Following the death of HM Queen Elizabeth II, the airwaves have been filled with images of ceremony, pageantry and grief.

Every part has been televised and live streamed – the transportation of the coffin from Balmoral to Edinburgh, and then on to London, and the journey from Buckingham Palace to Westminster Hall, where the lying-in-state has taken place before the funeral in Westminster Abbey and the committal service in St George's Chapel, Windsor. The only part not publicly broadcast was the private burial.

The queue associated with the lying-in-state, and the presence of the king and royal family, has been highly scrutinised on TV, the press and social media. It is a mark of how much changed during Elizabeth II's reign that she is the first monarch to be commemorated in the UK in the digital age.

The last monarch to have a state funeral was the late Queen's father, George VI, in 1952. His lying-in-state not only predated live streaming, but even mass television viewing (which would be kickstarted by the Queen's Coronation in 1953) – but it was recorded in this painting.

In 1936, when George V died, as part of the lying-in-state, his sons – the new king Edward VIII, the Duke of York (later George VI), the Duke of Gloucester and the Duke of Kent – took part in a vigil. This was recorded by the artist Frank Beresford.

In 1936, my grandfather, Frank E. Beresford, a professional artist, went to see the lying-in-state of King George V. He was moved by the scene & asked permission to set up his easel and paint it. From this emerged his painting, The Princes' Vigil, which was bought by Queen Mary. pic.twitter.com/SDcoLNzodh

— James Bartholomew (@JGBartholomew) September 14, 2022

This 'Vigil of the Princes (and Princesses)' has been replicated by the Queen's children and grandchildren during the lying-in-state period, and was also seen during the Queen Mother's lying-in-state in 2002.

There is very little in terms of artworks in public collections that depict these events. Far from a centuries-old tradition, Edward VII was the first monarch whose lying-in-state took place in Westminster Hall, supposedly inspired by Prime Minister William Gladstone's in 1898. The hall had been used as law courts until the 1880s, and previous monarchs had lain-in-state elsewhere – sometimes where they died.

But what is lying-in-state? Essentially it is when the deceased person lies in a state building, before a state or ceremonial funeral, in order for others to pay their respects.

The elements can be seen in much earlier artworks – for example, the catafalque (the platform on which the coffin rests) is visible in this work, which depicts the funeral of the Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand II in 1637.

Perspective View of the Catafalque at the Funeral of Emperor Ferdinand II

1637

Stefano della Bella (1610–1664)

More recently, Winston Churchill was granted a state funeral in 1965 – the last state funeral in the UK before the Queen's. His lying-in-state was captured by several artists.

The Lying-in-State of Sir Winston Churchill

1965

Terence Tenison Cuneo (1907–1996)

The Lying-in-State of Sir Winston Churchill (1874–1965), Westminster Hall

c.1965

Mary Young

The Lying-in-State of Winston Churchill in Westminster Hall, 1965

1965

Alfred Egerton Cooper (1883–1974)

At the time of his death he was widely seen as a national hero, and the footage of his funeral from newsreels is reminiscent of the more recent images we have seen in the aftermath of the Queen's death. The cranes being lowered along the Thames as a mark of respect is particularly notable.

Other non-royal state funerals are quite rare. One such example is that of Edith Cavell, the nurse who was executed during the First World War.

The Funeral Service of Edith Cavell at Westminster Abbey, 15 May 1919

1919

William Hatherell (1855–1928)

Another non-royal to have the honour of a state funeral was naval hero Lord Nelson, whose funeral procession along the Thames must have seemed particularly fitting.

Nelson's Funeral Procession on the Thames, 9 January 1806

1807

Daniel Turner (active 1782–c.1828)

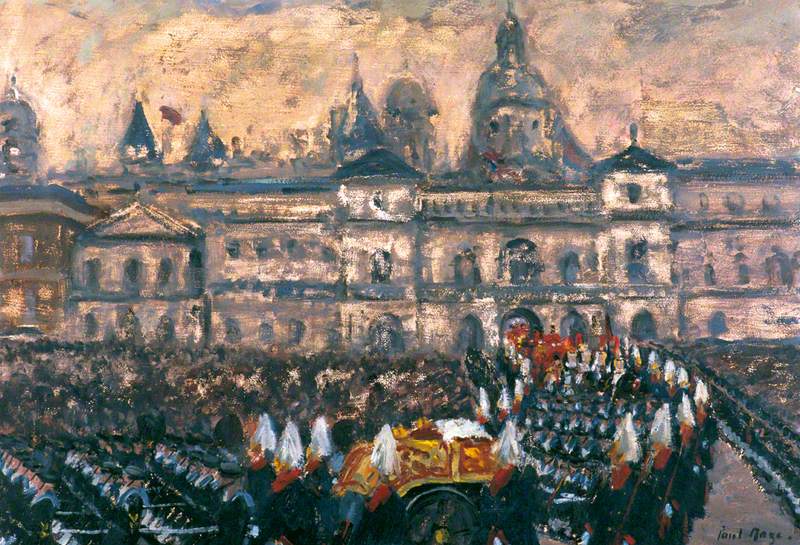

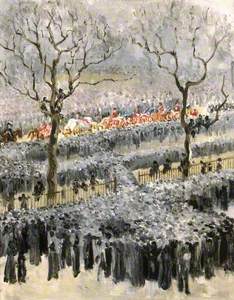

Moving back to royalty, there are also artistic depictions of funeral processions, such as this painting of Queen Victoria's passing through Hyde Park.

