'From this evening, I must give the British people a very simple instruction. You must stay at home.'

Remembering Boris Johnson's message to the British public on the 23rd of March, 2020 is liable to evoke unpleasant memories in the minds of many of those who were living in the UK at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. With two clenched, white-knuckled fists, Johnson emphasised the importance of staying home to slow the spread of coronavirus to protect the NHS. Upon reciting an extensive list of all that was banned, Johnson followed with a beacon of hope – restrictions would be under constant review. A period of three weeks was flagged as a possible rule relaxation date. However, this proposal appears unsettlingly naive in hindsight, for the lockdown was extended considerably beyond it. Throughout 2020 and 2021 two other national lockdowns lasted months, alongside local lockdowns and a restrictive tier system. Life slowed and moved inside, repeatedly.

As lockdown life became a prolonged reality, people began passing time in new ways, or dedicated more time and attention to activities they already did. From the confines of the home, garden or balcony, friends and neighbours became sourdough bread baking enthusiasts, fitness fanatics and, increasingly, artists. With art materials and studio space restricted, drawing boomed. It was accessible to both the amateur and professional artist alike. This story focuses on the latter, exploring how artists responded to strange new times via drawing. The drawings discussed were produced in 2020 and 2021. Collectively, they demonstrate that artists used drawing for a variety of purposes: to perfect their artistry, to express both physical and mental pain, to honour what provided hope and to communicate universal pandemonium.

