In January 1963, a flurry of letters and cards arrived at the home of the Scottish artist Adam Bruce Thomson (1885–1976). There was correspondence from friends, former colleagues and students, including the artists William Gillies, D. M. Sutherland, Phyllis Bone and William Wilson. All offered their warmest congratulations following the announcement that Thomson was to receive an OBE in the New Year Honours List. The accolade was judged to be very much deserved.

Adam Bruce Thomson painting a mural at 'The Keel Row', Leith

1941, photograph by an unknown artist. Private collection

Thomson's reaction to his OBE, however, was characteristically modest. Although he had known about the recommendation for several months, it seems he did not tell any of his artist friends about it; even his oldest companion D. M. Sutherland was taken by surprise when he read the news in the morning papers. Thomson was undoubtedly pleased to receive such recognition, but he felt no need to broadcast the achievement. He was never one for blowing his own trumpet.

'Adam Bruce Thomson: The Quiet Path', installation view, City Art Centre, 2024

Despite Thomson's self-effacing tendencies, he was in fact a highly talented artist whose versatility and dedication made him one of the most quietly impactful figures of his generation. Now a major exhibition at the City Art Centre in Edinburgh is shining a light on his contribution. 'Adam Bruce Thomson: The Quiet Path' presents over 100 artworks from public and private collections. Featuring oil paintings, watercolours, prints and drawings, as well as archival photographs, the exhibition explores Thomson's creative development, while examining his important role as a teacher, mentor and friend to other artists.

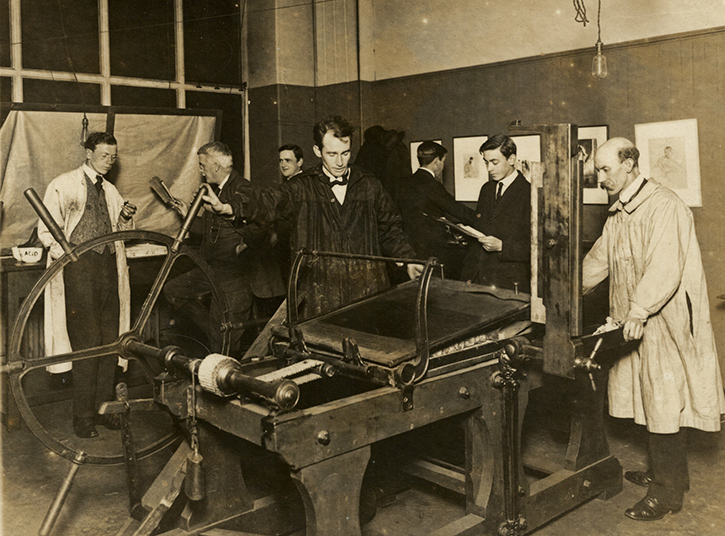

Life Class, Trustees' School of Art

c.1908, photograph by James C. H. Balmain (1853–1937). Thomson appears in the middle row, second from left, with easels behind him. His classmates include D. M. Sutherland, Eric Robertson, A. R. Sturrock and Walter B. Hislop

Thomson lived in Edinburgh all his life. Born in 1885, he undertook his artistic training in the city, initially studying architecture at the Trustees' School of Art on the Mound. As a budding architect, his accomplished draughtsmanship served him well, but over time his aspirations shifted towards the alternative discipline of fine art. A group photograph from 1908 shows him among the attendees of the life class, dressed in a painting smock and holding a palette.

