Distance has become a lingering presence in our daily lives, now acting as a prerequisite for all face-to-face interactions. The limitations enforced by COVID-19 have pervaded the inception of a new decade – so it's no surprise that my hour-long conversation with Ghanian photographer and trailblazer, James Barnor (b.1929) occurs over the phone and not in his west London home.

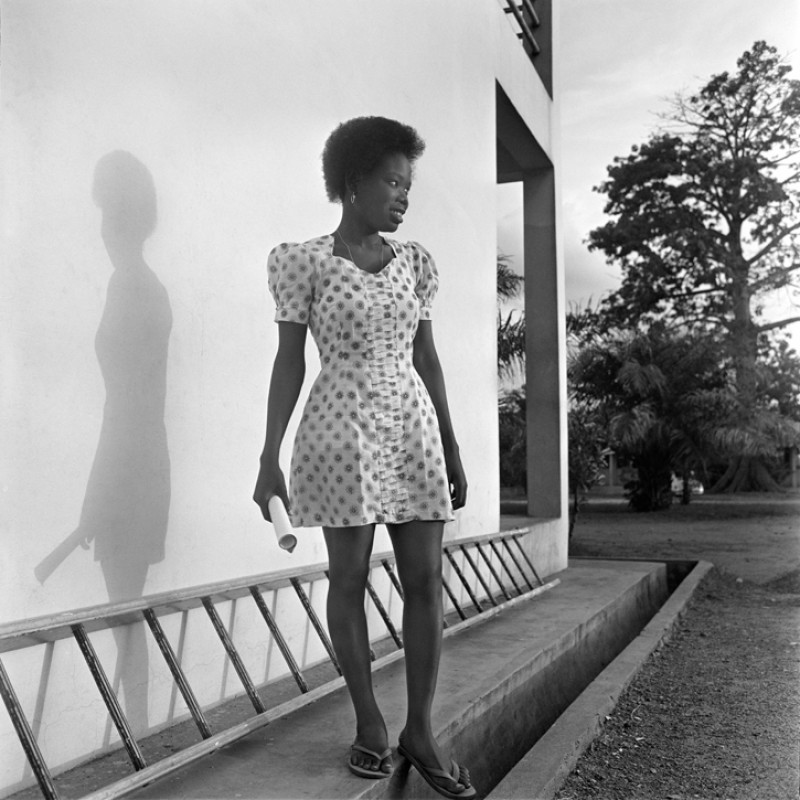

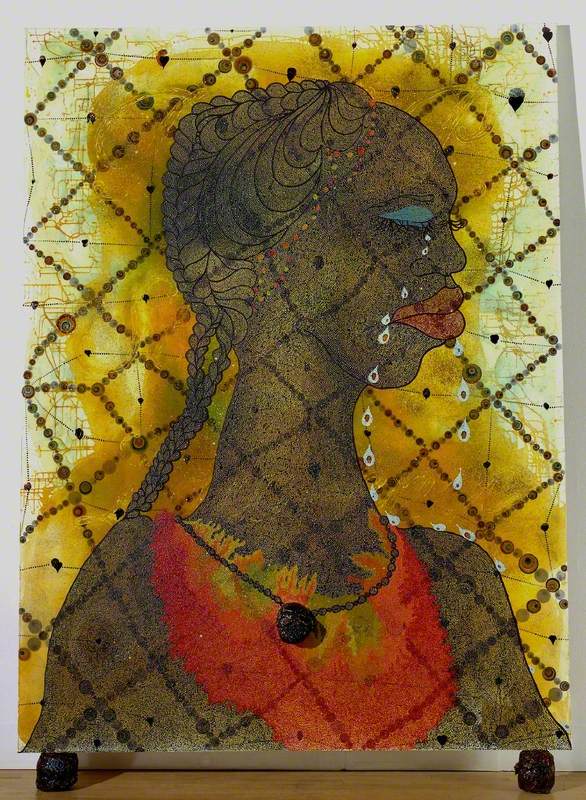

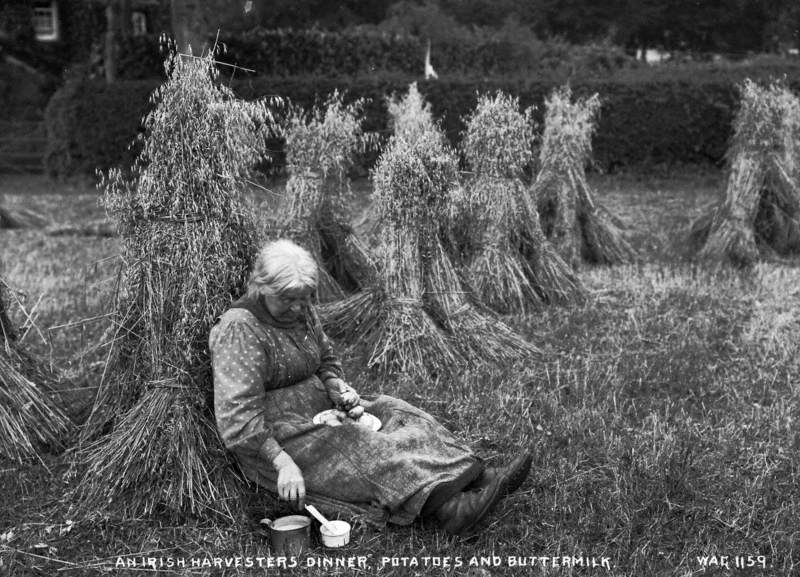

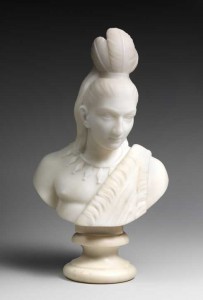

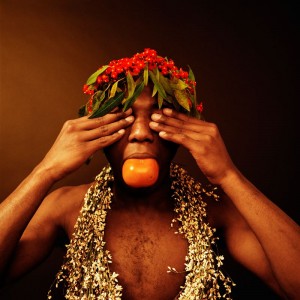

AGIP Calendar Model

1974, photograph by James Barnor (b.1929)

Upon commenting on his desire to converse in person, he decides this will have to do, given the circumstances. Barnor is at once warm, solicitous, and familial – so the call naturally begins with him setting the scene for me: 'My council flat overlooks the river, and the view is wonderful. It almost tempts me to pick up my camera again', he says with a gentle laugh. I respond by telling him I wish I was there to see it.

