The exhibition 'Feast & Fast: The Art of Food in Europe, 1500–1800' at The Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge (26th November 2019 – 26th April 2020) reinforces the notion that 'we are what we eat'. Our religions, culture and even our national identity are defined by what foods we consume.

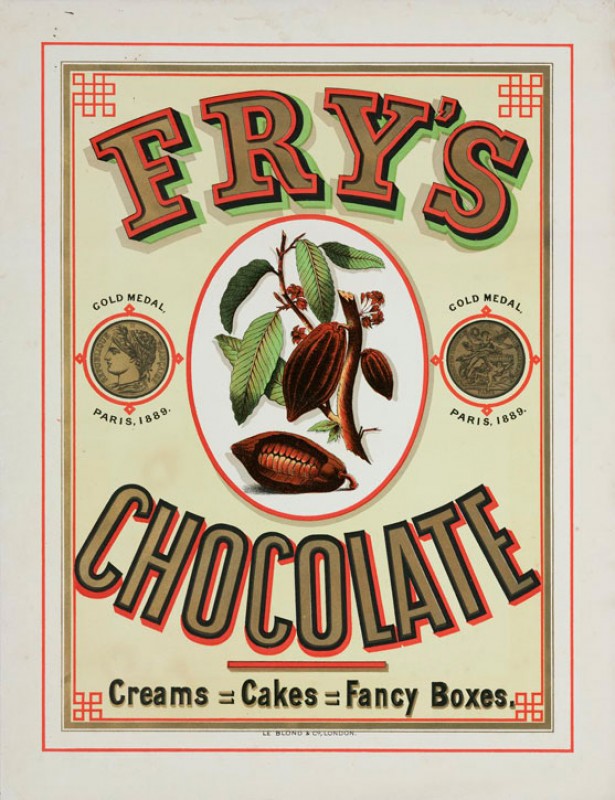

Food is more than a form of survival and nourishment. It also symbolises traditions, entrenched attitudes and even geopolitics. For example, Europe's insatiable appetite for sugar, coffee and tea from the sixteenth century onwards was one of the driving forces behind the expansion of colonies and empire.

Famine and the scarcity of grain in France in the 1770s was one factor among many that led to the French Revolution, further sparked by (almost certainly false) allegations that Marie Antoinette had proclaimed: 'Let them eat cake!'

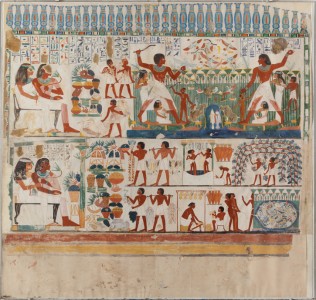

As we enter the festive season of Christmas, there is perhaps no better time to talk about food and feasting – a cultural activity that has been a popular subject in art history since at least the ancient Romans, who are today particularly notorious for their gluttonous eating habits.

Let's delve into an alternative art history, to explore how food culture has permeated our culture.

Bacchanalian feasts

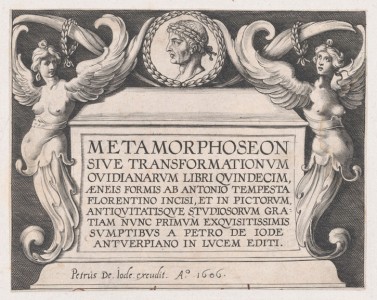

In Greek mythology, Dionysus was the god of the grape harvest, wine, pleasure and fertility who was later adopted by the Romans as the god Bacchus.

An embodiment of hedonism, inebriation and bodily abandon, Dionysus and Bacchus were typically portrayed at a drunken banquet, dining and boozing it up among the satyrs, maenads and bacchantes.

Apart from wine, Bacchus was also the god of agriculture and is usually depicted next to vines and grapes.

Biblical feasting

In the Jewish Torah and Christian Old Testament, stories were sometimes presented in the setting of banquets and feasts, like the story of Belshazzar's Feast, probably most famously depicted by the Dutch master Rembrandt van Rijn.

The story is to be found in the Book of Daniel. The Babylonian king, Belshazzar, hosts a grand feast for his lords. There, he commands that the vessels from the destroyed Temple in Jerusalem be brought in so that they can drink. At the same time, a hand appears and writes on the wall – a text which proclaims the end of Belshazzar's days as ruler. (Hence the phrase 'the writing's on the wall'...)

