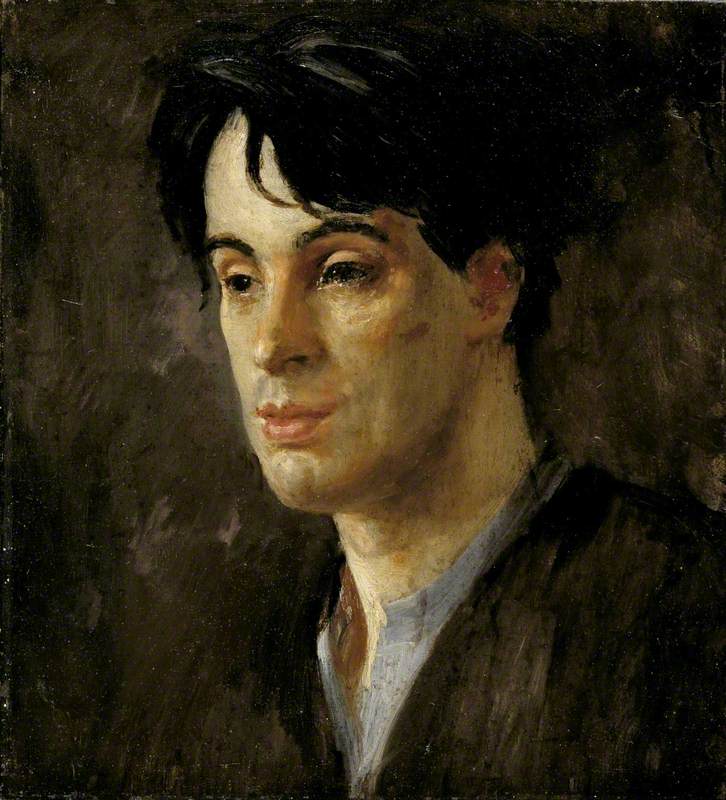

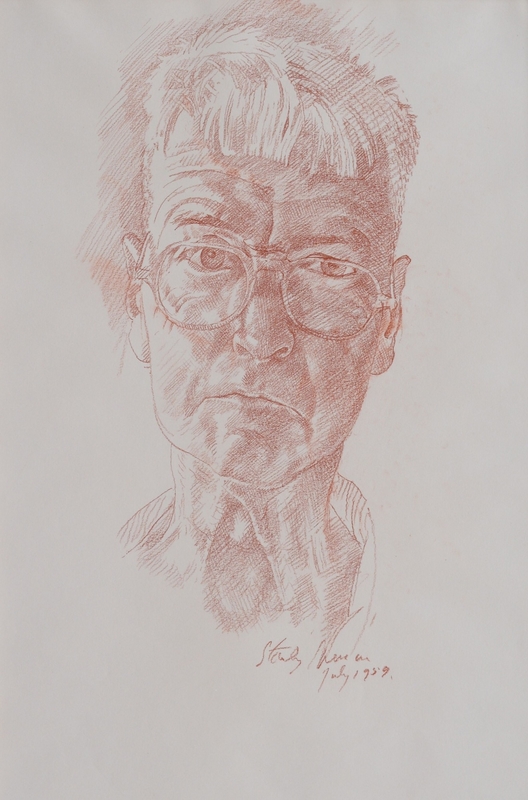

The artist Gluck consistently broke gender norms. They wore masculine clothes, cut their hair short and smoked a pipe and, in 1918, in their early 20s, adopted the genderless name Gluck ('no prefix, suffix or quotes', as they asserted). Although this self-portrait of 1942 is small in scale, as was much of Gluck's work, it has tremendous presence. The artist's expression is simultaneously haughty and confident, yet somehow sad and weary.

Born Hannah Gluckstein into the family that founded the Lyons catering empire, Gluck attended classes at St John's Wood School of Art in London from 1913 to 1916, and then spent time at the artist's colony at Lamorna, Cornwall. It was there that Gluck met painter Laura Knight, whose studio they later bought; the ceramicist Ella Naper, whom they also painted; and Alfred Munnings, who sketched Gluck's portrait.

In 1936, Gluck painted a double profile portrait to commemorate their romantic union with the writer and socialite Nesta Obermer. The work, with its overt lesbianism, would have been considered provocative and subversive at a time when female relationships were censured. The painting was later used on the cover of a 1983 Virago edition of Radclyffe Hall's seminal 1928 novel The Well of Loneliness, about a lesbian relationship.

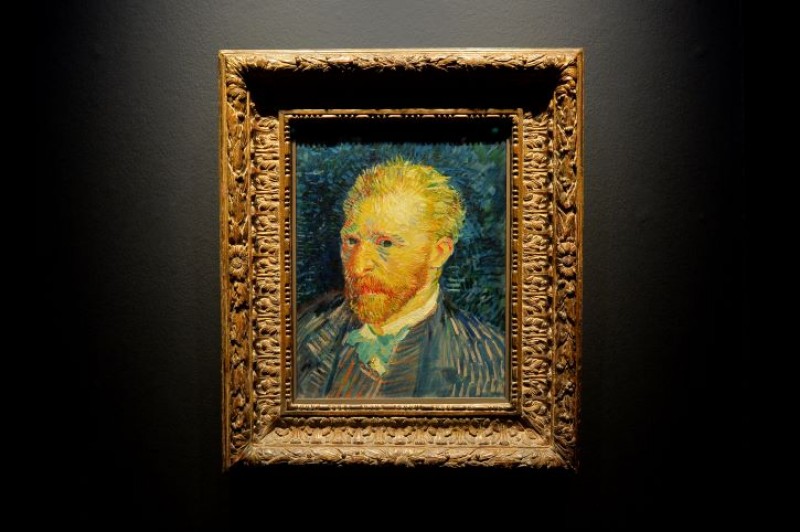

In the 1950s, Gluck successfully campaigned for better-quality paints, persuading the British Standards Institution to create a new standard for oil paints. Several years earlier, in 1932, Gluck designed and patented the popular art deco-style Gluck frame – a three-tiered design that was painted or papered to match the wall on which it was hung, giving the illusion that the painting was part of the architecture of the room. It was exhibited at British Art in Industry exhibitions and became an integral part of modernist and art deco interiors of the 1930s. This image, however, is in a small, white Whistler frame that Gluck used in the 1940s for smaller portraits.

The work was given to the National Portrait Gallery in London by the artist in 1973, five years before their death.

Rosie Broadley, Head of Collections Display (Victorian–Contemporary), National Portrait Gallery