Volcanoes have long been an alluring prospect for artists. They’re dramatic, belching plumes of flame and rivers of lava; they’re surrounded by stories and myth; and, for artists used to Britain’s geological mundanity, they’re exotic.

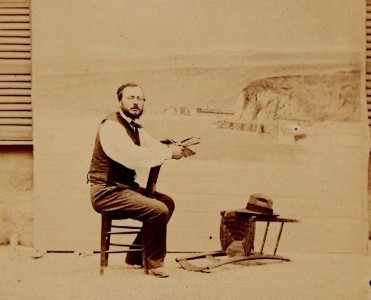

Artists including Joseph Wright, Marianne North, Turner and Warhol, have turned their attention to these mysterious, fire-breathing mountains. They were enough of a pull for intrepid observers to brave the trek up their ashy sides in the 1700s, making sketches and observations before scuttling back down to the safety of the easel to record their experiences on canvas.

A 2017 exhibition at the Bodleian Library pulled together early volcano artefacts – including such gems as a burnt scroll from Herculaneum, and a coin from 1816 preserved in lava – with early journals and artworks of those daring people who explored volcanoes, bringing together art and science in the history of volcanology.

Volcanoes in art and science: a Venn diagram?

Impressive as paintings of volcanoes are, they’ve also had a value that goes beyond the aesthetic and into the scientific. We spoke to Professor David Pyle, a volcanologist and curator of the Bodleian’s exhibition, who thinks that paintings by artists from the eighteenth century form part of a valuable body of evidence.

David explains, ‘The theme of our exhibition is that volcanologists are interested in what’s happened with volcanoes in the past… because if we can understand that it gives us a better way of understanding what might happen in the future. But the timescale of scientific observation is very short, whereas the timescale in which people have written about volcanoes or reported seeing things at volcanoes is rather longer. We’ve only been making formal scientific observations of volcanoes since about the 1850s, or maybe the 1830s. And those observations are few and far between – some volcanoes haven’t tended to be very accessible. Globally, there are probably 600 volcanoes that have erupted in the last 300 years. And for many of those, the first eruption that’s well known would be from a report from a passing traveller, or explorer, or the effect was large enough that enough people wrote it down and it ended up in the news.’

So, before scientific observation began, paintings were one way in which evidence could be collected and, alongside artefacts and written documents, form a body of evidence about the activities of volcanoes. But how accurate were these paintings? The most-painted volcano on Art UK is Vesuvius. Numerous paintings were commissioned by diplomats, like William Hamilton, and wealthy tourists who wanted a memento of their time in Italy. Was much artistic licence taken?

According to David, it probably wasn’t necessary to embellish the reality: ‘Through the 1700s, it was fascinating to see how the depiction of Vesuvius changed... certainly Joseph Wright made some really impressive paintings… My understanding is that those are among the first artistic depictions of volcanoes that were nonetheless trying to represent faithfully the idea of nature and what was actually happening at the volcano, rather than simply being impressive but made up.’

Vesuvius in Eruption, with a View over the Islands in the Bay of Naples

c.1776–80

Joseph Wright of Derby (1734–1797)

The above painting by Wright, from the late 1700s, is an excellent example. We know that Wright toured Italy between 1773 and 1775 – too early to be witness to the major eruption of Vesuvius in 1777. Yet he painted over 30 views of the exploding volcano: something had inspired him.

It’s entirely possible that Wright saw something dramatic enough to make a serious lasting impression – particularly for an artist more accustomed to the gentle hills of Derbyshire.

As he describes, ‘from 1631 to 1944 Vesuvius was essentially erupting all the time. Sometimes it was dramatic, sometimes less so... looking at the Joseph Wright piece, that’s really captured the state of the volcano as it would have been in the 1770s. A big, ancient crater, that forms the background to the cone, which is the active part of the volcano, and at night you wouldn’t have needed a particularly strong eruption to give you this sense of fire coming off the top of the cone, and then the tumbling blocks, red hot blocks, tumbling out of the vent would feed the lava flow around the base of the cone. So those elements are all things which I can certainly imagine being real. It was certainly the case that when there was a full moon, and Vesuvius was erupting, it was a very popular night time pastime to climb up and see the fireworks.'

