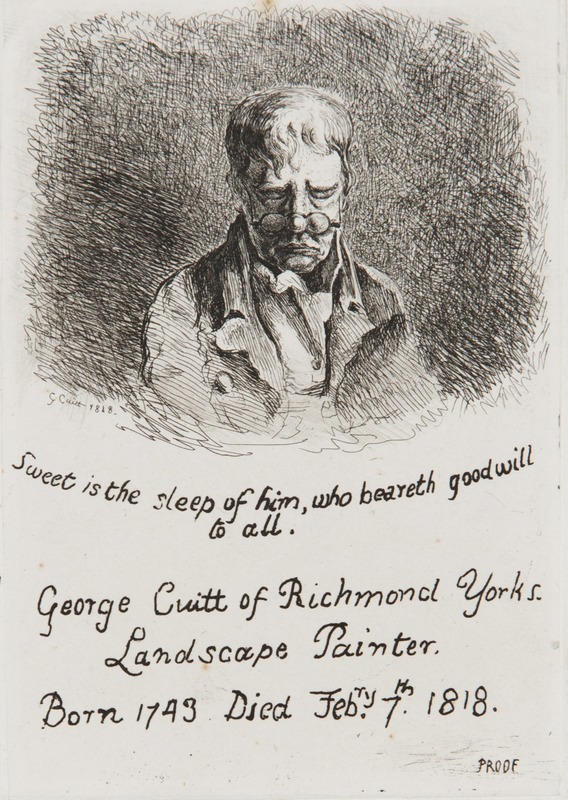

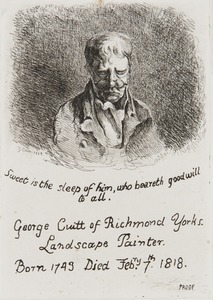

The Grosvenor Museum in Chester has, unsurprisingly, many artworks in its collection depicting this historic city, but amongst the most compelling and evocative are those by a relatively unknown Regency artist, George Cuitt (1779–1854).

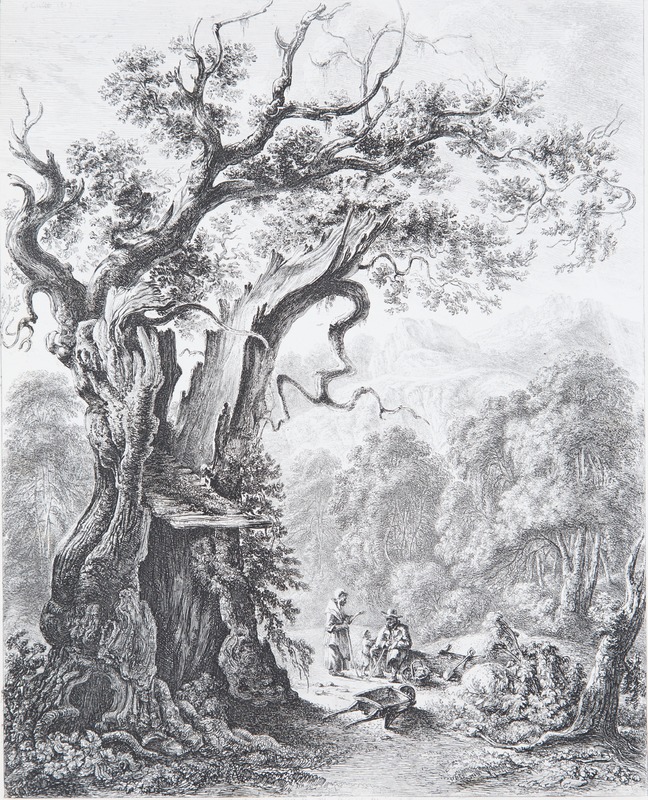

Born and raised in Richmond, North Yorkshire, Cuitt moved to Chester in 1804 to work as a drawing master. He made art in various media but his talents are best expressed through etching. Trained as a landscape artist by his father, George Cuit the elder (1743–1818), he was fascinated by the rundown, the neglected and the obscure.

