On 18th June 1817, the Prince Regent opened a new bridge over the Thames to celebrate the second anniversary of the Battle of Waterloo.

John Constable, then living in London, probably witnessed the festivities. He would spend the next fifteen years working on versions of the scene. The recently cleaned Anglesey Abbey painting now dazzles in its celebratory, sunlit naturalism.

The Embarkation of George IV from Whitehall: The Opening of Waterloo Bridge, 1817

John Constable (1776–1837)

A final version, The Opening of Waterloo Bridge ('Whitehall Stairs, June 18th, 1817'), was exhibited to mixed reviews at the Royal Academy in 1832. As the title makes clear, this is a double celebration: of a major new piece of engineering and of the famous victory over Napoleon.

The Opening of Waterloo Bridge ('Whitehall Stairs, June 18th, 1817')

exhibited 1832

John Constable (1776–1837)

Constable was deeply patriotic and his work evokes the popular enthusiasm widely reported at the time. Famous for his judicious use of red highlights, Constable here lavishes the colour throughout the canvas, with celebratory but also militaristic effect. The dramatic sky suggests the turbulence of war, now receding into memory.

Equally, his anachronistic inclusion of the Shot Tower, which was only built in 1826, strikes a martial note, standing like a pale sentinel on the right of the bridge. If Constable is channelling his patriotism, he is also doffing his cap to artistic tradition: the pageantry recalls Canaletto's Westminster Bridge, with the Lord Mayor's Procession on the Thames of 1747 found in the Yale Center for British Art.

Westminster Bridge, with the Lord Mayor's Procession on the Thames

1747

Canaletto (1697–1768)

Early nineteenth-century London was a major city – it had a population of 1.5 million in 1821 – but the realities of urbanisation are no more than a few wisps of smoke on Constable's horizon. The same is true of his contemporaries.

For Charles Deane, the Thames is a place of picturesque bustle. Commerce, travel and leisure mingle timelessly against an ever-serene sky and the mood is set by the parasol-ed ladies and elegant billows of sails, rather than the tumble of warehouses on the right.

Waterloo Bridge and the Lambeth Waterfront from Westminster Stairs, London

1821

Charles Deane (1794–1874)

Fredrick Nash uses the muddy foreshore on the left primarily as a pictorial contrast to the soft sunlight which warms the stone of the bridge and draws our eye into the distance as seen in the 1925 painting The Thames and Waterloo Bridge from Somerset House.

The Thames and Waterloo Bridge from Somerset House

c.1825

Frederick Nash (1782–1856)

J. M. W. Turner's unfinished oil of The Thames above Waterloo Bridge (c.1830–1835) is an exception to these idealised scenes, focussing instead on a steamer's puthering black smoke and the encroaching shadows of urban development in the foreground.

But Turner is as interested in meteorology as in modernity, and this, like Snow Storm – Steamboat off a Harbour's Mouth (1842) pits humanity, and its creations, against dynamically Romantic nature.

Snow Storm - Steam-Boat off a Harbour's Mouth

exhibited 1842

Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851)

By the 1860s, London had doubled in size: it was overcrowded, polluted and stinking, and that reality was increasingly difficult to ignore.

In The Thames from a Wharf at Waterloo Bridge (c.1866), Edwin Edwards, influenced by James Abbot McNeill Whistler's early realism, foregrounds the working river.

The dark angularity and heavy impasto of the cranes thrust towards the viewer are tactile, grimy and inescapable. There is no room for pleasure or colour on this river and the horizon is penned in with cheek-by-jowl houses and smoking chimneys.

