Take a blank sheet of paper. As soon as you make a mark on it – with a pencil, charcoal stick, brush, crayon, whatever comes to hand – something changes. That first mark sets the tone for the drawing. Here is a drawing by Carol Rhodes, called Pond Area.

Whichever pencil mark got the drawing going – maybe the first, tentative lines of the T-junction, or the outline of the large pond – it immediately altered the rest of the sheet. It told the rest of the marks where to go. It established the scale and scope of the drawing: an aerial view, seen at too far a distance to make out much more than the general shapes of human habitation and natural forms. Those first touches of the pencil on the paper surface were marks of orientation: a way of saying you are here.

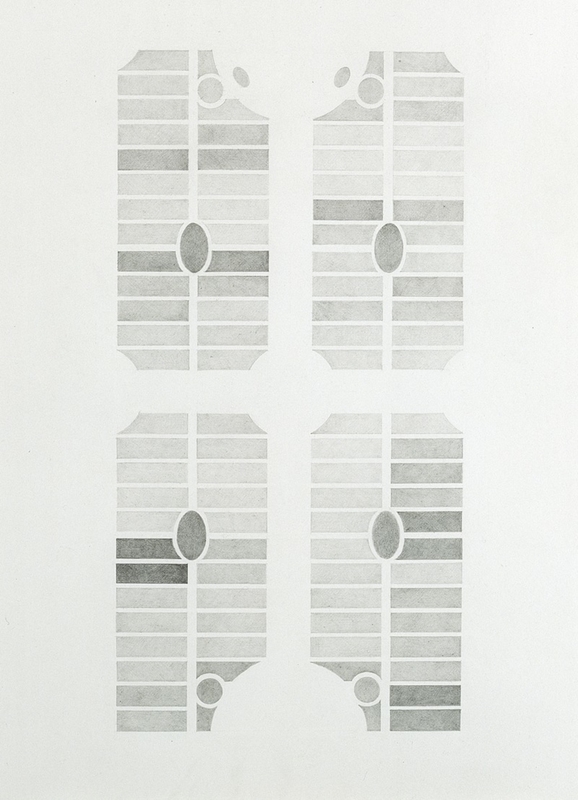

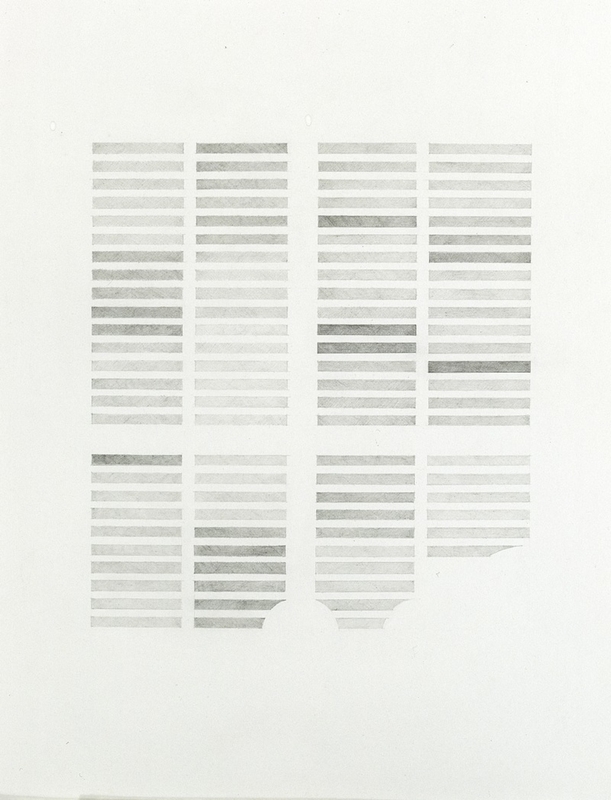

Alison Turnbull's Beds series does something similar. Here, the precise geometric arrangement of differently shaded horizontal bars and ovals, which sit in parallel to the paper surface, orientates our viewing differently. Where are we now? Above, perhaps. The drawing shows the layout of Oxford Botanic Garden, its diversity of tone indicating different plant species that would occupy each space. The effect is that of a plan, something removed from the actuality of the physical labour of making a garden grow. The tension between classification and unpredictability – which is fundamental to any study of the natural world – seems to be suggested in the way the drawing itself is made. Those feathery marks, contained in their careful boxes, might easily overspill them.

