In eighteenth-century Europe, amid political turmoil and changing ideas of identity, lifelong friends James Byres and Elyza Fraser managed to carve out a space where public expectations and private lives could coexist. Their creative projects and domestic designs offer a fascinating window into their personal circumstances, separate same-sex relationships and long-lasting friendship, all sustained by the unconventional realities they forged for themselves.

Image credit: National Trust for Scotland, Castle Fraser, Garden & Estate / Aberdeen Art Gallery & Museums

Left: Eliza Fraser of Castle Fraser (detail), right: James Byres of Tonley (detail)

Left: oil on canvas by Henry Raeburn (1756–1823), right: 1782–1791, pastel on paper by Hugh Douglas Hamilton (1739–1808)

James and Elyza were born in 1733 and 1734 respectively into Catholic families of the landed gentry in Aberdeenshire, Scotland. Their families' Jacobite allegiances – dedicated to restoring a Catholic monarch to the Scottish throne – instilled in them a strong sense of identity and loyalty in the face of uncertainty.

The Jacobite uprising of 1745, culminating in the catastrophic and decisive defeat at the Battle of Culloden, marked the collapse of the Jacobite cause. It forced James and Elyza onto unique paths of personal and public survival and, I believe, set the stage for the resilience and self-determination that would define their lives.

Elyza Fraser's family coordinated a division of loyalties during the Jacobite uprising, with some members supporting the Jacobites and others aligning with British government forces. Connections to the British forces proved crucial in the tumultuous aftermath, offering protection and helping the family avoid retribution.

The death of Elyza's eldest brother at Culloden triggered a chain of events leading to Elyza inheriting Castle Fraser, marking a significant turning point in her life. As a female laird in the patriarchal, male-dominated Scottish Highlands, she gained rare autonomy. Free from societal pressures to marry, Elyza chose a life of independence and formed a lasting partnership with another woman, Mary Bristow.

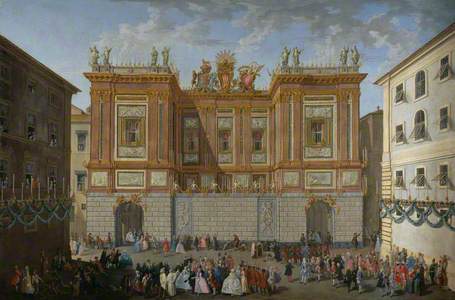

Meanwhile, in the aftermath of Culloden, the Byres family fled to Europe. They eventually settled in Rome and joined a cluster of other displaced Jacobites centred around the Scottish Catholic court-in-exile. It was here James developed his expertise in Italian art. He became a respected art dealer and cicerone, guiding British aristocrats on their Grand Tours.

Image credit: National Galleries of Scotland

Prince James Receiving his Son, Prince Henry, in Front of the Palazzo del Re c.1747–1748

Paolo Monaldi (1720–1799) and Pubalacci and Louis de Silvestre (1675–1760)

National Galleries of ScotlandFor James, the Grand Tour offered more than just an education in art and antiquities – it also served as a playground for homosocial relations, allowing men to form and explore bonds under the guise of cultural pursuits. In this environment, James Byres and his long-term partner, Christopher Norton, explored and expressed their individuality and sexuality through their social networks, academic studies and artistic projects.

