The Highland Clearances – known as Fuadaichean nan Gàidheal in Gaelic (the eviction of the Gaels) – is the name given to two waves of forced displacements of tenants in the Scottish Highlands and Islands (known as Gàidhealtachd in Gaelic) between the 1750s and the 1860s.

This forced emigration was the result of a number of human and environmental factors, including starvation caused by failing harvests, increased rents by exploitative landlords, and the introduction of widespread sheep grazing to replace subsistence farming methods – all aided by false promises of a life of plenty in the 'new world'. It was primarily the poorest tenants who were forced off their ancestral lands, often through violent means.

In the initial phase, the Clearances involved the break-up of the traditional townships (bailtean), whose inhabitants were then moved from the straths and glens of Scotland's interior to the coast, where they were expected to work in the kelping and fishing industries.

However, the economic downturn that began in 1810 ushered in the second phase, where landlords expelled tenants from their land and paid for their forced passage out of Scotland. This reached its height during the Highland Potato Famine of 1846–1855, which occurred in tandem with The Great Famine in Ireland.

Both of these events caused mass emigration and the formation of significant diasporic communities in Canada and the United States, as well as causing a population surge in the burgeoning industrial hub of Glasgow. Between the 1770s and the 1850s, it is estimated that at least 200,000 Highlanders were forced off their land, with at least 70,000 of those forced to emigrate.

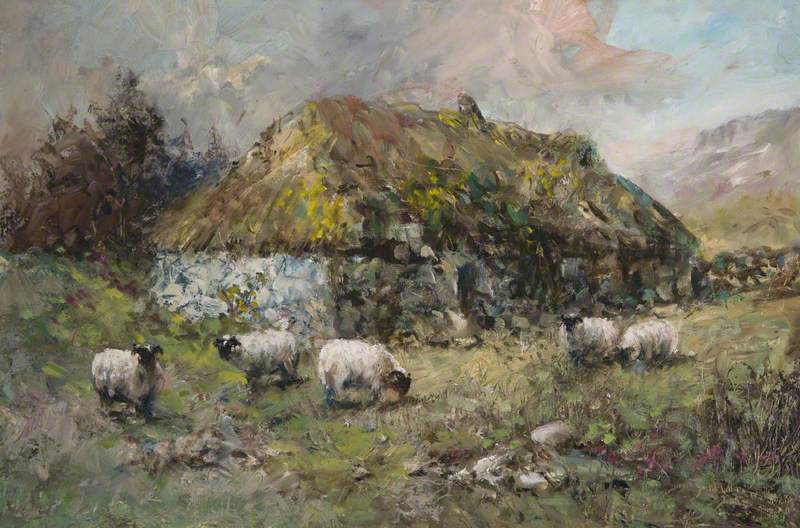

The effects of the Clearances are still felt today within Scotland. The landscape of the Highlands is still scarred by the evidence, with abandoned, ruined settlements, formerly called townships, littering the glens, straths and machair of northern and western Scotland.