Drawing uniquely allows us to think in this way. Drawings, unlike almost any other form of art, keep the process of their making in view. Where paintings tend to involve a series of coverings – the loose early jabs of the brush, like clearing the painter's throat, are gradually silenced under layers of paint – drawings, however densely made, keep their history available. Rhodes' drawing encourages us to imagine the early moments of its production. You could see the paper as itself like an area of land. Like a developer's pencil, each line seems to carve up real space, delineating spaces of transport and habitation. Both the artist and the viewer seem held at bay.

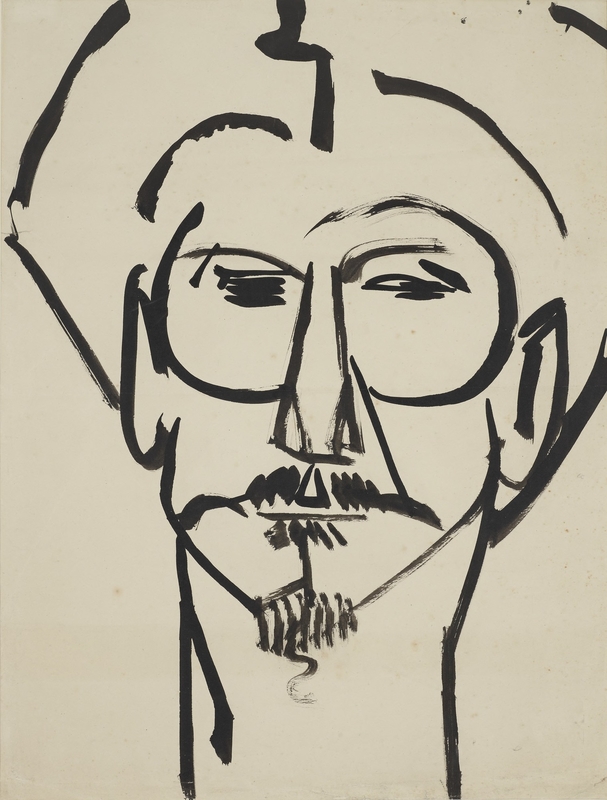

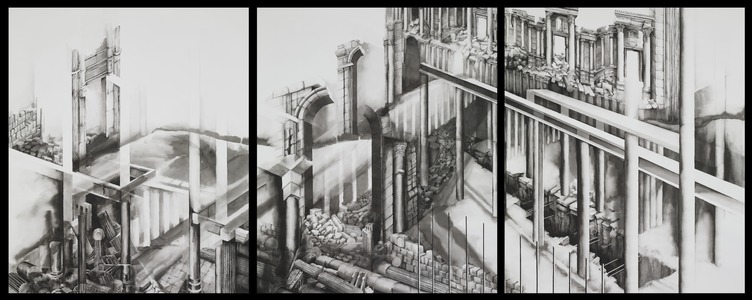

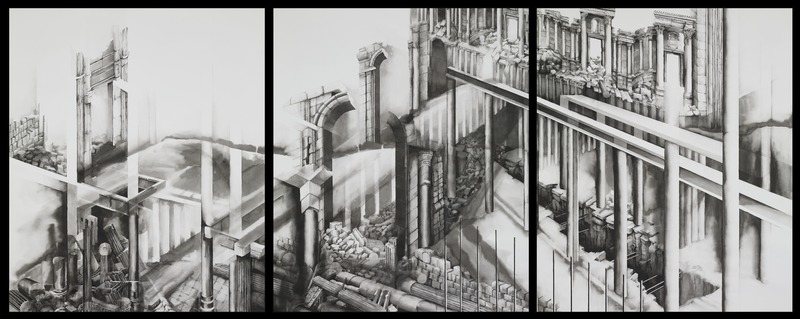

Rhodes' drawing suggests not intimacy but distance. This refutes something often said about drawing – that it is somehow more authentic, more personal or more unguarded than painting. The artists I've selected here push against this reading. In their hands, drawing instead becomes its own language, with its own limitations and possibilities, that can express particular experiences and approaches differently from other media. Take, for example, Deanna Petherbridge's large pen and ink triptych, The Destruction of Palmyra.