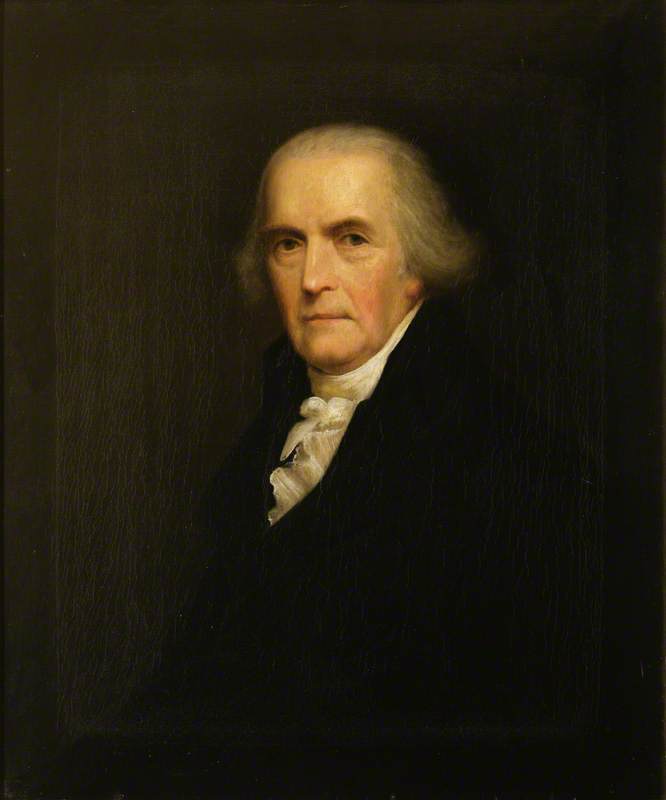

Image credit: National Trust for Scotland, Castle Fraser, Garden & Estate

James Byres of Tonley (1734–1817) c.1810

British (Scottish) School

National Trust for Scotland, Castle Fraser, Garden & Estate

Image credit: Aberdeen Art Gallery & Museums

Christopher Norton (d.1799) 1760–1764

Nathaniel Dance-Holland (1735–1811)

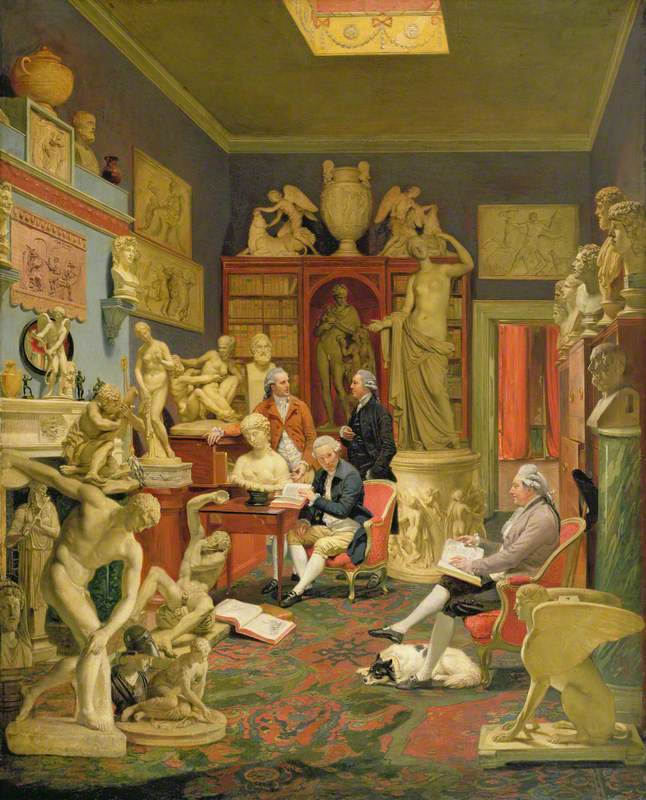

Aberdeen Art Gallery & MuseumsJames' role within the Grand Tour experience is immortalised in the group portrait below. He is pictured second to the left, among other British contemporaries: a testament to his prominence within Britain and Italy's artistic and social networks. In Rome, his reputation as a leading figure in these circles placed him in the company of celebrated figures such as Angelica Kauffmann, Allan Ramsay and Pompeo Batoni. Batoni painted a portrait of James' sister, which James kept in his collection.

Image credit: National Trust Images

A Grand Tour Group of Five Gentlemen in Rome c.1773–1774

John Brown (1752–1787) (attributed to)

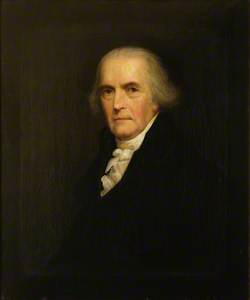

National Trust, SpringhillBack in Britain, he also played a pivotal role in shaping the tastes of the gentry and influencing the interiors of their homes. James was involved in introducing prominent figures such as historian Edward Gibbon, artist Henry Raeburn, and the collector Douglas, 8th Duke of Hamilton to the masters and masterpieces of Italian art. Antiquary Charles Townley wrote to James in August 1781 with an indication of James' prestigious networks: 'Mr. Zoffani is painting, in the Style of his Florence tribune, a room in my house, wherein he introduces what Subjects he chose in my collection'.

