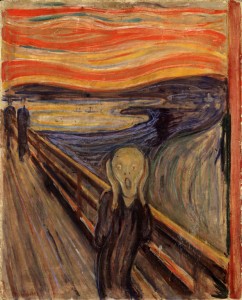

It is not just the nude body that is exposed in Ernst Ludwig Kirchner's (1880–1938) paintings. The scenery, too, is stripped back and nature itself is reduced to its rawest forms. Formally and stylistically, Kirchner championed a spirit of crude nature. His interest in woodcuts is largely rooted in their bare, angular linearity. Nature was both a theme in Kirchner's paintings, and the thematic underpinning of his artistic ideals.

Image credit: British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

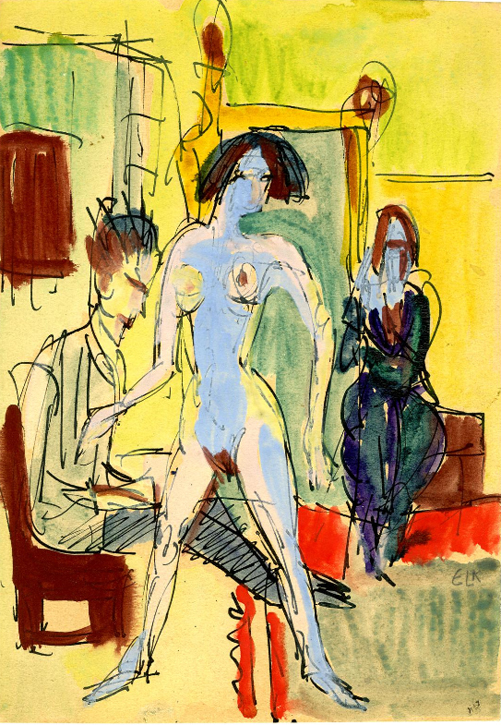

Untitled

c.1905–7, pen and black ink with watercolour and body colour by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880–1938)

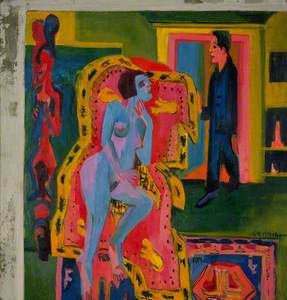

Reflecting on his artistic career, Kirchner wrote in a 1923 diary entry that he had wanted to 'bring art and life into harmony'. Beyond this, his paintings looked to the harmony of nature as a retreat from the dissonance and decadence of modern life.