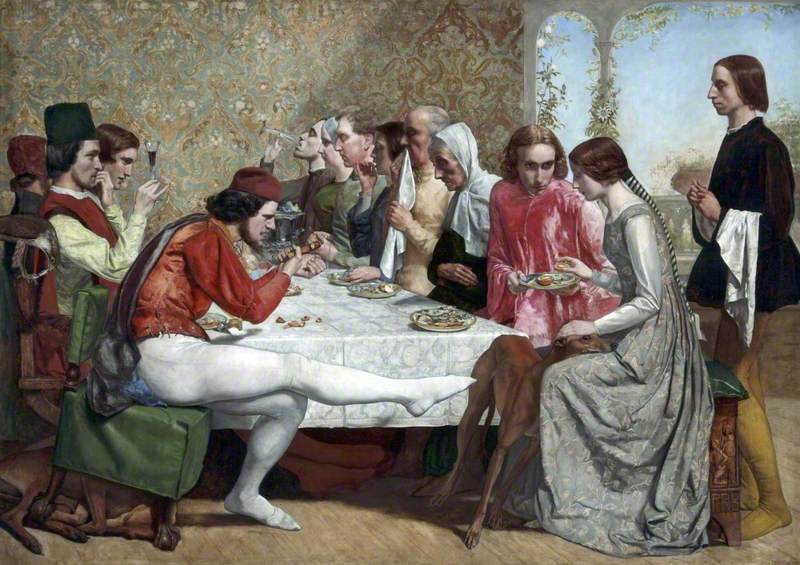

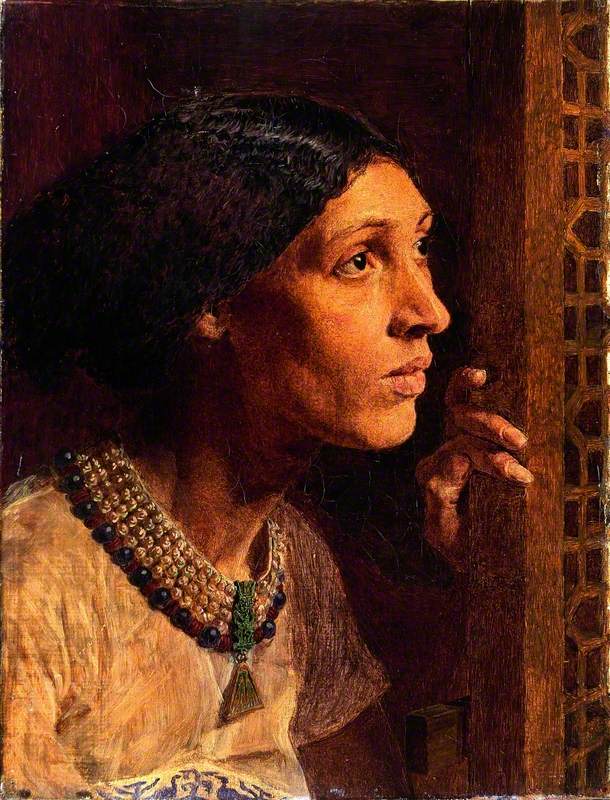

By now Waterloo Bridge was synonymous, not with military victory, but suicide. It was famously the setting for Thomas Hood's 1844 poem Bridge of Sighs, about the death of a 'fallen woman'. The tragedy, and its location, appealed to artists like John Everett Millais, and, perhaps most famously, George Frederick Watts.

In Found Drowned (1848–1850) he uses the architecture of the bridge to frame his victim with a timeless and almost religious solemnity. She is illuminated with an unearthly light, her arms forming a crucifix, a symbolic single star shining top centre. And the bridge acts to separate her from the shadowy city, and the world, which condemned her.