Image credit: Bridgeman Images

Charles Townley and Friends in His Library at Park Street, Westminster 1781–1790 & 1798

Johann Zoffany (1733–1810)

Towneley Hall Art Gallery & MuseumElyza's passion for art and design, perhaps ignited by a visit to the Byres family in Rome when she was young, was later shared with Mary. The two women met at Clifton Spa in Bristol on 18th June 1781: a date they continued to celebrate annually. They quickly formed a deep connection and, over the next few years, travelled extensively across continental Europe, visiting Spain, Monaco, Portugal, Switzerland, France and Italy, probably visiting James in Rome. I believe Elyza and Mary's travels provided a framework to explore their bond through a more liberal lens, offering greater freedom from the constraints and suspicions they faced in Britain.

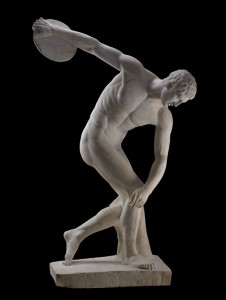

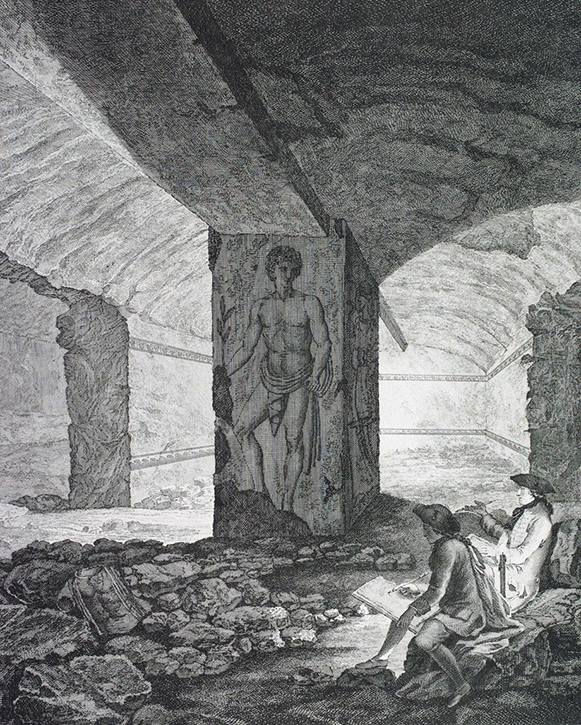

This was certainly the case for James. His fascination with the Etruscan civilisation stemmed not only from their cultural erasure by Rome, which paralleled the Jacobite defeat and suppression, but also from their art, which celebrated intimacy, fluid gender roles and depictions of male beauty. James' study of the Etruscans, published posthumously, included engravings of drawings by Franciszek Smuglewicz, the artist who painted James's family portraits.

Image credit: University of Aberdeen, CC BY 4.0

Plate in Byres' 'Hypogaei, or sepulchral caverns of Tarquinia, the capital of antient Etruria...'

1842, engraving by Christopher Norton (d.1799) from drawing by Franciszek Smuglewicz (1745–1807)

One of these drawings possibly depicts James and Christopher sitting together, sketching a semi-naked male youth painted within an Etruscan tomb. This scene highlights James' intellectual and personal connection to a civilisation whose experiences resonated with his own. This connection is further reflected in his art collection – the below relief, reminiscent of depictions of the emperor Hadrian, is possibly the one listed in the 1790 inventory of the apartment James shared with Christopher in Rome on the Strada Paolina.

Balanced with his public research, James' sexuality and relationships were subtly acknowledged in the intimate domestic arrangements of the Roman home. This is evidenced by portraits of James and Christopher by Hugh Douglas Hamilton. They are listed in the 1790 inventory as hanging together in the 'Writing Room'. Along with their chosen display arrangements, their poses suggest a subtle yet deliberate acknowledgement of their bond – hidden in plain sight.

In a remarkable acknowledgement of Christopher's role in James' wider domestic life, he is also included in a Byres family portrait – a rarity for someone outside traditional family structures. Two versions of the portrait by Franciszek Smuglewicz exist. I suspect that one was intended for public display and the other for more private settings.