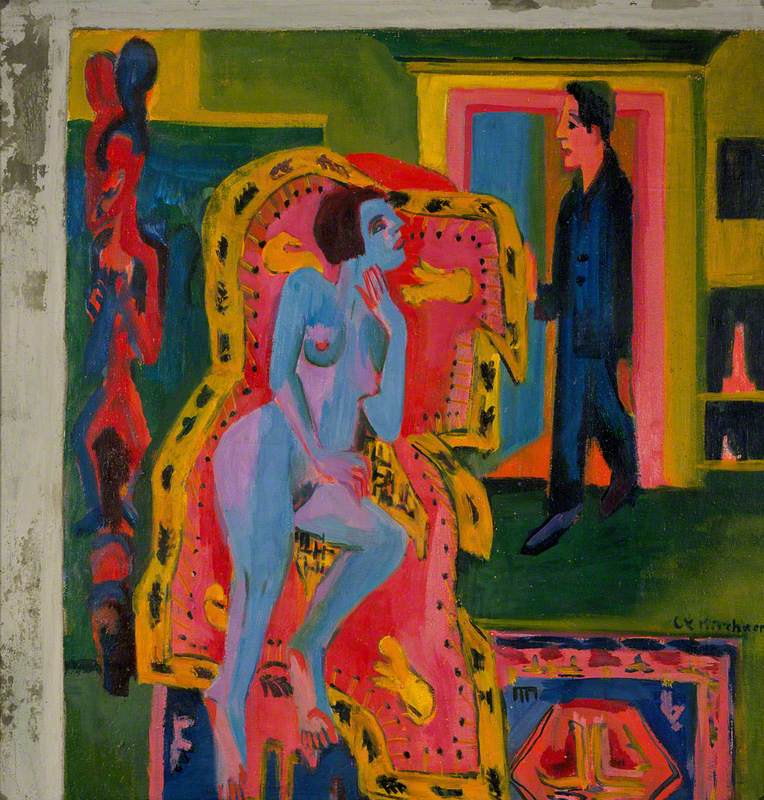

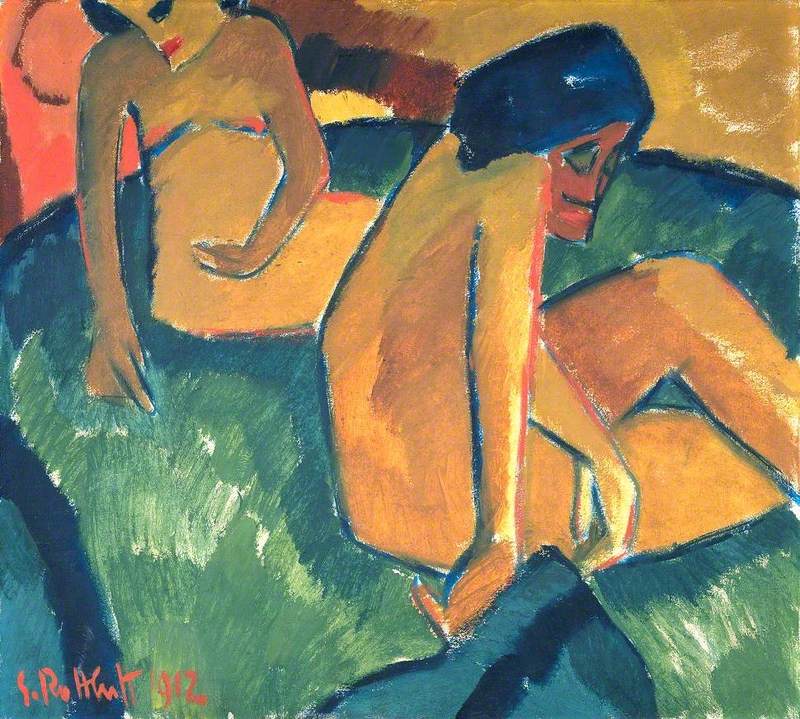

Countering oppressive social codes and materialism, Kirchner depicted man in stripped-back terms. Nudity is never gratuitous in Kirchner: it is at the heart of his artistic, and even political, creed. It represents freedom – from institutional oppression, and of man's spontaneous, raw selfhood.

