In the fifth century BC, the historian Hellanicus recorded that the Persian queen Atossa wrote the world's first handwritten letter in around 500 BC.

Although writing had been used to communicate for centuries before that, her prototype caught on – until the democratisation of the telephone and the later spread of digital messaging, letter-writing remained a default channel for interpersonal communication. More than two thousand years later, Virginia Woolf would describe letter-writing as 'the humane art.'

Image credit: The National Gallery, London

Bartolomeo Bianchini perhaps about 1485-1500

Francesco Francia (c.1450–1517)

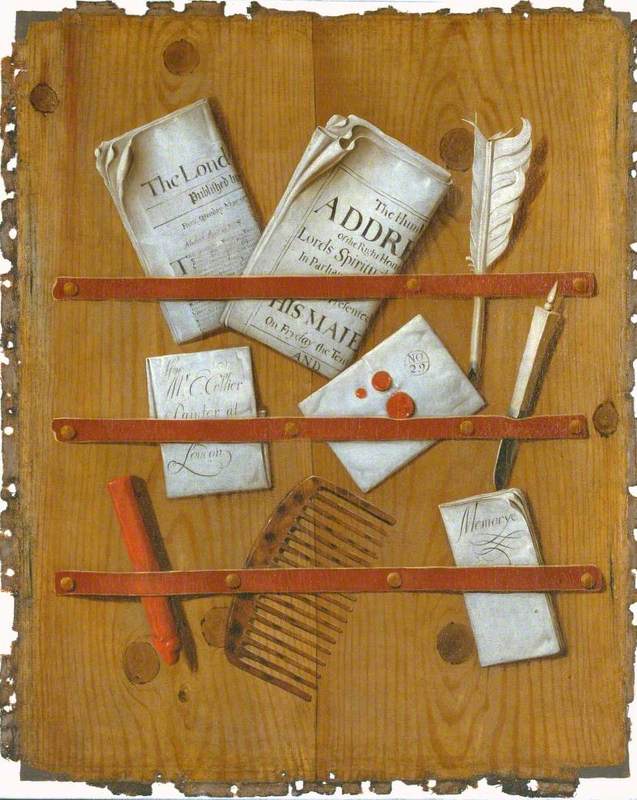

The National Gallery, LondonIt's unsurprising, then, that letters litter the history of art. They could signify a portrait sitter's identity, as in Francesco Francia's Bartolomeo Bianchini, or build romantic tension under the brushes of Gabriel Metsu and Johannes Vermeer. Edwaert Collier stuffed his trompe l'oeil pin-boards with letters, daring viewers to reach out and snoop.

Despite being a popular artistic device, letters are often overlooked as a medium for visual expression themselves. With the exception of the occasional exhibition or publication of an artist's correspondence, letters are most often treated as the subject of artworks, not art objects themselves.

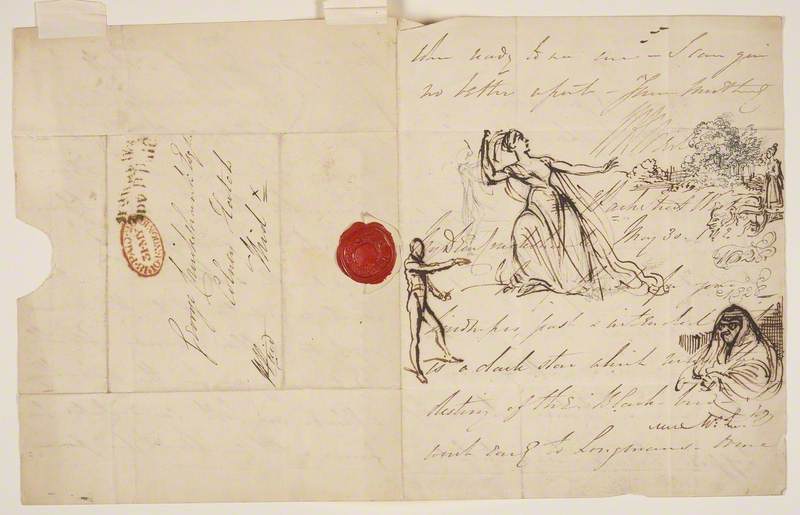

The historical ubiquity of letters does mean that they occasionally muddle their way into the art historical canon. Struck by inspiration, Guercino grabs the closest paper to hand and sketches Sisyphus.

