Across five decades, Saleem Arif Quadri (b.1949) has been making work that draws on the natural world and which explores the idea of spiritual journeys. His initial training as a sculptor is clear in his artistic practice more broadly, which often plays with spatial fragmentation to meditate on absence and presence. In fact, he has consistently returned to the idea of 'pregnant space', suggesting meaning is found in the gaps.

Born in Hyderabad, India, Quadri emigrated to Britain with his family in the 1960s when he was 17. He studied at Birmingham School of Art and then the Royal College of Art, London. After he graduated in 1975, he returned to India as a visitor, later travelling widely in North Africa, Europe and Asia. Much of his work reveals Eastern and Western influences.

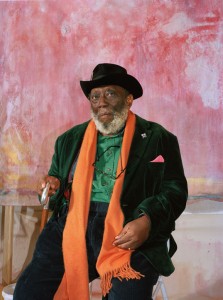

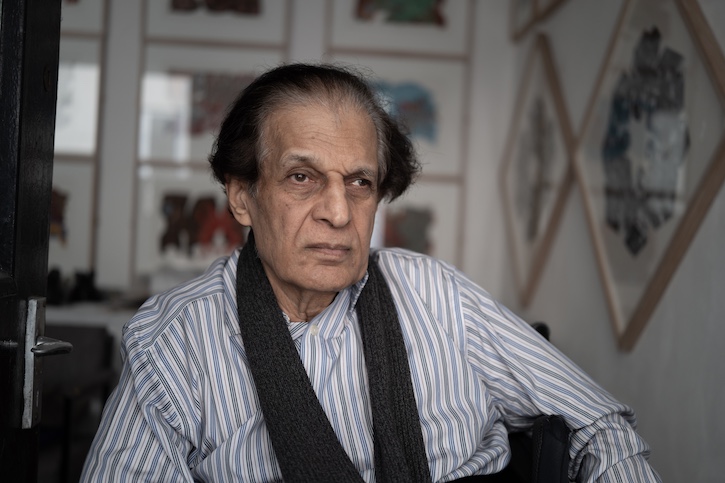

Saleem Arif Quadri in his London studio, February 2025

I first met Quadri in 2022 at a talk on Islam and modernism, and our conversations since have led to a deeper understanding of his work. This text is the result of one of those discussions, and it touches on what negative space, or the space in between, means to him – a space that meditates on faith, heritage and abstraction.

Like many artists whose experiences and practices navigate between the canonised narratives of British art history and more pioneering ones, Quadri's story is often fragmented, mirroring the reception of both the artist and his works. His presence in numerous public collections, while significant, is not always framed in the context of his wider artistic journey. I want to highlight Quadri's evolving practice – he is still working in London – in order to make clear the themes and interests that have consistently guided his practice.

Hassan Vawda and Saleem Arif Quadri in Quadri's London studio, February 2025

When asked about his formative inspirations, he tells me about how his desire to create came from his parents: his father, a surgeon, had a passion for the arts while his mother's quiet creativity, weaving and painting intricate designs on vinyl records, existed alongside maintaining the home and bringing up her children. 'The values of work, prayer, and respect for others were ingrained in me,' he says. Though his decision to pursue art initially met resistance, it was ultimately embraced by his family, offering him the encouragement to develop his practice.

Quadri makes clear the importance of his early childhood in India. 'My early childhood experiences in India played a crucial role in exposing my intuitive mind to the wonders of nature,' he tells me. 'Sleeping in the open alongside my family in those extremely hot nights, which was the custom during summer months, was a revelation to me. The sky became an "open roof", the magical movements of the stars in the dark sky enlightened my young mind.'

He clearly paints a vivid picture of the awe instilled in him at a young age by looking above to infinite space. 'Where did all this mysterious movement come from? Where was it going? Will it be with us the next night?' He recalls his parents 'quietly but firmly' responding to his questions by putting faith in the 'almighty maker'. This early memory of the infinite unknown, of finding confidence in the power of heaven and earth, has informed his life and artistic practice. Quadri notes that his art school education brought a different focus and direction, but that his artistic outlook remains tied to those formative impressions.