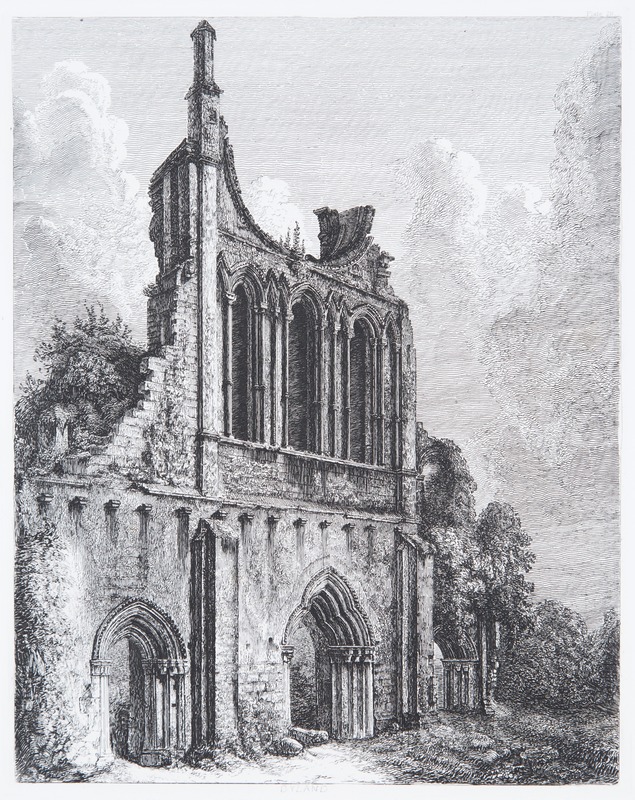

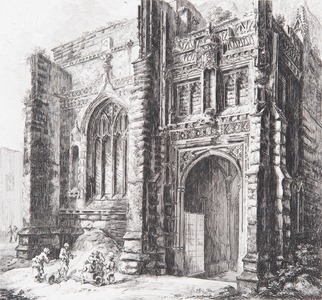

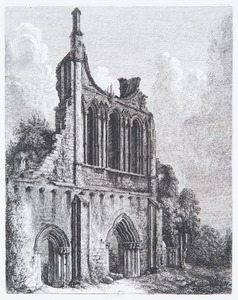

In 1810 Cuitt published a set of etchings called Saxon and Gothic Buildings Now Remaining in Chester, including views of Chester Cathedral and the church of St John's with its medieval ruins. The term 'Saxon' was used sweepingly at the time to include buildings that were actually Norman in origin and Cuitt's use of 'Saxon and Gothic' reflects the increasing interest in Regency England with Britain's architectural history.

In Chester, he combined this with a desire to record the unique historic architecture, which he felt was at risk of being 'sacrificed' to make room for rapid development in the city, writing in 1808, 'it is to be regretted that many most curious specimens of [Chester's] ancient buildings have perished, neglected and forgotten.'

The cathedral, for example, was 'in a very decayed state' (as described in John Pigot's 1816 work), prior to restoration later in the nineteenth century. One of Cuitt's cathedral etchings of 1810 shows the south porch, foliage sprouting from the masonry, overgrowth creeping up the side and a dust heap piled high to the left of the door. The people gathered by the dust heap are patently uninterested in the medieval architecture towering above them. At the same time, Cuitt has paid close attention to the detail of the carvings above the door and around the windows, making full use of the delicate etched line.

But Cuitt didn't just draw and etch Chester. From there, it was a relatively straightforward journey into North Wales, where he depicted some of the many castles that pepper the landscape. His interior of Conwy Castle's Great Hall takes a low viewpoint from the southwest, looking up from the cellar floor, the whole structure overpowering the viewer.

The picture, with the whole structure almost overwhelmed by ivy growth, is a notable example amongst many of Cuitt's scenes which reassert nature on monumental ruins. Cuitt may have exaggerated somewhat for effect, but we know that such places were significantly more overgrown than they are today, when they are managed by conservation bodies such as the National Trust and English Heritage. Eighteenth-century notions of the 'sublime', with its associations of gloom and fear, are also evident in this etching. Cuitt clearly found etching an ideal medium for this purpose, with its dramatic gradations of light and dark.