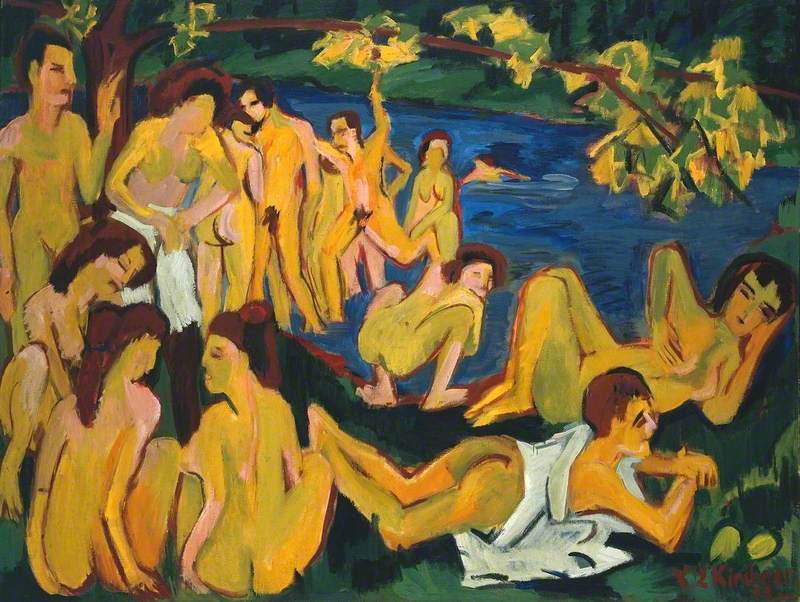

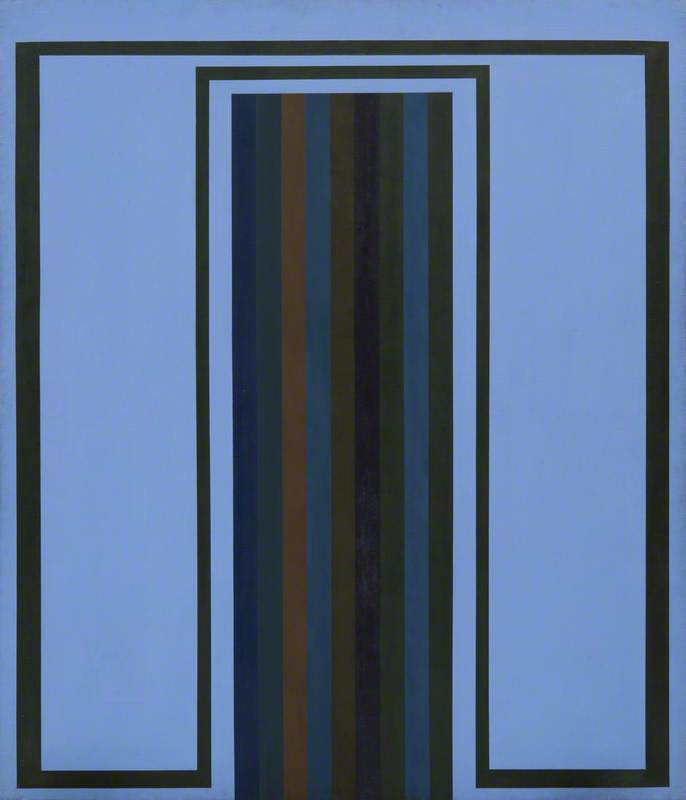

Bathers at Moritzburg (1909/1926) captures this impulse most clearly. The painting presents a kind of languid angularity – the latter belonging to the anguished artist, leisure to the bathers. Kirchner was committed to a return to nature as the counter-force to modern society and its decadent materialism.

Even while studying architecture at Dresden, nature (with its radical undercurrents) was at the top of Kirchner's agenda. Kirchner became friends with fellow architecture student Fritz Bleyl – with whom he soon founded the radical artistic group known as Die Brücke in 1905. Other founding members included Karl Schmidt-Rottluff and Erich Heckel, whose work can also be viewed on Art UK.