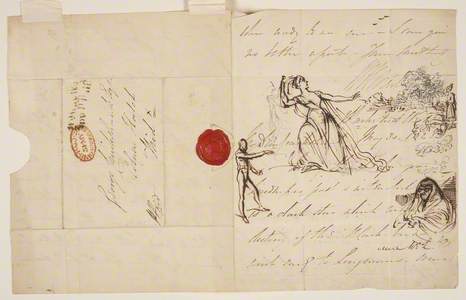

Two hundred years later, George Cruikshank does the same – here again, letters are reduced to scrap sketch paper.

Image credit: Harris Museum, Art Gallery & Library

Letter to the Artist with Three Sketches (recto) 1828

George Cruikshank (1792–1878)

Harris Museum, Art Gallery & LibraryEven Ray Johnson's 'Mail Art' movement – which used the postal service to distribute works beyond the bounds of the traditional gallery environment – focuses more on the method of distribution than on illustrated correspondence.

Illustrated letters may owe their relative obscurity to the fact that they were created for private consumption. Their primary function is to communicate, not to hang on a gallery wall or prompt academic chin-stroking. That limited audience is unique amongst art historical media; similar ephemera like sketches and cartoons may not have been considered finished works, but even they have been bought and sold at least as early as the sixteenth century, when Giorgio Vasari was compiling his Libro de' Disegni.

A peek over the shoulders of history's artistic epistolers instead reveals unvarnished work made out of necessity: for some, it was easier to draw the people, places and things they wanted to share than to write about them. Art historian Lucy D. Rosenfeld notes that Picasso 'often allowed his drawings to replace words in his notes' – filling gaps where his phonetic French fell short.

Illustrated letters are unique for their combination of the visual and the verbal. The result is what the Smithsonian Institute's Liza Kirwin described as works 'with the power to transport the reader to another place and time – to recreate the sights, sounds, attitudes, and imagination of their author.'

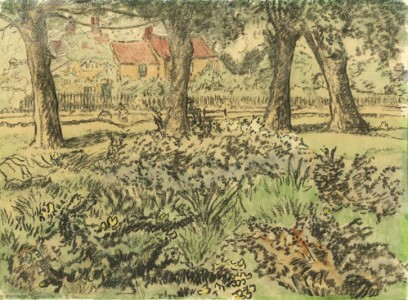

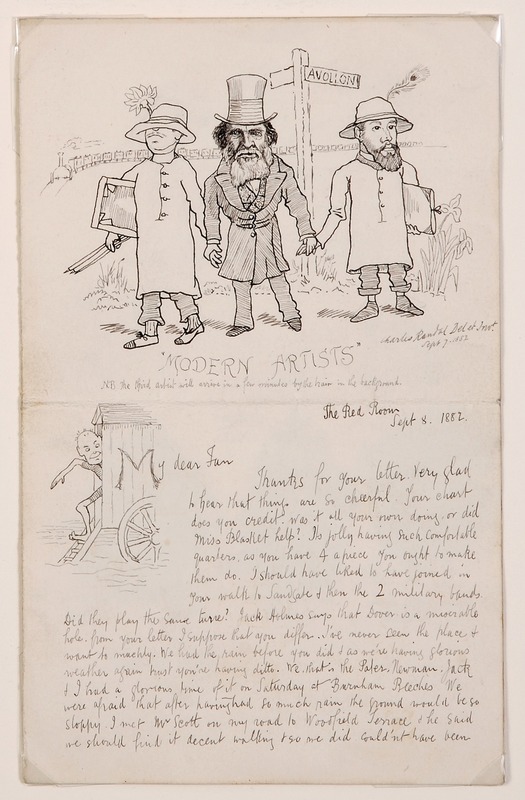

That transportive combination suits the medium to travel reports. In her book on illustrated letters from the Smithsonian archive, Kirwin dedicates an entire section to messages sent from abroad. British collections have their examples, too: Charles Randal immersed his sister in a jaunt to northern France with John Ruskin using caricatures:

Image credit: Sheffield Museums

Letter from Charles Randal to Fanny Randal; with illustration entitled 'Modern Artists' 1882

Charles Randal (1851–1928)

Sheffield MuseumsThough private, these works are not separate from their creators' aesthetic output. Each is an expression of their irresistible urge to create images. For some, illustration appears to have been a compulsion that spilled into personal correspondence.