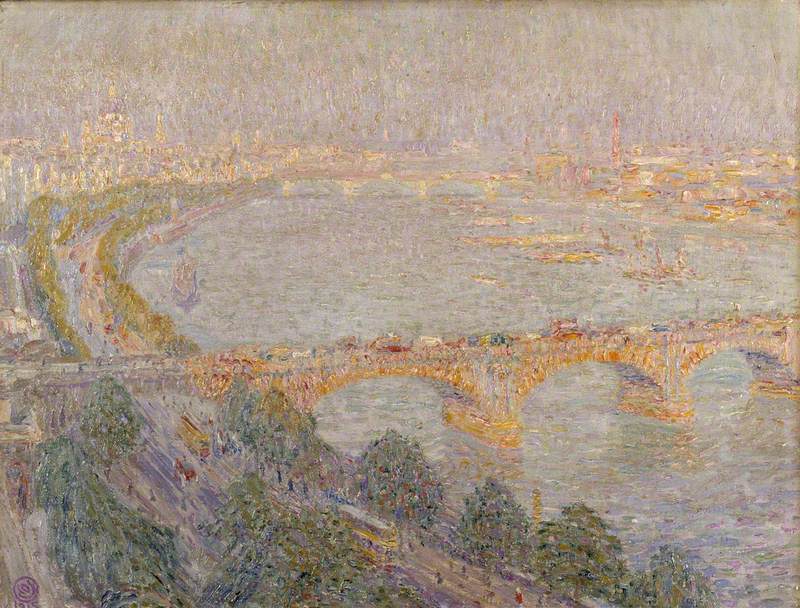

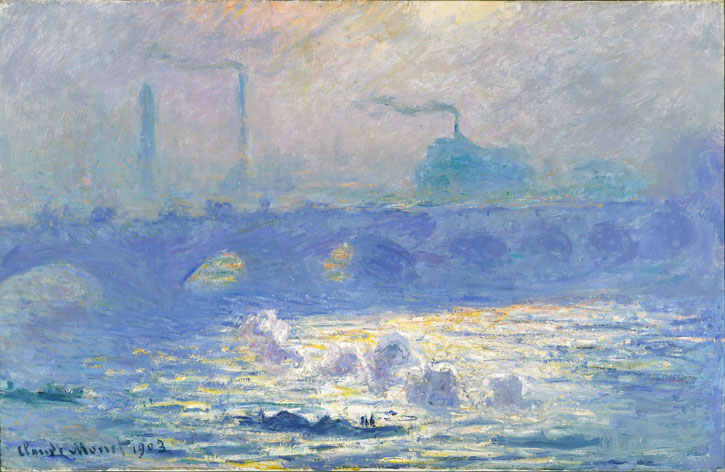

Perhaps the most famous images of Waterloo Bridge are Claude Monet's 41 canvases painted during visits to the Savoy Hotel from 1899: one of which is being auctioned this month.

Waterloo Bridge

1903, oil on canvas by Claude Monet (1840–1926)

Monet was fascinated by the effects of light dissipated through London's smoggy atmosphere, but he also effectively captured the teaming humanity and transient flux of modern life in the capital.

Waterloo Bridge, Grey Day (1903) shows the bridge is weighed down with people and vehicles; seeming, from Monet's higher viewpoint, almost to be sinking into the choppy waters of the Thames.

Waterloo Bridge, Gray Day

1903, oil on canvas by Claude Monet (1840–1926)

Yet for all the smoke and fog, the beauty of the city, and the artist's love for it, shine through in the vibrantly applied dashes of colour.

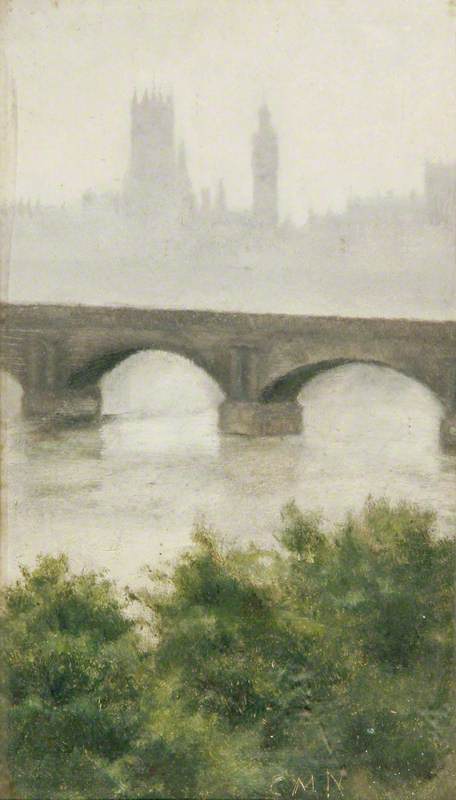

There's a similar enthusiasm in Christopher Nevinson's Blackfriars Bridge (c.1927) which looks across to Waterloo.

Blackfriars Bridge, London

c.1927

Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson (1889–1946)

The Impressionist-influenced composition creates a dynamic 'V' where figures hurry purposefully along almost silver streets, spilling out of the canvas. Lamps rear up like fern fronds in the foreground and trees waving along the waterline show this is a living, growing city for all its monochrome palette.