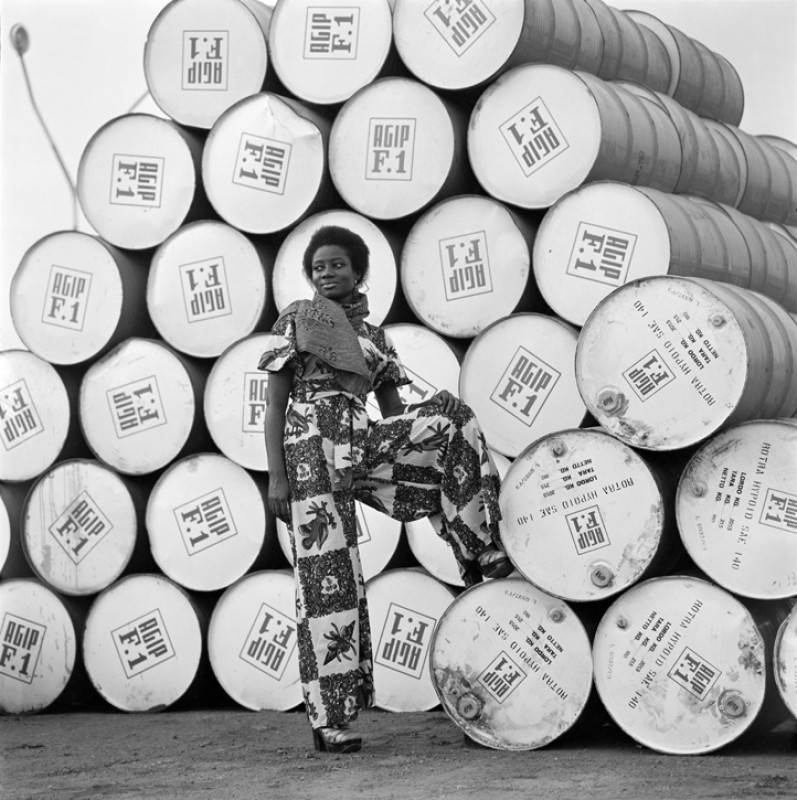

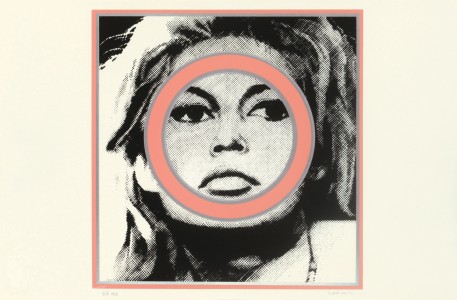

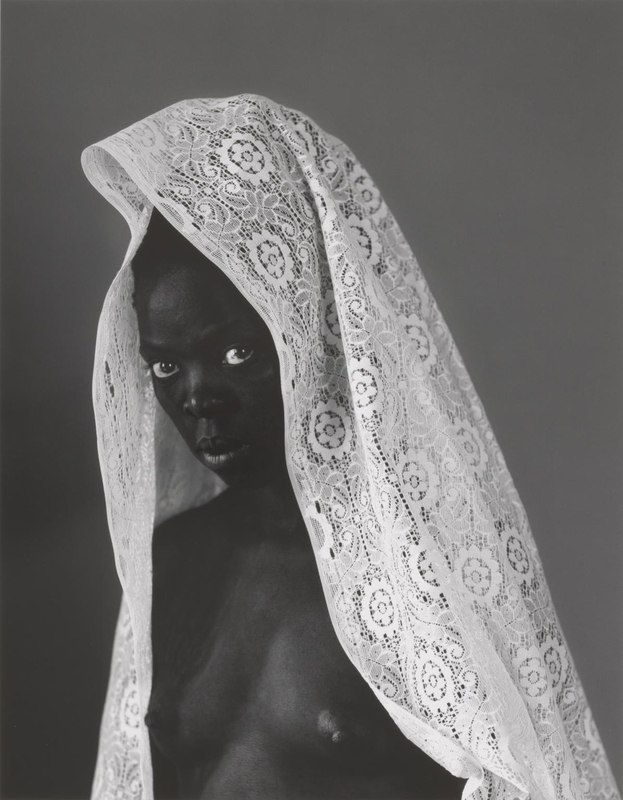

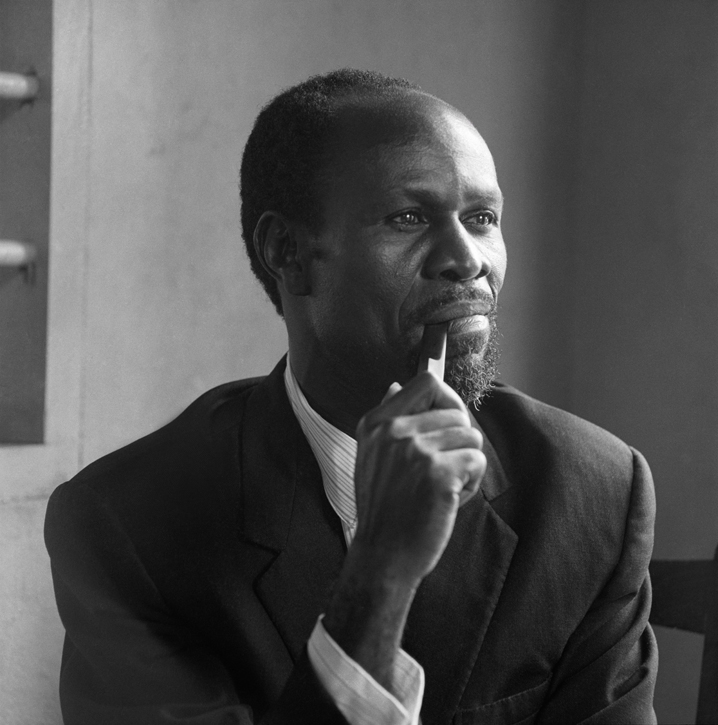

James Barnor

2016, photograph by Jonathan Greet

Now happily retired, Barnor is merely a spectator to the success he achieved in the 1950s as a photojournalist and studio photographer. 'Gone are the days when I would run off on assignment, capturing life in Ghana and London. I often take pictures on my iPad now', he admits.