The Funeral Procession of Queen Victoria Passing through Hyde Park, London

1901

Mary Edith Durham (1863–1944)

Other funerary traditions associated with royalty have been depicted, such as this gun salute, also dating from the time of Queen Victoria's funeral.

Last Minute Gun Firing from Elizabeth Castle, Queen Victoria's Funeral

1901

William Honnywill Hall (1851–1905)

Before a certain point, funerals of monarchs were not routinely recorded in art by eye-witnesses – but artists later sought to romanticise or reconstruct the events. The aftermath of Charles I's execution was depicted by Ernest Crofts, who specialised in paintings of the English Civil War, despite working in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. His 1907 work of Charles's funeral at Windsor in 1649 combines theatrical effect with historical accuracy.

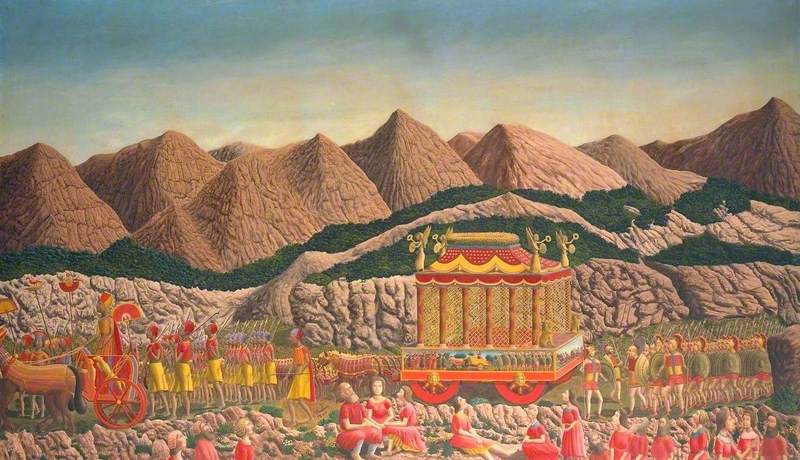

Funeral of Charles I, St George's Chapel, Windsor, 1649

1907

Ernest Crofts (1847–1911)

Crofts visited Windsor, 'so as to be correct as I possibly could', and also studied a seventeenth-century view of the castle. Noblemen in mourning had carried the coffin to Windsor Chapel, where the Bishop of London was waiting to perform the service. However, the castle governor, Lord Whitchcot (seen on the far right with a group of attendants), denied the king a burial according to the Book of Common Prayer and he was interred without ceremony.

For the contemporary viewer, Crofts's painting would have been rich in romantic and patriotic associations.

Going further back into history, in the middle of the First World War Harry Morley imagined the burial of Henry I at Reading Abbey in 1136.

A pivotal moment in English history, it marked the start of a bitter civil war, but also celebrated Reading as an important town. The lying of the monarch on a bier or catafalque, the candles and the heraldry all conjure a romantic notion of the past.

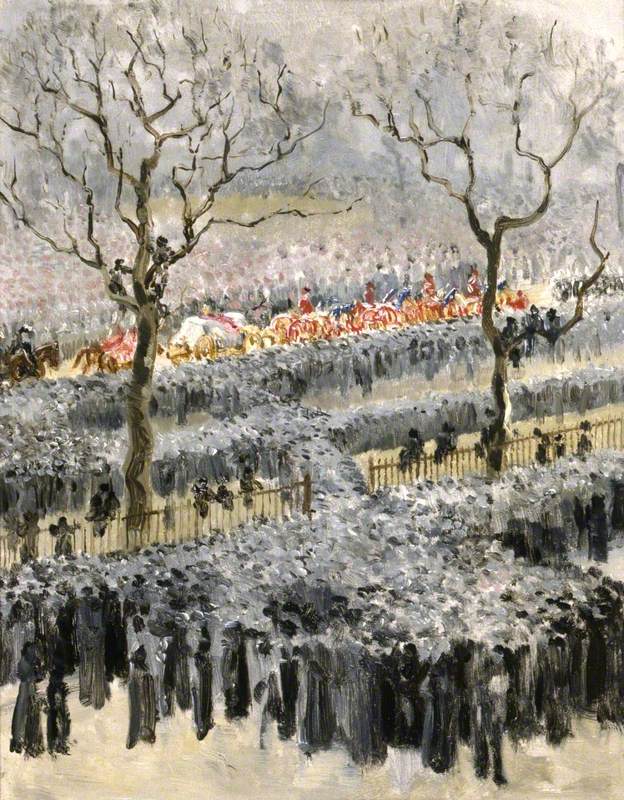

Going back even further, the French naïve painter André Bauchant imagined the funeral procession of Alexander the Great, which took place in 323 BC. Although based on an actual account, there are obviously large parts of guesswork in the finished piece.