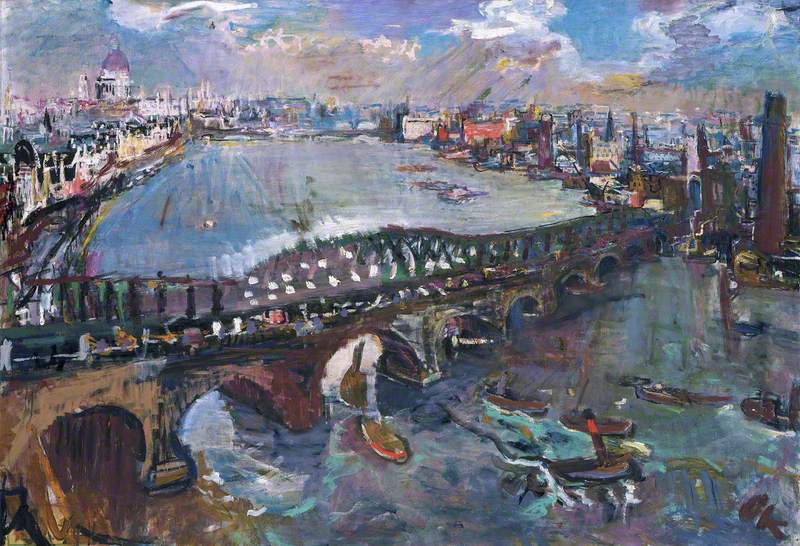

Waterloo Bridge, however, was coming to the end of its life. It suffered a partial collapse in 1924 and in Oskar Kokoschka's bird's eye view (1926), painted, like Monet's, from the Savoy Hotel, it seems a weary old thing, slumped across the river.

After ten years of debate, 'the noblest bridge in the world', as Antonio Canova once described it, was finally dismantled stone by stone.

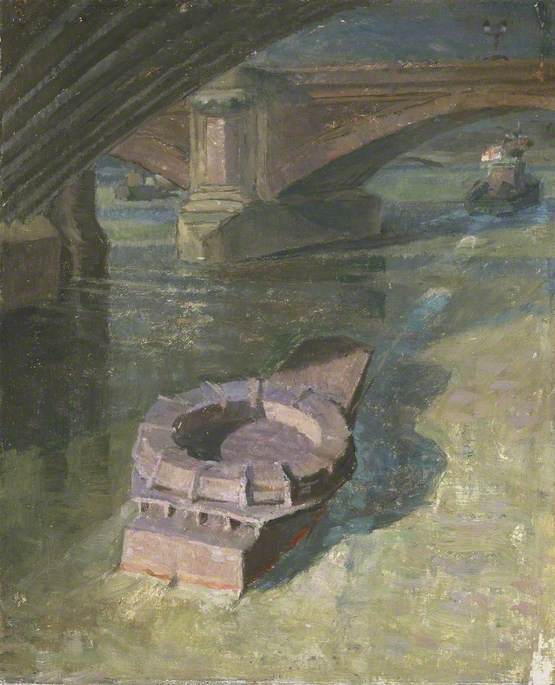

Charles Cundall elegiacally captured the demolition (1935), his low viewpoint showing cranes like siege engines attacking a castle, men swarming the ramparts and the girders of its temporary replacement growing like a parasite on its back.

In contrast, Nevinson recorded the functional, temporary structure (1938) with matter-of-fact, almost photographic precision.

The Temporary Waterloo Bridge, London

1938

Christopher Richard Wynne Nevinson (1889–1946)

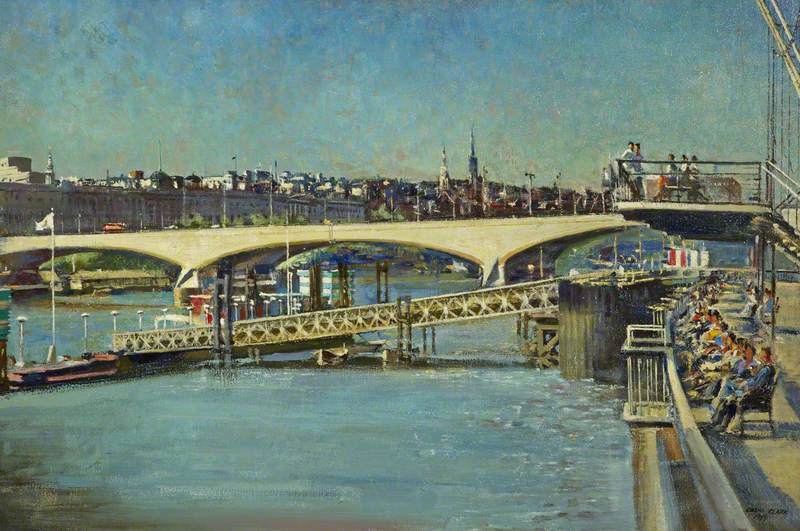

There were already plans for a grander design with Giles Gilbert Scott drafted in as architect and the new bridge opened without ceremony in 1942. It was nicknamed the 'Ladies Bridge' after its largely female workforce, but there was no official name change – Waterloo was a much-needed talisman in wartime. Scott's low arches had a streamlined modernity but remained rooted in architectural tradition.