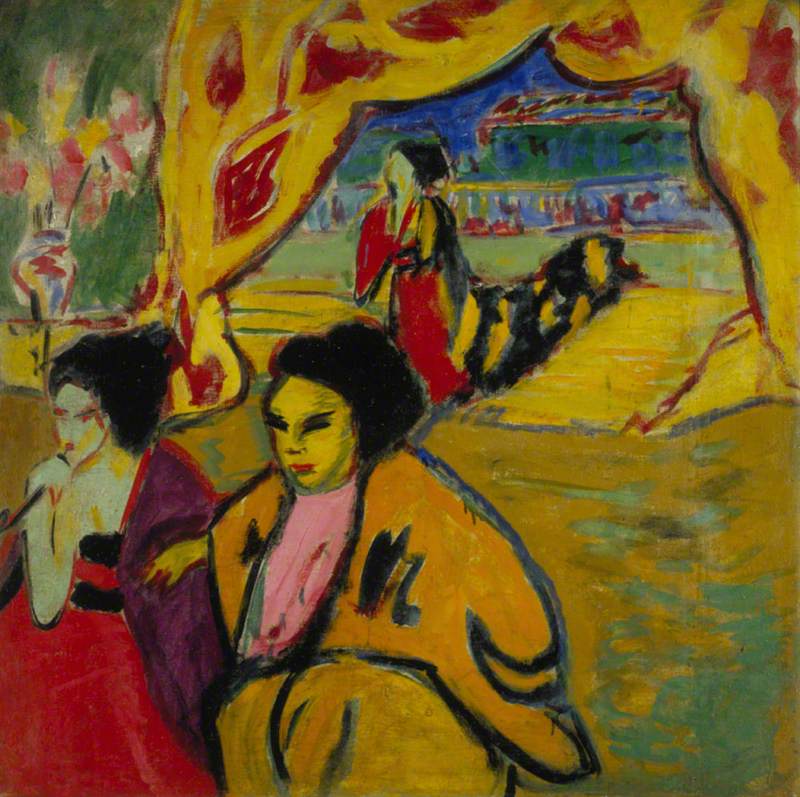

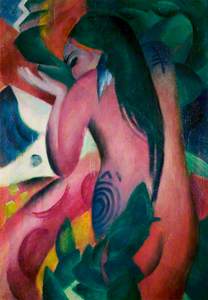

That return to nature contained radical intentions. Primitivism was an antidote to modernity's decadence. Exploring exotic alternatives provided a release from the present, and followed the widespread interest at the time in what was termed 'ethnography and tribal cultures'. Die Brücke's 1905 founding in Dresden also marked the birth of German Expressionism. The origin of the group's name is not certain, but it has variously been taken as an allusion to Nietzsche's work, the 'bridged' relationship between artist and patron, an early woodcut by Kirchner, and the group's desire to cross over to a new set of revolutionary ideas.

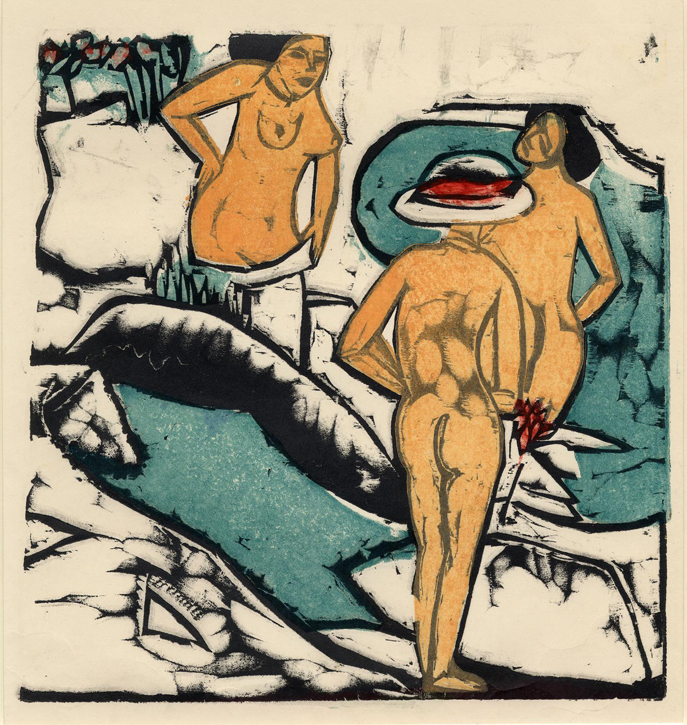

Image credit: British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

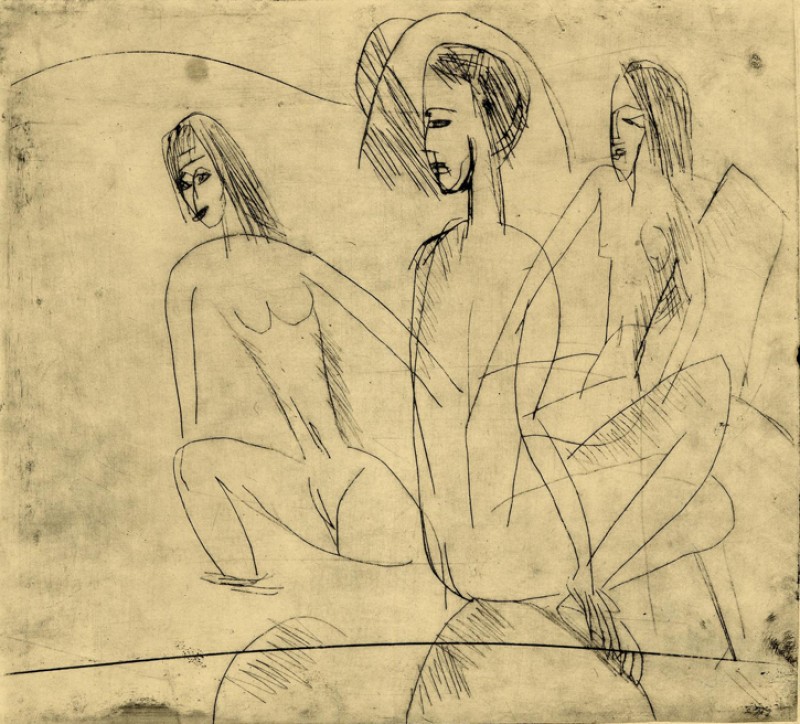

Three bathers at the Moritzburg lakes; seated, seen from behind

1909, etching by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880–1938)