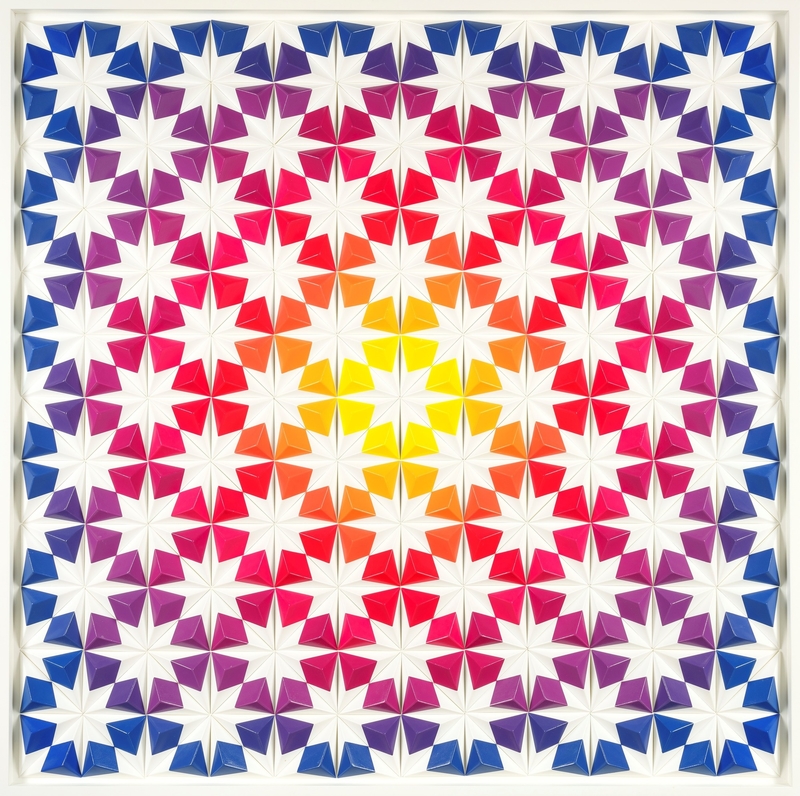

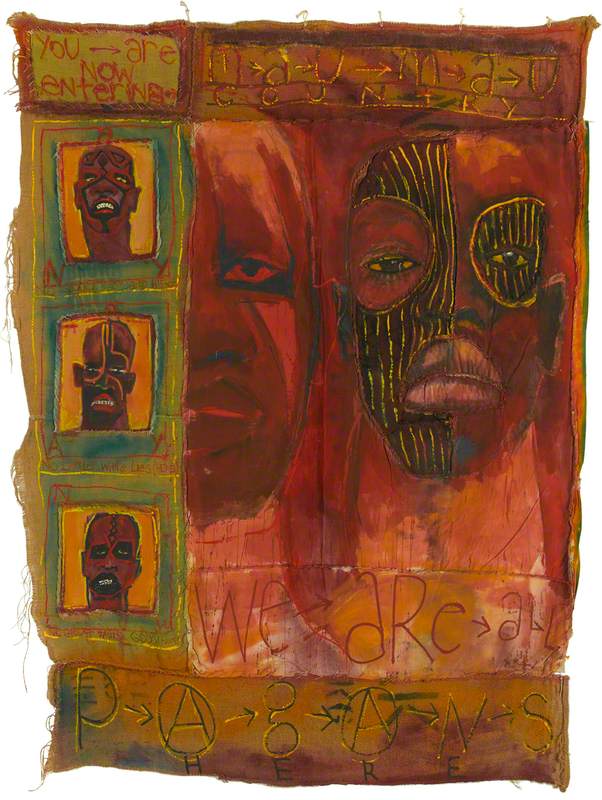

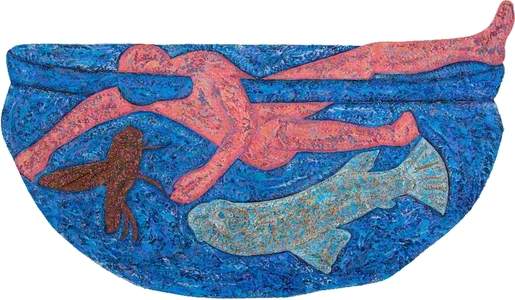

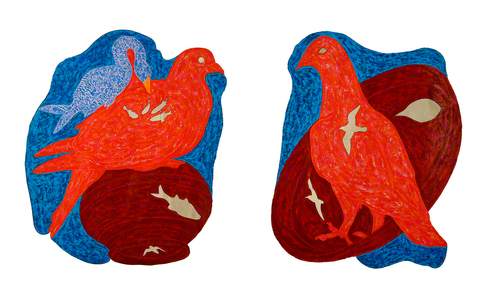

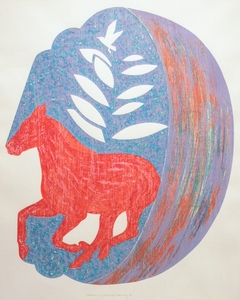

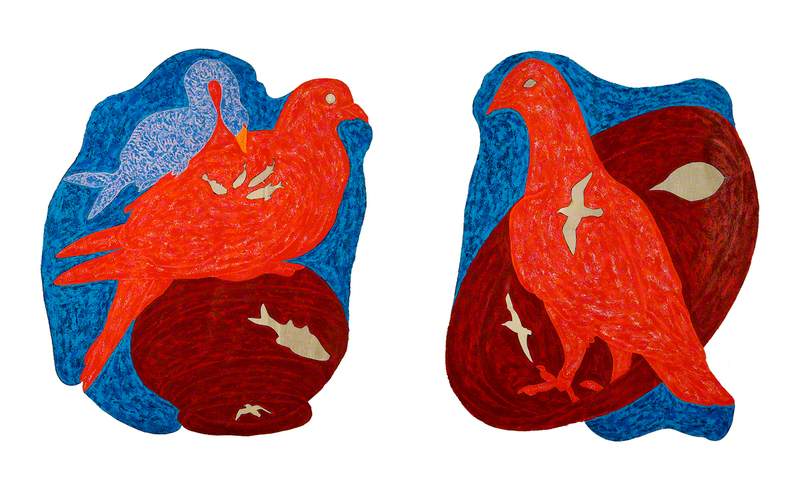

Pressed Against Good and Evil

1987–1988

Saleem Arif Quadri (b.1949)

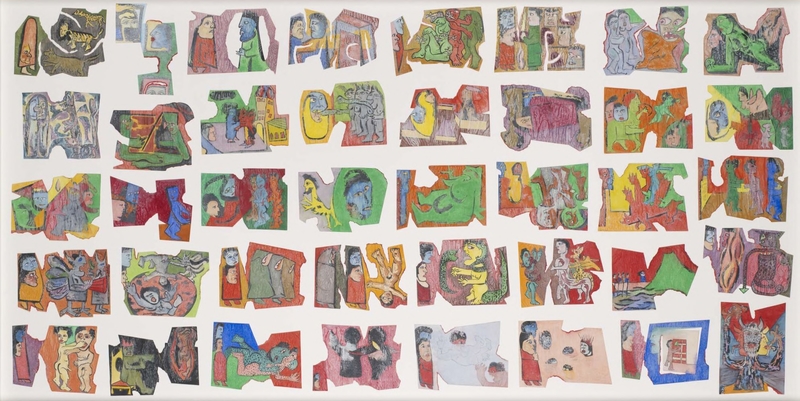

In 1978, his seminal work Dante's Inferno (1976–1977) was acquired by the Government Art Collection – his first to enter a UK public collection. Quadri became interested in Dante's epic poem Inferno (the first part of the Divine Comedy) while at the Royal College; by 1981, he had produced hundreds of small-scale works on paper. Quadri speaks with a quiet intensity about this period of exploration, driven by a fascination with history, folktales, philosophy, and religion.

