The easy representation of ourselves and our loved ones is something we take for granted. Historically, however, the opportunity to be depicted was an elite privilege. Few artists in the early modern period had the time or the inclination to make portraits of their relations. But Thomas Gainsborough was the exception to this rule.

Despite his famous antipathy towards portraiture, and the clients whose 'damn'd faces' distracted him from his love of landscape, he painted and drew over 50 portraits of his extended family. These include some of Gainsborough's best-loved works, as well as many that are little known and rarely exhibited. Seeing them all together provides new perspectives on his life, motivations and work.

Much like the family albums that we create today, the purpose of these pictures was to document the people with whom Gainsborough shared his life. Yet if they provided an outlet for his affections, they also served his social and professional ambitions; while some are highly intimate in character, the majority speak more clearly of a middle-class family's aspirations to gentility. The stage is set by Gainsborough's first self-portrait with his family.

Portrait of the Artist with his Wife and Daughter

about 1748

Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788)

Painted when he was about 20, shortly after his marriage to Margaret Burr, it depicts the couple as fashionable gentlefolk at ease in the countryside. The composition is a conversation piece, a portrait type showing small-scale full-length figures that was popular in the middle decades of the eighteenth century. Here we can find the earliest evidence of the Gainsboroughs' determination to assert a status equal to his affluent patrons – a bold assertion, given the relatively humble status of artists at that time.

Many of Gainsborough's family portraits remain unfinished to some degree. There were practical reasons for this, of course, but something more was implied: a lack of finish would distinguish private from commissioned works. All of these unfinished paintings remained within the family, apart from one notable example.

The Painter's Daughters chasing a Butterfly

probably about 1756

Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788)

On leaving Suffolk for Bath in 1759, Gainsborough gave the tender painting of his young daughters chasing a butterfly to the Reverend Hingeston, headmaster of Ipswich School. This was a strategic act. Gifts strengthened bonds with friends and ensured that Gainsborough remained visible among an audience primed for future patronage.

The same picture also reveals how the artist used his 'family album', and especially the double portraits of his daughters, as opportunities to experiment with new techniques and genres. Never before had Gainsborough attempted to place full-size figures in motion in a landscape, or to demonstrate such freedom in his brushwork. But if these were to become standard markers of his signature style, he would hardly ever again try to imbue a portrait with such depth of meaning: Mary restrains her younger sister Margaret who reaches out towards the butterfly that has settled on a thistle – thus symbolically indicating the risks that attend the heedless pursuit of pleasure, as well as pointing to childhood as a transient and highly vulnerable stage of life.

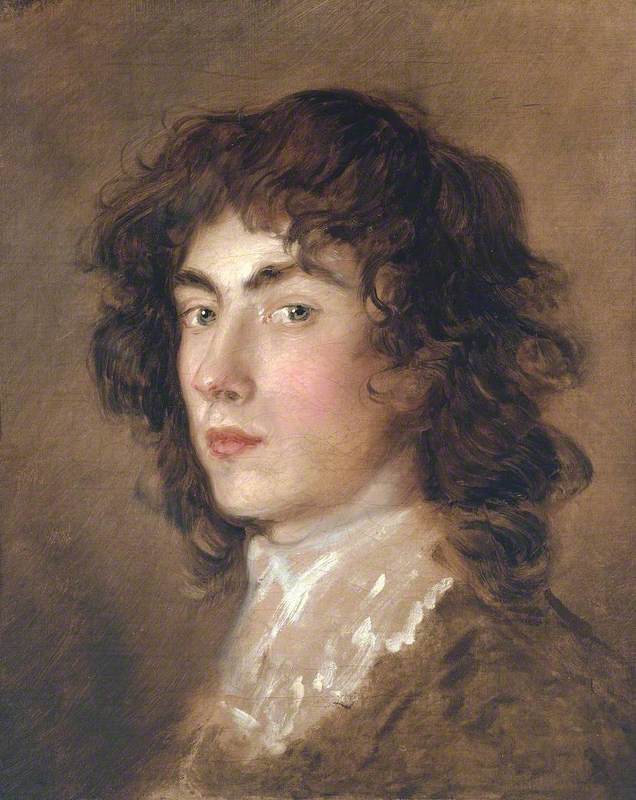

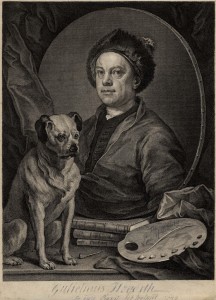

By this time the family had moved from Suffolk to Bath, where they were to live from 1759 to 1774. Here Gainsborough came to maturity as an artist. Able to study the Old Masters in local aristocratic collections, he became acquainted with the work of Sir Anthony van Dyck, whose example would guide him for the rest of his life. The oval portrait of his nephew and apprentice Gainsborough Dupont, sporting the same Van Dyck-style outfit as The Blue Boy (now in The Huntington Library in California), offers a bravura display of Gainsborough's talent.

Gainsborough Dupont (1754–1797)

1773

Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788)

It took him less than one hour to transform the son of a Suffolk carpenter into a gilded youth who looked like he had stepped straight out of the court of Charles I. If this was a demonstration of the transformative power of Gainsborough's virtuosity, it also reflects his determination to elevate portraiture to the level of great art.

The same ambition informs Gainsborough's most complex and compelling depiction of his wife, perhaps painted on the occasion of her 50th birthday, around three years after the family's move from Bath to London.

Margaret Gainsborough, née Burr (1728–1797)

c.1778

Thomas Gainsborough (1727–1788)

In this striking image, as she holds back her mantilla and gazes directly at her husband, Margaret strikes a pose based on the classical statue of the goddess Juno – the irascible spouse of the philandering Jupiter. If this betrays a hint of criticism of his wife, the joke was also on him. The painting nevertheless witnesses Gainsborough's appreciation of the woman who ran his portrait business, liaised with his clients and raised his family. He portrayed her at least nine times over the course of their long, and sometimes difficult, marriage – only his daughters featured more.

Dupont, who joined Gainsborough's household as a boy and in effect became his surrogate son, makes several appearances in the 'family album'. The final occasion was during Gainsborough's dying days, when the artist placed an old unfinished portrait of his nephew on his easel. Here this small canvas assumed the deeply meaningful role of its creator's 'last picture', signaling his regret at leaving life without having realised the full extent of his talent. But the study of Dupont also communicated two other important messages to posterity. The first expressed Gainsborough's desire to be remembered alongside Van Dyck, who was his highest object of emulation. At the same time, the gesture nominated Dupont as his artistic heir.

Elevating a likeness of Dupont to a position of such prominence also implicitly acknowledged a greater truth. We usually tend to think of artists as autonomous social actors – yet for all of Gainsborough's efforts to cultivate his artistic individuality, his 'family album' tells a different story: of how a network of relations supported a painter's rise to fame.

David Solkin and Lucy Peltz, exhibition curators of 'Gainsborough's Family Album' at the National Portrait Gallery, London

A version of this article first appeared in the autumn/winter edition of Face to Face, the magazine for National Portrait Gallery members

The exhibition ran from 22nd November 2018 to 3rd February 2019, curated by Professor David Solkin, The Courtauld Institute of Art, with the support of Dr Lucy Peltz, National Portrait Gallery