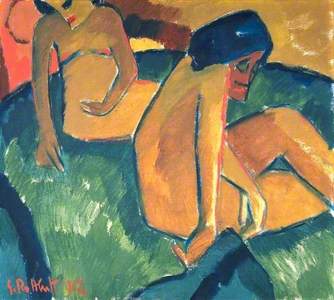

Kirchner and the members of Die Brücke spent the summers between 1909–1911 at the Moritzburg Lakes near Dresden. Their communal lifestyle there carried a spirit of ease, in stark contrast to the mood of the metropolis (even more apparent after Kirchner's move to the industrial Berlin in 1911). Artistically, their work was aligned with the 'cult of nature' emerging in Germany.

In terms of subject matter, Kirchner's Bathers at Moritzburg presents languid and reclining figures. In terms of artistic execution, however, we have almost the opposite: geometric angularity abounds. Significantly, Bathers at Moritzburg was repainted in 1926. Returning to his earlier work, Kirchner was dissatisfied with its style. The subject matter remained the same, but the colours became paler and the painting lost the dynamic feel of his early works.

The nude was repeatedly at the crux of Die Brücke group's work. For them, nude figures embodied moral and sexual freedom, unconstrained by stultifying social conventions. Yet in the very act of foregrounding these nudes, they implicitly acknowledged their own distance from that way of life. The works were viewed by an urban public, and ultimately looked back to an urban setting. The artists felt impinged upon by external authority, painting those nudes and verdant landscapes in attempts to reach out to a way of life they lacked. Their paintings are essentially tragic idylls: they convey thwarted aspirations. They were only ever artistic retreats, never a social reality.

Image credit: British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Women bathing between white stones

1912, colour woodcut on paper by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880–1938)

These apparently idyllic landscapes, then, carried distinctly unorthodox implications (implications that relate to the city rather than rurality). Beyond the shaded scenes, Kirchner's work recurrently manifests a deep-seated anxiety. When he does paint the city, we see internal and external agitation in explicit terms. The Moritzburg setting, of course, was sought not just for its beauty, but for its essential otherness from the city. Their heterodoxy was also characterised by a youthfulness, as declared in Die Brücke's founding manifesto. Accompanied by a woodcut, they announced in 1906: 'We believe in development and in a generation of people who are both creative and appreciative; we call together all young people, and – as young people who bear the future – we want to acquire freedom for our hands and lives, against the well-established older forces. Everyone belongs to us who renders in an immediate and unfalsified way everything that compels him to be creative'.