This year, in celebration of Barnor's 91st birthday, the Serpentine Gallery was due to exhibit a major survey of the photographer's extensive archive. However, due to the nature of the pandemic, the show has been postponed until 2021. Barnor assures me that he and the team at Serpentine Gallery are adding to the exhibition collection daily, and that they envision the exhibition will be even bigger and better once it opens.

Astonishingly, only at the ripe age of 80 did Barnor come to prominence as an artist. Critics have since described him as a 'man of firsts', which calls into question the overdue recognition of his work. He was the first to put Black-African women on the cover of well-known publications like the South African anti-apartheid title, Drum magazine, as well as introducing Ghana to colour processing on his return from England in the 1960s.

In reference to these milestones, the editor of Africa is a Country, Sean Jacob comments: 'James Barnor is to decolonising Ghana (and later to 1960s Black Britain) what Oumar Ly is to Senegal or Malick Sidibe and Seydou Keita were to Mali.'

In 1959, a fresh-faced Barnor left the coastal city of Accra, Ghana for London – a city in recovery from war and political upheaval. Unable to secure a job in commercial photography due to the colour of his skin, he began working in a factory to make ends meet. 'You could not come from Africa and go into British photography. There were no photography studios in London that would hire a Black assistant.

He continues: 'If you were lucky you'd secure an opportunity to work in a dark room – hidden from clients. So I went and made my own opportunities.' In Accra, Barnor was used to having an influx of people coming in and out of his Ever Young studio nestled in the district of Jamestown, whilst also working as a photojournalist for the Daily Graphic – a Ghanian state-owned newspaper.

However, in London the ambitious photographer found himself shooting multinational models in a city far from his own – allowing him to document the city's growing Black diaspora. This transition marked the beginning of a different type of practice, one that highlighted and celebrated the Black British 1960s in all of its colourful abstract patterns.