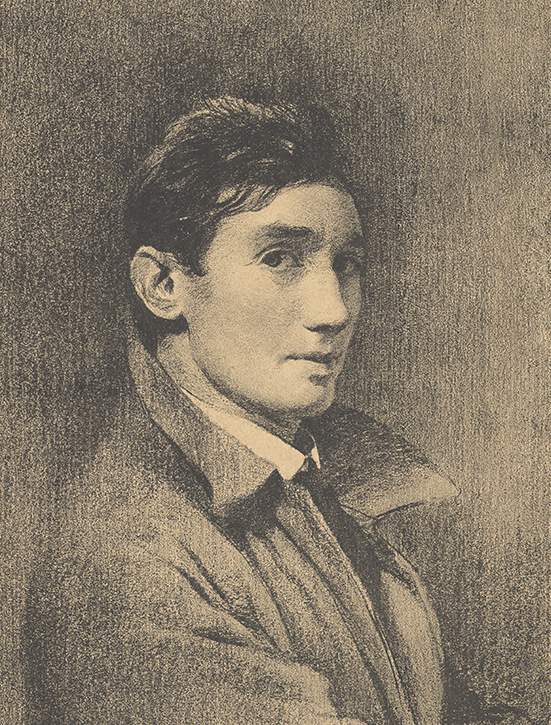

Self Portrait

c.1910–1915, lithograph on paper by Adam Bruce Thomson (1885–1976). Private collection

In late 1908, Edinburgh College of Art was established, replacing the city's nineteenth-century patchwork of disparate art schools with a single, modern institution. Existing students transferred en masse to the new college, where they benefited from state-of-the-art facilities. Thomson accordingly completed his training there, receiving an Architecture diploma in January 1909 and a Drawing & Painting diploma later that year. He was one of the very first students to graduate.

Adam Bruce Thomson with a printing press, Edinburgh College of Art

c.1909–1916, photograph by an unknown artist. Private collection

Thomson's tutors recognised his talents. Upon graduation, he was awarded two Travelling Scholarships, which funded sketching tours around England, France and Spain. Travel broadened his creative horizons and reinforced his commitment to becoming a professional artist. When he returned to Scotland in the autumn of 1910, he accepted a teaching post at Edinburgh College of Art.

Thomson taught at the College for 40 years, instructing and inspiring successive cohorts of students. He led classes in etching, elementary drawing, still life and colour theory. William Gillies, William Wilson, Anne Redpath, Robin Philipson, Wilhelmina Barns-Graham and Elizabeth Blackadder are just a few of those who trained under him. Although he had a reputation for exacting standards, he was ever-supportive of young talent. Staff and students alike knew him affectionately as 'Adam B.'.

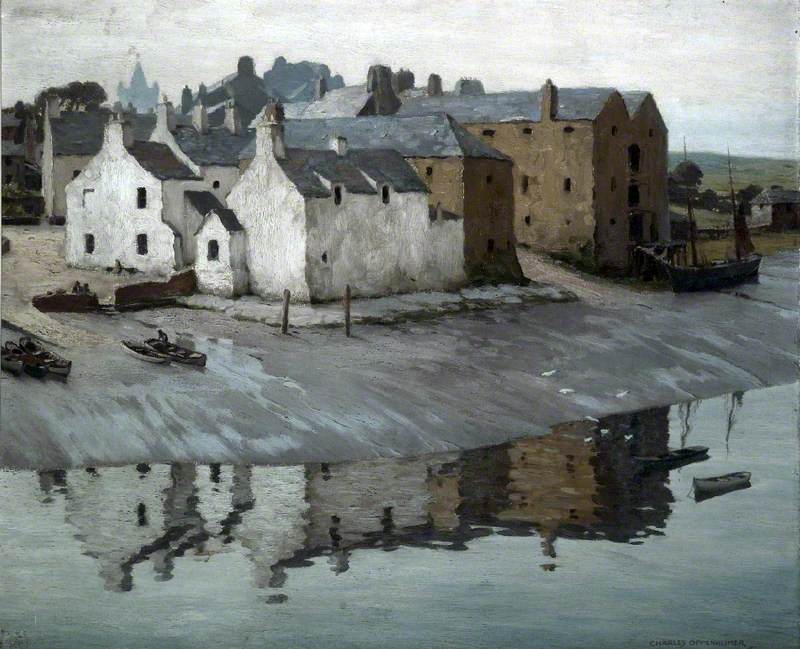

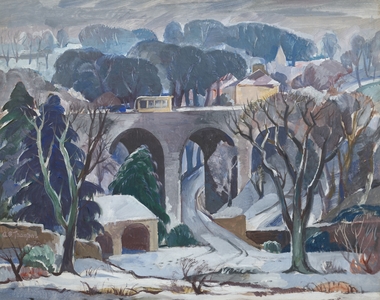

Edinburgh – Canal Basin

c.1913

Adam Bruce Thomson (1885–1976)

