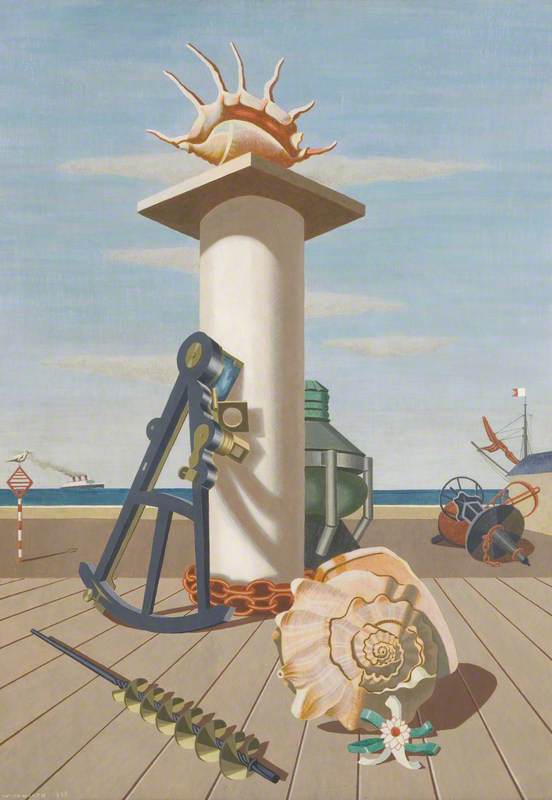

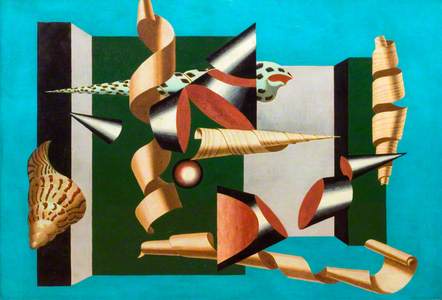

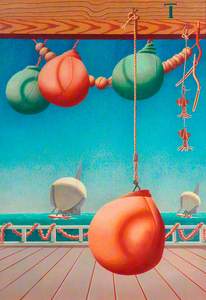

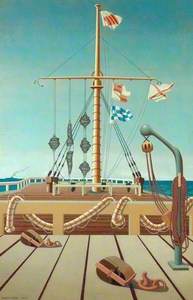

Bright Intervals depicts an assemblage of nautical-themed objects against an imagined seascape. It contains a blueprint with an elaborate curl at one end, an aneroid barometer, a seashell, a ball of tarred twine, serval fishing floats, a joiner's square, and a pair of binoculars peering out from behind a stoic white block. Each item is unique within the group, yet serves a distinct purpose of constructing, balancing or adding texture to the overall composition. They are presented in a vivid and purposeful manner, with a striking red ribbon adding a baroque flourish to an otherwise static scene.