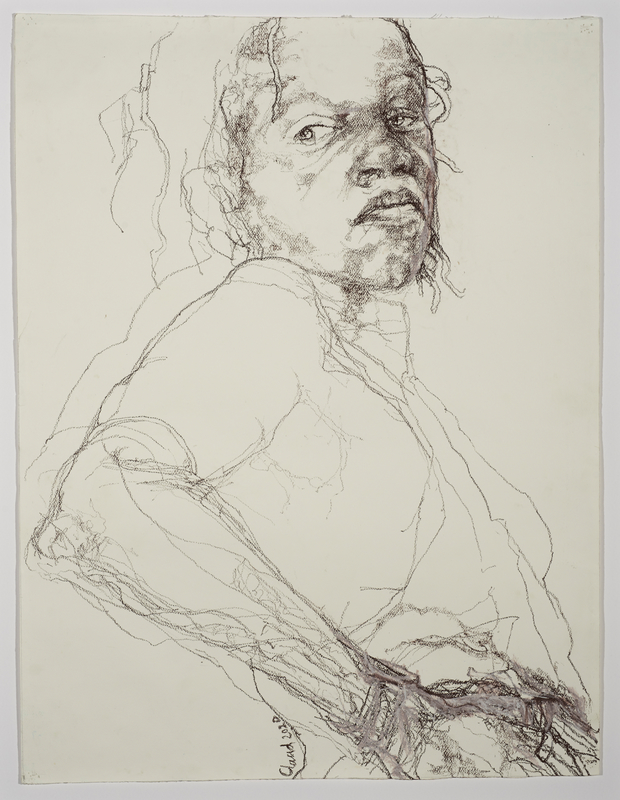

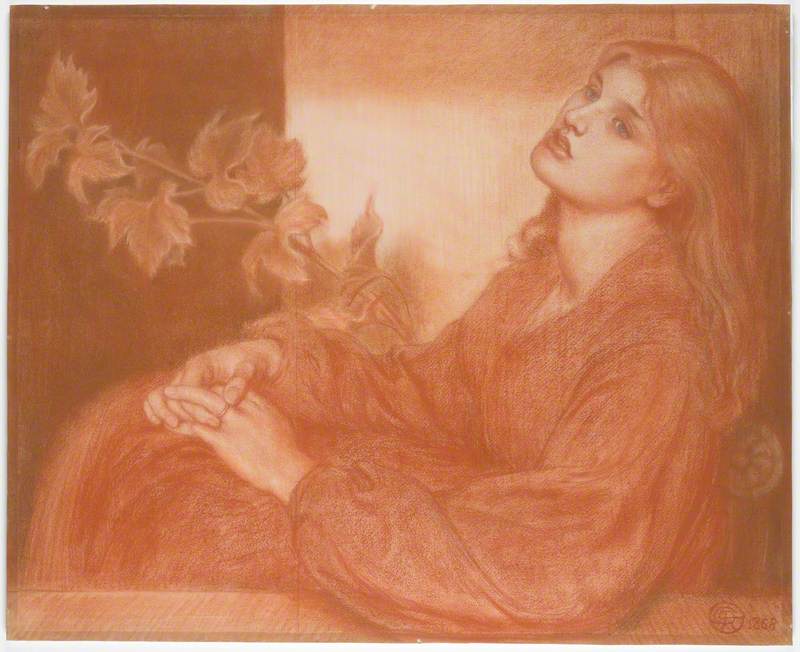

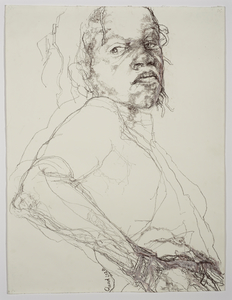

Doing Lines 1 (Lockdown) Line Journeys by Claudette Johnson is a 2020 self-portrait. Oil pastel lines shimmer across paper to reveal new views of a familiar form. Gazing intently into a mirror, Johnson, with no alternative model to hand, explores who she can be through various angles. Vibrating lines convey the presence of the artist in this moment – living, breathing and moving through time, continuing in her practice, despite being static in a physical location. The title, Doing Lines, evokes two very different things: taking cocaine and being punished (the latter relates to having to 'do lines', a written punishment at school). The first inference may imply that drawing is what Johnson needs to weather the pandemic's storm – an escape, like a drug. The second suggests that the artist feels she is back in a confined educational setting, forced to study the basics again.

When interviewed about this piece, Johnson likened her line drawings of herself to 'the equivalent of scales practice for a pianist'. As an artist, Johnson seems to find solace in the routine of these exercises. As well as being an outlet, the practice of drawing – and indeed doing her lines – provided a sense of normality: honing her craft is just a regular day at the office for Johnson. In routine there is comfort.

