Manchester's 'Art Treasures Exhibition' of 1857 was designed to silence the city's critics that it was all about mills and brass and knew nothing of aesthetics and culture. It was a daring idea. Queen Victoria and Prince Albert were patrons of the exhibition, and the general committee took advice from the German art historian Gustav Waagen. Exhibits of fine art were solicited from public institutions and private collections owned by prominent members of the British aristocracy. Very few refused, although the 7th Duke of Devonshire famously responded 'What in the world do you want with art in Manchester? Why can't you stick to your cotton spinning?'

The 2nd Lord de Tabley (1811–1887), as Colonel Commandant of the Earl of Chester's Yeomanry Cavalry

Francis Grant (1803–1878)

The request to George Fleming Leicester Warren, 2nd Lord de Tabley was received warmly. He agreed to lend some of the choicest possessions that decorated his Palladian mansion Tabley House in Cheshire outside Knutsford. The most important of his loans was the portrait of Lady Leicester as 'Hope'. This was a monumental allegorical portrait by Sir Thomas Lawrence of his mother, Georgiana Maria, Lady de Tabley (1794–1859), commissioned in the early years of her marriage to his father Sir John Leicester, later the 1st Baron de Tabley (1762–1827).

Georgiana Maria Leicester (1793–1859), Lady de Tabley, as 'Hope'

Thomas Lawrence (1769–1830)

In 1857 the painting in the picture gallery at Tabley above a fireplace and against vibrant red flock wallpaper flanked by two enormous wall sconces. Lawrence had portrayed Georgiana in the character of Hope, dressed in a russet-coloured gown with bare feet stepping through clouds holding an olive branch in her right hand. Two fat cherubs appear to be tumbling around the clouds at her feet while a third shy little cherub kneels on a cloud to hold Georgiana's hand. Family legend said that Georgiana's young sons had been immortalised as two of the cherubs.

At the Old Trafford grounds of the 'Art Treasures Exhibition' Georgiana's portrait was hung in a collection dedicated to 'Paintings by Modern Masters'. Her companions included paintings by Raeburn, J. M. W. Turner, Landseer, Constable and two other large portraits by Sir Thomas Lawrence, those of John Philip Kemble as Coriolanus (now in the Victoria and Albert Museum) and that of the late eighteenth-century actress Elizabeth Farren, Countess of Derby (now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York). Georgiana was in good company.

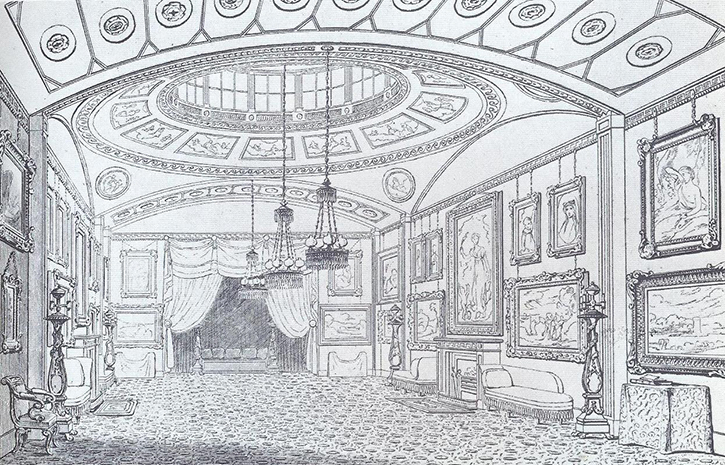

Illustration of Sir John Leicester's London gallery

Georgiana's portrait by Lawrence can be seen on the right-hand side above the fireplace

Prince Albert opened the exhibition on 5th May 1857 and Queen Victoria visited on 29th June. The 'Art Treasures' attracted more than one million visitors, from mill workers to people like William Gladstone, Benjamin Disraeli and Florence Nightingale. The novelist Elizabeth Gaskell hosted numerous visitors to the exhibition at her home in Manchester. In July 1857 the artist William Bewick viewed what had been assembled in Manchester and thought that the exhibition was 'a most wonderful one, and the general effect is almost overpowering.' When he saw Lawrence's Lady Leicester as 'Hope' it stirred up memories of him first seeing the painting as recounted in the 1871 Life and Letters of William Bewick (Artist).