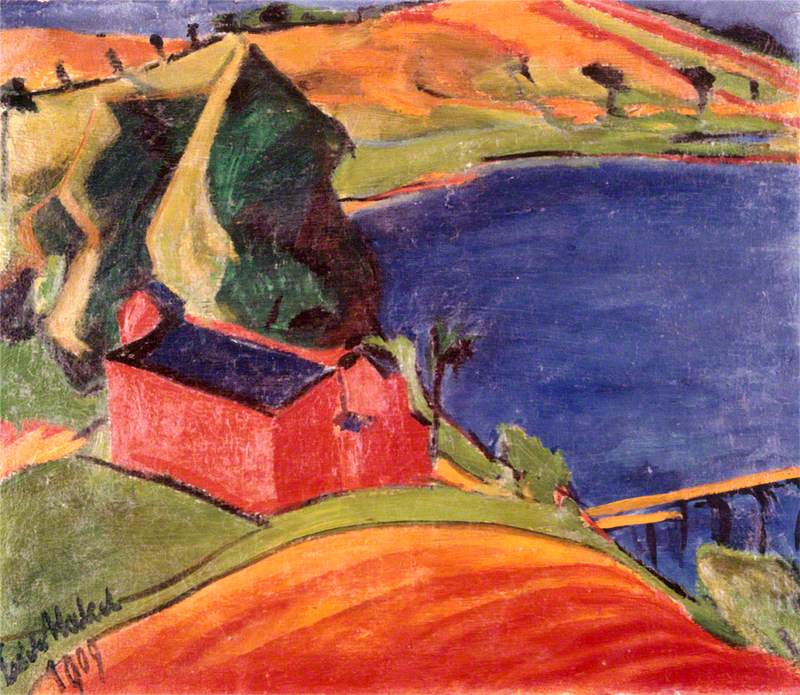

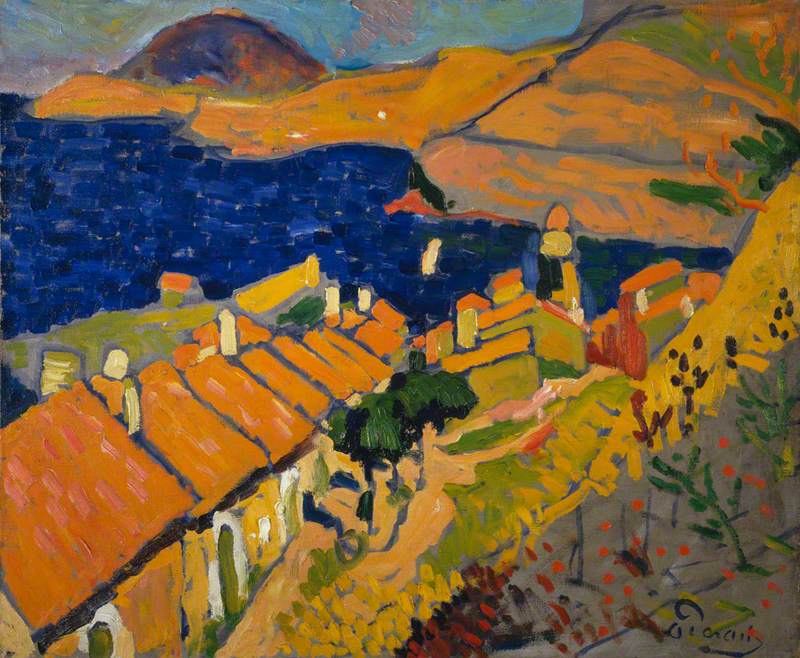

A similar colour palette permeates the group's work. Art UK has a number of pieces by Die Brücke group which demonstrate their dedication to nature, and to Moritzburg more specifically. Although Heckel's Lake near Moritzburg does not feature nude bathers, the inundating hills create a sense of calm that is itself alive. The colours are brighter, and the body of nature is infused with visual richness. Dated 1909, Heckel's painting has the brightness that Kirchner tempered when repainting Bathers at Moritzburg.

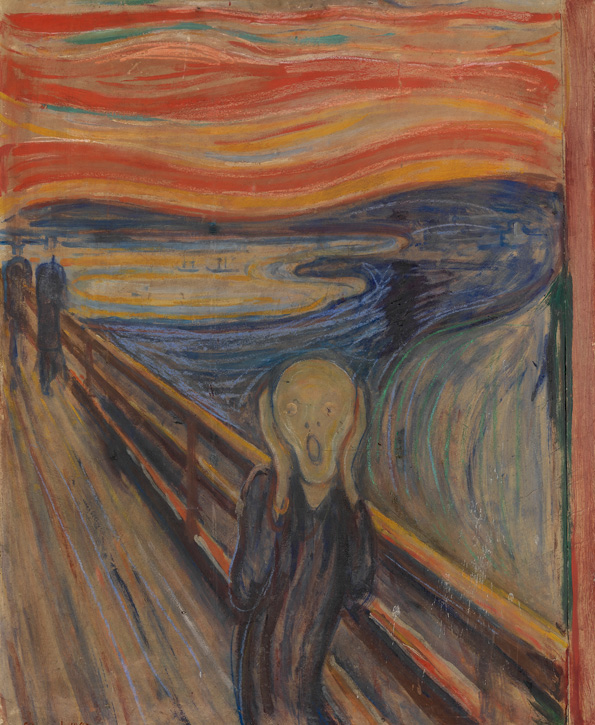

Heckel was an admirer of Edvard Munch and the garish hues of The Scream (1893) and its dynamic, broad brush strokes make for apt comparison with Heckel's Lake near Moritzburg. Crucially, however, Heckel's painting is situated outside the city and, by extension, essentially outside the debased modernity.