Cuitt published Six Etchings...of Select Parts of Castles in North Wales in 1813, dedicating it to the MP Sir Watkin Williams Wynn, one of the largest landowners in North Wales at the time. This was a shrewd move. It secured Wynn's patronage and almost certainly influenced others in his circle to purchase Cuitt's prints.

Cuitt's artistic and financial success was due in part to his ability to use the early nineteenth-century art market to his advantage. As a print medium, etchings can be reproduced and therefore distributed more widely, unlike a unique art form such as drawing or painting. Cuitt cultivated lists of subscribers, who would commit to purchasing his etchings before they had been printed. It is important to note, however, that Cuitt aimed his etchings at a wealthy elite rather than a mass market.

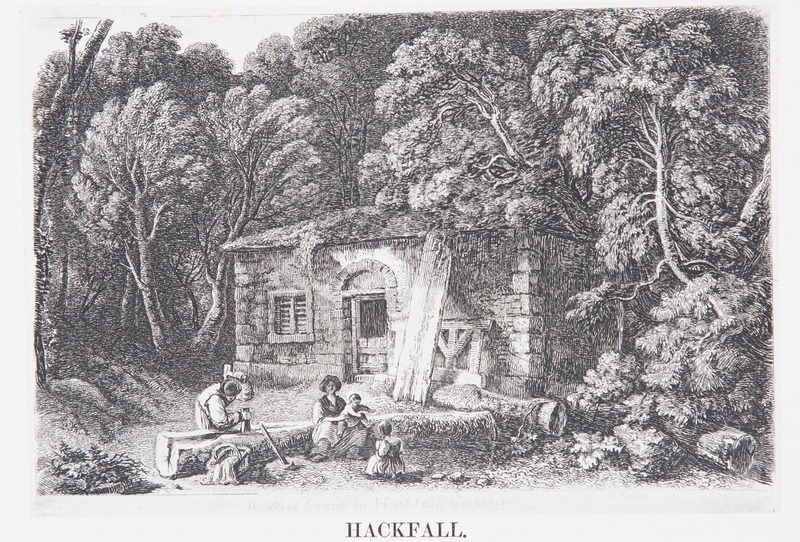

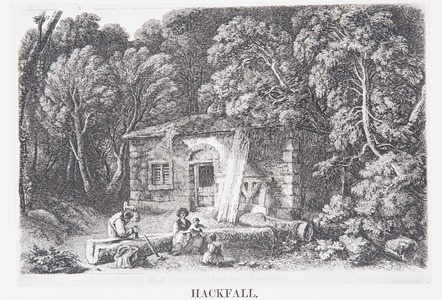

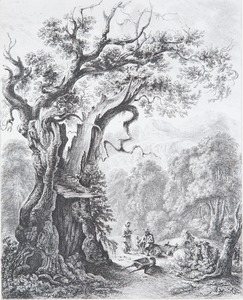

In contrast to these wealthy landowners, and certainly to the grand albeit neglected castles and cathedrals that were his usual fare, Cuitt's love of the ruin was also provoked by the ramshackle and decaying houses, sheds, pigsties and mills he found in his ramblings around Chester, North Wales and Yorkshire.

In 1816 he published Twelve Etchings of Picturesque Cottages, Sheds Etc. Drawn and Etched by George Cuitt. The term 'picturesque' in the title once again plays into a wider cultural concern, this time with attractive landscapes dotted with arching trees, sinuous rivers and a suitably run-down building to provide interest. There is something compelling in the fact that Cuitt chooses these buildings as the focus of some of his etchings, paying close attention to their different patterns, shapes and textures.