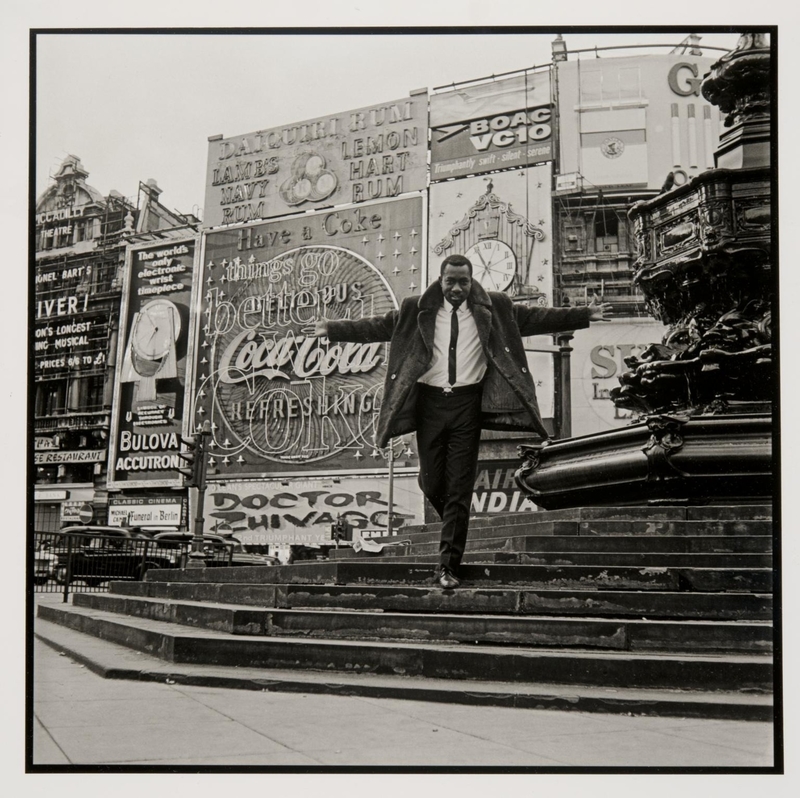

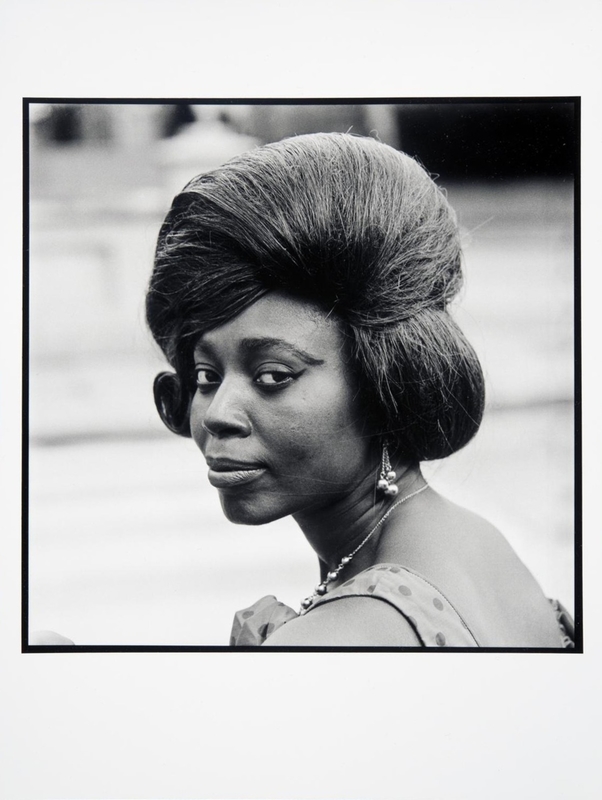

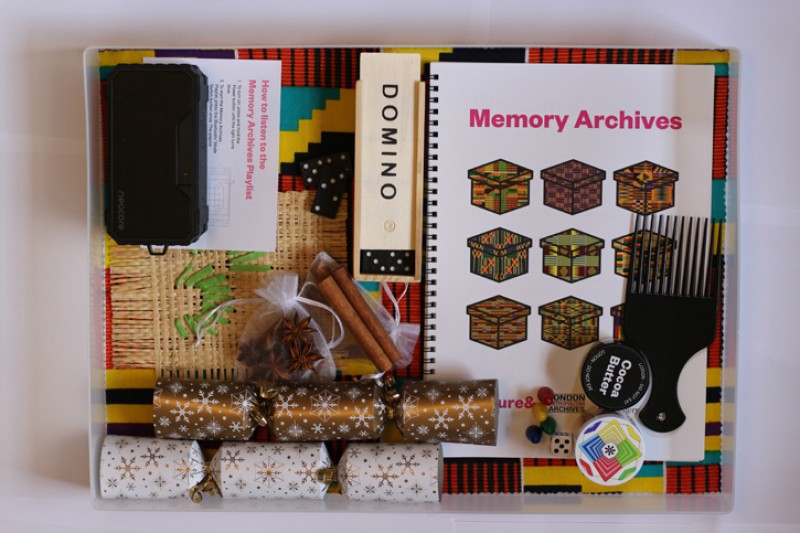

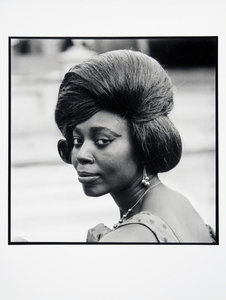

Erlin Ibreck at Trafalgar Square

1966–1967, photograph by James Barnor (b.1929)

With 10 years of experience behind him, he began shooting models like Erlin Ibreck for Drum magazine. When exploring Barnor's personal and professional London archives, the display of Black women is at once noticeable. On the topic of providing a much-deserved platform for Black women, Barnor said: 'At the time I didn't really think I was doing anything extraordinary, it was only later that I felt I'd been lucky the entire time.'

Barnor photographed models like Ibreck in quintessentially London locations like Trafalgar Square, and in front of the city's distinct red phone boxes to contextualise the location of his images. With a whole new community to tap into, Barnor describes how it felt to walk into his new playground: 'Everything was different in London – colour was different and that was at once exciting.'