Image credit: National Gallery of Norway, public domain (source: Wikimedia Commons)

The Scream

1893, oil, tempera and pastel on cardboard by Edvard Munch (1863–1944)

By virtue of this, Heckel depicts not The Scream of Nature (Munch's full title) but rather a scene of natural ease. Munch's 1892 diary entry highlights the city's role in his inspiration for The Scream: 'One evening I was walking along a path, the city was on one side and the fjord below. I felt tired and ill…I sensed a scream passing through nature'. When tarnished by modern decadence, nature screams. Moritzburg, by contrast, represented an unspoilt natural sanctuary.

Kirchner's book, Chronik der Brücke, provoked the end of the already fracturing group. Ever since members of the group had moved to the industrial Berlin in 1911, they had begun to grow apart. The city was anathema to Die Brücke both within their paintings' themes, and as a setting for the dynamic of its members. 1913 marked their conclusive dismantling. Shortly after, Kirchner returned to the remote island of Fehmarn, where he discovered milder, richer colours and a strictness of artistic form (subsequently used in his repainting earlier works).

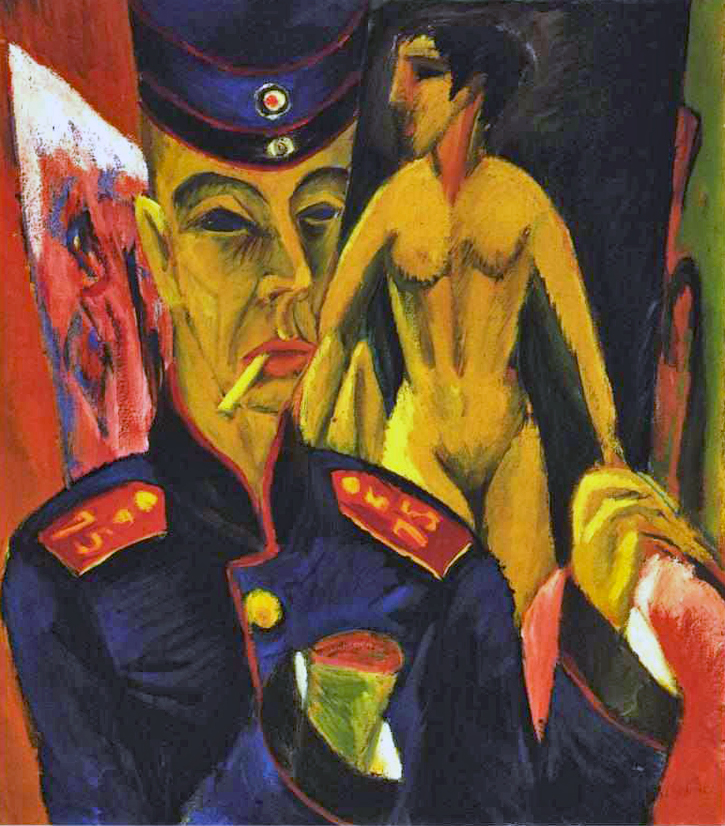

Image credit: Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin, Ohio, public domain (source: Wikimedia Commons)

Self-portrait as a Soldier

c.1915, oil on canvas by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880–1938)

Diagnosing modernity, Die Brücke's work was also an omen of what was to come. When the Nazis assumed power, the artists were persecuted and their work was classified as 'Entartete Kunst', or 'Degenerate Art'. Rather ironically, hordes of people queued to see the art out of interest more than disparagement, as Hitler had intended.

The 1937 'Degenerate Art' exhibition – organised in an attempt to vilify their work – featured a number of works by Kirchner. He was subsequently expelled from Berlin's Academy of Arts and in 1938, increasingly disturbed by the state of modernity, Kirchner took his own life.

Alice Theobald, Oxford University graduate

For more information on the German Expressionists, see Ashley Bassie, Expressionism, Parkstone International, 2008, New Walk Museum & Art Gallery, Leicester Arts and Museums Service, and Simon Theobald Ltd.