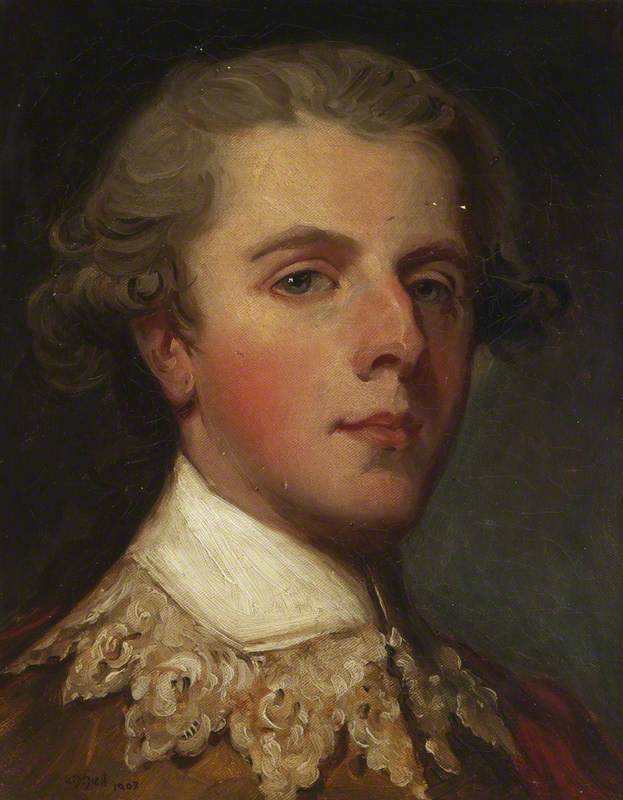

For contemporary Highland communities, the Clearances remain a contentious issue. Perhaps the most infamous landowner implicated with the Highland Clearances is George Granville Leveson-Gower, 1st Duke of Sutherland.

Leveson-Gower acquired a large amount of land upon his marriage to the Duchess of Sutherland, whose family had made their fortunes from a collection of slave plantations in Jamaica. He and his wife were responsible for the clearance of hundreds of people from his estate, and he remains a controversial figure to this day.

In 1994, a former Scottish National Party councillor from Inverness requested the removal of a statue of Leveson-Gower that stands near Golspie; when this was refused, they requested that the statue be relocated to Dunrobin Castle (where the Duke is buried) and that plaques be installed in its place that tell the history of the Clearances.

However, the statue still stands, despite repeated instances of vandalism (including an attempt to dynamite it in 1994) and a failed attempt by protestors to topple the statue in 2011.

Memorial to Duke of Sutherland (1758–1833)

('The Wee Mannie') 1837

Francis Leggatt Chantrey (1781–1841) and William Burn (1789–1870)

