The paintings of quiet interiors and portraits of solitary women for which Gwen John is best known have been widely written about since her death in 1939. Her work has been interpreted both in isolation and as part of a disjointed understanding of modern British art.

Historically, she has been compared to her brother Augustus John whose oeuvre was substantially larger than her own, and her affair with the most famous sculptor in Western art at the time, Auguste Rodin, has often clouded her legacy rather than enhanced it. However, the most prominent myth impacting Gwen John's scholarship is that she was a recluse.

There is no doubt that Gwen John was both a complicated artist and a complicated woman – aren't we all – but contemporary literature, including the most recent biography Gwen John: Art and Life in London and Paris by Dr Alicia Foster, refines our understanding of John as an artist who was sociable and connected with the world around her.

One aspect of John's sociability which allows us to understand her position amongst her peers is her role as both a student and a tutor. Between 1895 and 1903, Gwen John was part of a network of artists in London and a student at the Slade School of Fine Art. She was one of several students who studied under Henry Tonks and Frederick Brown at the Slade, but there was also a significant amount of informal tutorage that took place between John and her peers that should not be underestimated.

Encouraged by tutors to visit The National Gallery, the British Museum, and the National Gallery of British Art (now Tate), John and her classmates would work from Old Master paintings and drawings on display in the hope of gleaning techniques from Europe's greatest artists. This was also an opportunity for students to meet outside the classroom and share their own experiences of successful and unsuccessful experimentation.

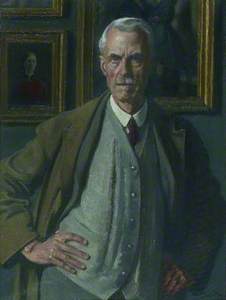

Gwen John was close friends with the artist Ambrose McEvoy, a fellow Slade student who would later go on to become one of the leading society portraitists of the 1920s. It has often been noted that the two artists had a romantic relationship, however, there is little, if any, tangible evidence for this. They did, however, learn from each other as artistic equals.

The art historian and former Tate Director John Rothenstein wrote, in his 1956 book Modern English Painters (although she was, of course, Welsh), that Gwen John was greatly influenced by McEvoy and his interest in Old Master paintings and drawings – a knowledge that he 'laboriously acquired' and 'generously imparted' to John.

'Without his help, she could hardly have painted the Self-Portrait in a red sealing-wax coloured blouse... This portrait – to my thinking, one of the finest portraits of the time, excelling in insight into character and in purity of form and delicacy of tone any portrait of McEvoy's – owes the technical perfection of its glazes to his knowledge.'

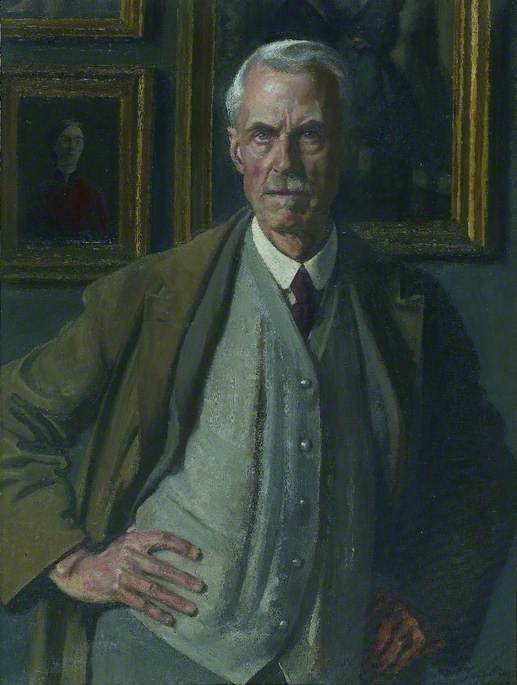

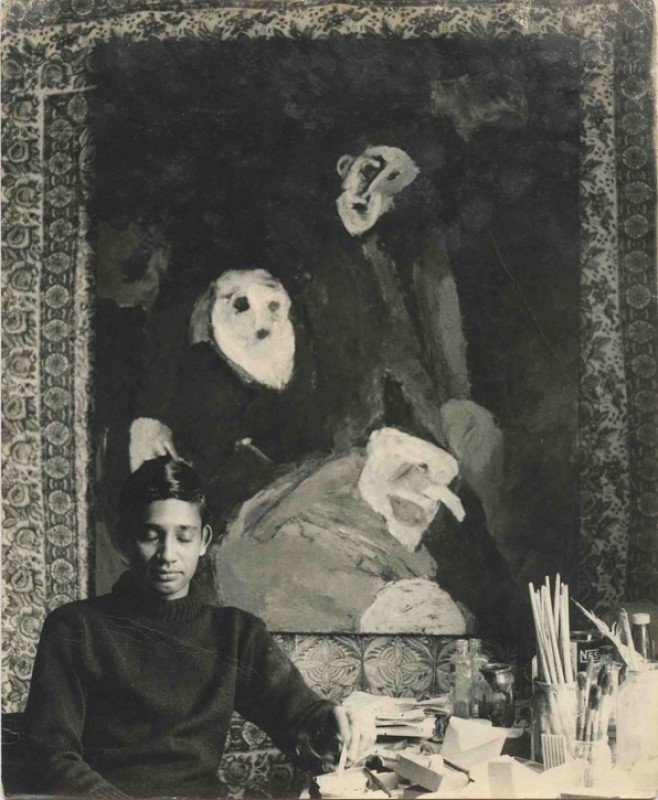

The painting to which this quotation is referring is Gwen John's Self-Portrait (above). It was exhibited in the spring of 1902 at a Slade exhibition for former students. John is thought to have painted the work between January and April whilst she was staying in Liverpool with her brother Augustus. This is an accomplished and experimental portrait for John at this period: it was highly regarded by her peers and was bought immediately by Professor Frederick Brown at the Slade. Brown later included this work in his own self-portrait in 1926.