The Funeral Procession of Alexander the Great (Les Funérailles d'Alexandre-le-Grand)

1940

André Bauchant (1873–1958)

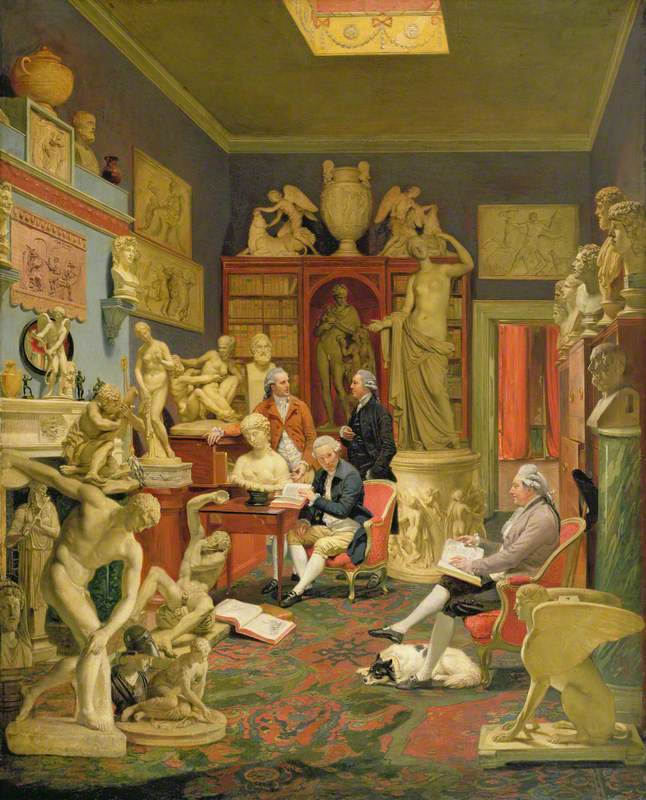

But not all depictions of funerals are grand ceremonial or state occasions. The painter J. M. W. Turner died at his cottage in Cheyne Walk, Chelsea, on 19th December 1851 and soon afterwards his body was transferred to his house in Queen Anne Street, where it was placed in the centre of the gallery, right among his own paintings. The artist George Jones has captured this moment.

Turner's Body lying in State, 29 December 1851

post 1851

George Jones (1786–1869)

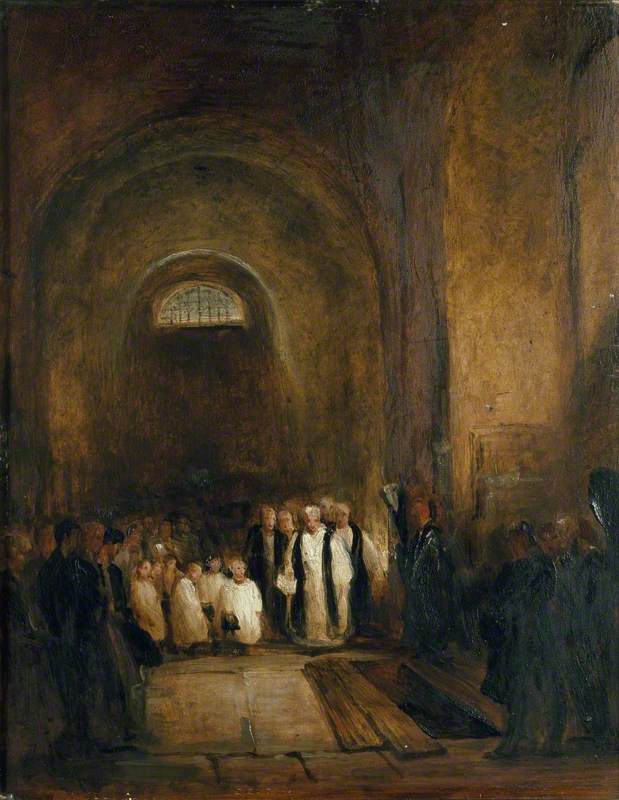

Turner's funeral took place on 30th December 1851 and in another work Jones portrayed the burial in the crypt of St Paul's Cathedral.

Turner's Burial in the Crypt of St Paul's

post 1851

George Jones (1786–1869)

Whether royal or not, state, ceremonial or a much simpler affair, all funerals are important to those who attend. Marking the passing of a soul, and the continuation of life for others, is universally important across time and cultures.

In the case of Elizabeth II, the state funeral of such a long-lived monarch will live long in the nation's collective memory, whether portrayed in art or not.

Andrew Shore, Head of Content at Art UK