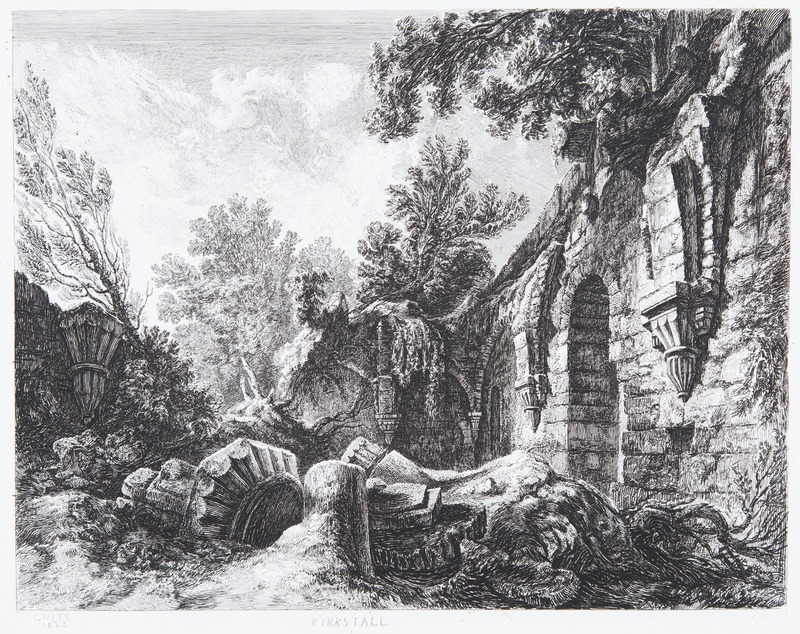

Cuitt returned to his native North Yorkshire in 1821, moving to Masham. Here he produced what is considered his finest work: several series of etchings focusing on the region's ruined abbeys. These sites had been left in ruins following the dissolution of the monasteries by Henry VIII in the sixteenth century.

Cuitt was not alone in his fascination with ruins. The eighteenth century had seen an explosion in 'ruin hunting' with artists, writers and tourists seeking inspiration and enjoyment from them. The craze reached its height in the Romanticism of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Susan Owens writes: 'What now began to grip people's imaginations was the intensely romantic atmosphere to be found in ruined abbeys and priories, and the potential of these sites to offer precious insights into the medieval past.'

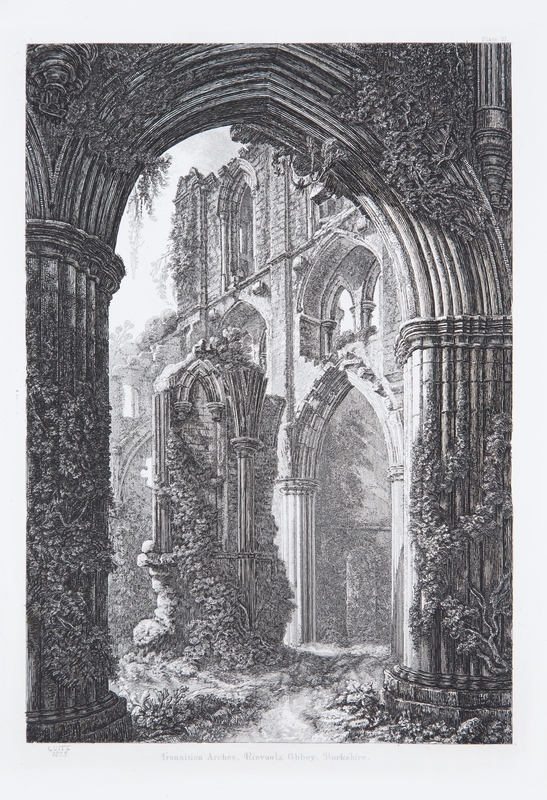

Cuitt's views, however, are by no means the usual ones. As ever, he was highly selective in what he depicted, combining unusual viewpoints with his typical close attention to detail. While Cuitt is certainly interested in them as relics of the past, he is more compelled by the contemporary relevance of these sites in the landscape.