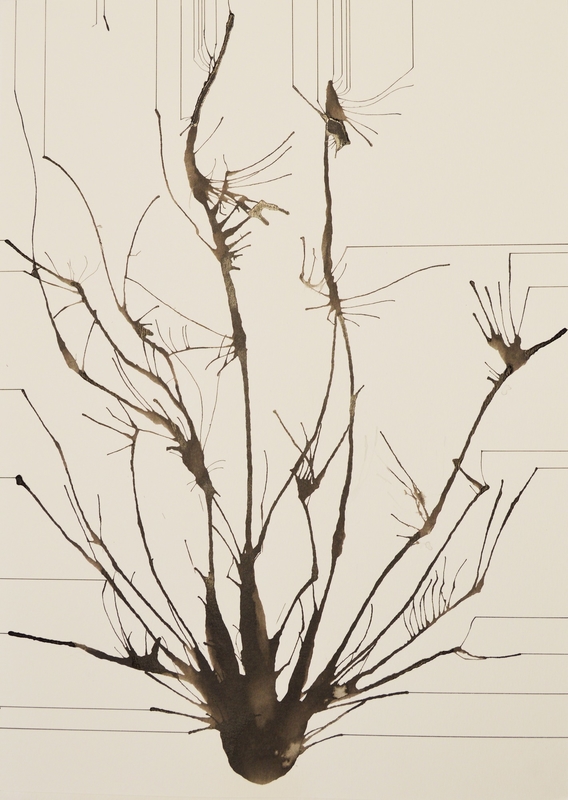

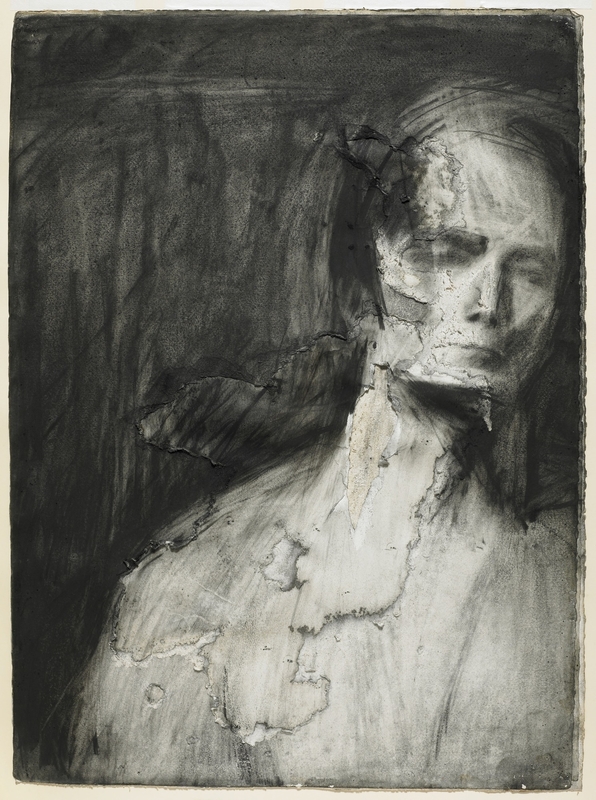

Another drawing from the lockdown era is Annie Cattrell's Holding Breath 8. This image is from a series created by the artist using her breath to blow ink over paper. Cattrell has said that this work was made in response to her experience of breathlessness after contracting COVID-19.

Visually, the immortalised breath evokes different forms. With creeping spindling arms, this structure could easily represent bronchi, germs or branches. Any of these would be apt considering the context in which the artist was working. Black and bristled bronchi, the internal structures of the lung, evoke coronavirus's impact on the body – damaging fragile structures that give life. Starbursts of sea urchin-like creatures at the extremities of the structure poetically mirror the familiar symbol of coronavirus, an angry-looking spiked ball. However, branches convey something more optimistic. They nod to trees, to growth and healing. When considered together, in order, the series depicts forms getting stronger as time passes. Individually, the images demonstrate sensations of physical limitation. Collectively, they communicate the process of healing.

Lockdown Rainbow (1 for the Government Art Collection)

2021

Graham Fagen (b.1966)

Graham Fagen's Lockdown Rainbow collection also radiates multiple feelings. In 2020, it was popular for children to place hand-drawn rainbows in windows to demonstrate hope and signal support for frontline NHS workers. Fagen used this motif as the basis for this series, but instead of purely emanating hope, these rainbows express a complex spectrum of thoughts. Although not immediately apparent, according to Fagen each rainbow is a visual representation of how an individual tooth feels in his mouth – some are fat and flat, others thin and jaggy. Using the feeling of teeth as inspiration for the rainbow's production emphasises the monotony of lockdown. There was so little to do inside, that it was commonplace to think about such bland things.

Lockdown Rainbow (2 for the Government Art Collection)

2021

Graham Fagen (b.1966)

Fagen left the practice of making each rainbow to chance, to some degree. He would set ink off in the direction he felt was right to represent a tooth, but due to the ink combining with water, each image's outcome was unpredictable. Blending this with the motif of the hopeful childlike rainbows demonstrates the complexities of Fagen's lockdown feelings. The droopiness of the ink, with colours dribbling into one another, sometimes off the page, expresses how arduous a mental undertaking lockdown was – literally draining.

