George Chinnery (1774–1852) was perhaps the most prominent and best known western-style illustrator and painter in Asia and the Far East during the first half of the nineteenth century. London born to an artistic family, he showed his talent in portrait painting at a young age and had his first work exhibited at the Royal Academy of Arts in 1791 at the age of 17. His portraits, among them a few self portraits, are now in the collections of the National Portrait Gallery, The Fitzwilliam Museum, British Library, Tate and many other institutions and museums in Britain and abroad.

In 1802, Chinnery left Britain and never returned. He was 28. He first went to Ireland and from there to India and finally settled in Macau where he lived for 25 years until his death. It was in Macau that he produced his best and most successful works.

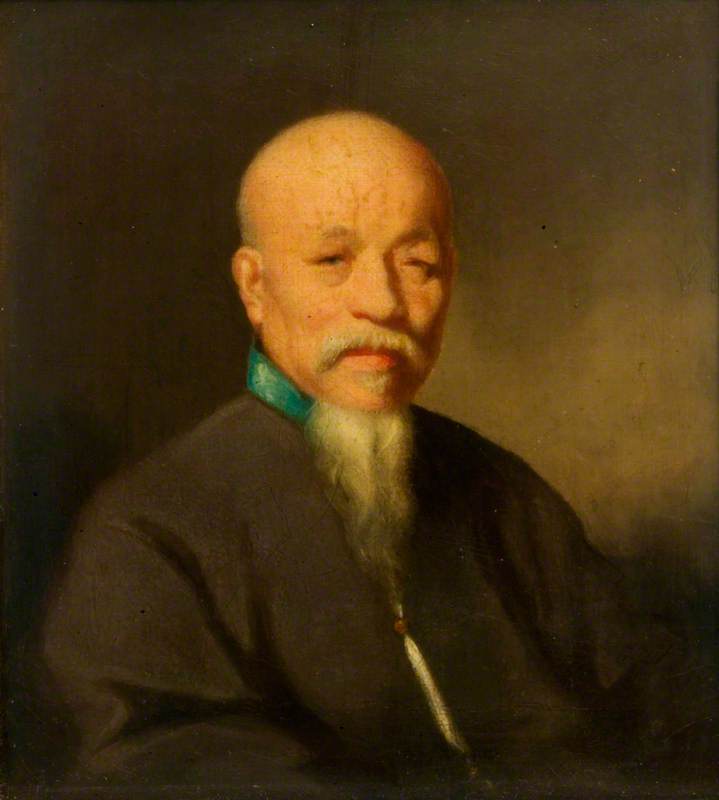

Portrait painting was Chinnery's main livelihood. In Macau, his portraiture included local celebrities, Chinese merchants and captains of industry. One painting that depicted a Chinese man in an official robe with a painted landscape screen as the backdrop is in the collection at Tate. The man in the painting was a Hong Chinese merchant of a quasi-official status named How Qua, or Wu Bingjian 伍秉鉴 (1769–1843), who was one of the richest Chinese in his time.

Originally from Fujian province, southeast of China, How Qua's family settled in Guangdong province in the early eighteenth century as tea planters. Before long, his father took to the trade and became a merchant, one of the very few who was licensed to conduct trade with westerners at the time. Business flourished and in 1783, Wu's father set up his own trading company named 'YiHe Hang' or YiHe Merchants (怡和行), and gave himself a merchant name: 'Haoguan' 浩官 meaning 'the Hao official', or How Qua in Cantonese.

In 1801, at the age of 32, Wu Bingjian inherited the business and the merchant trading name from his father. Under his management, the family business expanded to banking, investment and insurance. Benefitting from his quasi-official status, he amassed a large fortune through his close business connections and dealings with the western merchants. He was once the biggest banker and creditor to the East India Company.

Although Chinnery lived mainly on portrait commissions in Macau, it was his sketches and landscape paintings that left a lasting legacy for future generations. Fascinated by the people and the sweeping panoramic scenes across the bays and peninsulas of Macau, Chinnery often made early morning sketching expeditions to study and record everyday life. He had an innate curiosity for people and made intimate studies of street barbers, blacksmiths and porters as well as general street scenes. He accumulated a large repertoire of etchings and drawings.