In May 1819, Bewick visited Sir John Leicester's gallery of British art at 22 Hill Street, Mayfair. There was a picture gallery and several smaller exquisite rooms for the display of the many paintings. Bewick had been part of a group assembled by the painter Benjamin Haydon and it included the writer Leigh Hunt, poet John Keats, Edwin Landseer and his younger brother. Bewick recounted:

'Sir John gave orders that when he and his party came he should be informed. He and Lady Leicester and their friends came in to see those remarkable men, and we all were introduced (a very unusual thing on such occasions). Lady Leicester was beautiful, and there was a full-length portrait of her by Sir Thomas Lawrence, equally beautiful.'

The painting was always popular with Sir John's visitors. In the same year as Bewick's visit, The New Monthly Magazine wrote fulsomely of Lawrence's representation:

'The beauty of Lady Leicester is not alone a tincture of complexion, the lustre of a sparkling eye or the freshness of a vermeil lip. It is not merely an angelic exterior inhabited by an uncourteous and earthly spirit. The beauty of her countenance is the unclouded light of the soul, the gentle virtues shining from within and diffusing a charm over all her looks and actions.'

Georgiana Maria (1794–1859), Lady de Tabley

(study)

William Owen (1769–1825)

The Monthly Magazine in 1827 praised Georgiana's 'beauty, kindness and intelligence' and noted that she 'diffused a charm over all who came within the sphere of her influence'. Bewick was clearly smitten as he forgot anything that Sir John might have said in their encounter. But he remembered Georgiana seemed to be fascinated by the party of dark young men (the Landseer boys were actually blond but clearly she had not noticed them) and she asked their guide, 'Mr Haydon, do all your pupils have black hair?'

The Lawrence portrait had been commissioned by Sir John Leicester in 1811, just a year after his marriage to Georgiana Maria Cottin, the daughter of Lavinia and Lieutenant Colonel Josiah Cottin. Georgiana's mother was a daughter of the architect Sir William Chambers and her parents knew the Prince Regent, later George IV, and his mistress Maria Fitzherbert who were Georgiana's godparents.

Prince Regent (1762–1830), Later George IV

Thomas Lawrence (1769–1830) (and studio)

The Cottins were bankrupted in 1797 but managed to secure, through their connections, a grace-and-favour residence in Hampton Court Palace. The Cottins suggested to the Prince that it would be useful if Georgiana could secure a wealthy husband and he thought a union of Georgiana's youth and beauty with his friend Sir John's money seemed sensible. When he brought Sir John to visit, they came across the Cottin girls running around Fountain Court. Georgiana tried to hide behind her sister Anna as she heard the Prince announce, 'Those are old Cottin's girls. No, stand aside short girl, it's the tall girl one wants to look at.' After Georgiana had been stared at, they were allowed to escape. We know all this because Georgiana's granddaughter Eleanor Leighton-Warren wrote it down in her Family Notes.

The Honourable Eleanor Leicester Leighton-Warren (1841–1914)

George R. Chapman (b.1834)

When the Cottins returned home Mrs Cottin announced, 'Georgiana is to be Lady Leicester'. Anna protested, 'What? Is her husband to be that red-faced little old man with the flaxen wig I saw with HRH?' Their mother became angry but, as Anna remembered, 'Georgiana said nothing one way or the other – it seems she thought everything all right that was settled for her.'

Before her marriage, Georgiana was transformed as completely as Eliza Doolittle was by Professor Henry Higgins. She had to take pianoforte lessons, begin French conversation classes and would learn to play the harp. Never had a poor family's solvency depended so much on a daughter's extracurricular activities. Mrs Cottin ordered (at Sir John's behest) a magnificent trousseau; the bill extended over several pages of quality paper and cost thousands of pounds.

When they married, Georgiana was 16 and Sir John was 48. When Sir John's cousin Thomas Lister Parker wrote to the Cottins, he underlined the financial and transactional nature of the marriage. He praised 'Sir John's good fortune in meeting with so great an acquisition as Georgiana'.