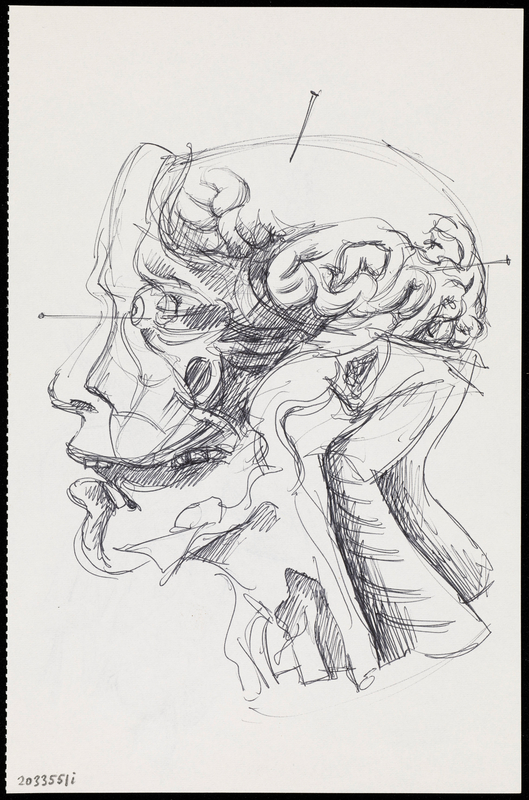

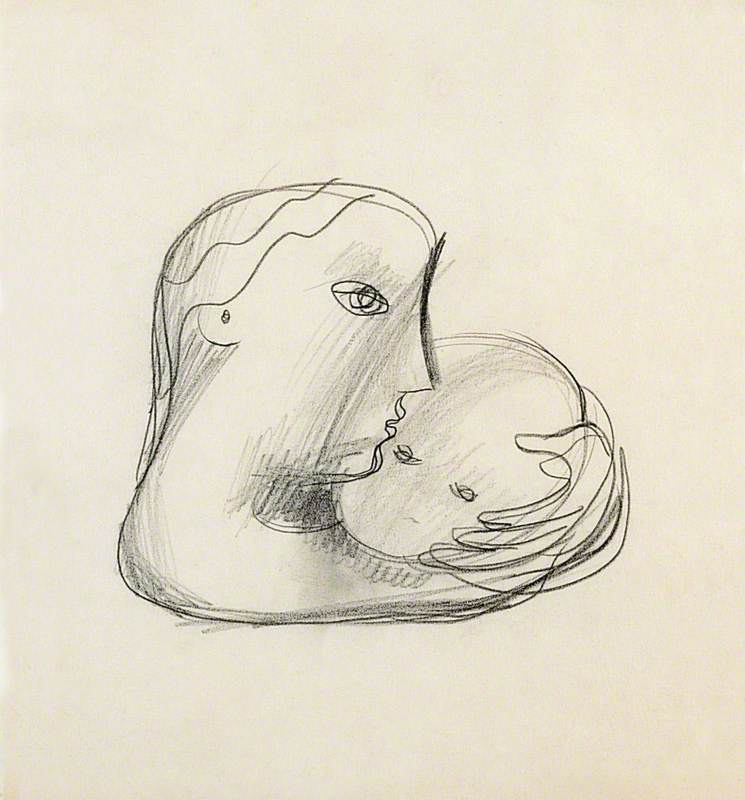

Every lockdown drawing noted so far appears visually agitated. The vibrating lines of Johnson's self, the desperately reaching spokes of Cattrell's breath and the slithering and sinking rainbows representing Fagan's feelings all articulate united nervous energy. Samantha Ellis-Fox's Still is one lockdown drawing that resists this trend.

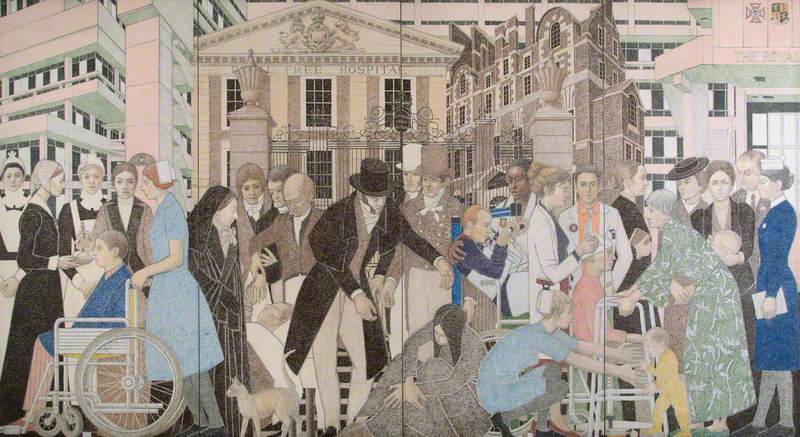

This work is serene. Here, a tired, conceivably burnt-out healthcare worker stands in majestic profile. Their eyes are closed and their head is tilted forward as if to convey they can bear no more that day. The reality may have been that this worker was not going home, but just taking a moment after tending to unprecedented horror or witnessing an untimely death. The presentation of the figure in profile evokes a pose traditionally reserved for monarchs, rulers and heroes – think coins and stamps, medals and classical reliefs. At a time when so much was uncertain and unfamiliar, people needed heroes to provide hope and illuminate a way forward. Those in power appeared to contradict themselves and provide as much doubt as clarity, so much of the UK public turned their faith to the brave frontline workers of the NHS. In this context, Ellis-Fox's image is a compassionate visual illustration of shared gratitude.