'At this stage of my career, exploring a variety of disciplines was my main concern. My knowledge of Miraj/Isra was there since childhood, but not with a deep appreciation or understanding,' he tells me. He is referring to al-’Isrā’ wal-Miʿrāj, known in English as 'The Night Journey' – a significant moment in Islamic history, cosmology and belief, in which the Prophet Muhammad had a physical and spiritual ascension.

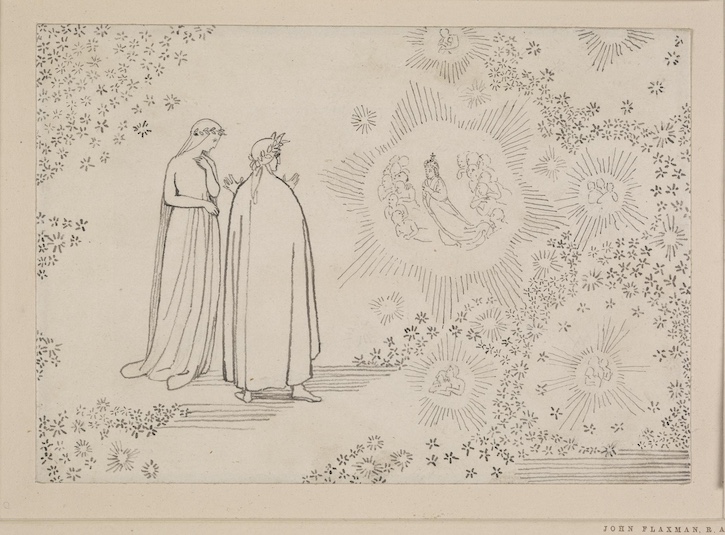

While researching at the Royal College of Art's library, a pivotal encounter with British sculptor John Flaxman's (1755–1826) drawings of Dante's Divine Comedy brought a spark of aligned curiosity.