Like most of his colleagues at Edinburgh College of Art, Thomson balanced teaching duties with the development of his own artistic practice. His initial focus was on printmaking, honing his skills in etching and lithography. He had access to high-quality printmaking equipment and expertise at the College, and sought technical advice from Frank Morely Fletcher and Ernest S. Lumsden. Edinburgh – Canal Basin demonstrates his growing confidence in the field.

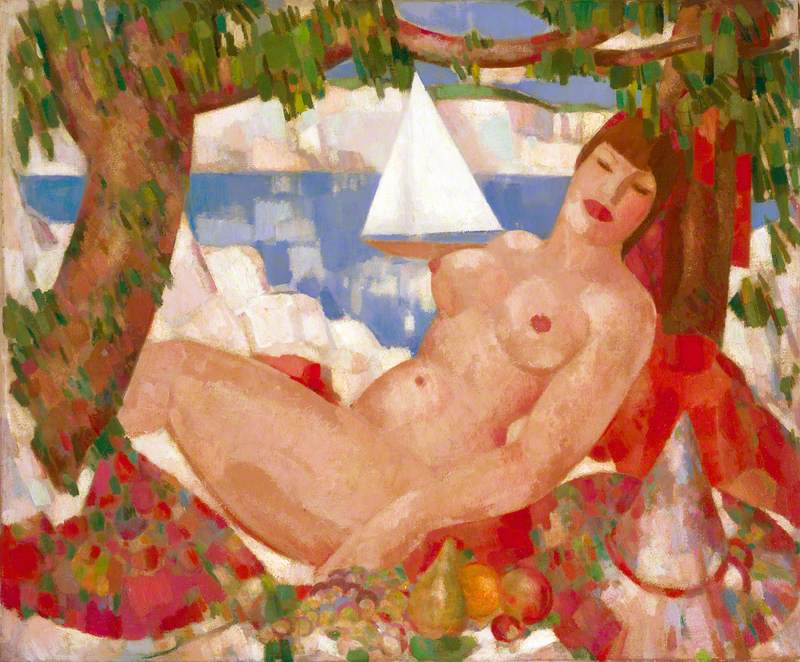

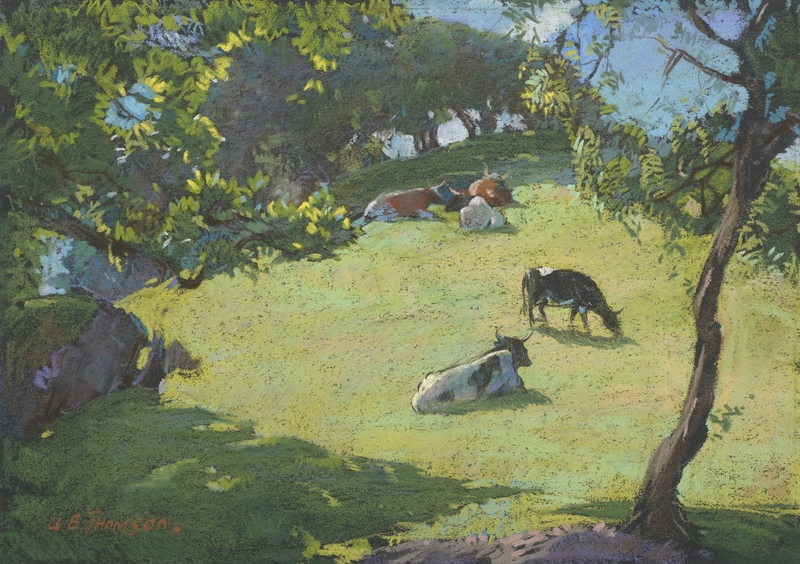

Trees and Cattle, Colvend

1920s

Adam Bruce Thomson (1885–1976)

