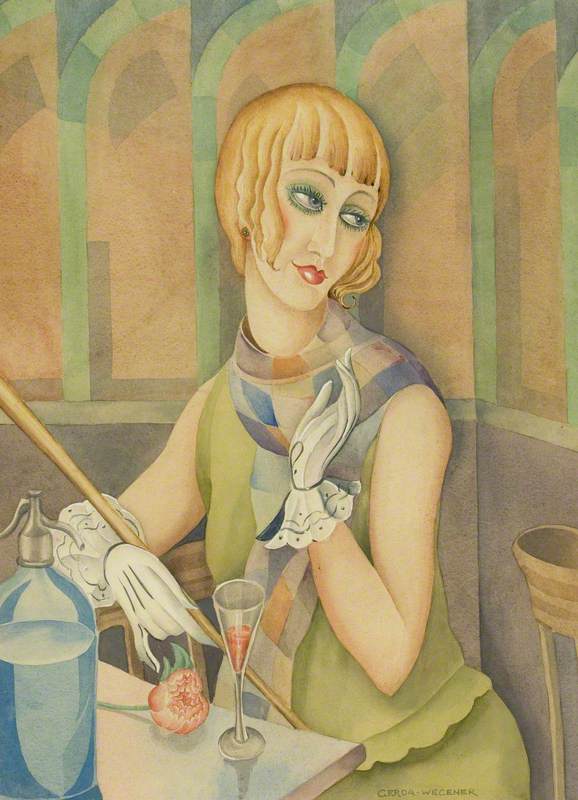

'Today, we're going to talk specifically about the opera glove'. This line is not an entry from an outmoded book on etiquette, but from a recent Vogue article.

We may associate the evening glove with bygone eras, yet the accessory – redolent of Hollywood glamour – has made a comeback in the twenty-first century. Gloves are no longer the distant relative of the fashion accessory family, or a desperate, last-minute Christmas present.

The Woman with a Glove

1870, oil on canvas by William Bouguereau (1825–1905)

In former centuries, gloves were not reserved as winter accessories, but critical to the daily dress of those who could afford them. A beautifully embellished glove could signify status or wealth or draw attention to elegant hands and fingers. Importantly it could provide a vital barrier between the sexes, preventing the frisson of touch and preserving modesty.

Looking closely at gloves and their wearers in paintings can reveal clues about a sitter's position in society, their tastes and the history of the glovemaking industry, which once enjoyed a high reputation in England, centred around towns such as York, Shrewsbury and Worcester.

Portrait of a Lady in a Fur-Trimmed Dress Holding a Pair of White Gloves

c.1660–1670

Jan Albertsz. Rotius (1624–1666) (attributed to)

References to gloves date back to the dawn of humankind. Cave paintings suggest that mittens were worn in the Ice Age, and even the ancient Greek writer Homer mentioned gardening gloves. The oldest surviving gloves are thought to be those found in the tomb of Tutankhamun. Gloves have performed both protective and ceremonial roles for millennia but it is only really in the late sixteenth century that we see gloves take their place on the fashion stage.

Queen Elizabeth I ('The Ditchley portrait')

c.1592

Marcus Gheeraerts the younger (1561/1562–1635/1636)

In the 'Ditchley' portrait, Elizabeth I stands on a globe symbolising her power and influence. Her impossibly lavish dress is festooned with jewels and she wears ropes of precious pearls around her neck. Why then would she carry a modest pair of gloves in her hand? One explanation is that they draw attention to her lily-white hands. Elizabeth was 59 at the time and very proud of her hands. At one ceremony, she is said to have 'pulled off and put on her gloves over one hundred times so that all might enjoy her graceful movements.'

Elizabeth also favoured jewelled and embroidered gauntlets, sparking off a trend amongst courtiers and engendering an expansion of the glove industry. Tassels, gold and silver thread and appliqued design all featured on the fashionable glove.

Seventeenth-century men's gloves

Gloves such as this pair, made of the softest kid leather, lined with pink silk and embroidered with silver thread, were a marker of social standing and wealth. The elongated fingers balanced out the gauntlet cuff, turning the stubbiest of hands into elegant appendages. It was made clear that these were gloves as fashion and not for protection.

Gloves were also given as courtship gifts, as Shakespeare alludes to in A Winter's Tale, when the shepherdess Mopsa remarks to her sweetheart: 'Come, you promised me a tawdry-lace and/a pair of sweet gloves.'

We do not know the age of the young girl in Mytens' portrait but the roses she touches and the kid gloves she holds, lined in cream silk, might just similarly signal an approach from a potential suitor.

Portraits of this period frequently show plain gloves of this type, although the rest of a costume may be very elaborate. Gloves were bought in quantity: the Wardrobe Account for 1608 for Prince Henry of Wales lists 31 pairs of gloves, most of which were plain.

Plain gloves were traditionally given as wedding favours, with the quality varying according to the social standing of the guest. They might be perfumed with scents such as rose, lavender, amber or musk as the businesses of glovemaking and perfumery were often interrelated. Those on a tighter budget could choose to perfume the gloves themselves.

Fashion in the time of Charles I turned away from the heavy embellishments of the Jacobean period and ushered in an era of understated style, with a focus on high-quality fabrics and accessories. In Mytens' portrait, Charles can be seen wearing simple fur-lined gloves of the softest leather from Cordoba, Spain – the very best of leathers – which coordinate with the buttery soft boots which mould his calves and fall in relaxed folds. Squirrel or marten were commonly used for linings but as such a small amount was required, offcuts of more luxurious furs might be chosen.