'The similarities, the ideology – this was so reminiscent of my own religion taught in my youth,' he says. Later, his travels through India and Pakistan introduced him to Islamic scholar Miguel Asín Palacios' study Islam and the Divine Comedy, which argued that Islamic traditions shaped Dante's masterpiece. Quadri describes it as 'a magnificent work by a fourteenth-century Italian genius whose writing was not alien to me'.

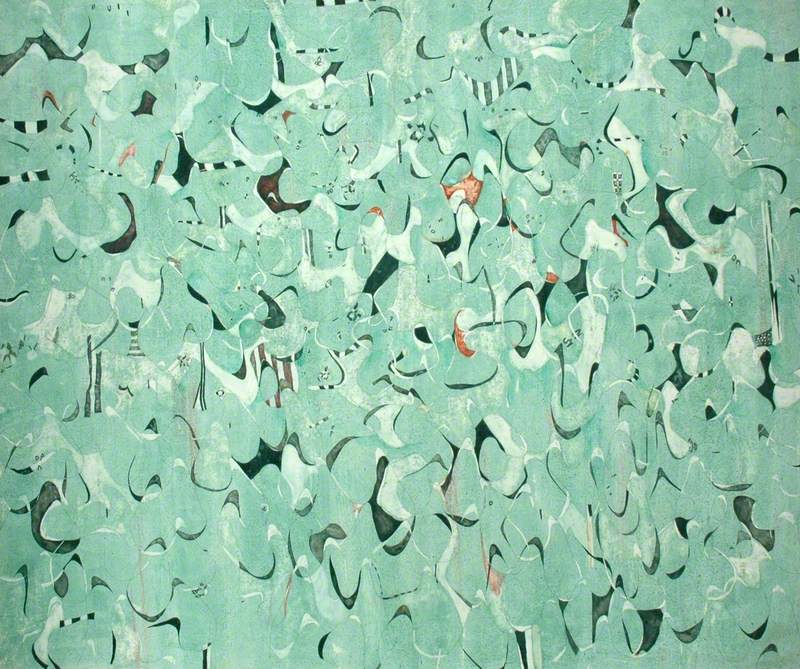

Dante's The Divine Comedy, Inferno Canto XXI 'Barrators in Boiling Pitch'

1976–1977

Saleem Arif Quadri (b.1949)

Inspired, Quadri began producing a series of brush and ink works that bridged these cultural connections. 'It became a foundation for my research. When I returned to London, I proceeded to do more research in several libraries,' he explains. Quadri's reflections illuminate how Dante's cosmology and the Islamic narrative of the Prophet Muhammad's ascension served as a profound meeting point of faiths and philosophies. In his work, these influences are not merely intellectual but also visceral.