Thomson was also interested in rural landscapes, and made regular trips to Dumfries and Galloway as well as the north-west Highlands. He often captured the Scottish countryside in pastels, producing small-scale drawings in vivid, jewel-like hues. His representations of dappled sunlight and shadow are particularly effective.

Royal Engineers Building a Suspension Bridge

c.1916, ink & wash on paper by Adam Bruce Thomson (1885–1976). Private collection

During the First World War, Thomson served with the Royal Engineers, and saw action in France and Belgium. He lost a number of friends in the conflict, including Walter B. Hislop, whom he had known since his student days. Towards the end of the war, Thomson married Hislop's sister Jessie. The couple subsequently set up home in the Marchmont area of Edinburgh.

Adam Bruce Thomson and Jessie Thomson, Edinburgh

c.1970s, photograph by J. Kinghorn. Private collection

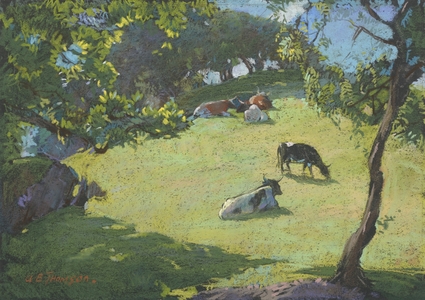

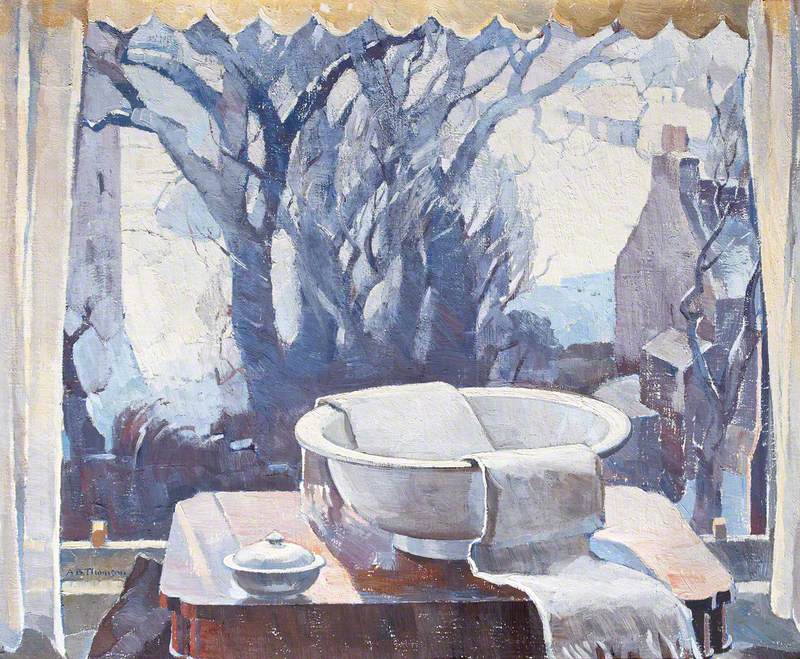

From My Bedroom Window

1923–1939

Adam Bruce Thomson (1885–1976)

The return to civilian life saw Thomson embrace domestic subjects in his art. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s he experimented with still life and interior themes, painting complex arrangements of household objects that subtly blur the boundaries of genre. From My Bedroom Window, for example, juxtaposes a restrained still life composition against an expansive landscape backdrop, playfully framed by a set of curtains. The canvas was exhibited at the Royal Scottish Academy in 1929, and later purchased for the nation by the Scottish Modern Arts Association.