Georgiana dressing

pen & ink sketch, thought to be by Georgiana's husband, Sir John Leicester

After her marriage, she was attended by two maids. Sir John apparently kept 'a Turkish woman to amuse her'. Georgiana filled her days with making fine Nottingham lace, paper pricking, singing and she was particularly known for her recitations: Sir John favoured gruesome gothic tales, such as 'Alonzo the Brave and the Fair Imogine' by M. G. 'Monk' Lewis.

Georgiana was as docile as a kitten when she entered Sir John's world and attempted to please both him and her mother. Georgiana herself was 'darling Georgiannie' to her besotted husband and 'angelick Georgiana' to her mother whose letters combined extravagant expressions of maternal love and endless demands for money. When her husband complained about his in-laws and threatened to stop their payments, Mrs Cottin was furious:

'My God! after 17 years of the most unremitting attention to you on our parts as also of the very greatest affection, are we in return because we are poor & distressed to be upbraided for what Sir John Leicester has done for us, remember Georgiana how much we have done for you!'

While Georgiana lived at Tabley 'in such luxury … so well cared for and happy' she was always haunted by her mother's begging letters.

Georgiana performed her duty as expected and gave Sir John two sons: George, later 2nd Lord de Tabley, born in 1811 and William Henry Leicester, born in 1813. The Prince Regent was godfather to Georgiana but also to little George. After that, Sir John's interest in his wife waned although he may not have been very faithful, even in the early years of their marriage. He had a particular trick with one of his paintings: Hoppner's Sleeping Nymph and Cupid (now at Petworth House). It was hidden behind a curtain and before revealing the nude to his assembled guests Sir John would announce, 'Now then, blush up ladies' and, with a flourish, drew back the curtain. He delighted in their exclamations of surprise and embarrassment.

Georgiana resigned herself to life with her ageing and increasingly unwell husband. John Simpson captured Georgiana around this time in his portrait of her, calm and smiling and wearing very good jewellery. She had developed enough confidence within her marriage to tease Sir John when he made a fuss about a female figure in one painting with bare feet, of which he did not approve. While his art collection grew, his financial resources were increasingly overstretched and his fortune was running out. He attempted to sell his collection of British art to the nation but the Prime Minister Lord Liverpool refused the offer. After her husband's death, his famous collection was broken up and sold to satisfy his many creditors. The Lawrence portrait was not included in the sale and was taken to Tabley House.

Just before his death, Sir John Leicester was created the 1st Baron de Tabley by his old friend George IV and consequently Georgiana became Lady de Tabley.

Georgiana and her second husband Frederick Leicester

1847, daguerreotypes by an unknown photographer

Georgiana was not destined to remain a widow for long as her attention was captured by the Rev. Frederick Leicester, her late husband's nephew. He was the kind of dark, handsome young man who had captured her attention when Bewick and company had visited Hill Street. Her sister Anna had noticed Georgiana picking spangles off an old ballgown with Frederick's assistance. Such a marriage was prohibited by the Church of England; it is not entirely clear where and when they married. Anna wondered whether the ceremony was engineered by Frederick and a friend pretending to be a clergyman. A genuine bishop, the Bishop of Litchfield defrocked Frederick and thus ensured his dependence on Georgiana's money. As a couple they lived quietly and in a small way in the south of England. It was a very different life to the one Georgiana had with her first husband.

Inscribed over the entrance to the 'Art Treasures Exhibition' was the first line of Endymion by John Keats: 'A thing of beauty is a joy for ever'. Georgiana's portrait was as vibrant as it had been when it was one of the stars of Sir John Leicester's London gallery. It is not certain that she visited the exhibition and saw her younger self celebrated and immortalised by Lawrence. But she did return to Tabley as a much-loved grandmother in the 1850s, and her grandchildren would celebrate her arrival by showering her with confetti. Georgiana, dowager Lady de Tabley died aged 65 on 5th November 1859.

Georgiana's portrait by Thomas Lawrence still in its place in the Picture Gallery at Tabley House

When the successful 'Art Treasures Exhibition' finally closed, Georgiana's portrait was taken down and returned to Tabley House. It took its place once again on the north wall of the picture gallery. It is still there today and as popular with visitors as it was when displayed in Victorian Manchester.

Sarah Webb, Trustee and Volunteer at The Tabley House Collection Trust