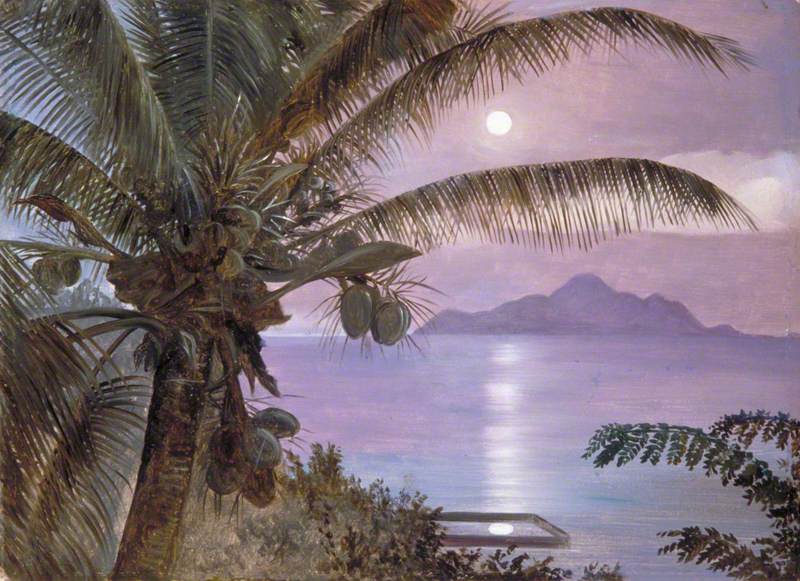

Less accurate may be the paintings made by the ‘Volcano School’ of artists who became intrigued by two Hawaiian peaks, Mauna Loa and Kilauea. This painting of the bubbling inner crater of Mauna Loa is attributed to William Hodges, who accompanied James Cook on his exploration of the Pacific, when Cook became the first European to make formal contact with the Hawaiian islands. However, the first successful expedition to the summit of Mauna Loa was thought to be in 1794, so this painting of a bubbling crater is more likely from the artist’s imagination.

The Inner Crater of Mauna Loa, Hawaii

William Hodges (1744–1797) (attributed to)

Later on, from the mid-nineteenth century, we have representations of Kilauea, which are more likely to be accurate, as we know artists made the gruelling two or three day trek up its slopes. As David says, ‘From about 1826, there were regular expeditions to the summit of Kilauea and so the Charles Furneaux (see below) is clearly a representation of a lava lake in the crater, which is called ‘Halemaumau’ or the ‘house of the spirits’.’

The Crater of Kilauea, Hawaii, USA

1883

Charles Furneaux (1835–1913)

Fantastic theories and where to find them

Another intriguing aspect of the relationship between volcanoes and art is whether they have influenced artists more than they might have realised. A Greek physicist, Christos Zerefos, has conducted research into the colour of the skies in paintings, suggesting that the prevalence of warm hues in the skies of paintings isn’t due to artistic license, but actually indicates the presence of volcanic ash and dust in the atmosphere when the artworks were created. Perhaps the skies in Munch’s The Scream can be connected with the eruption of Krakatoa in 1883? It’s a fascinating hypothesis, and explained further in this piece by the Smithsonian.

One story that has become widely accepted is that of the 1816 ‘summer of rain’, where Mary Shelley and companions were stuck indoors in Geneva. As the rain poured down outside and lightning flashed, they started telling ghost stories to pass the time: from which Frankenstein was created. And the reason it rained relentlessly all summer? The eruption of Mount Tamboro in Indonesia in April 1815, which sent clouds of volcanic ash billowing into the upper atmosphere.

The end of the affair

In the late 1800s, along came photography, and artists were no longer needed to go and paint volcanoes on commission. The first set of photographic images capturing Vesuvius erupting are from around 1872, and by the early 1900s photography was routine. So it is accurate to say that there was a sort of golden age where volcano art formed an important part of research? David thinks so: ‘I think that would be a fair representation, yes… if it happened these days you’d go on social media and Instagram to find photos that people had taken and uploaded, whereas when Vesuvius erupted in the 1770s, you’d go looking for painters to work’.

Molly Tresadern, Art UK Content Creator and Marketer

'Volcanoes' was on display at the Bodleian Library from February to May 2017