Image credit: National Trust Images

Chinese Barber Outside the American Factory in Canton (Guangzhon), China 1826

George Chinnery (1774–1852)

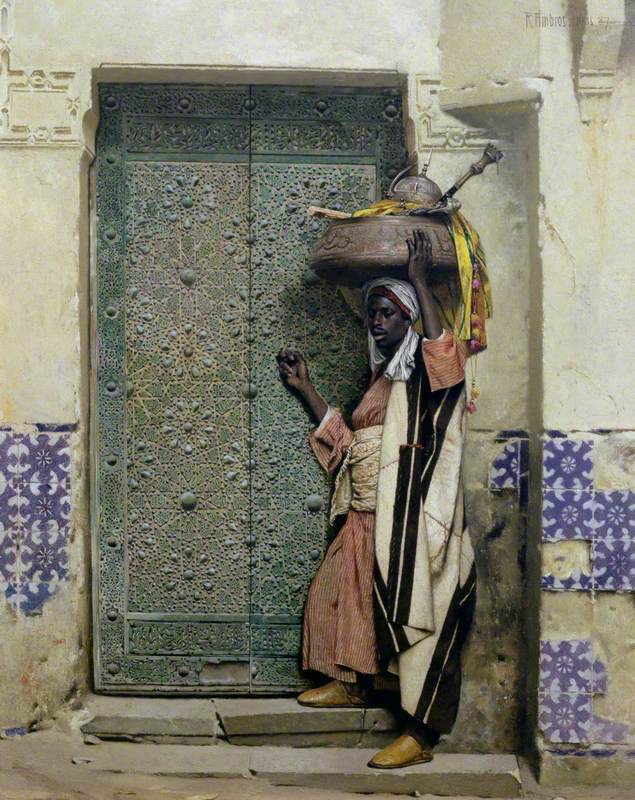

National Trust, Coleton FishacreAt Coleton Fishacre in Devon is this painting of a Chinese barber sitting on a stool with his tools around him. The painting now belongs to the National Trust. There are many study images of a barber in Chinnery's sketch books. Shown here are two sketches in the collection of the British Museum, one of a barber carrying his tools on his shoulders and the other his tools only.

Image credit: British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Two drawings by George Chinnery

'A Barber's Paraphernalia' and 'A Barber Carrying His Requisites; Walking to Right, Wearing Large Brimmed Hat', 1775–1857, graphite on paper by George Chinnery (1774–1852)

In the Qing dynasty (1644–1911) in China, a Chinese man had to be clean shaven with no beard, no moustache on the face and no hair on the front of the head. Only near the back of the scalp was he allowed to grow a 'queue' of hair which was often arranged in an organised plait. Not surprisingly, there was a constant demand for the services of a barber. It was estimated that 7,000 barbers were operating in Canton and Macau in Chinnery's time, most of them on the street. Thus, making study images of a barber must have been a fairly easy thing to do for Chinnery.

The two paintings of street scenes at Macau shown below are now in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum. The British Museum has in its collection the study sketch made by Chinnery of almost exactly the same spot and same scene.

They show us vividly a market corner of a street centred around a food stall with people eating, standing or walking about. The baroque-style façade in the background was part of the Santo Domingo church in Macau, a sixteenth-century building and still one of the architectural glories of the city.

© George Chinnery. Image credit: British Museum, available under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license

Marketplace, Macau

c.1838–1839, pen & brown ink with brown wash, touched with graphite on paper by George Chinnery

Chinnery lived in an age before the advent of photography. His lively and atmospheric drawing of life in Macau came from his direct experiences – he was often up at five o'clock in the morning and went out to make sketches. He was so interested in the world around him that he would often return to the same subjects again and again when he made sketches and drew the same scenes multiple times.

With the portraits of the people and the paintings of everyday scenery, Chinnery left us intimate glimpses of life in Macau. Thanks to him, we know what Macau, parts of Canton and Hong Kong looked like in the first half of the nineteenth century.

Mei Xin Wang Farrell, China resource specialist at the British Museum