The Destruction of Palmyra

(triptych) 2017

Deanna Petherbridge (1939–2024)

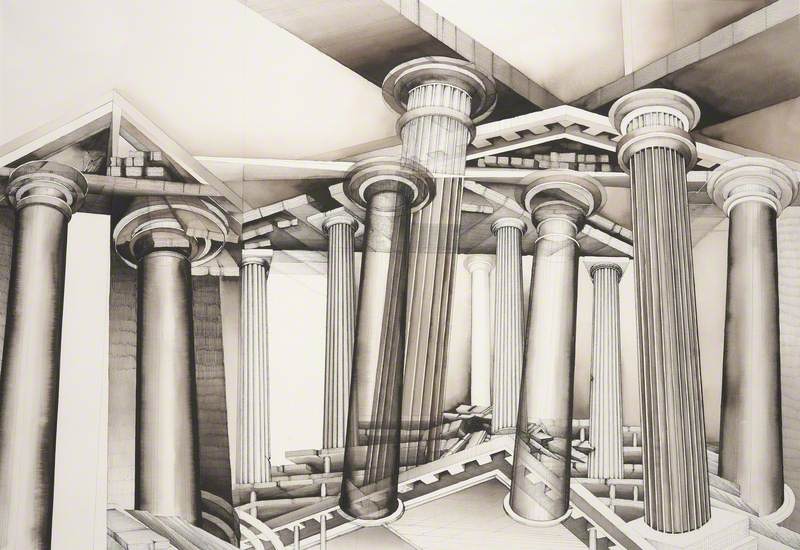

Architectural forms loom in and out of the drawing's imaginary zone. Zooming lines of perspective intersect with others, building a complex and contradictory space which consistently denies its viewers a foothold. What starts as solid melts into air. Precise lines, drawn with the clarity of an architectural drawing, disappear. The result is a bewildering mesh of vertical, column-like shapes, shot through with diagonals that trip up any attempt to map the space. These technical decisions result in an unresolved location – something evoked through an act of memory, perhaps, with all the absences and elisions that implies.

The work's title helps extend the detailed looking that the drawing invites. Petherbridge produced it based on online images of the ruined Roman temples in Syria, blown up in 2015 by ISIS/Daesh. Bringing together these contemporary images of destruction with historical photography of the temples of Bel and Baalshamin, Petherbridge built a semi-fictional, semi-researched rendering of a historical site disappearing into the past.