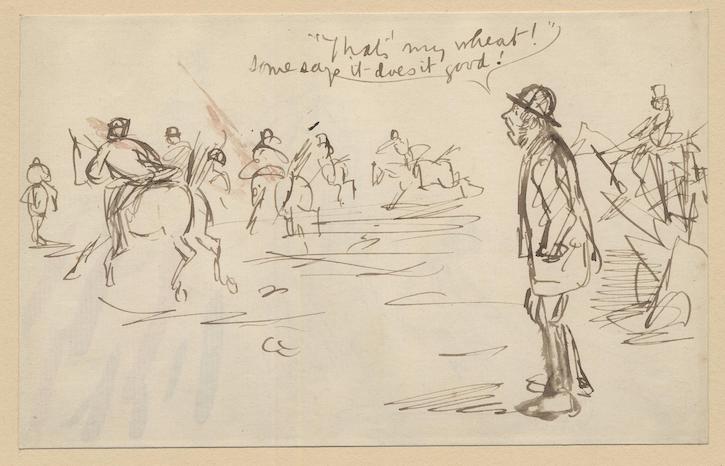

Randolph Caldecott, the late nineteenth-century titan of children's book illustration, illustrated over a hundred letters – some of which are now part of the Fitzwilliam Museum's collections. After compiling Caldecott's letters, Michael Hutchins wrote that 'Sketches tumbled from his pen as he wrote to friend or business colleague. It was as though the man couldn't stop drawing...'

Image credit: British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

'That's my Wheat! Some says it does it good!'

A farmer exclaiming as he stares at the hunt follower galloping over his fields, c.1846–1886, pen and brown ink on paper by Randolph Caldecott (1846–1886)

Edward Burne-Jones appears to have shared Caldecott's affliction, writing hundreds of illustrated letters to friends like society hostess May Gaskell and Katie Lewis (youngest daughter of Sir George Lewis). Three albums of his letters to Gaskell are now in the Ashmolean Museum's collection, while his messages to Lewis have become a unified work in their own right, published by the British Museum in 1925 as Letters to Katie.

Both collections make a surprisingly playful addition to Burne-Jones's canon. In her 1940 essay 'The Humane Art,' Virginia Woolf writes that 'all good letter writers feel the drag of the face on the other side of the page and obey it – they take as much as they give.' Instead of his usual doomed lovers and Arthurian tragedies, Burne-Jones drew society caricatures for the chronically bored Gaskell, and comical self-portraits for the precocious Lewis.

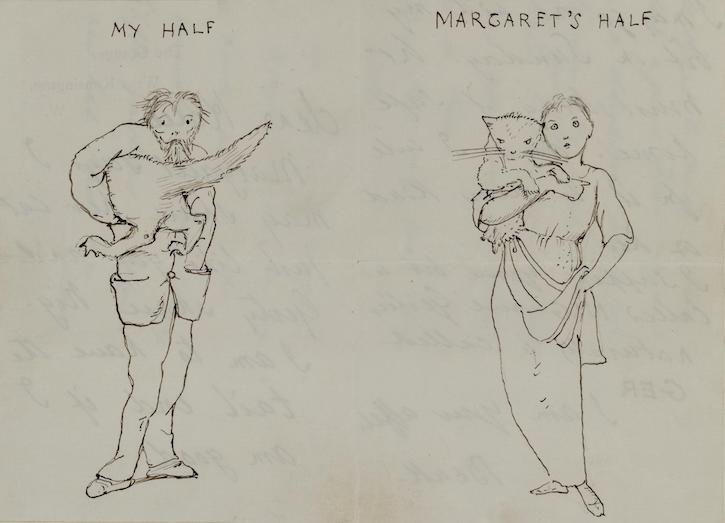

Image credit: British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Letter about sharing a cat with his daughter Margaret, from the album 'Letters to Katie'

c.1883–1889, pen and brown ink on paper by Edward Burne-Jones (1883–1898)

