in The Egoist in March 1914, Pound stressed the 'Chinese' quality of Gaudier-Brzeska's sculpture and commented on the similarities between his Boy with a Coney carving and bronze sculptures of animals cast during the Zhou Dynasty (1046-256 BCE). Pound even described the years after their meeting as Gaudier-Brzeska's 'calligraphic' period in which he produced a series of studies of deer. These beautiful drawings are as elegant as they are powerful, their lines like strong, supple branches full of the sap of life, or in Bergson's terms, élan vital. Equally representative of this period is the Cat about to Pounce, a crumpled mass of tooth and claw, with an arched back and swishing tail that threatens to disintegrate into the abstraction of musical notation. The stark simplification of the stag equals that of the cat, but the grace of one gives way to the aggression of the other.

Cat about to Pounce

(recto) c.1913

Henri Gaudier-Brzeska (1891–1915)

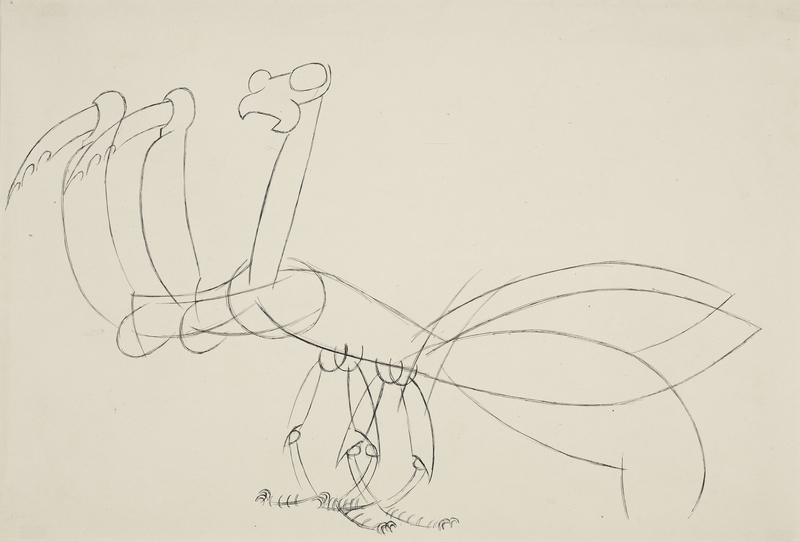

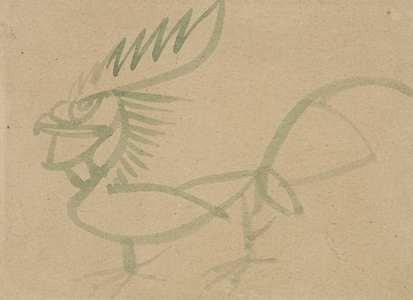

As he was making these drawings, Gaudier-Brzeska stalked the back streets of East London in a long black cape brawling with local gangs and attended anarchist meetings in Soho. His drawing of a cock – a fighting animal, a symbol of the French state, and of victory – reflects how he had used his political experience to work his way into France's subversive tradition of satirical drawing and arrive at a form of self-conscious critique in the spare linear expression of east Asian art.

The cock combines a Chinese calligraphic method with traces of cartoonish exaggeration carried over from the artist's interest in caricature. But does this fusion create a satire of nationalist aggression, or is it evidence of Gaudier-Brzeska's troubling affection for violent machismo which he shared with other avant-gardists, including T. E. Hulme and Wyndham Lewis? It could well be both, and whatever we decide, Gaudier-Brzeska urges us to remember how he could turn a simple portrait, or an energetic sketch of an animal, into a furious critique against the pomposity of capitalist society and a prelude to physical action against it.

Sean Ketteringham, historian and writer

This content was funded by the Bridget Riley Art Foundation

Further reading

Mark Antliff, Sculptors Against the State: Anarchism and the Anglo-European Avant-garde (Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2021).

Rebecca Beasley, Ezra Pound and the Visual Culture of Modernism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007).

H.S. Ede, Savage Messiah: A Biography of the Sculptor Henri Gaudier-Brzeska (Leeds; Cambridge: Henry Moore Institute; Kettle’s Yard, 2011)

Ernest Fenollosa and Ezra Pound, ‘The Chinese written character as a medium for poetry, [II]’, Little Review, 6.6 (1919), 57-64.

David Kadlec, Mosaic Modernism: Anarchism, Pragmatism, Culture (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000).

Paul O’Keeffe, Gaudier-Brzeska: An Absolute Case of Genius (London: Allen Lane, 2004).

Patricia Leighten, ‘Reveil Anarchiste: Salon Painting, Political Satire, Modernist Art’, Modernism/modernity, 2.2 (1995), 26-27.

Ezra Pound, Gaudier-Brzeska: A Memoir (London: John Lane, 1916).

Ezra Pound, ‘Exhibition at the Goupil Gallery’, Egoist, 6.1 (1914), 109.

Evelyn Silber, Gaudier-Brzeska: Life and Art – with a Catalogue Raisonne of the Sculpture (London: Thames and Hudson, 1996).

Lisa Tickner, Modern Life and Modern Subjects: British Art in the Early Twentieth Century (London: Paul Mellon Centre, 2000), ch. 3.