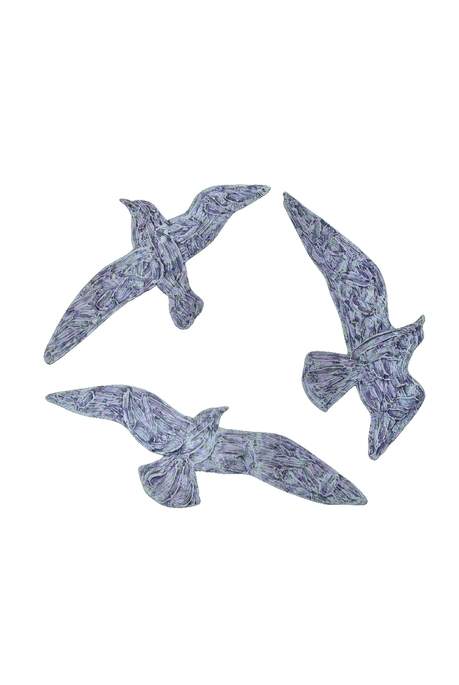

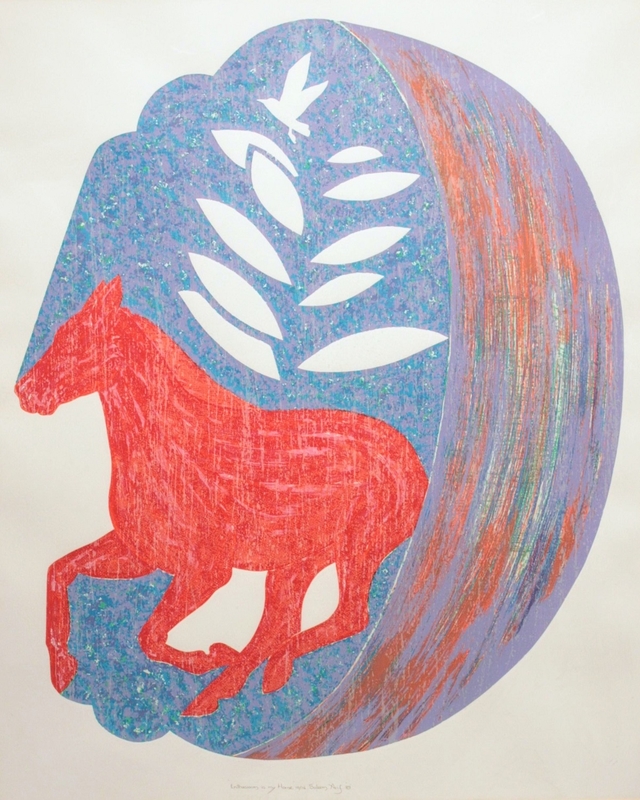

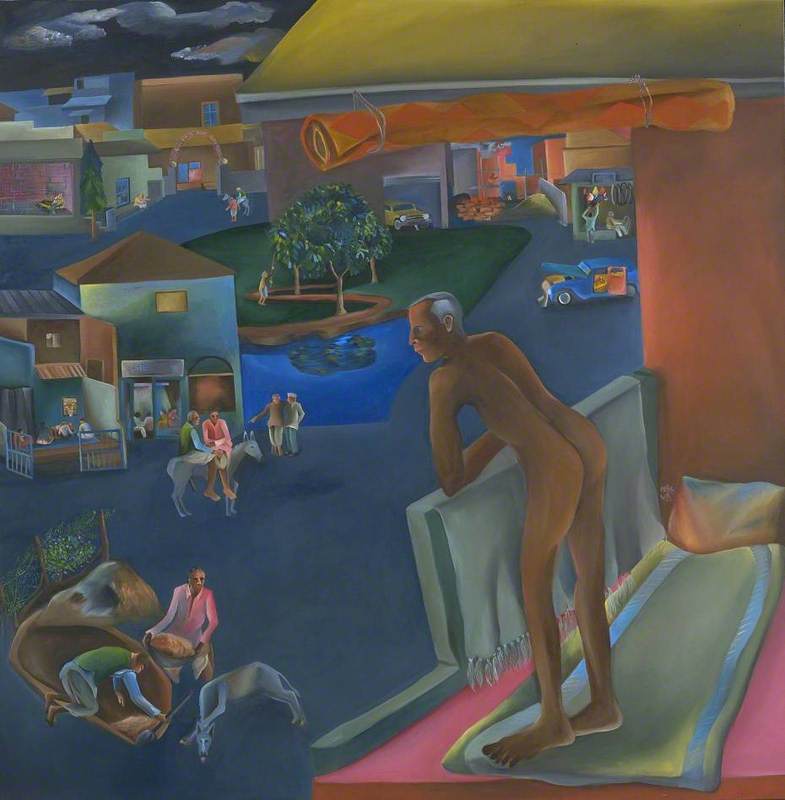

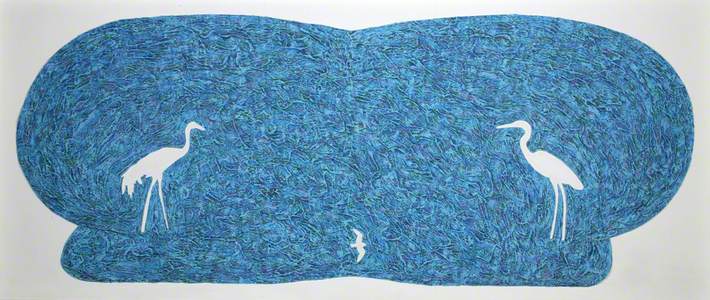

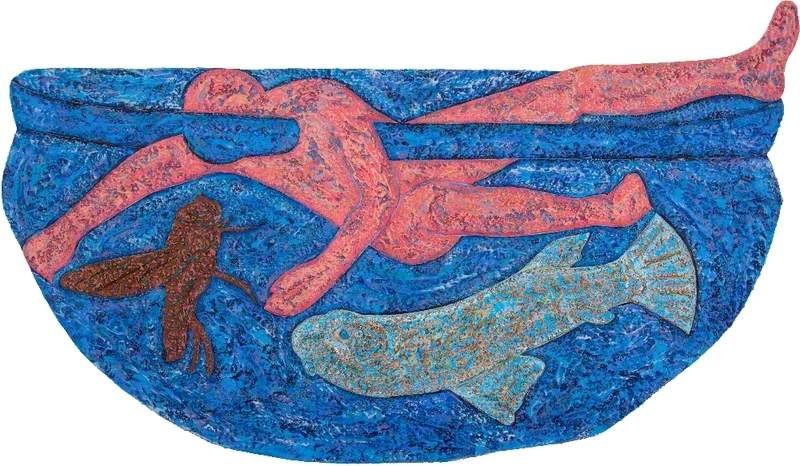

The 1986 work Harbour of Intimacy entered the Ipswich Museum's collection in the same year, following Quadri's solo show titled 'Garden of Expression' at Ipswich Art Gallery. This large-scale work – from the early 1980s his work grew in size as he considered new concepts and shapes – gives some sense of Quadri's increasing use of empty space during the 1980s.