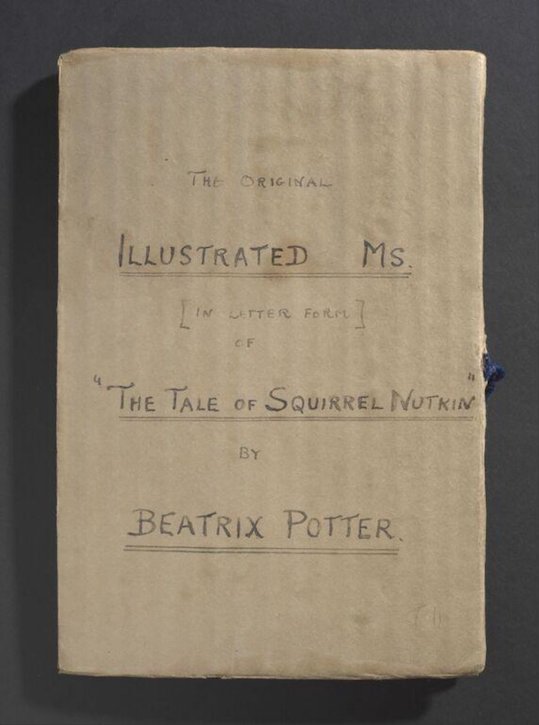

Author-illustrators like J. R. R. Tolkien and Beatrix Potter carried Burne-Jones's tradition forward into the twentieth century, illustrating letters that would eventually crystallise into published works. Tolkien's posthumous Letters from Father Christmas covers two decades of messages 'from' Santa Claus to the Tolkien children, and Potter's 'picture-letters' contain early versions of stories like The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin.

Image credit: Victoria & Albert Museum

Illustrated letter to Norah Moore, 25th September 1901

1901, pen and ink and ink on paper, paper wrappers, cotton thread by Beatrix Potter (1866–1943)