It is very possible that Gwen John learnt the technique of layering thin, coloured glazes over a monochrome base for her self-portrait from studying alongside McEvoy in The National Gallery. She certainly worked in the gallery and copied Gabriel Metsu's A Woman seated at a Table and a Man tuning a Violin in the 1890s.

A Woman seated at a Table and a Man tuning a Violin

about 1658

Gabriel Metsu (1629–1667)

However, Rothenstein's suggestion that John could not have produced this self-portrait without McEvoy's direction or tutoring is, quite frankly, insulting. In reality, McEvoy and John both influenced each other and there is evidence that McEvoy copied directly from Gwen John's portrait of Mrs Atkinson (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) on several occasions in his sketchbooks.

In 1901, McEvoy painted Gwen John's portrait in his room/studio at 24 Danvers Street in Chelsea. This work is notable as it is closer in style to McEvoy's later portraits rather than his highly finished interiors from this earlier period. This portrait has bold and confident brushstrokes which give the sitter's clothes tactility and even a sense of movement, though John herself is seated and static. The face of Gwen John is not as accomplished as other figures in McEvoy's paintings and the cheek and jawline have been reworked from the original position. Bearing this in mind, it is very likely that Gwen John, as an artist and friend, would have offered advice to McEvoy throughout this process and may have helped influence his later style of portraiture.

By the time McEvoy painted her portrait, Gwen John had completed several months of training at the Académie Carmen with tutor James McNeill Whistler. Whistler's teaching on the use of tone and colour in oil painting, and his insistence that a palette be laid out in a particular way, was something that John brought back with her to London to share with other students.

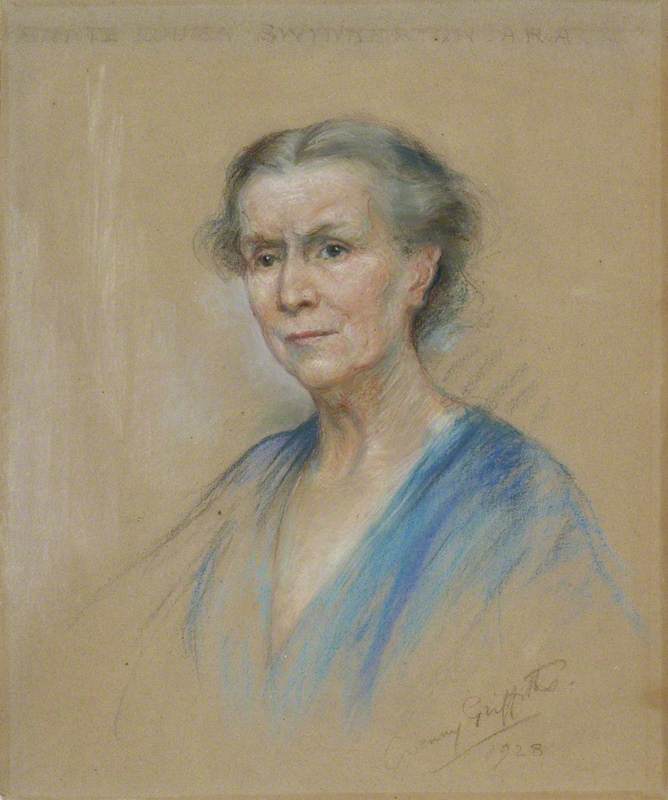

She taught her friend Edna Clarke Hall (née Waugh) who wanted direction in painting with oils. Clarke Hall had been described as an infant prodigy at the Slade and one of the school's most talented students. She had initially studied alongside Gwen John but, having married at the age of just 19 and now entering the next chapter of her life, Edna Clarke Hall looked to her friend to teach her. Art historian Mary Taubman interviewed Edna Clarke Hall in 1974 and asked her about Gwen John's teaching:

'From their painting sessions together she [Edna] remembered above all Gwen John's insistence on a clean and orderly palette, her exacting attention to the rightness of tones – particularly in transitional passages – and her repeated instruction "If it isn't right, take it out!" ... Orderliness and method and an emphasis on "good habit" were what Whistler preached to his students.'

Under Gwen John's tutorage, Edna Clarke Hall painted Still Life of a Basket on a Chair. Dr Alicia Foster suggests that Clarke Hall's composition was likely set up by John as the painting includes carefully chosen props that appear in John's later work in Paris – the straw hat, the wicker work and the chair. Edna Clarke Hall is not known for her oil paintings, working predominantly in watercolour. However, the thoughtful use of tones and the ease with which this still life has been painted almost certainly owes credit to John's teaching.

There is no doubt that students at the Slade during the 1890s influenced each other and benefited from being tutored by Henry Tonks and Frederick Brown. However, Gwen John's transition from being a student at the Slade and studying with Whistler in Paris, to advising and tutoring her peers Ambrose McEvoy and Edna Clarke Hall, is proof of John's early and recognisable talent. It also builds on a more recent narrative of Gwen John scholarship – that she was confident in her own abilities and an artist at the centre of a sociable and contemporary art world.

Lydia Miller, Assistant Curator at Pallant House Gallery

The exhibition 'Gwen John: Art and Life in London and Paris' is showing at Pallant House Gallery until 8th October 2023