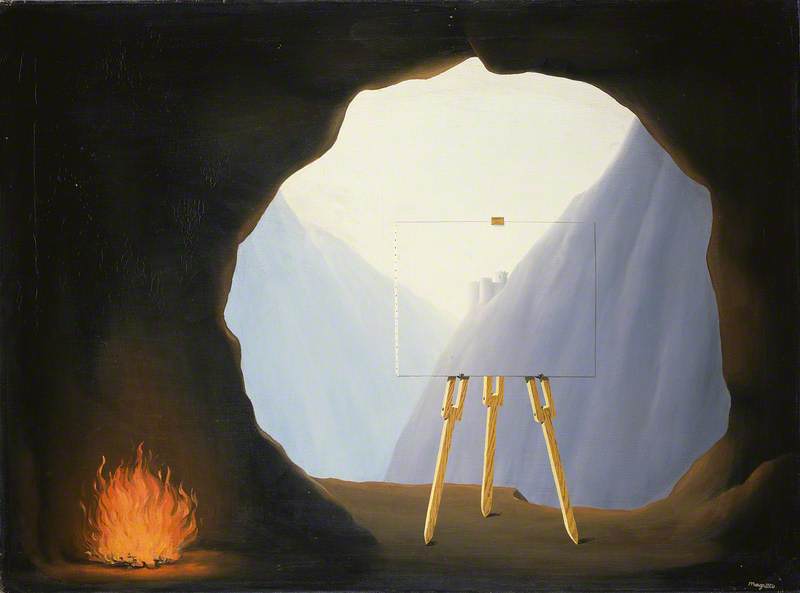

At once playful and meticulous, Bright Intervals is as captivating today as it was when Edward Wadsworth (1889–1949) first made it in 1928. At the time, its reproduction in Belgian arts magazine Variétés placed its creator within the European avant-garde, alongside the likes of Paul Klee, Giorgio de Chirico and René Magritte. It was exhibited in a commercially and critically successful solo show at Tooth Gallery in 1929, alongside other marine still lifes created by Wadsworth in the late 1920s.

The series presents eccentric still life compositions against strips of bright blue and green that evoke sky and sea. Mass-produced objects are juxtaposed with organic shapes, such as shells and flowers, and a white block is often utilised to create structure and balance. As seen in Bright Intervals, each item is carefully placed, and reproduced with the precision of a skilled draughtsman.

Indeed, quality draughtsmanship lies at the heart of Wadworth's work. He trained as an engineering draughtsman in Munich from 1907 to 1908, before studying at the Slade School of Art under Henry Tonks, who is renowned for his commitment to drawing. Wadsworth's appetite for precision was fed by these rigorous introductions to draughtsmanship, and combined with a zeal for perfectionism and hard work that imbued his Victorian upbringing in Yorkshire.

Yet, this highly disciplined approach achieves an almost dream-like hyper-realistic effect, and the viewer's perception is quietly destabilised by subtle manipulations of the composition. The boat in the background of Bright Intervals is pushed right up to the imagined interior space and appears small compared to the still life. Meanwhile, the joiner's square and fishing floats balance precariously on the white block and table edge. The resulting sense of uncanniness in images like this has often led to Wadsworth being aligned with surrealism. However, the artist refuted a singular association with the group, instead claiming an overall preoccupation with the odd and enigmatic nature of reality.

Such ideas may track back to Wadsworth's employment as a dazzle camouflage designer during the First World War. The unpredictable geometric pattern of dazzle camouflage on ships confused the enemy regarding their position and speed. Wadsworth was one of two dock officers in Liverpool supervising the dazzle camouflaging of almost 2,500 ships in 1918. During the last year of the war, the number of sunk British merchant ships dropped dramatically. Works like Bright Intervals show a continuing engagement with the trickery of human perception.