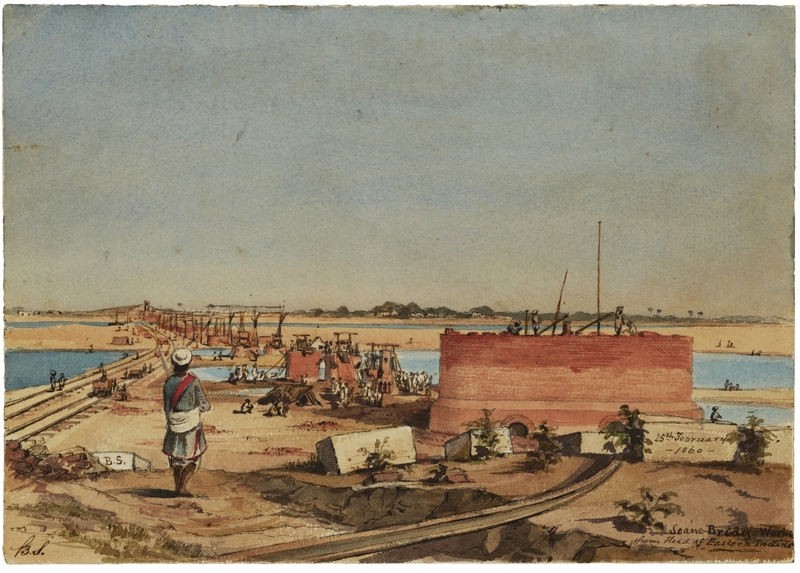

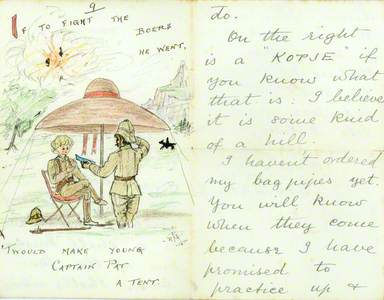

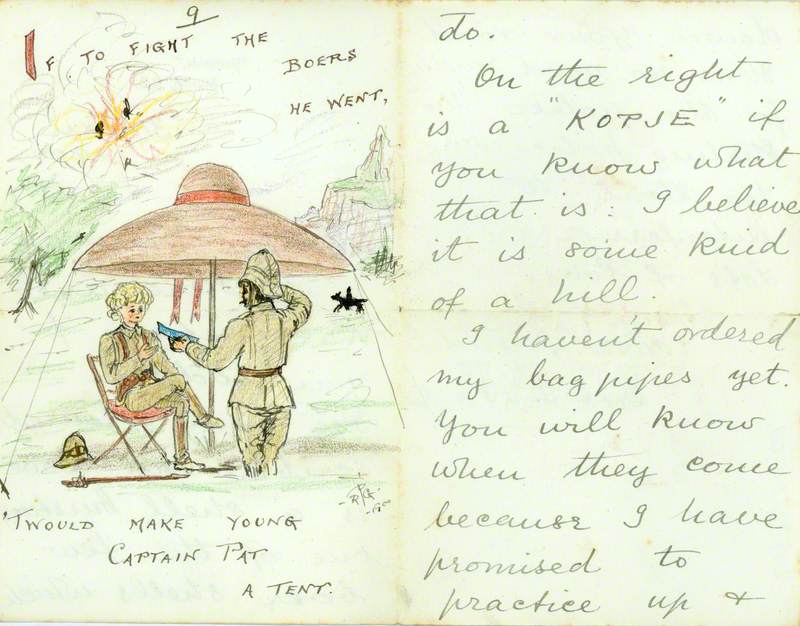

Younger recipients also inspired non-artists to take up illustration. Military figures like Dick Partridge and Sir Henry Thornhill amassed entire oeuvres in their efforts to entertain family friends and grandchildren from abroad, offering modern viewers a (sanitised) window into major historical events like the Boer War and the British occupation of India. Written correspondence created the opportunity for artistic expression and documentary illustration.

© the copyright holder. Image credit: The Stirling Smith Art Gallery & Museum

Illustrated Letter by Dick Partridge, 31st January 1900 1900

Dick Partridge

The Stirling Smith Art Gallery & MuseumType 'letter writing' into your search engine of choice, and you won't need to do much scrolling to find opinion-pieces lamenting a 'lost art.' Drawing and illustration carries on, but the illustrated letter is a medium at threat of extinction.

85 years ago, Woolf wrote that the wireless and the telephone had 'snatched away' the news and gossip that were 'the sticks and straws out of which the old letter writer made his nest.' For better or worse, the laptop and the mobile phone appear to be finishing the job.

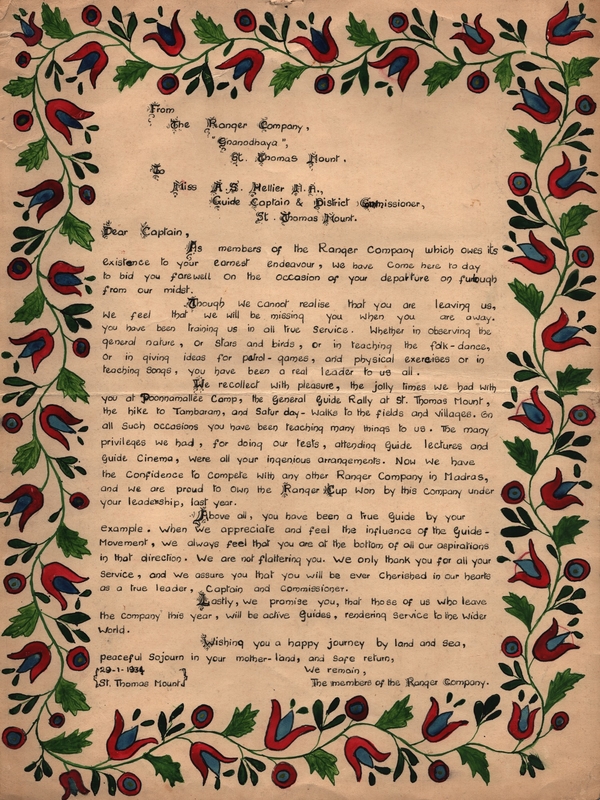

© the copyright holder. Image credit: The Oxford Centre for Methodism and Church History

Agatha Gay Hellier (1897–1980)

The Oxford Centre for Methodism and Church HistoryToday, Britons send 13 billion fewer letters a year than they did in 2004 – 13 billion fewer opportunities to put pencil (or crayon) to paper. The missives that have made their way from the post box to the museum collection recall an era in which written communication was often more intentional, and occasionally beautiful.

Alex Cohen, writer

This content was funded by the Bridget Riley Art Foundation

Further reading

Randolph Caldecott, Yours Pictorially, Frederick Warne Publishers, 1976

Liza Kirwin, More than Words, Princeton Architectural Press, 27th October 2005

Royal Mail, 'The Future of Letter Deliveries', Royal Mail Group Ltd, 2024

Jacqueline Albert Simon and Lucy D. Rosenfeld, A Century of Artists' Letters, Schiffer Publishing, 2004

J. R. R. Tolkien, Letters from Father Christmas, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 15th February 2012

Sir Henry Thornhill and Michael Baker, eds., Pictures in the Post: The Illustrated Letters of Sir Henry Thornhill to His Grandchildren, Bantam Press, 1987

Virginia Woolf, The Death of the Moth: And Other Essays, London, Hogarth, 1942