He explains his focus on the natural world at this time, particularly the inspiration he drew from observing birds in flight and courtship: 'My attention turned to the behaviour of creatures in the animal kingdom, with particular reference to birds – how they fly in majestic form and, during mating, how the male seeks the female's attention,' he says. 'This phenomenon mirrors human interaction.'

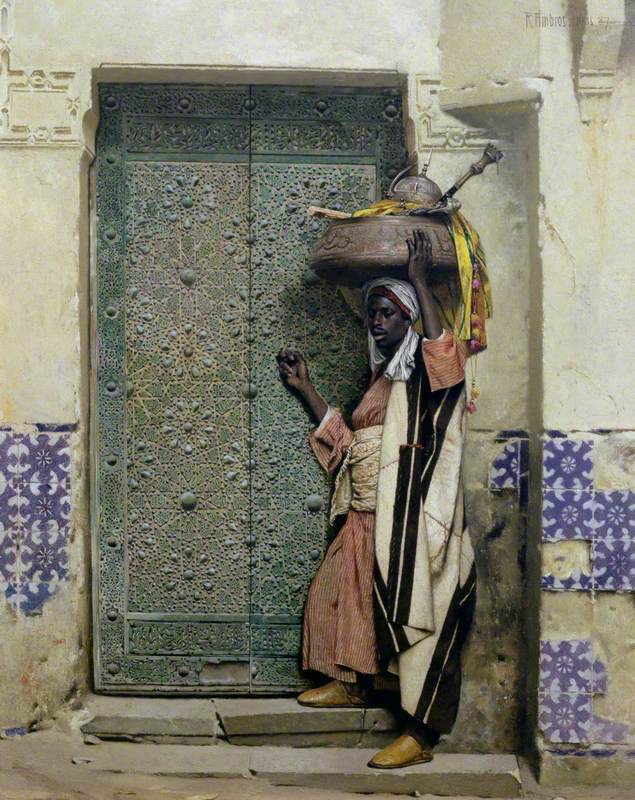

Harbour of Intimacy

(diptych) 1986

Saleem Arif Quadri (b.1949)

In this diptych, Quadri explores how absence can be as powerful as presence. 'My work with birds and fish in these "cut-out" images appears negative to the naked eye because of the space, but to me, they are positive spaces – specific images that subtly extend to the human presence,' he explains. 'I began to question the concept of negative/positive visual space,' he goes on. The spatial openings in works such as Harbour of Intimacy and Carpet of Contemplation become meditations on connection, patience, and shared experience.

During the 1980s, Quadri exhibited widely, including a display of his Dante works in 1983 at the Midland Group, Nottingham, and in 'From Two Worlds' at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1986. In 1989, he featured in the seminal exhibition 'The Other Story' at the Hayward Gallery, curated by Rasheed Araeen and which brought together the work of overlooked Asian, African and Caribbean artists in a post-war context.

Quadri was awarded an MBE for services to arts in 2008 – the same year that Magdalene Odundo and Frank Bowling were made OBEs – reflecting one of the ways in which the work of diasporic artists has since been formally recognised.