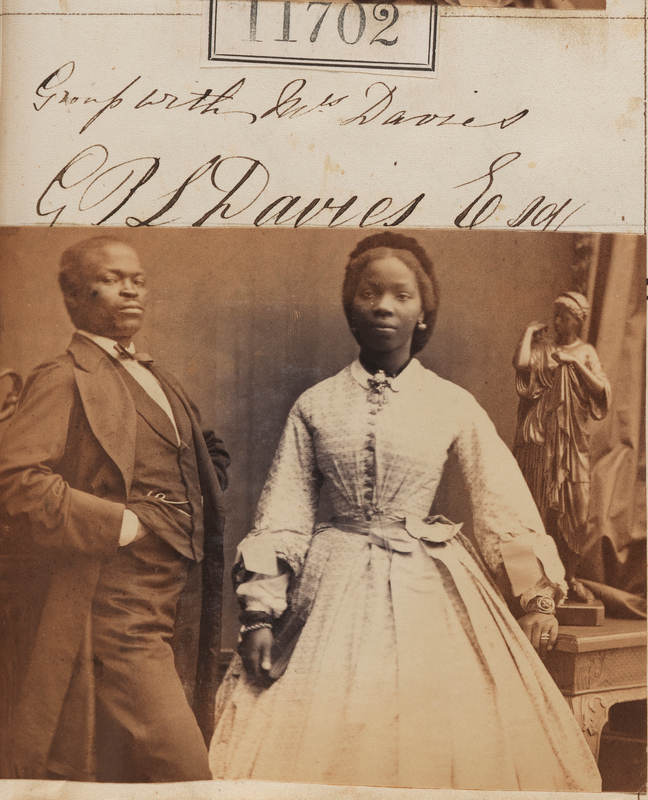

In the 1960s, post-war Britain was experiencing the first wave of migration, with many African migrants and members of the Windrush generation settling down in London. Onlookers began to notice that the city was mushrooming into the multicultural hub of Britain. In 1950, it was estimated that 20,000 Black people travelling from abroad resided in the United Kingdom. In contrast, by the end of the twentieth century, there were half a million Black Londoners alone. This period of transition coincides with Barnor's own country's fight for independence.

The photographer is best known for documenting Ghana 'on the cusp of independence' from British colonial rule in 1957 – marking a pivotal moment in its history, as Ghana became the first sub-Saharan African country to gain its independence from European colonisation.

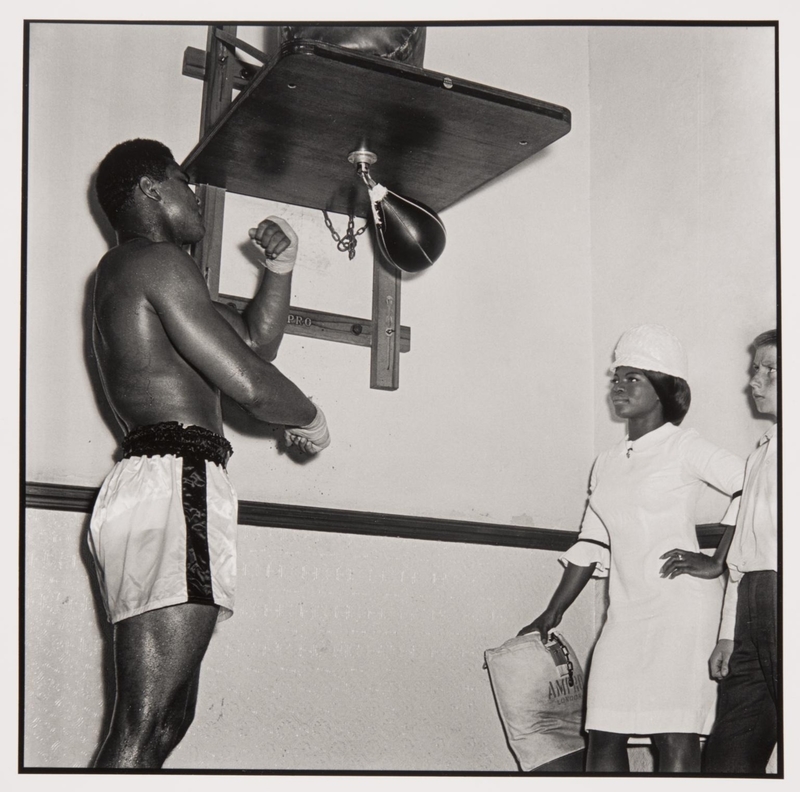

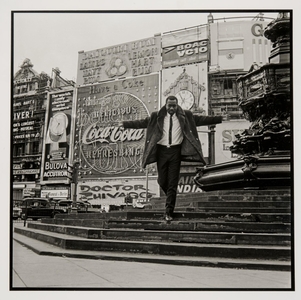

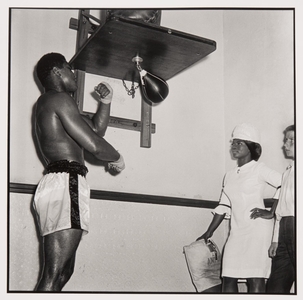

His expansive portfolio also displays iconic photographs of Kwame Nkrumah – Ghana's first president – as well as intimate shots of Muhammed Ali training in Earls Court and the BBC's first Black broadcaster, Mike Eghan, leaping from the steps of Piccadilly Circus' Shaftesbury Memorial Fountain.