Moving into the New Testament, a popular artistic subject matter was the feast of Herod, showing the moment when Herodias' daughter, Salome, presents the decapitated head of John the Baptist on a silver platter.

This version was painted by Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) in the mid-seventeenth century.

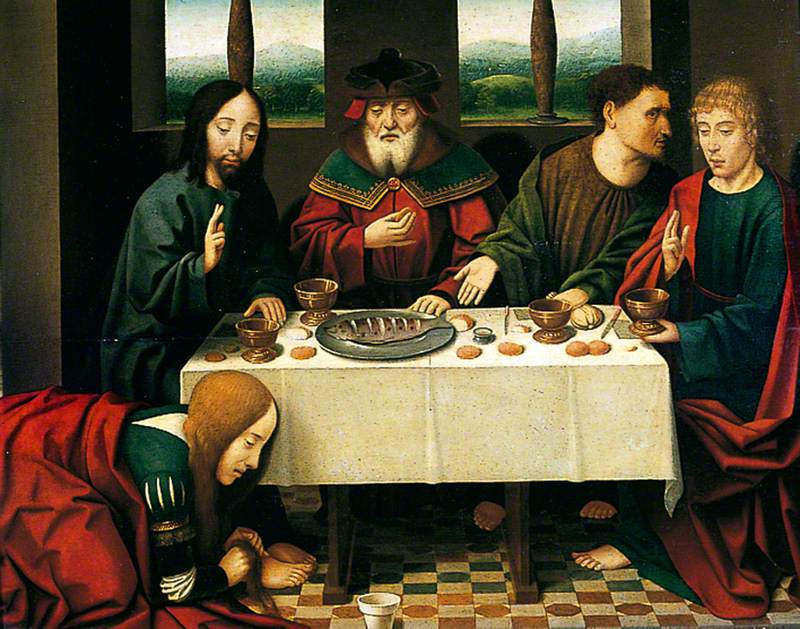

Jesus has often been presented feasting or sharing food with his disciples and followers.

From parables such as Christ's feeding of the five thousand to the story of the Last Supper, Biblical narratives have used food to demonstrate Christ's ability to perform miracles.

The gesture of Jesus sharing food has served as a powerful metaphor for the spreading of the Christian faith. Christ was often embodied through the symbols of fish, bread and wine.

In this Flemish School painting, Christ is depicted in the house of Simon the Pharisee. Fish and bread adorn the table, reminding us of the story of Christ feeding the five thousand. Simon had invited Jesus to his house and is hosting a meal for him. During the banquet, a sinful woman kneels before Jesus's feet begging for redemption, which Christ grants her – to Simon's astonishment.

The Last Supper

(copy after Leonardo da Vinci) c.1520

Giampietrino (active 1500–1550)

The most famous Christian tradition of representing feasting and food is the Last Supper, a subject matter which is probably most famously depicted by Leonardo da Vinci, who first began painting his fresco version in 1495 in the refectory of the Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan. Many versions have copied Leonardo's – either just in composition, or directly, as in this cast iron relief.

One of the most recognisable subjects in art history, the Last Supper marks the moment before Christ's arrest when he tells his followers that one of his disciples will betray him. At this meal, Christ instructed the disciples to eat and drink in remembrance of him, thus establishing the basis of the Eucharist – the Christian sacrament of eating the wafer and drinking wine at Holy Communion, symbolising the body and blood of Jesus.

Caravaggio's 1601 painting The Supper at Emmaus shows the scene where the resurrected Jesus appears before two of his disciples on the road to Emmaus.

Food is highly symbolic in this painting. The scallop shell worn by Cleopas (the man gesticulating on the right) signifies that he is a pilgrim.

On the table lies a basket of fruit, fowl and bread. The fowl on the plate mirrors Christ's recent death, while the bread represents the body of Christ.