Image credit: Grosvenor Museum

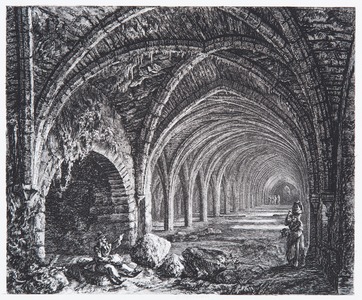

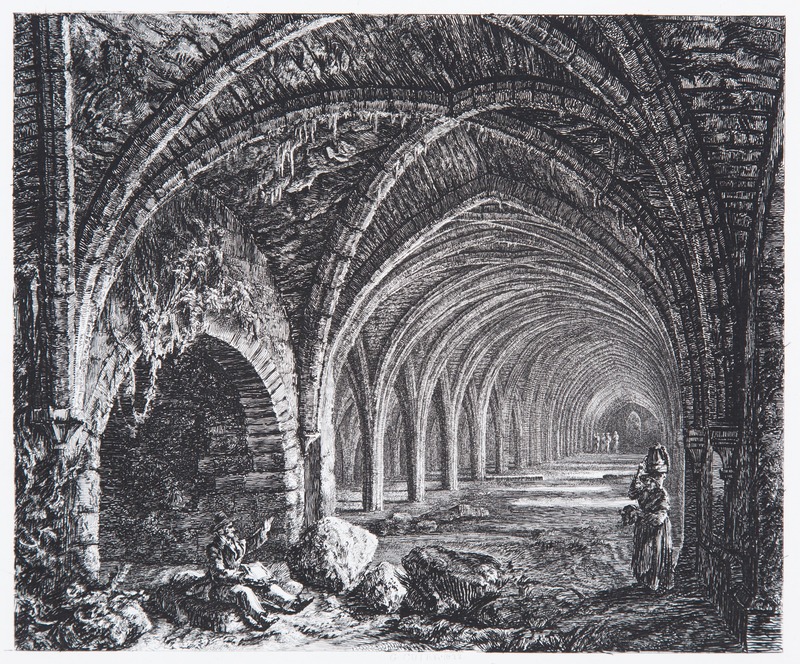

Cellarium, Fountains Abbey (The Cloisters) 1822

George Cuitt the younger (1779–1854)

Grosvenor MuseumCuitt's etchings of the abbeys of North Yorkshire are masterclasses in control of the etched line – to create shade, depth and detail. He confidently exploits its capacity to render architectural subjects with vibrancy and liveliness, whilst retaining the accuracy of a topographical draughtsman. The 'Abbeys' series is perhaps the clearest evidence of Cuitt's adoption of the visual language of the Romantic movement – dramatic contrasts, the persistence of nature and an individual perspective.

His etching of the South Transept of Rievaulx Abbey stands out for its handling of spatial complexity, recession and use of light and shade. It shows the view from the choir to the south transept through the second arch of the crossing. Cuitt uses the arch in the foreground to frame a sequence of receding elements which lead the eye ever deeper into the picture whilst adjusting the etched line and the biting of the plate to deepen the perspective.

Cuitt's plates are always highly worked, but usually with fine lines to maintain their delicacy. The density of Cuitt's shadows belies the detail within them. Look closely, and there is often something emerging from the darkness.

Cuitt retired from etching in 1840, for reasons that are not entirely clear but which probably have something to do with the intense physical labour it involved, as well as its many pitfalls. He sold his plates and copyrights to the London publisher Nattali who brought out a collected volume of Cuitt's work, called Wanderings and Pencillings Amongst Ruins of the Olden Times (1848). This, and the second edition of 1855, helped make Cuitt's work accessible to a new and wider audience.

Today Cuitt's distinctive work is relatively little known but ripe for reassessment. His ability to combine architectural accuracy with his unique Romantic vision and his mastery of the etching technique means that his prints deserve close and repeated attention.

Jessie Petheram, Assistant Curator (Art), West Cheshire Museums

'The Romance of Ruins: the Etchings of George Cuitt' is at the Grosvenor Museum, Chester, until 12th January 2025

Further reading

Peter Boughton and Ian Dunn, George Cuitt (1779–1854) – 'England's Piranesi': His Life and Work and a Catalogue Raisonné of His Etchings, Chester University Press, 2022

George Cuitt, advertisement for Eight Etchings of Old Buildings in…Chester, in the Chester Chronicle, 25th November 1808

Susan Owens, Imagining England's Past, Thames & Hudson, 2023

John Pigot, History of the City of Chester from its Foundation to the Present Time; Illustrated with Five Etchings by G. Cuitt, Chester, 1816