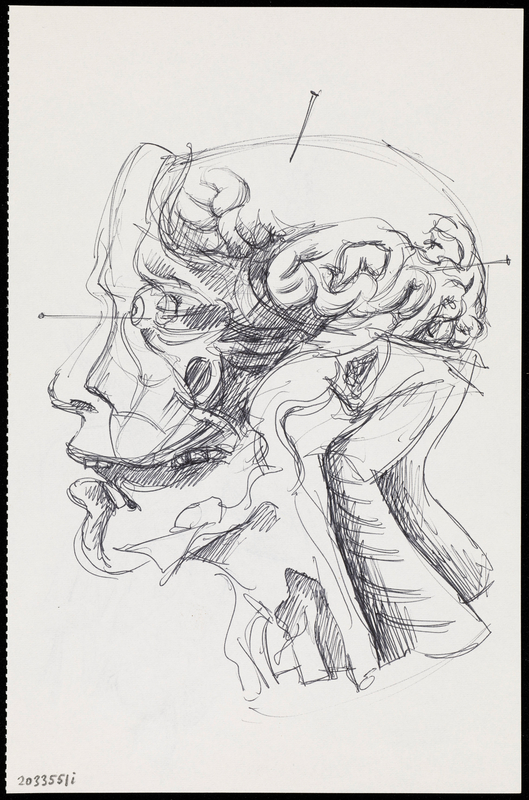

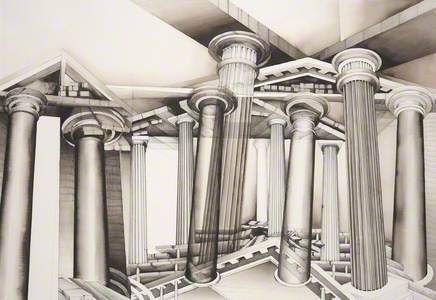

Preliminary Study for 'Broken Set of Rules'

1984

Deanna Petherbridge (1939–2024)

Petherbridge, who died in January 2024, was an accomplished writer on art as well as an artist herself. In her book The Primacy of Drawing, she discussed how, in showing the marks of its making, drawing can show 'the fully extended history and processes of its own making.' What she called 'the complicated journey of destruction, recovery, and transformation' shows how the basic actions of making a drawing can come to mean more than mere technical decisions.

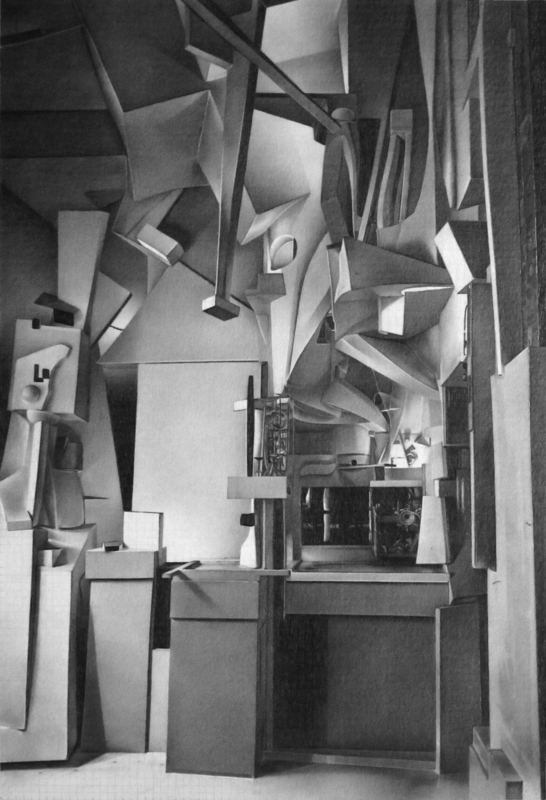

Dan Fischer's meticulous reconstruction of Kurt Schwitters' Merzbau – a kind of immersive abstracted interior, built by the artist over around 15 years in Hannover, Germany, which was destroyed in an Allied bombing raid in 1943 – brings that lost location cautiously back to life through its careful transcription of photographs of the site. The 'complicated journey' of Fischer's drawing, constructed through precise line, erasure and a range of tonal effects, does two things at once. It both allows us to see something that no longer exists and reminds us of that site's own erasure and disappearance.

Drawing's relationship to fiction is central to Charles Avery's practice, an artist who works across various media to depict locations, characters and narratives set on an imaginary island. Regardless of their material, these objects share a precision and clarity that seem to emerge from the artist's distinctively sharp graphic line, and the naturalistic appearance of fantastical things. His drawing Gallery is a good example, which initially reads as familiar.