Wartime Traffic on the River Thames: River Minesweepers

1942

John Edgar Platt (1886–1967)

In John Edgar Platt's Wartime Traffic on the River Thames (1942) they swoop protectively over the rescue attempt, channelling angled sunlight to illuminate a small act of humanity in the midst of war.

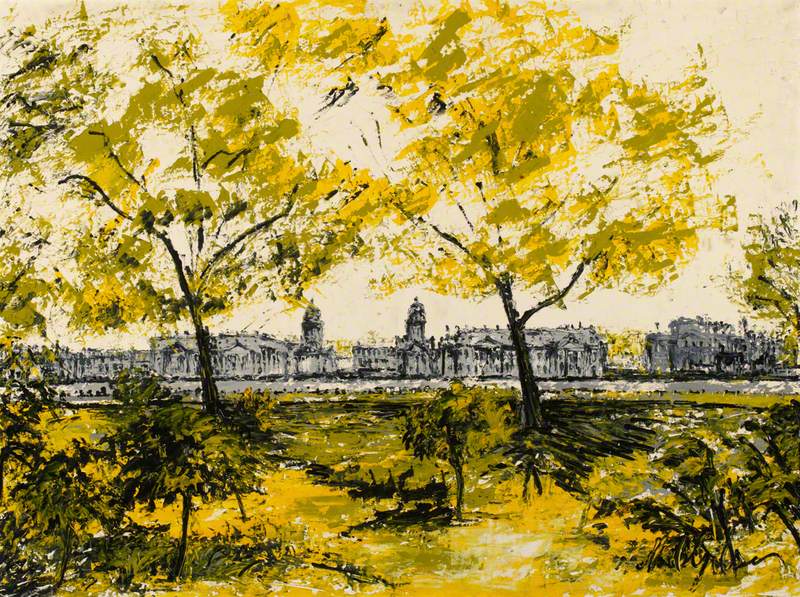

In a sense, the story comes full circle. Cundall's 1943 view looks back to Constable and Canaletto.

Waterloo Bridge strides across the canvas, watched over by St Pauls, under a clear blue sky. And in 1951, as crowds crossed it to visit the Festival of Britain, the bridge was once more the focus of optimistic post-war patriotism.

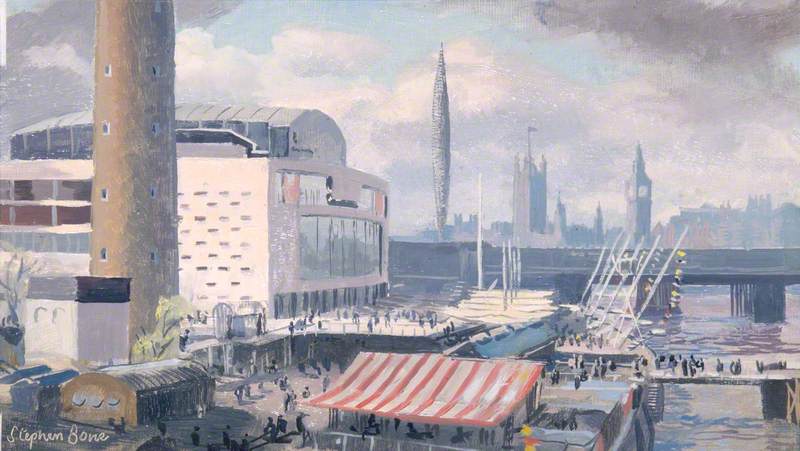

The Shot Tower, first seen in Constable's painting and now repurposed as a radio beacon, is a solid presence in the foreground of Stephen Bone's view from the bridge (1951), a nod to the past as the Skylon shoots up with futuristic dynamism in the centre.

It features again in Frederick Gore's Coronation Fireworks (1953).

Confident expressionist brushstrokes create an exuberant plume of colour which is reflected in the water under the arches of the bridge. The battle of Waterloo had receded from popular memory but Waterloo Bridge was once again the centre of celebration.

Catriona Miller, art historian and freelance writer