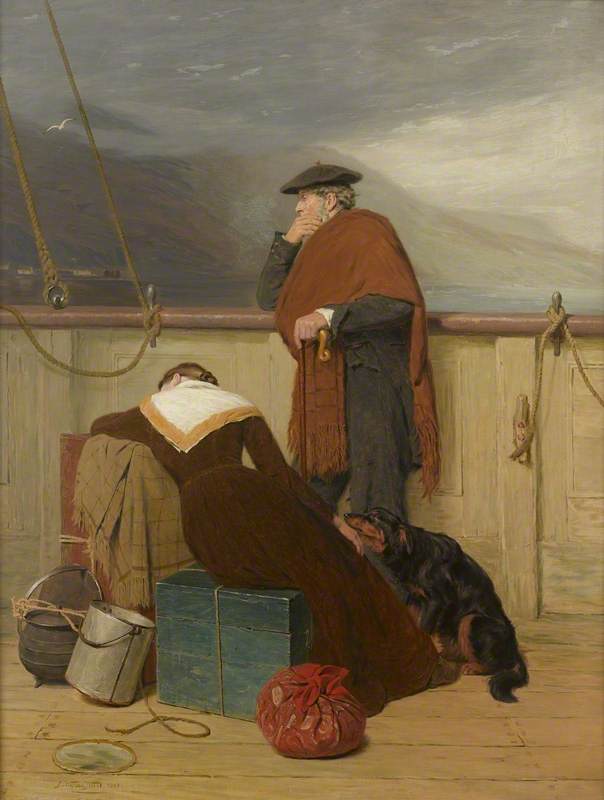

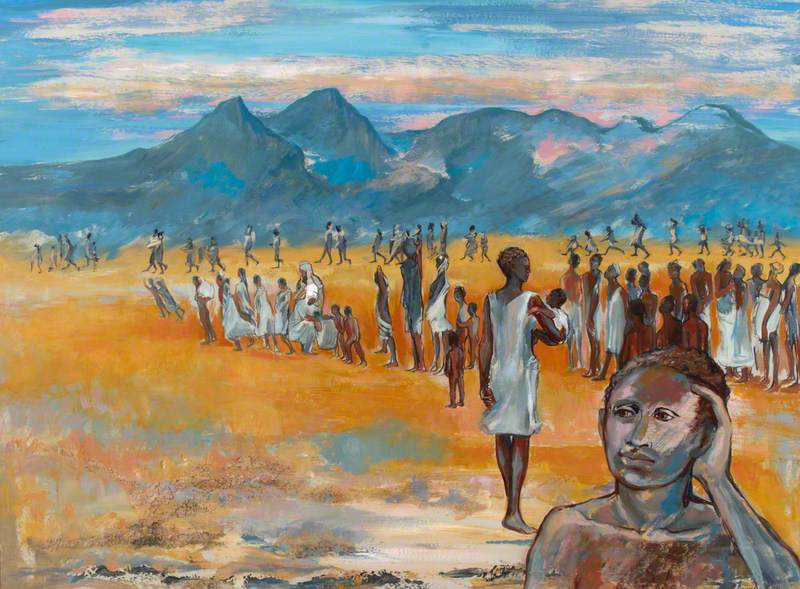

There is also a wealth of artistic interpretations of the Highland Clearances, particularly paintings, that capture the tragedy of these forced removals. There is an epic, almost Baroque-style feel to Thomas Faed's The Last of the Clan, with the theatrical stances and costumes of the subjects, the stormy seas in the distance charged with tragedy and longing.

Meanwhile, John Watson Nicol's Lochaber No More feels more staid, sedate, melancholic – almost an acceptance of defeat. The couple's meagre belongings – a large cooking utensil, a bucket, a cotton sack of clothes along with a loyal dog at their feet – point to an impoverished life. The man looks back to the shore, where a slew of grey clouds are crawling over the mountain and descending towards the sea – a worrying omen for their journey.

Gerald Laing's 2007 sculpture The Emigrants, which stands near Helmsdale, is particularly evocative of the ancestral severing that the Clearances created. While the male kilted figure looks steadfastly towards an unknown destination, his child looks to him, begging for reassurance, while the woman, swaddling a baby, looks back to what they have endured, and what they have lost.

It is important to note that in all these paintings and sculptures – all by male artists – there is a distinct gender dynamic. In these artworks, women are rendered invisible, inferior, or dependent on a male figure. This points to misogynistic attitudes towards women during this period in Scotland and across the British Isles – but it could also point to the fact that initially, only able-bodied men were sent to the colonies. Women, as well as children and the elderly, would have to wait before they could join them.