As sleeve lengths followed fashion, getting shorter or longer according to the prevailing trend, so gloves were adapted in length to ensure the entire arm was covered. Miss Dixie's wide waterfall lace sleeves require an elbow-length glove to ensure that she avoids any risk of her skin become tanned in the sun. Pale unblemished skin was highly prized as an indicator of membership of the leisured classes. Light-coloured gloves might also be painted with pastoral scenes or flowers, or with the image of a bracelet or medallion.

As dress sleeves grew shorter in the late eighteenth century, gloves grew longer and featured ties to secure them above the elbow, sometimes with a decorative touch such as a diamante buckle. By this time the industry in Britain had expanded and was making gloves in a variety of materials from kid and black lamb to wool, linen and cotton twill. However, fashionable consumers still preferred gloves made in France or Italy, leading William Pitt to impose a stamp duty on gloves in 1785, in anticipation of sales of over 30 million pairs per year. Many people bought 20 or 30 at a time.

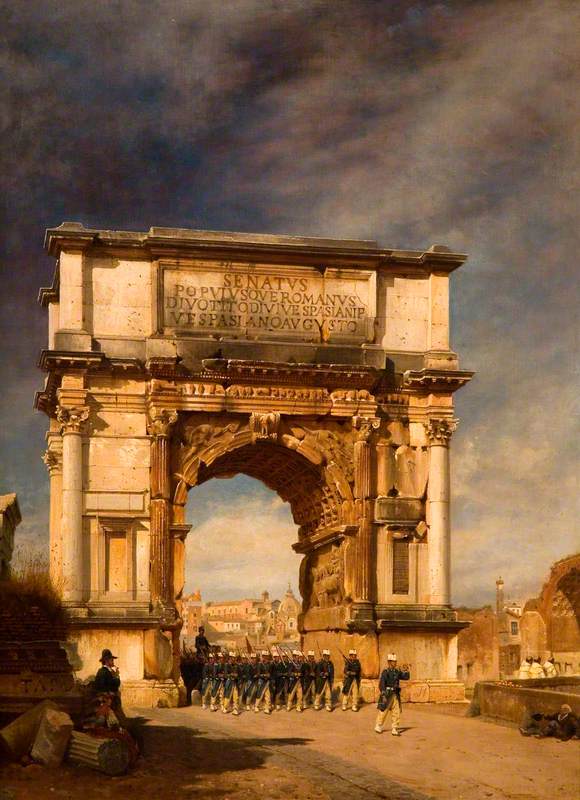

The studio of Pompeo Batoni was frequently booked up by young men of the British aristocracy and landed gentry who beat a path to his door in Rome when on the Grand Tour of Europe. A celebrated portrait painter, Batoni excelled in depicting fabric and texture.

Here John Smyth, later Member of Parliament for Pontefract and Lord of the Admiralty, is portrayed in the classic Grand Tour pose, leaning on a pillar. Batoni echoes Renaissance paintings in showing Smyth wearing one glove and holding the other. This convention has given rise to a number of theories. It makes clear that the gloves are not for work; it allows for the display of precious jewellery (in this case a ring) and it allows for the proffering of a gloveless hand, considered a mark of respect. Any one of these theories might apply here.

Eugène Delacroix's portrait of fellow artist Louis-Auguste Schwiter was his first full-length portrait and shows his friend dressed in the typical dandyish style of the early nineteenth century, with a close-fitting well-tailored suit and smooth leather gloves. The archetypal dandy Alfred d'Orsay advised gentlemen to have six pairs of gloves for the day – two for hunting, one for driving, one for walking and one each for dinner and a ball. Single gloves were exchanged between lovers and it is claimed that after the death of George IV his executors found over 1,000 lone gloves among his possessions.

As dresses became softer and more fluid in the early nineteenth century, gloves too followed suit. The preference was for kid and doeskin in natural colours of buff, tan, yellow and white and a new fashion called from Ireland called Limerick gloves. These were also known as 'chickenskin' gloves but were actually made from the skin of unborn calves. The skins were thin, strong and free of blemishes, enabling the gloves to be packed and sold in a walnut shell.

Hope Deferred, and Hopes and Fears that Kindle Hope

before 1877

Charles West Cope (1811–1890)

The rules of etiquette that governed Victorian life stated that women should always wear gloves at church or to the theatre, but never at dinner, unless their hands were unfit to be seen. A glove might be removed at a ball but the advice was to keep it on if the hands were at all clammy. Gloves and half-mittens now came in coloured silks, lace and embroidered cotton and suited Victorian propriety perfectly in preventing the accidental brush of skin on skin.

Echoing this repressive era, the discarded gloves in Cope's painting offer a powerful symbol either of virtue that has been compromised or romantic hopes that have been crushed. The young woman's hands touch each other – she can only imagine what she has been denied.

In the twentieth century, our attitude towards gloves changed fundamentally. Although, like hats, they were considered an important accessory for respectable women until the 1950s, and enjoyed popularity as both a chaste and seductive element of eveningwear, they increasingly became consigned to special occasions.

Blue Gloves, Orange Chair (Menig Glas, Cadair Oren)

2016

Seren Morgan Jones (b.1985)

During the pandemic we have probably worn more latex surgical gloves than any other type, but perhaps this has prompted designers to look again to how we dress our hands. If Vogue is able to reconjure the elegance and mystique of the glove as a fashion item, then Christmas shopping might start to become fun again.

Lucy Ellis, freelance writer and editor

Further reading

Mike Redwood, Gloves and Glove-making, Bloomsbury, 2016

Valerie Cumming, Gloves, Bloomsbury, 1982