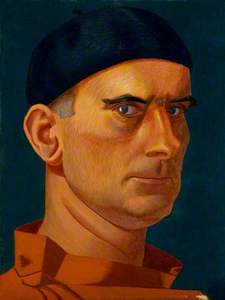

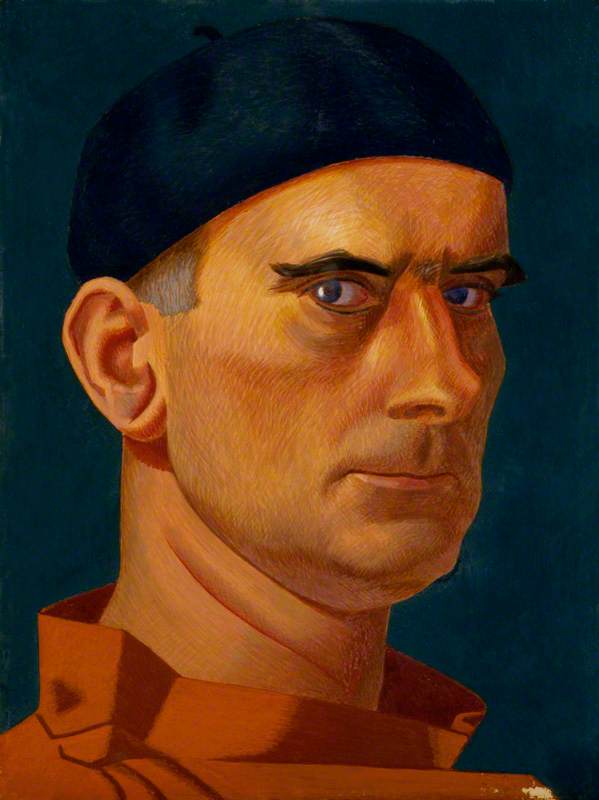

Edward Alexander Wadsworth

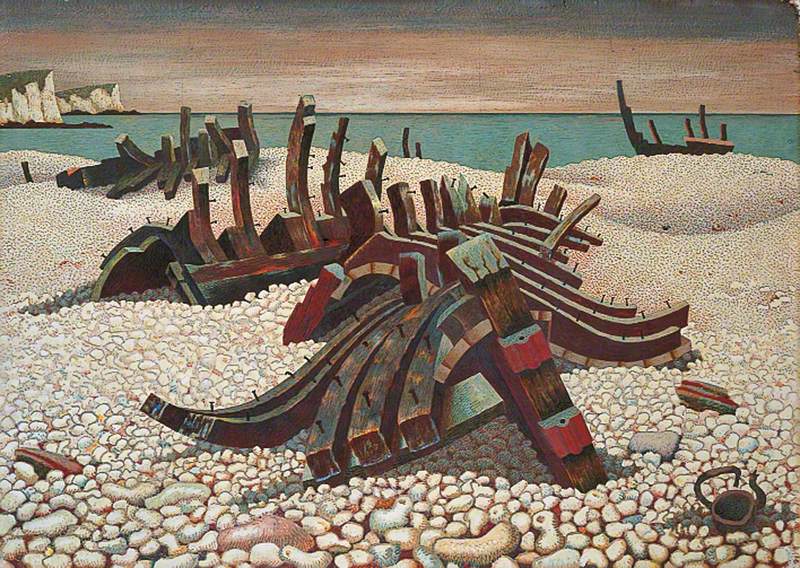

1937

Edward Alexander Wadsworth (1889–1949)

The post-war drive for rappel à l'ordre (or return to order) amongst artists may have been another reason for Wadsworth's reluctance to be part of an art movement. Driven particularly by French artists shaken by the war, rappel à l'ordre called for a re-engagement with art traditions that emphasised balance and accuracy. This ideal stood in contrast to experimental art movements that erupted before the war. The patient and precise nature of Wadsworth's still lifes fulfilled this need, creating order even as they embraced the strangeness of reality.

This effect was also helped along by Wadsworth's engagement with egg tempera. Unlike oil paint, this unforgiving medium dries quickly and is not easily altered, leaving little room for hesitance. Wadsworth thought it was ideal for creating quality paintings because it required a high level of intellectual engagement. In part influenced by vibrant frescos he saw during a trip to Sienna in 1923, he was also drawn to the luminosity of colour that could be achieved with tempera painting. This time-tested medium helped achieve the striking clarity of colour and line that makes Bright Intervals such a captivating image.

Throughout his career, Wadsworth moved through many stylistic phases. From the machine-like abstractions of his early Vorticist years, to almost visionary assemblages later in life, he refused to stay still for long. He strove to challenge the viewer's perception of everyday objects, seeking to express the spirit of modernity and pushing forward the potential of still life as a genre. This is nowhere more evident than in Bright Intervals, which Museum & Art Swindon has gladly loaned to Pallant House Gallery's illuminating assessment of still life in British modern and contemporary art.

Katie Ackrill, Collections and Exhibitions Officer, Museum & Art Swindon

This article was originally published by Pallant House Gallery in connection with their exhibition 'The Shape of Things: Still Life in Britain', available to visit until 20th October 2024