Various figures are shown in the interior of an art gallery, doing what people do in such spaces: looking intently, discussing and debating, gossiping or ignoring the art. The gallery itself is lightly described. A geometric pattern is sufficient to suggest a tiled floor; the artworks themselves are similarly shorthand, aside from the giant rabbit – surely a nod to Jeff Koons' work – on which a child clambers. The art on view is all fictional but is close to art we might have encountered.

Avery's drawing is reminiscent of cartoons about modern art's inscrutability and pretentiousness, to the extent that you might provide it with missing captions. Make up your own for the following situations: a suited man squinting at a monochrome canvas; a man eating a sandwich as he ogles a Mondrian-like abstract painting; a couple locked in disagreement as they exit the scene.

The basis of each of these jokes is the difference between what we see and what we're told is there. Although this basic principle launched a thousand gags, it's also a fundamental concern of art in general. Avery's precisely described fiction is, like the detailed worlds of science fiction, a way of thinking about our reality by comparison. Petherbridge's description of drawing's ability to reveal the complicated history of its making provides a way to think about the fictions that surround us and determine our relationship to the world.

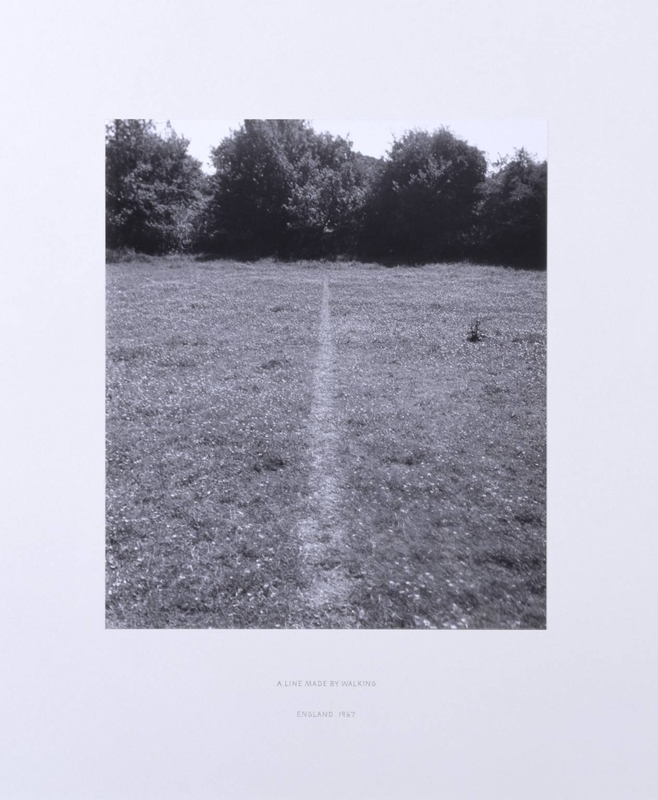

The mark on paper connects us to the world. The artist Amy Sillman writes how:

'While making a drawing, you are looking down, out, across, around, and shifting boundaries between what is inside and what is outside, because as you draw your consciousness moves from inside your body toward the outside world, but you also simultaneously drag the outside world into your hand and eventually down onto your page.'