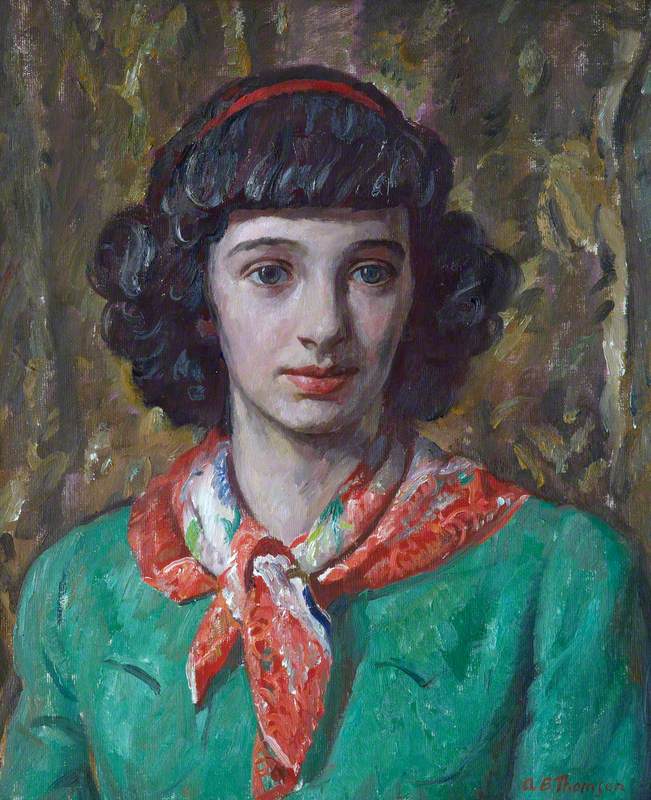

The artist's young family also provided inspiration. Over the years, Thomson made scores of drawings of his wife Jessie and their three children: Ronald, Margaret and Mary. As the children matured, they became subjects for large-scale oil paintings. Mary, in particular, modelled frequently for her father, resulting in some of his most sensitive portraits.

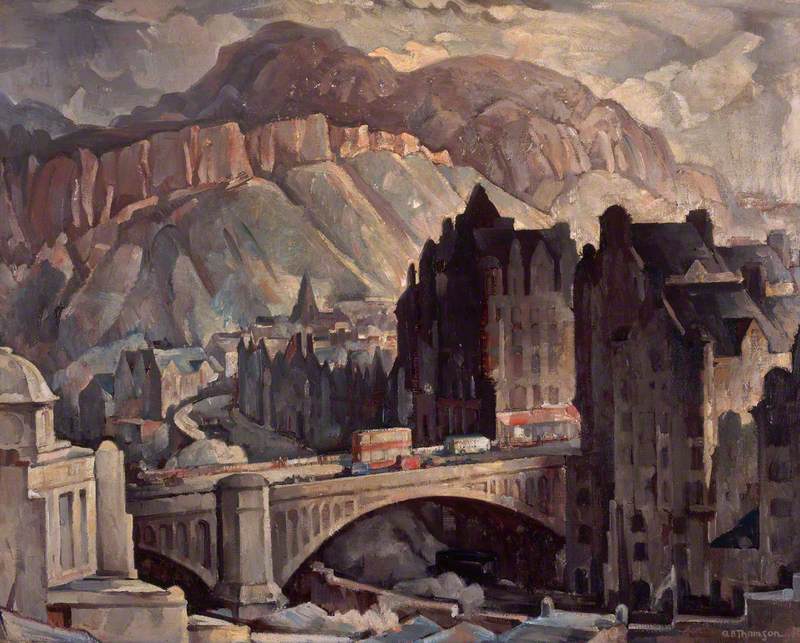

North Bridge and Salisbury Crags, Edinburgh, from the North West

1932–1934

Adam Bruce Thomson (1885–1976)