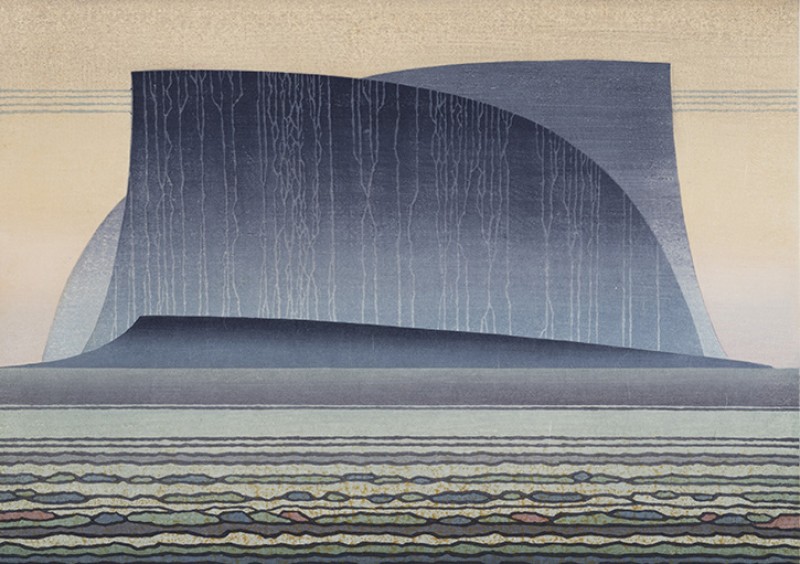

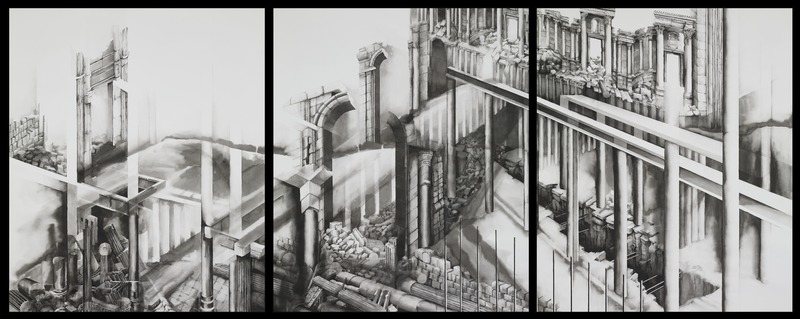

The final drawing examined here, Ro Robertson's The Island, was created in early 2020 after the artist temporarily moved to St Ives. It portrays a landscape devoid of the usual Cornwall tourists, yet it is still brimming with energy. Robertson's drawing captures the essence of the area through a swirling representation of igneous and metamorphic rocks, grassy green parkland, and sandy beaches convulsing between sea and sky. Despite the absence of visible human form, the artist imbues the landscape with a sense of turbulence. The form of this work reveals emotional depth, reflecting the internal struggles of the artist as they navigate a new and disconcertingly empty place at a particularly strange time. These are feelings that contemporary viewers could resonate with, as once familiar locations seemed abnormal without the usual cast of characters from everyday life.

In early 2020, when Robertson drew this piece, the UK was also experiencing Brexit. Although the EU Referendum was in 2016, Brexit only officially began on 31st January 2020. The nearly four-year process had been a complex untangling taking far longer than anticipated, and through it, there had been a public shift in mindset towards those leading the separation. At the same time, a 'Yes' versus 'No' vote created a divide amongst the population. At the very moment of The Island's creation, therefore, the UK was experiencing doubly uncertain times. With Brexit delayed, with multiple changes and amendments, and with lockdown evolving and extending, people were learning not to trust what they had been told the day before. Within this context, The Island appears to signify more than just pandemic pandemonium – it captures the dawn of an age of insecurity: an era that Britain, an increasingly isolated island itself, is conceivably still navigating.

Lockdown drawings explored here demonstrate that UK-based artists used and responded to this extraordinary period in our recent history in a variety of ways. Some, like Johnson, used drawing to stay on track and perfect technique. Others, like Cattrell, capitalised on the rawness of drawing to express the physical pain of the virus. Some, like Fagan, explored the mental pain of the experience by mediating on and transposing emblems that supposedly brought society together. Others, like Robertson, underlined how coronavirus was yet another thing, in an increasingly volatile time, to feel anxious about. Largely, the lockdown drawn by British artists was one crawling with feverish energy. In contrast, the one work explored here that was tranquil reveals much about who will be remembered as the heroes of the era – frontline workers like the brave fatigued figure honoured in Ellis-Fox's Still.

Fern Insh, art historian and arts engagement specialist

This content was funded by the Bridget Riley Art Foundation