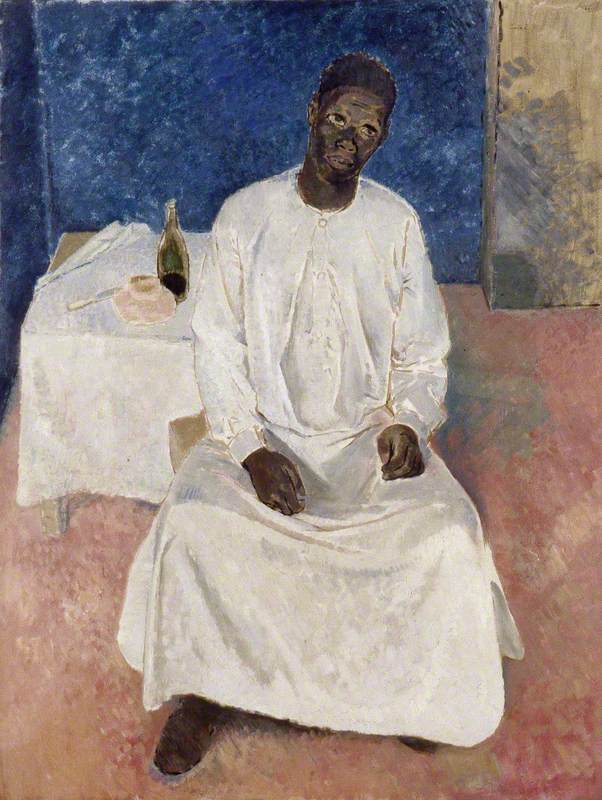

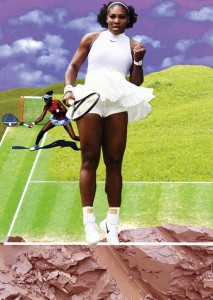

Osofo Dadzie

1975–1978, photograph by James Barnor (b.1929)

In 2007, curator Nana Oforiatta-Ayim took heed of Barnor's contribution to Ghana's visual arts scene and organised his first solo exhibition entitled 'Mr Barnor's Independence Diaries' at the Black Cultural Archives in Brixton, south London. Barnor's experience with colour processing and the pathway he forged for Ghana's newfound technicolour future was of particular interest to Ayim. On his return to Accra, Barnor brought with him an expansive fountain of knowledge in relation to shooting in colour, from which he acquired at Medway College of Art in Kent.