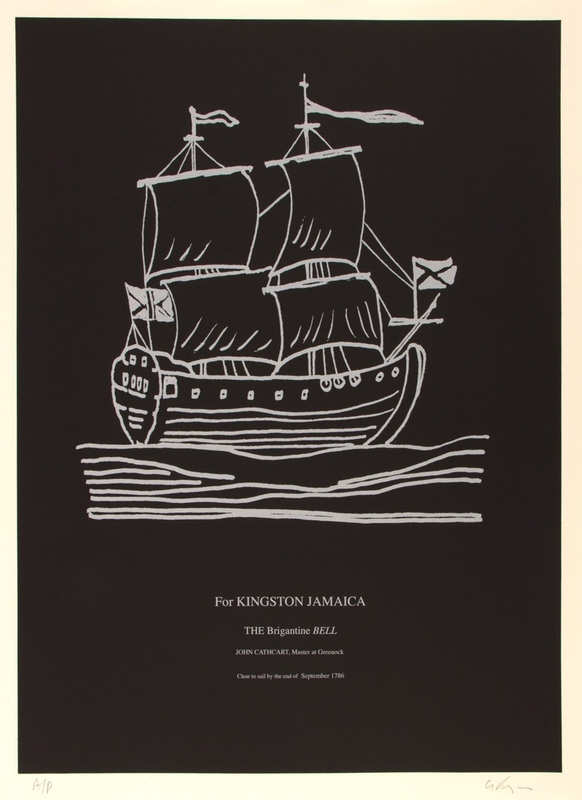

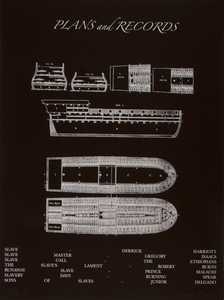

However, what is less well recognised is the entanglement of the Highland Clearances with the transatlantic slave trade within the larger global web of the British Empire. The land acquired by a new generation of landowners – those who pushed the Highlanders off their ancestral lands – was often purchased from the proceeds of slavery from plantations in Jamaica, Barbados and Guyana, many of which were owned by Scots.

The phenomenon of 'absentee ownership' – where plantation owners did not live in the West Indies – is a notable feature of Scotland's involvement in Caribbean plantocracies, which has allowed for cultural amnesia about the nation's role in the slave trade. During this period, both in the Caribbean and in the Highlands, we see a determined focus on intense resource extraction from the land through the brutal exploitation of people – administered by the same culprits.

It is worth noting that this comparison is not new. An eyewitness account from a violent clearance that took place on the island of Barra in 1851 said: 'Were you to see the racing and chasing of policemen, constables and ground officers pursuing the outlawed natives you would think, only for their colour, that you had been by some miracle transported to the banks of the Gambia on the slave coast of Africa.'

Even during this period, it is evident that there was an awareness of the brutality of the slave trade among rural Scottish communities (while slavery had ended in British colonies by this point, other European powers continued in the trade of enslaved Africans until the turn of the twentieth century).

A number of Scottish figures attest to these transatlantic connections. One of them – and one of the most infamously cruel – was John Gordon 4th of Cluny, who is notable for his particularly violent acts during the Clearances. Cluny also owned six plantations on the island of Tobago and, upon the abolition of slavery in British colonies in 1833, he was 'compensated' for these plantations and the nearly 1,400 enslaved people who toiled on them.

Meanwhile, in 1851 on the island of Barra, people were called to meetings in the island's village halls by Gordon, on the pretext of discussing rent payments. Those who did not attend were threatened with a fine if they did not attend this supposed 'meeting'. When they got to the meeting places they were tied hand and foot by the police, thrown onto ships and sent to America with nothing other than the clothes on their backs. A witness to the scene, a woman named Catriona Ni Phee, graphically describes this event:

'I have seen the townships swept, and the big holding being made of them, the people being driven out of the countryside to the streets of Glasgow and to the wilds of Canada, such as them that did not die of hunger and plague and smallpox while going across the ocean. I have seen the women putting the children in the carts, which were being sent from Benbecula and the Iochdar to Lochboisdale, while their husbands lay bound in the pen and were weeping beside them, without power to give them a helping hand, though the women themselves were crying aloud and their little children wailing like to break their hearts. I have seen the big strong men, the champions of the countryside, the stalwarts of the world, being bound on Lochboisdale quay and cast into the ships as would be done to a batch of horses or cattle in the boat.'

Racism and eugenics played a significant part in how both of these historical events unfolded – although obviously at very different magnitudes and with very different outcomes. One Lowland newspaper during the time of the Clearances reported: 'Ethnologically the Celtic race is an inferior one and, attempt to disguise it as we may, there is ... no getting rid of the great cosmical fact that it is destined to give way ... before the higher capabilities of the Anglo-Saxon.'

This view – that the Highlanders' culture and identity were both other and inferior – was common among the Scottish and English aristocracy and landowners. Although it is vital to recognise that the momentous scale, brutality, timeframe and legacy of the transatlantic slave trade is unparalleled in human history, connected events such as the Highland Clearances can help us to understand how eugenicist and racist attitudes impacted communities across the globe on minor and macro scales.

Harvey Dimond, freelance writer

This content was supported by Creative Scotland