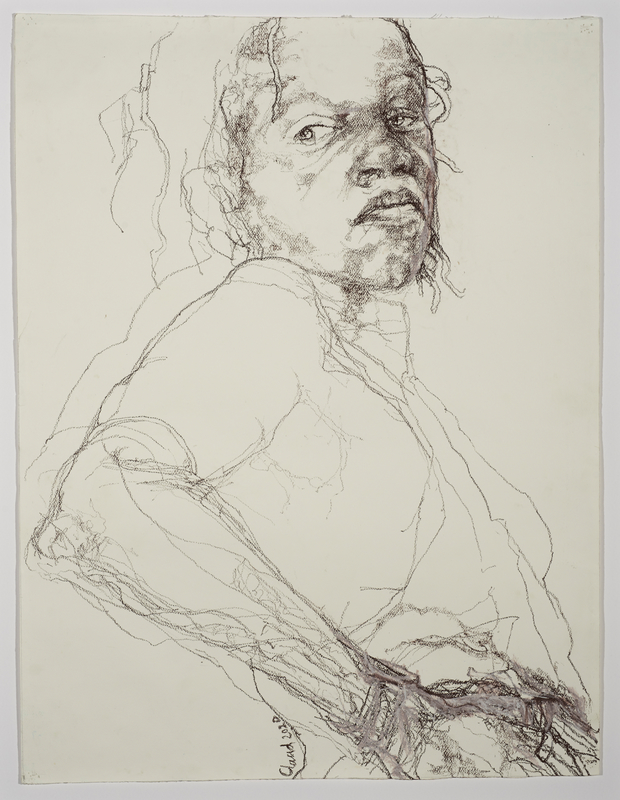

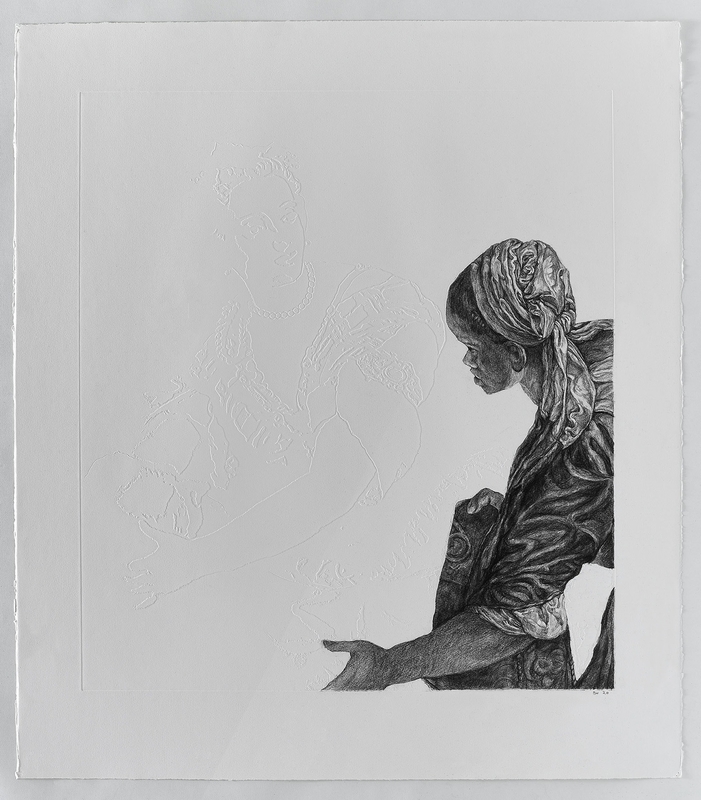

Claudette Johnson's self-portrait in oil pastel on paper feels closely related to Sillman's idea of drawing as a negotiation between ourselves and the world. Hand on hip, the artist looks down at her reflection. Repeated marks of the pastel indicate her attempts to secure the angle of her arm and position of her head: the drawing's history is laid bare. Marks gather and thicken around the artist's hand, and eyes, the twin tools of observational drawing.

Made during one of the 2020 coronavirus lockdowns, Johnson's drawing is especially charged in light of the restrictions on personal interaction in public spaces at the time. What happens when there is no 'outside world' to which the drawn mark can respond? Johnson's drawing is a kind of answer: we get a distillation of the power of drawing itself, in which the marks map a relationship between the inside world of feeling and the outside one of appearance. You are here, says the drawing, wherever that is.

Ben Street, art historian and educator

This content was funded by the Bridget Riley Foundation

Further reading

Deanna Petherbridge, The Primacy of Drawing: Histories and Theories of Practice, Yale University Press, 2010

Edouard Kopp (ed.), Drawing is Everything: Founding Gifts of the Menil Drawing Institute, Yale University Press, 2019

Amy Sillman, Amy Sillman: Faux Pas (Expanded Edition), After 8 Books, 2022