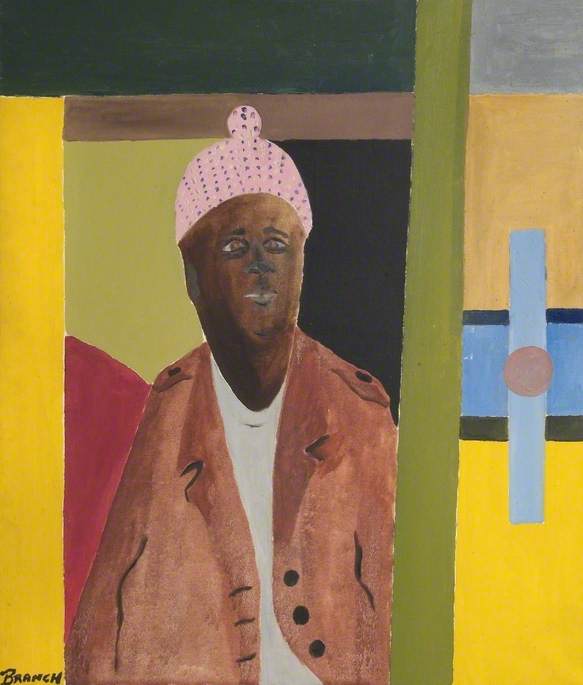

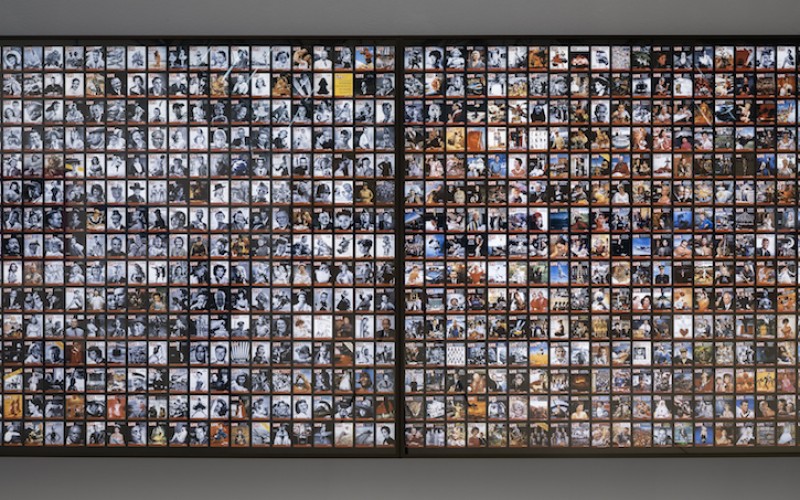

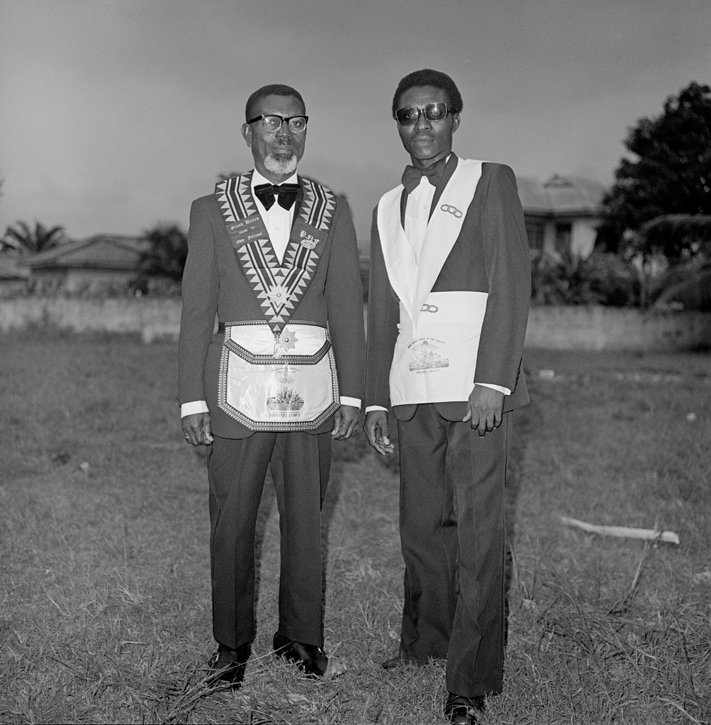

Odd Fellows Lodge

1975, photograph by James Barnor (b.1929)

On the topic of shooting in colour, Barnor tells me: 'When I was in Ghana I never once took a photograph in colour. Suddenly I found myself in London taking pictures in colour of Black women for the cover of magazines. It was insane.' He adds: 'It wasn't easy to access colour in Ghana – it was mainly Europeans or people with overseas connections who would shoot in colour. I didn't even realise at the time that it positioned me above the average Ghanian photographer.'

Visitor at Studio EX 23

1975, photograph by James Barnor (b.1929)

When asked how he feels about his late foray into the public eye, he says: 'I was 80 before my first real exhibition, which was at Harvard University's Du Bois Institute', he continues: 'When I was selected for my first solo exhibition, I thought – no not me. You can't possibly be talking about me.'

I went on to ask him if he at all felt resentful that his pioneering work had only come to the public's attention later in life; he asserts 'No, I'm lucky at 91 to be alive to see the recognition I have finally received. I had to go through difficult processes to get to where I am, and because of that, I've paved the way for other Black photographers to be recognised.'

Siham Ali, freelance writer

Follow James Barnor on Instagram to see more images from his archives