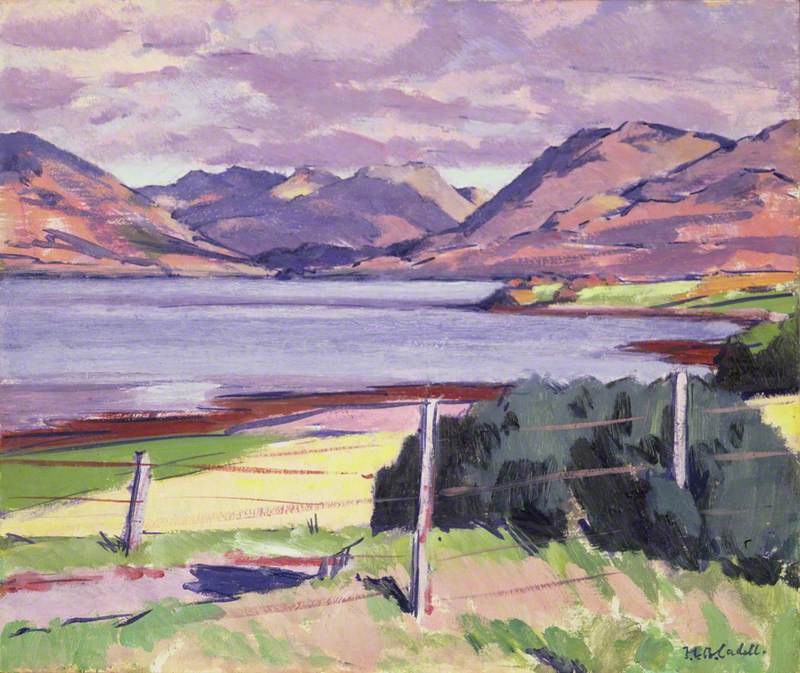

Living and working in Edinburgh, Thomson made good use of the city's scenic vistas. In the 1930s he developed a series of oil paintings which emphasised the dramatic architecture of the Old Town. These monumental canvases combine the formal aesthetics of Cubism with an expressive handling of light and shade, interpreting Edinburgh's historic heart through a distinctly Modernist lens. Thomson's contemporaries were impressed. One of the largest paintings, North Bridge and Salisbury Crags, Edinburgh, from the North West, was bought by the Society of Scottish Artists and presented to the city as a civic gift.

Thomson's profile grew steadily during the 1930s and 1940s. In 1936 he became President of the Society of Scottish Artists. The following year he was elected as an Associate of the Royal Scottish Academy, progressing to the rank of Academician in 1946. Regular participation in group exhibitions helped him to secure prestigious commissions, including a decorative panel for the headquarters of the Edinburgh Savings Bank and two formal portraits of Professor Norman Kemp Smith, Chair of Logic and Metaphysics at the University of Edinburgh.

Thomson retired from teaching at Edinburgh College of Art in June 1950. Afterwards, he maintained close ties with the College, joining its Board of Management and sharing his expertise as an examiner. He also continued to serve artist-led organisations like the Royal Scottish Academy and Royal Scottish Society of Painters in Watercolour. His dedication was recognised and appreciated by his peers.