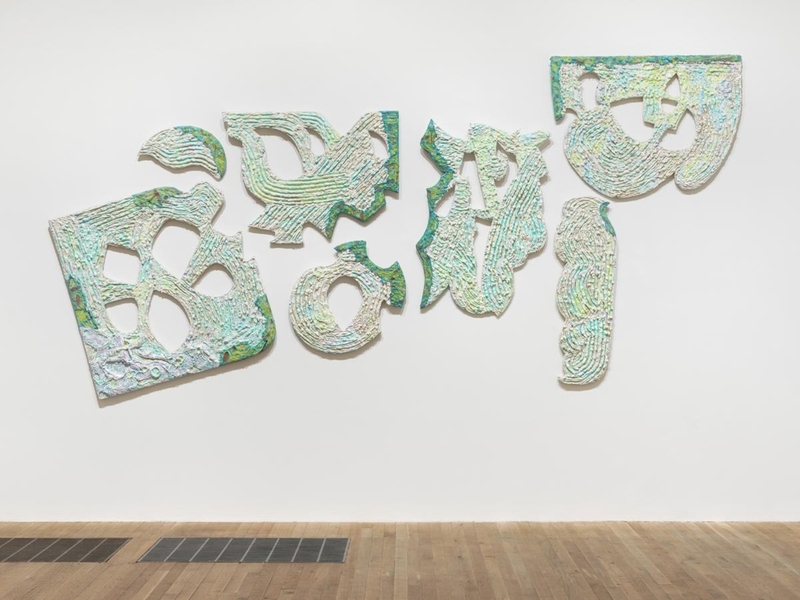

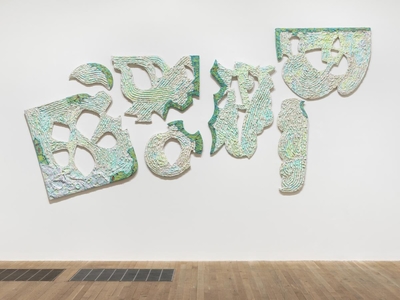

I describe to Quadri my experience of seeing Landscape of Longing (1997–1999) for the first time at Tate Modern, which is still on show as part of a display called 'Infinite Geometry', curated by Nabila Abdel Nabi, which considers artists working within the language of geometric abstraction. His interest in geometric forms dates back to his early sculptural piece Space Lattice, which won him 'Young Sculptor of the Year' in 1971.

Quadri suggests that Landscape is deeply personal, born from his journey to find stability and belonging. 'This work was inspired by the joy of securing my studio in London,' he tells me, describing it as a 'haven' that became a reality through perseverance as an artist and faith from his parents.

The piece, which features seven abstract cut-outs mounted to a wall, intertwines multiple elements: an oil lamp symbolising, as he describes it, 'the light of hope and humility', a descending flame, and subtle figures embedded within layered textures. 'The central image – a partial female figure – and a flower symbolising a garden emerged through experimenting with materials such as acrylic, sand, and oil,' Quadri says.

The work's layered process mirrors Quadri's eventual emotional and physical rootedness. 'At first, I had no title, no direction,' he admits, but as his life stabilised, the work revealed itself as a testament to longing and fulfilment.