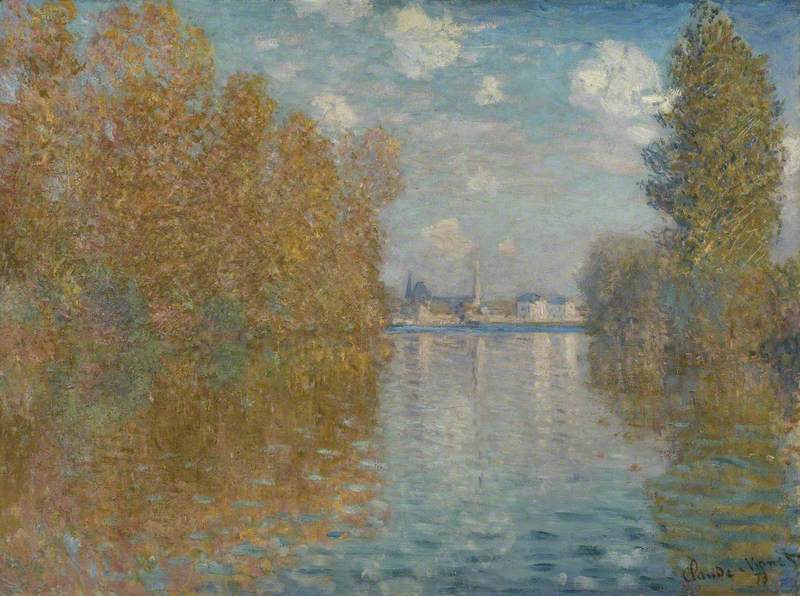

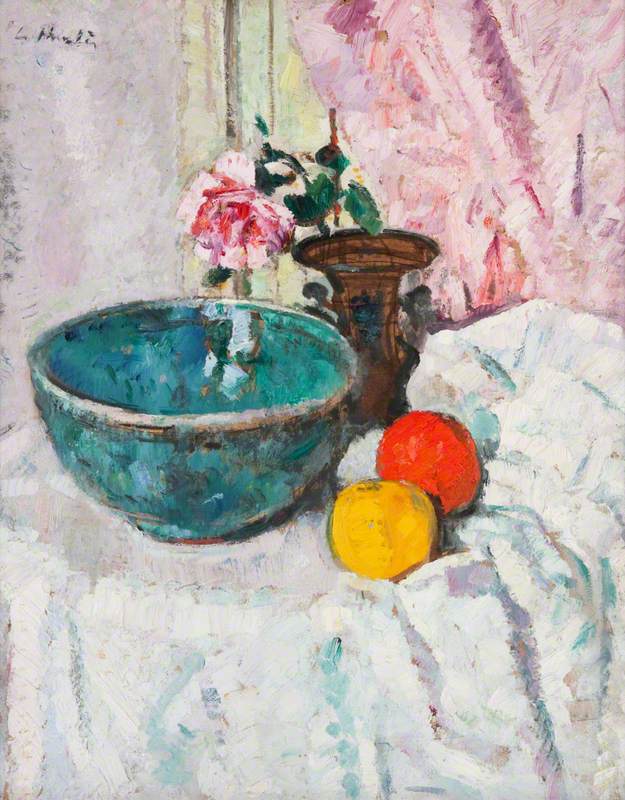

Baroque and Dutch still lifes

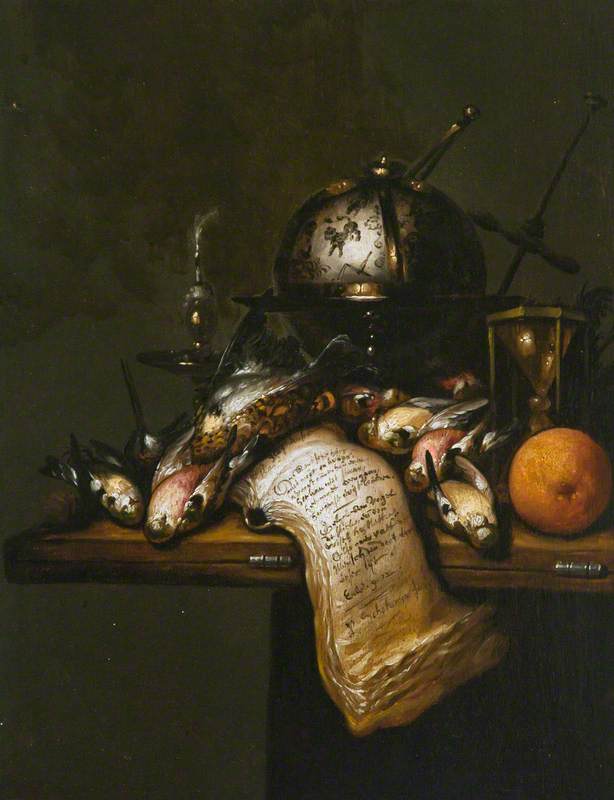

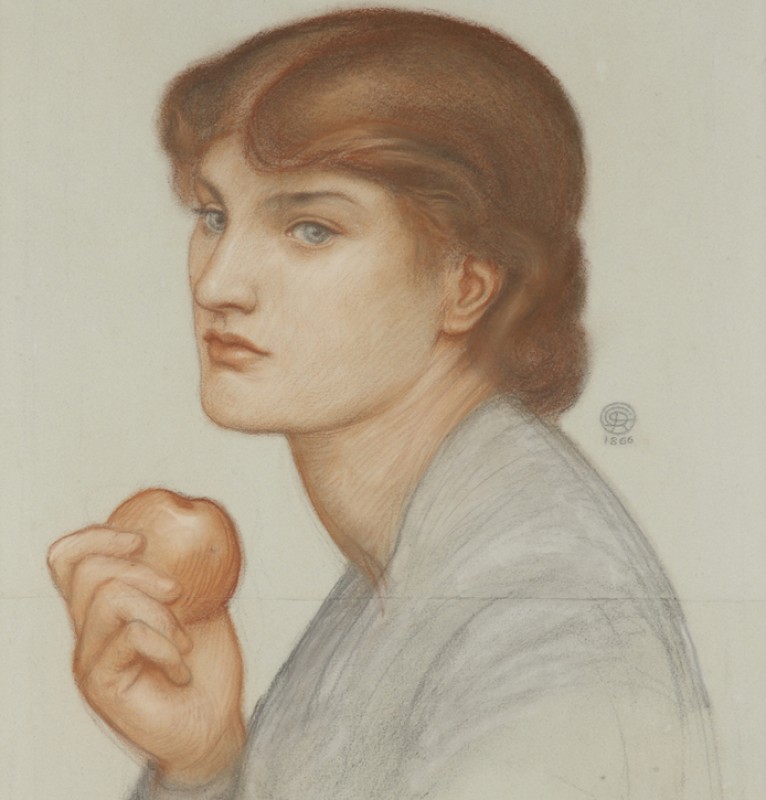

The seventeenth century reinvigorated the tradition of the still life and banquet scene, in which a proliferation of rotting fruit would be painted next to blooming or withered flowers or other objects symbolising memento mori (a reminder that life is transient and we will die).

The painterly genre known as 'vanitas' intended to remind viewers of the mortality and often featured food – to show that even worldly pleasures perish over time.

