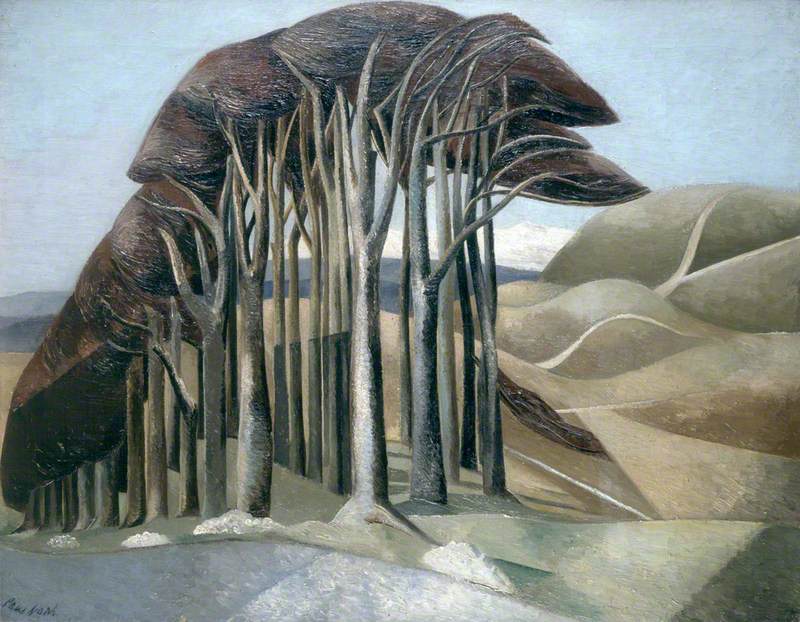

At first glance this painting looks ordinary, its saving grace perhaps the beautiful shot of bright blue pigment at the top right-hand side.

Littlehampton

oil on canvas by Emily Beatrice Bland (1864–1951)

However, the fact that two-thirds of the work is sky makes it equally a painting about sky which speaks to us of Constable, and a love of the changing patterns of the clouds above the land.

Detail of 'Littlehampton'

oil on canvas by Emily Beatrice Bland (1864–1951)

It's a seriously rumbustious sky, with some of the white lead paint laid on with a palette knife and other parts with grey overlays scumbled together.

The Beach at Tourgéville-les-Sablons

1893

Eugène Louis Boudin (1824–1898)

It has the breezy feel of paintings by Eugène Louis Boudin (1824–1898), not least because of the treatment of the foreground figures that appear to us as deftly manipulated blobs of colour.

The Harbour at Lorient

1896, oil on canvas by Berthe Morisot (1841–1895)

There is also a touch of Berthe Morisot (1841–1895) manifest in the detailing which has been dexterously and quickly laid down.

Detail of 'Littlehampton'

oil on canvas by Emily Beatrice Bland (1864–1951)

These foreground figures are both viscous and ambiguous, although one can make out a couple with hats and an umbrella.

Closer inspection reveals a person on a bike, a little girl posting a letter, a horse-drawn carriage and further away someone pushes a pram (they could be in the dark uniform of a nurse or nanny with a white cap). A dog prances in the middle ground of quiet open space that skirts the architecture with the main focal points of lighthouse and windmill.

Detail of 'Littlehampton'

oil on canvas by Emily Beatrice Bland (1864–1951)

Two sets of mauve-grey roofed cottages surround the latter and, to their left, we see the turquoise-blue roofed lighthouse. We can observe a series of masts, the first with a red flag, connected to moored sailboats, almost as if we were looking out from our own lighthouse viewpoint.

This robust little painting provides us with a warm and delicate snapshot of time gone by. It's not a nostalgic view but rather a pragmatic one that records actions that no longer exist. Letter posting becomes rarer today and nannies in uniform are a curiosity, windmills, horse-drawn carriages and working sailboats are no longer used, while yachts are strictly for leisure and often for the wealthy.

Detail of 'Littlehampton'

oil on canvas by Emily Beatrice Bland (1864–1951)

The Littlehampton windmill was demolished shortly after this work was painted – it is now forgotten. It stands here as a structure from another world; a world before GPS, accurate weather forecasting and computers. Here there are no cars in evidence, as in the 1930s these were still a novelty. One can tell the period clothes by the below-knee length of dress, and make out the shape of a broad-brimmed hat and trilby.

Detail of 'Littlehampton'

oil on canvas by Emily Beatrice Bland (1864–1951)

Today the park is known as Harbour Park, Butlin's, and it remains a site of leisure and play. The painting has a beautiful sense of space and perspective. The road sits parallel to our view of the scene and grounds our eyes, securing the layering of successive horizontals that meet the sea to the left, and the same grey road takes our eyes to the right, going off at a tangent into the distance. It is very wide-angle, suggesting a photographic panorama but using the drama of paint to evoke the bluster of a windy day. It is at once ordinary and special, public and private, a mundane yet intimate moment in time.

Why is it that some artists stay in the spotlight and others who have experienced lifetime recognition fade away? Some artists capture the zeitgeist with their work, somehow managing to characterise and visualise the essence of the period in which they live. This may create a spot for them as part of the pantheon of recognised artists, and go towards securing their position in the hall of fame. However, it does not guarantee a place, as fashion and art are fickle and subject to the same rules of fortune as everything else.

Women artists have, by the nature of their historical struggle for equality, found the competition for long-term recognition tougher, and their names occur less in the pages of art history books, sometimes being erased from the canon altogether. Much like the functioning windmill in her painting, Emily Bland was relatively successful during her lifetime, but her name has faded and is almost erased. Born in Lincoln in 1864, in the 1890s she studied under Henry Tonks and Frederick Brown at the Slade School of Art, and she exhibited at the Royal Academy.

Today 23 of her artworks can be seen in public collections – including the Walker Art Gallery in Liverpool, The Herbert Art Gallery and Museum in Coventry, Manchester Art Gallery, Ferens Art Gallery in Hull, and the Royal Academy. These works testify to her original eye and skill.

Liz Rideal, artist and writer