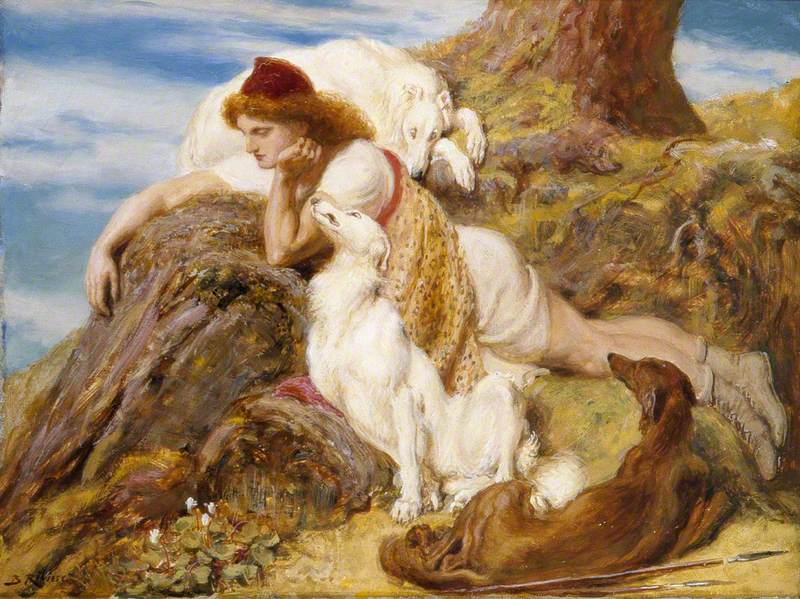

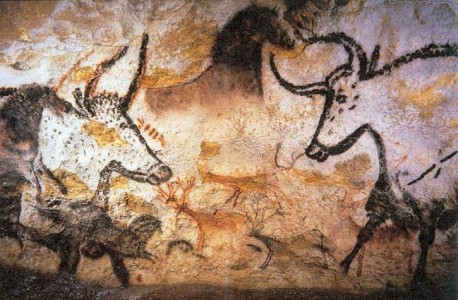

The majority of the Hunterian Museum’s 243 oil paintings are portraits of famous surgeons and Fellows of the Royal College of Surgeons, where the museum is based. But it also holds several intriguing paintings of animals, which give us another insight into the foundation and history of the museum. One such painting is this work by George Stubbs of a drill and albino baboon, dated around 1770–1775. It was commissioned by the founder of the museum, surgeon and anatomist John Hunter (1728–1793), and displayed at its former premises – part of Hunter’s house – on Leicester Square in London.

Drill and Albino Baboon

before 1789

George Stubbs (1724–1806)

The two animals shown in this painting were in the collections of dealers in London. The drill (left) was in the collection of William Gough, who owned an animal shop on Holborn Hill. The albino hamadryas baboon (right) was in the collection of George Bayly, a ‘bird and beast’ dealer in Piccadilly, and records show that it was called the Child of the Sun, ‘probably by a showman’. Although hamadryas baboons were revered by the ancient Egyptians, who believed that some of the baboons’ behaviour showed them worshipping the sun, we will probably never know if the ‘showman’ had this in mind when naming his baboon, or if he simply wanted a sensationalist name to draw the crowds to his rare white animal.

Hunter, like many others at the time, was intensely interested in both exotic new animals and how they should be classified or ordered. He was also interested in albinism, believing that animals became lighter through breeding, in contrast to popular ideas at the time, which held that humans’ skin was originally albinic. This painting captures all these interests, and even the title, which was originally ‘Baboon and Albino Macaque’, reflects the confusion over the taxonomy of apes and monkeys that existed well into the nineteenth century. The drill’s staff, too, can be read as representative of people’s struggle to establish other primates’ relation to man: holding a staff indicated the drill’s proximity to man, but also its less-than-human status, needing help to stay erect in a stance unnatural for it (i). This painting fits into a long tradition of depicting monkeys and apes supported by staffs.

Stubbs’s painting has links to other items across the College’s collections. Hunter, a master dissector and preparator, took several preparations from the animals shown in it, although today only two survive: the drill’s tongue, fauces and larynx (RCSHC/1520), and the baboon’s lymph glands (RCSHC/P 358). The baboon is believed to have died of tuberculosis, although this disease is rare in primates. Such specimens provide valuable evidence for the study of disease and comparative anatomy, although as with the title of the painting, the specimens were originally attributed to the wrong species.

Stubbs studied anatomy too, including practising dissection, and he made studies of both human and animal anatomy throughout his life. His earliest surviving work is not one of the animal paintings for which he is famed, but the illustrations he drew and engraved for John Burton’s An Essay Towards a Complete New System of Midwifery (1751) whilst studying anatomy at York County Hospital. Stubbs made most of the drawings from observing dissections, but some were made from his own dissection of a woman who had died in childbirth. The rather secretive circumstances in which this dissection took place – the corpse smuggled into a garret – could have been responsible for the ‘vile renown’ for which Stubbs was remembered in York for decades afterwards (ii). A dozen or so copies of this work survive in the UK, and one of these is held in the College’s library.

Identifying links such as these between items and across collections has been a cornerstone of the College’s recent Collections Review Project. This project has been assessing the condition, management, usage and significance of the College’s entire library, museum and archives holdings. Recognising these connections allows us to view our collections in context and therefore gain a much richer understanding of them. Stubbs’s painting, like so many items, doesn’t exist in isolation, and is not just a wonderful depiction of two animals by a master of the genre, but a reminder that the long history of anatomy, surgery and disease has a far wider reach than just the operating theatre or practitioner’s office.

Dorothy Fouracre, Collections Librarian, Royal College of Surgeons

(i) W. D. Ian Rolfe and Caroline Grigson, ‘Stubbs’s “Drill and Albino Hamadryas Baboon” in Conjectural Historical Context’, Archives of Natural History, 33.1, 2006, p.21

(ii) Judy Egerton, George Stubbs, Painter: Catalogue Raisonné, Yale University Press, 2007, p.17

Further reading

William Le Fanu, A Catalogue of the Portraits and Other Paintings, Drawings and Sculpture in the Royal College of Surgeons of England, Livingstone, 1960