But the tradition of showing exotic foods in still lifes was also due to expanding overseas trading and colonisation of the West and East Indies, Africa and Asia. In particular, the Netherlands reaped much of its national wealth from importing foreign fruits, spices and precious gems to its Dutch ports.

Still Life of Food, a Jug and Glasses on a Table

1640

Pieter Claesz. (1597/1598–1660)

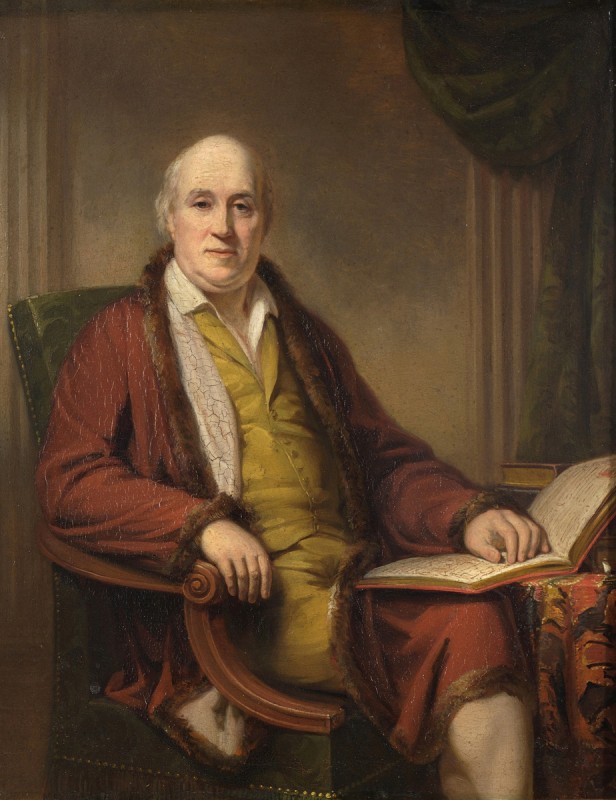

The burgeoning genre of the still life in seventeenth-century Holland was a reflection of such colonial trading made by the Dutch East India Trading Company. By the seventeenth century, cities like Antwerp and Amsterdam were the epicentre of the mercantile world, where the middle classes prospered and became patrons of the arts.