In the first version, the family are painted in their home in Rome in 1767, with a view of the dome of St Peter's visible through the open window. The Byres family make up the foreground: his sister is dressed in mourning, and his seated mother and his father are positioned prominently. Christopher stands on the far right – an equal – gazing across the family scene at James.

Image credit: National Galleries of Scotland

James Byres of Tonley and Members of his Family c.1780

Franciszek Smuglewicz (1745–1807)

National Galleries of ScotlandIn the second version, the backdrop shifts to a stark, monochromatic grey that I believe intentionally emphasises symbolic elements. A portrait of Bonnie Prince Charlie in the left corner signifies the Byres' Jacobite allegiances, while a prominent relief of Ganymede and Zeus in the form of an eagle looms large in the centre of the background. The scene recalls the myth of Ganymede, a mortal man whom Zeus abducted as a lover. This imagery draws on the ancient Greek tradition of paiderastia, a socially recognised romantic bond between men and male youths.

Given James' extensive knowledge of art history, it seems obvious that this myth was deliberately included to acknowledge the nature of his relationship with Christopher within the Byres family structure. The two portraits are a powerful medium for expressing both overt and hidden meanings. When considered together, they reveal a careful balance between public acceptance and private authenticity.

Image credit: National Trust for Scotland, Castle Fraser, Garden & Estate

Henry Raeburn (1756–1823)

National Trust for Scotland, Castle Fraser, Garden & Estate

Image credit: National Trust for Scotland, Castle Fraser, Garden & Estate

George Chinnery (1774–1852)

National Trust for Scotland, Castle Fraser, Garden & EstateFor Mary and Elyza, years of travel deepened their connection and provided inspiration and affirmation for their relationship. The couple kept diaries reflecting on their travels and union, often writing poems revealing an intense devotion to one another. In a particularly poignant entry, Mary wrote, 'I am not capable of moderation towards my love – my joy, my grief – are all excessive – when you occasion them.'

As gentry ladies trained in French, Italian, Latin, and even Hebrew, Elyza referred to Mary in one poem as 'my amanda', a feminine Latin word meaning 'she who must be loved' or, in Hebrew, 'gift from god'. Their classical education likely helped them connect with figures like Sappho, whose legacy as a poet of love between women offered historical context for their bond. Eventually, though, Mary grew weary of their nomadic lifestyle, declaring in 1786 her decision to 'return home & give up my wandering life.' Despite this, their relationship endured.

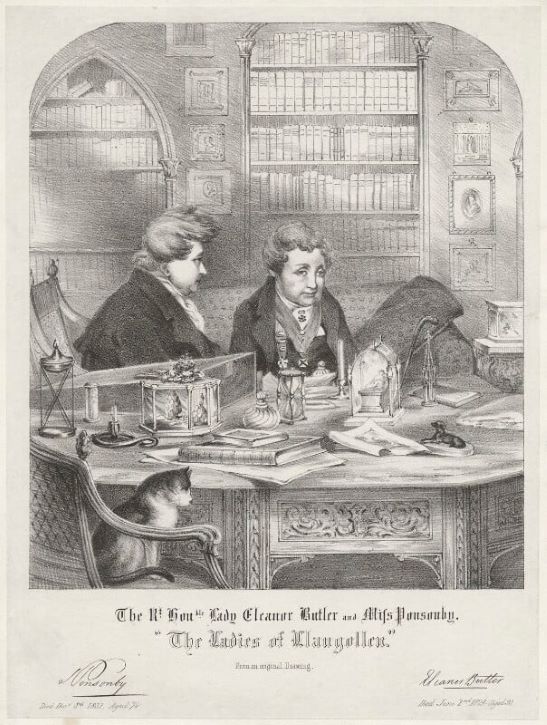

In 1792, aged 58, Elyza inherited Castle Fraser and invited Mary to live with her, solidifying their partnership with a shared domestic future together. Perhaps they were inspired by the Roman apartment shared by their friends James and Christopher. Given that they were both interested in poetry, I've also wondered if they had come across Anna Seward's popular 1796 poem Llangollen Vale which celebrated their renowned contemporaries Eleanor Butler and Sarah Ponsonby: a couple who had set up home together in 1780 and had a succession of dogs called Sappho.