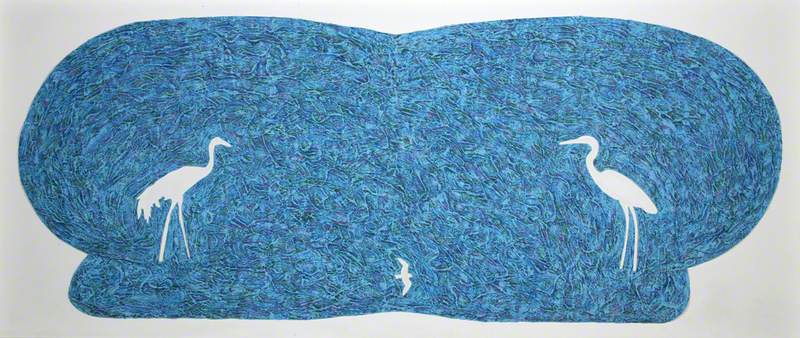

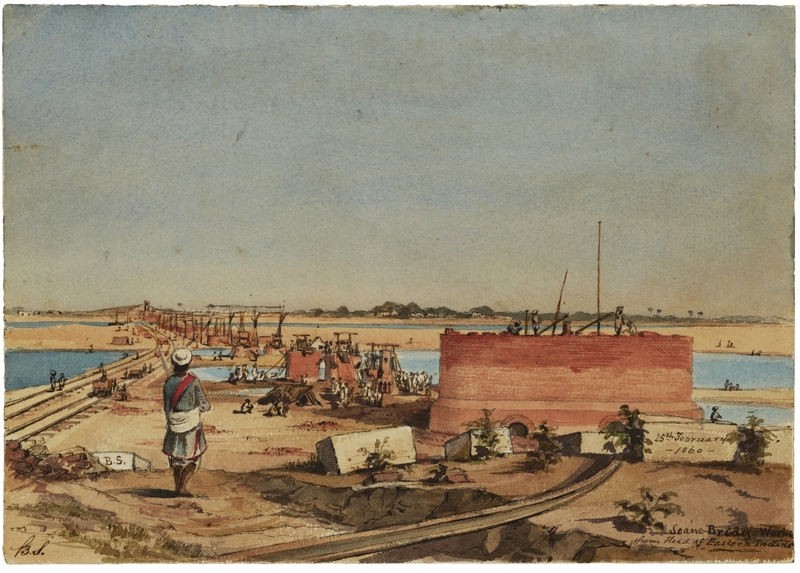

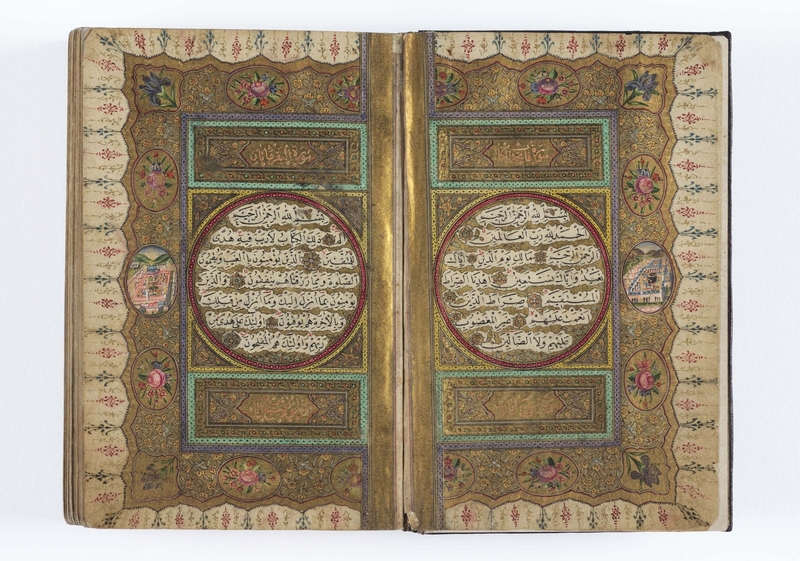

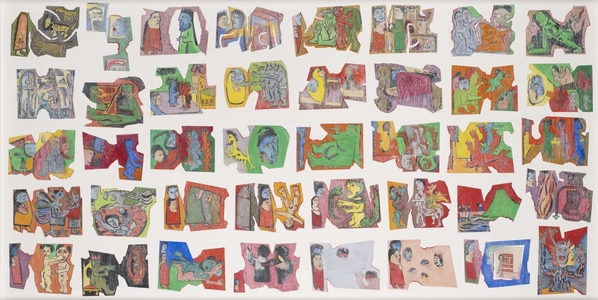

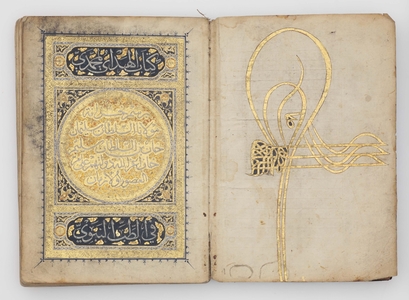

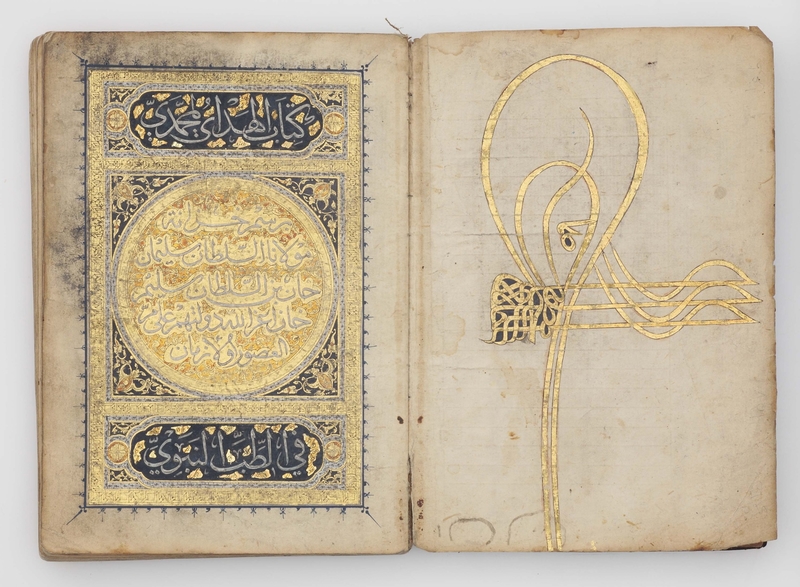

Whilst being an extension of his practice for some time, in recent years Quadri has drawn on the history of Islamic manuscripts, such as the one below, creating 'books without boundaries' as he describes them – works that exist somewhere between sculpture, paintings and manuscripts. They are collages of religious scriptural forms and abstract paintings which play with the expected format of books.

An example of Saleem Arif Quadri's illustrated books

Kitab al-Hadi al-Muhammadi fi'l-Tibb al-Nabawi (A Treatise on Prophetic Medicine)

926 AH (1520)

unknown artist

This is the latest artistic experiment in a lifetime spent gazing into the skies above and having confidence in an almighty power that brings balance. Quadri's creative journey is ongoing but still deeply tied to the teachings and resilience of his early life – his is a practice firmly rooted in faith and heritage.

Hassan Vawda, Doctoral Researcher at Goldsmiths/Tate

For more information, visit www.saleemquadri.co.uk

This content was supported by Jerwood Foundation