For similar reasons, the pineapple became a status symbol in Europe after Christopher Columbus returned from South America and the New World. An expensive, rare and exotic item, pineapples became a sought-after fruit, especially in the eighteenth century.

You can read more about the colonial roots of the pineapple and its ubiquitous presence in art history in our story about 'pineapple mania'.

Still Life of Fruit and Flowers with Bird's Nest on a Marble Ledge

Jan van Os (1744–1808)

In the early seventeenth century a leading female Dutch painter, Clara Peeters (c.1585–c.1655), was known for introducing the 'breakfast piece' (or ontbitjes) to the genre of Dutch still life. In these paintings, Peeters would paint all of the ingredients of a simple meal, often presenting food types that symbolised the Dutch identity, such as bread, butter and cheese.

Still Life with Shellfish and Eggs

c.1590–1630

Clara Peeters (c.1585–c.1655) (attributed to)

Other artists of the same era, such as Joris van Son, painted expensive shellfish and crustaceans into their paintings – lobsters, crabs and oysters – all of which are imbued with different meaning and symbolism.

While the lobster and crab symbolised extravagance, the oyster was known for being an aphrodisiac or sexual innuendo.

The presence of sugar can also be found in European paintings from the sixteenth century onwards. In works such as this one, a bowl of sumptuous strawberries sits next to a sugarloaf and small box of sugar. The rise of sugar was again linked to the expansion of Europe's colonies. Throughout the seventeenth century, the number of sugar refineries in Amsterdam multiplied rapidly in an attempt to meet the demand of middle-class consumers.

Christmas

In the modern era, feasting has become synonymous with Christmas – the annual festive tradition that often results in excessive eating and drinking.

As you prepare your Christmas meal this year, remember that your food is laden with art historical symbolism.

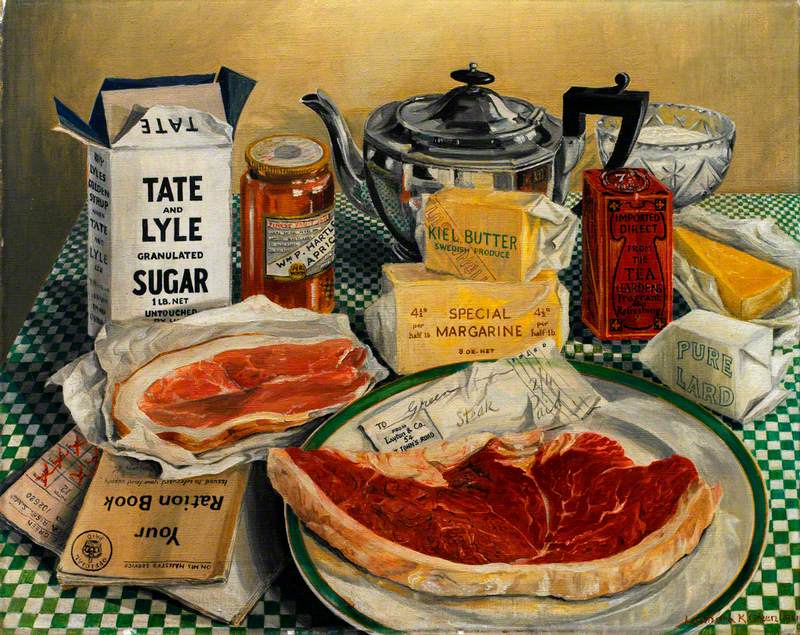

Still Life at Christmas

1953–1954

Michael Ayrton (1921–1975)

And if you're fortunate enough to be continuing this tradition, be thankful for the bountiful feast – eat, drink and be merry!

Lydia Figes, Content Creator at Art UK

'Feast & Fast: The Art of Food in Europe, 1500–1800' is at The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, 26th November 2019 – 26th April 2020