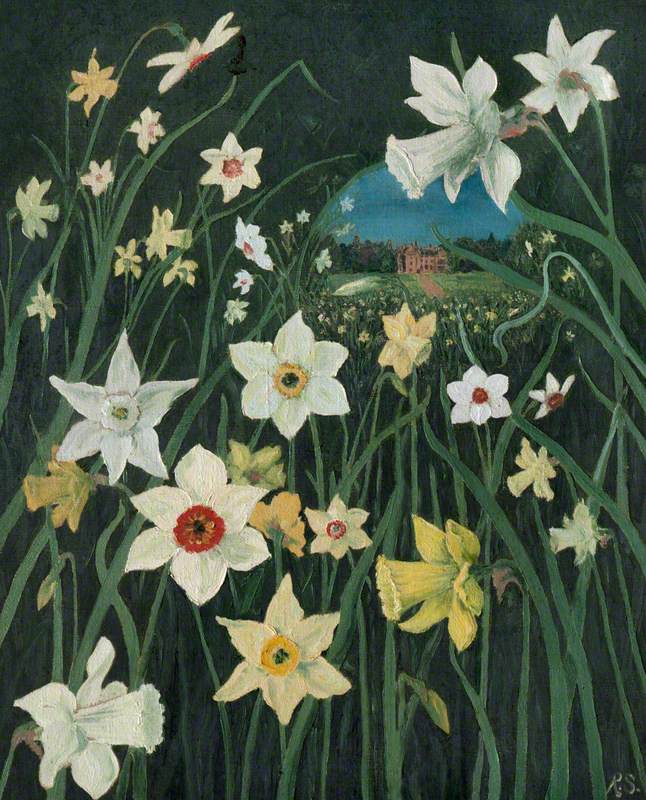

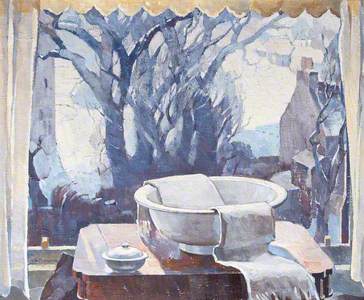

Palm, Pampas Grass and Duncraig

1965–1967

Adam Bruce Thomson (1885–1976)

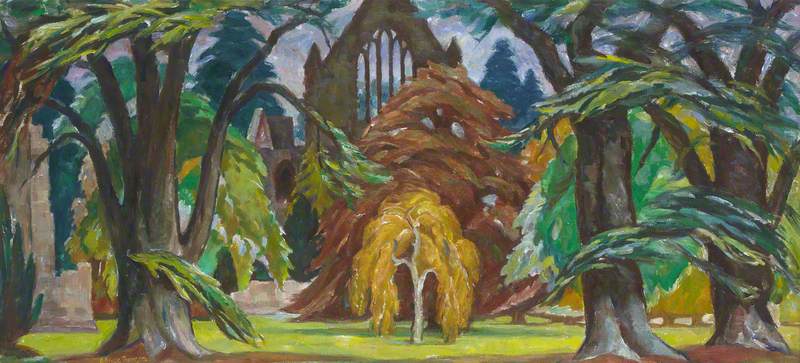

Retirement afforded Thomson more leisure time to spend in the Scottish countryside. Wester Ross in the north-west Highlands, a region known for its spectacular mountains and sea lochs, became a favourite painting destination. He was also drawn to the wooded landscapes and historic ruins of the Scottish Borders. Surviving correspondence with fellow artists describes many of his trips to these locations.

