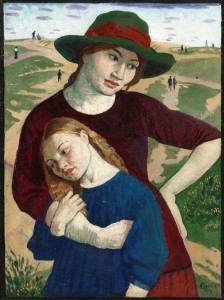

Painted on the eve of the First World War, the above double portrait by John Currie (1883–1914) contains traces of both murder and mystery. The older of the two figures depicted, as previously discussed on Art UK, is Dolly Henry, portrayed in a touching embrace with a child on Hampstead Heath. Henry was later fatally shot by the artist.

The identity of the young girl was described as 'unknown' when the work sold at Bonhams in 2018 for £31,250.

But that mystery is now solved thanks to Peter Eaton, an 85-year-old retired IT manager from North Yorkshire. 'The girl,' he said, 'is my mother Helen who was then about 11. Dolly was her favourite sister and she used to stay with her and Currie in London.'

Helen Eaton, sister of Dolly Henry

Peter's version of events which led to Dolly's death is rather different from that told by Currie's friends after the artist turned the gun on himself.

According to most of their accounts, Dolly was an empty-headed flirt who drove the talented Currie to distraction. Finally losing control after hearing that Dolly had posed for lewd photographs, he stormed into her London lodgings and shot her several times before shooting himself.

Their three-year affair began when Dolly was working as a shop assistant in a London store. She was 17 and Currie, who had abandoned his wife and son, ten years older.

The scandal of the murder and Currie's suicide was seldom discussed by Dolly's family but it haunted Peter's mother Helen in later life when she tried to make sense of her sister's death.

According to Peter, Helen believed that Dolly wanted to leave Currie after meeting another man who, unlike her artist lover, was wealthy, respectable and unmarried. So what of Dolly's background?

Before she moved to London she lived with her parents Kate and Thomas in the family home in Colchester. Thomas was a successful fur and textile importer until his career was cut short by a stroke. Dolly, who was one of seven children, left school at 14.

When Peter's mother Helen visited Dolly in Hampstead she was sketched by both Currie and his close friend Mark Gertler. 'They were kind to her. She told me they patted her on the head and gave her sweeties.'

But Currie became possessive with violent mood swings and began to think of Dolly as a witch.

Dolly tried to escape Currie's erratic behaviour. On one occasion he is said to have held a razor to her throat and on another threatened to push her off a cliff.

She eventually took refuge in Cornwall where she sought work as an artist's model. Laura Knight (1877–1970) wrote in her autobiography of returning home one day to find Dolly waiting in her garden. 'She looked a sunflower herself among the sunflowers. I engaged her at once.'

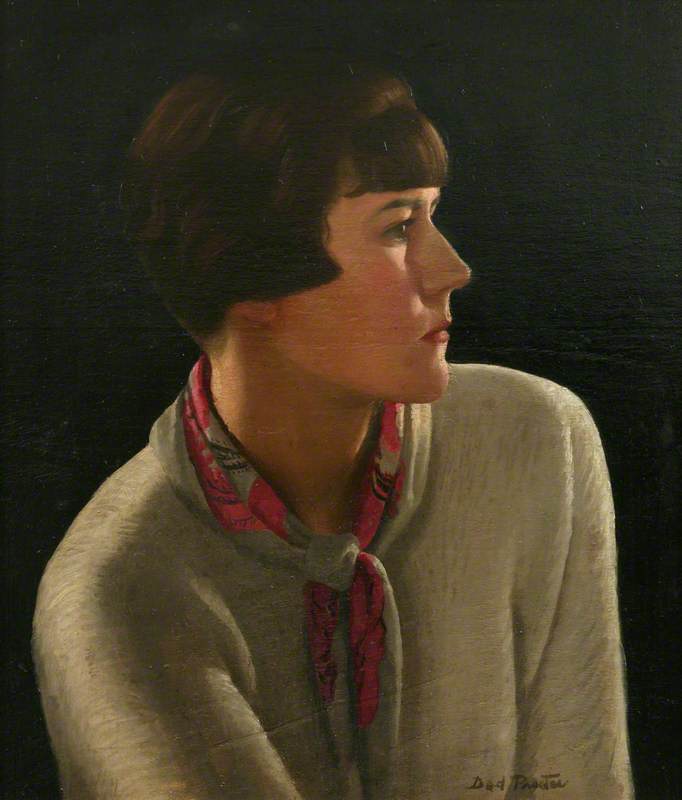

Knight was then part of an artistic community which included Stanhope Forbes, Ernest and Dod Procter and Lamorna Birch. She and her painter husband Harold were based in Cornwall between 1907 and 1919. It was one of the most fertile periods of her long career. 'An ebullient vitality made me want to paint the whole world and say how glorious it was to be young and strong.'

Because of the threat of invasion, she was prohibited from painting the Cornish coastline and so concentrated on portraiture.

Although neither are in public collections, in recent years two Laura Knight portraits of Dolly have been sold at auction – at Christie's and at Sotheby's. You can see in them a very different character than the one portrayed by Currie – the contrast between his 1913 Witch and Knight's 1914 portraits of Dolly could hardly be greater.

When Dolly spoke of being trapped in an abusive relationship Laura and Harold didn't take her seriously:

'While we were working she told me of her terror of a painter called Currie. "I know he is going to try to kill me again; he has tried to do so before," she said, and I thought she was talking sensational nonsense.'

But when the couple began to receive threatening letters from Currie demanding to know Dolly's whereabouts they realised her fears were well-founded. A few weeks later they read a newspaper account of Dolly's murder.

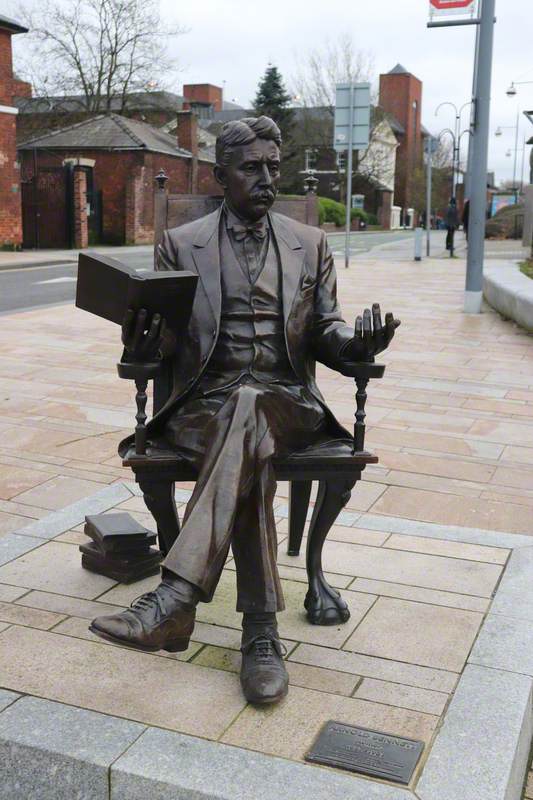

James Trollope, author and columnist