Image credit: National Portrait Gallery London, CC BY-NC-ND 3.0

'The Ladies of Llangollen' – Sarah Ponsonby and Lady (Charlotte) Eleanor Butler

1836, lithograph by Richard James Lane (1800–1872), after Lady Mary Leighton, née Parker (1810–1864)

At Castle Fraser, Elyza and Mary shared private quarters in the 'Worked Room', a space typically reserved for the laird and his wife. It is believed the matching soft furnishings in this bedroom were handmade by Elyza and Mary, which further suggests the depth of intimacy between them. Today, their portraits hang together in this room, displayed in their gold frames, alongside one of James Byres, who moved back to Aberdeenshire in 1790.

While living together at Castle Fraser, Elyza and Mary not only focused on improving the castle to their tastes but also its grounds, with Mary acting as a co-proprietor in all but name. Her influence is still felt today in projects like 'Miss Bristow's Wood' and the gardening books she gathered during their travels, now in the castle library.

Image credit: National Trust for Scotland, Castle Fraser, Garden & Estate

James Giles (1801–1870)

National Trust for Scotland, Castle Fraser, Garden & EstateAfter Elyza's death, a draft of a deed was found amongst her possessions, revealing her intention to bequeath the castle and its estate along with the Fraser name, arms and title, to Mary. However, Mary's death in 1805 preceded Elyza's. She commissioned a memorial in the Bristow woods, inscribed: 'Farewell! Alas, how much less is the society of others than the memory of thee. Sacred to a memory that subsisted 40 years.' After Mary's death, Elyza fell into a deep depression and took to her bed for the rest of her life, sending a powerful message about the profound love they shared until the very end.

The lifelong friendship between James Byres and Elyza Fraser culminated in a final exchange: the personal gifts Elyza left James in her will – her 'carriage and best pair of horses' and a 'fine stone snuff box' – and his design and payment for her mausoleum.

Image credit: Martyn Gorman, CC BY-SA 2.0 (source: Wikimedia Commons)

The Fraser Mausoleum, dedicated to Elyza Fraser, Cluny Old Kirkyard, Aberdeenshire

1808, grey granite by James Byres (1733—1817)

James and Elyza demonstrate how expression through art and design can act as powerful tools for legitimising intimacy, love and commitment, during a time when those bonds were not – or could not – be written down. James and Elyza's lives demonstrate how creativity can transcend societal limitations and offer a lasting testament to deeply personal connections. Their legacy challenges us to rethink how we interpret relationships in the past, and recognise the power of art and design to reveal overlooked histories that enrich our understanding of history.

Indigo Dunphy-Smith, researcher and writer

As a queer woman and researcher working in historic houses, I'm constantly struck by how spaces hold the traces of the lives lived within them – lives that, despite the passage of time, still resonate with us today. This story was inspired by the projects of Historic England and the National Trust in uncovering queer histories. Thanks to the property staff at Castle Fraser.

This content was funded by the PF Charitable Trust

Further reading

Peter Davidson, 'James Byres: a Note on Catholicism, Jacobitism and Etruscans' in Judith Swaddling (ed.), An Etruscan Affair: The Impact of Early Etruscan Discoveries on European Culture, British Museum Research Publications, 2018

Emma Donoghue, Passions Between Women: British Lesbian Culture 1668–1801, Scarlet Press, 1993

Alison Duncan, 'Old Maids': Family and Social Relationships of Never-Married Scottish Gentlewomen, c.1740–c.1840, PhD dissertation, University of Edinburgh, 2012

Churnjeet Mahn, 'Travel Writing and Sexuality: Queering the Genre' in Studies in Travel Writing, 19, no. 2, 2015

National Library of Scotland, Byres-Moir Manuscripts, 'Inventory of Goods Left by James Byres in His Roman House, 1790'

George Sebastian Rousseau, Perilous Enlightenment: Pre- and Post-modern Discourses: Sexual, Historical, Manchester University Press, 1991

University of Aberdeen, 'Papers of Miss Elyza Fraser (1734–1814) of Castle Fraser: correspondence and notebooks'