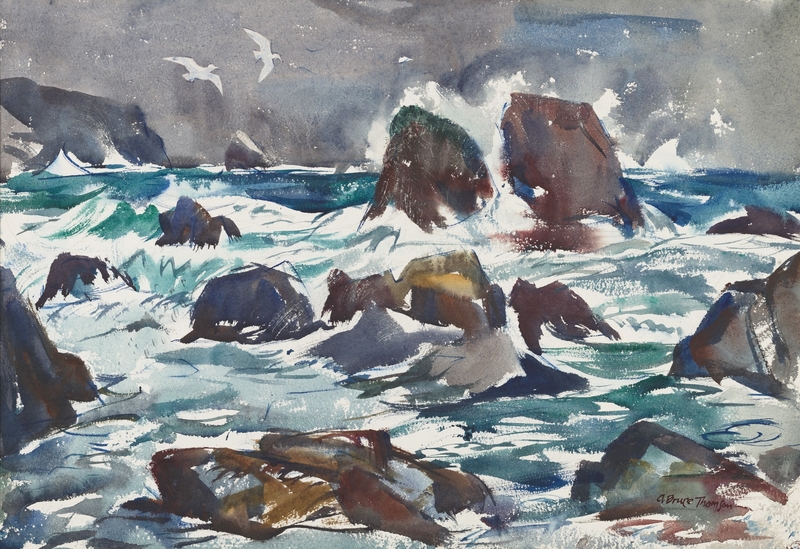

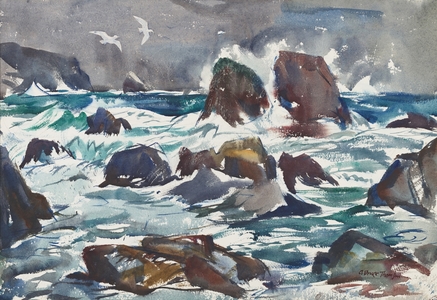

Painting in watercolours was another significant element of Thomson's mature practice. Compared to oils, he found the spontaneity of watercolour techniques profoundly liberating. Working outdoors, in direct contact with nature, his style became more fluid, whilst always retaining its innate sense of compositional structure.

Thomson carried on painting and exhibiting into his early 90s. By this time, he was living in the Blackford area of Edinburgh, which offered panoramic views of Arthur's Seat. He studied this local landmark at length, depicting it in all weathers and changing seasons. It remained a potent subject for the artist, featuring prominently throughout his final years.

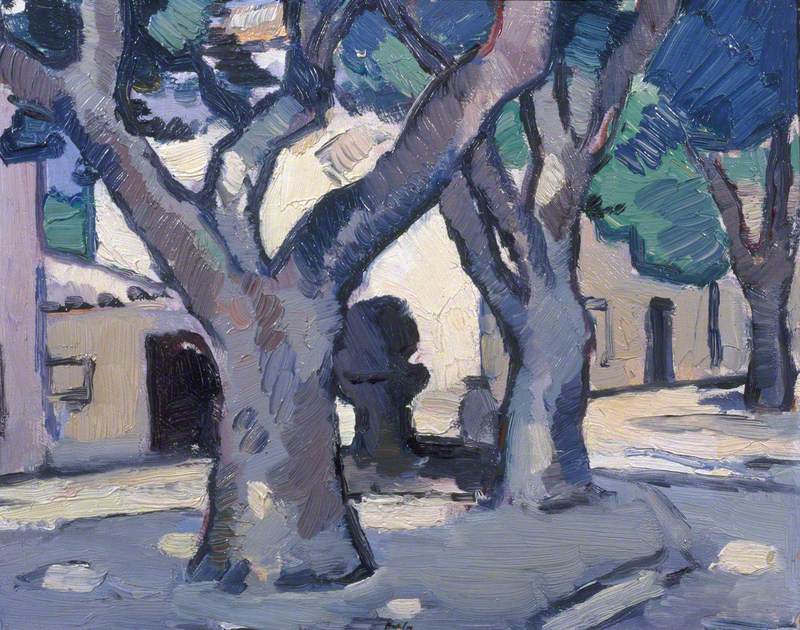

The Road to Ben Cruachan

c.1932, oil on canvas by Adam Bruce Thomson (1885–1976). Private collection

Thomson passed away in December 1976, leaving a substantial oeuvre of paintings, drawings and prints. The majority of his artworks are held in private collections and rarely seen in public. As such, his contribution to twentieth-century Scottish art is not immediately apparent. Thomson's unassuming personality and reluctance to self-promote has also had a marginalising effect; at present, his name is little-known compared with many contemporaries. Yet his legacy as an artist and teacher is nonetheless enduring, both in terms of the quality of his output and his long-term influence on others. While Thomson's footsteps may have been quiet, they certainly left their mark.

Helen Scott, Curator of Fine Art, City Art Centre

'Adam Bruce Thomson: The Quiet Path' continues at the City Art Centre in Edinburgh until 6th October 2024. Helen Scott's accompanying book is published by Samson & Company