In our time of obsession with appearance, the way we perceive the human body's journey through life can sometimes lean towards a sense of impending doom rather than celebration. David Shrigley's bright and distinctive artwork, full of ballooned proportions and anamorphic states, is a tonic for those feelings of darkness. It's a kitchen magnet philosophy for the arty set. It's Proust for telly lovers.

In some ways, the work of David Shrigley does what we all do when we don't want to think about looks, judgement or mortality. We fill our evenings, weekends and holidays with sunshine, colour and delicious things. We shop, we satiate, we frame. But of course, we end up thinking about those initial concerns all the same.

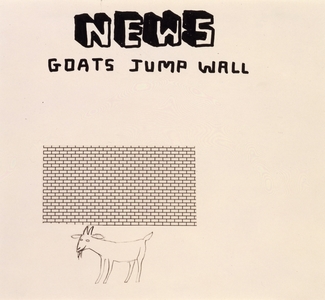

The reasons why Shrigley is so enormously prolific and popular are sort of at odds with one another: there's a sincerity to his approach that is altogether humbling, but then, right as you're letting your guard down, you find yourself giggling at the silly anecdote he writes or the bulbous shape of his subject. His work brings humility and levity hand in hand.

To make work that is so instantaneously distinct cannot be learned. Shrigley was born in Cheshire in 1968. He enrolled at Leicester Polytechnic on a design foundation course before moving on to an Environmental Art degree at the Glasgow School of Art. He remained in the Scottish city for 27 years, working as an assistant at an art museum for many years before he started to forge his own path with his unique style.

In 1995, already adored by scenesters and peers, the artist scored his first Frieze cover. The moment catapulted directly into the international art world, with the following year seeing Shrigley's work on show in Copenhagen, New York and Amsterdam.

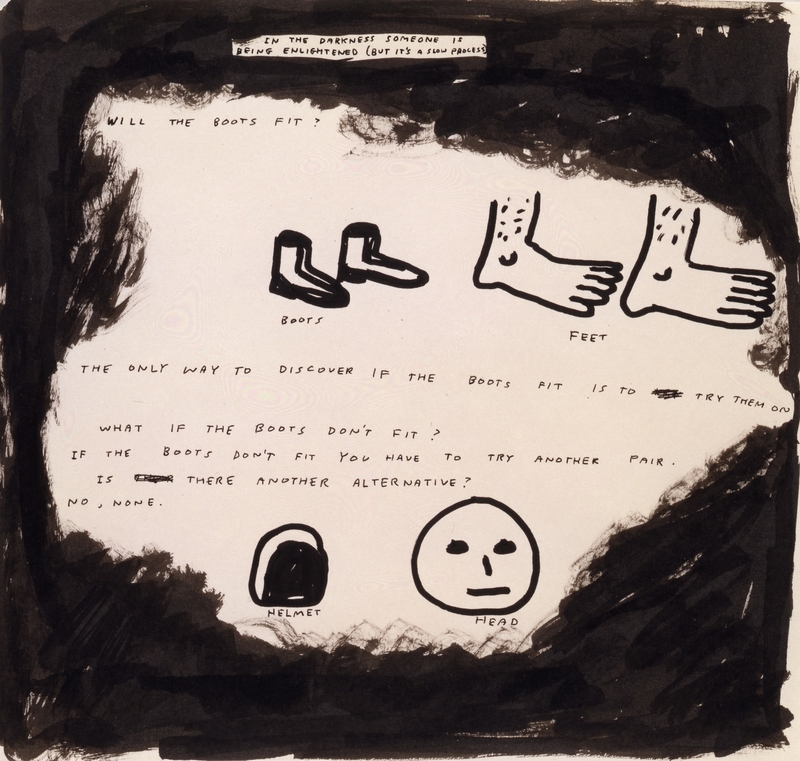

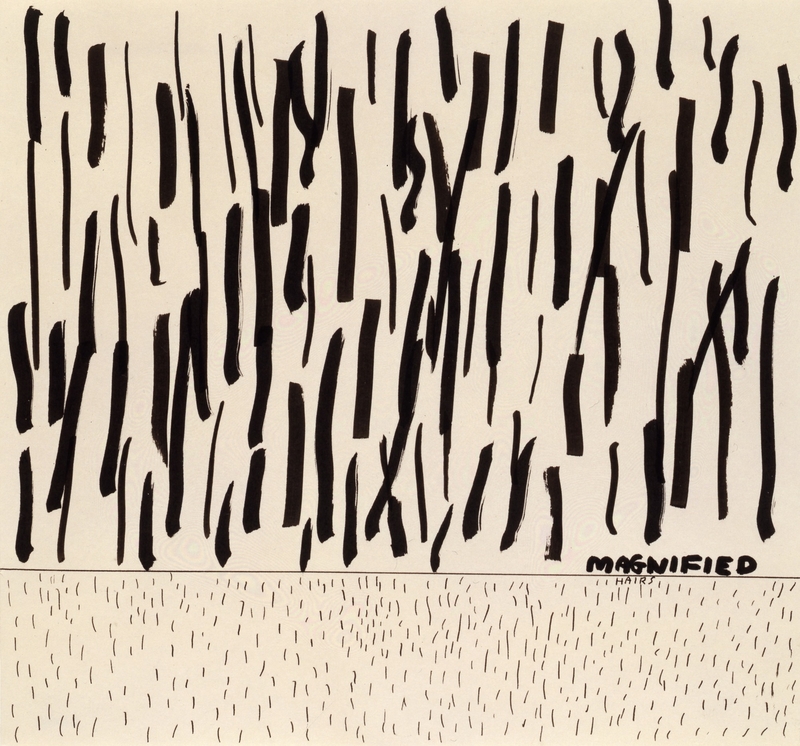

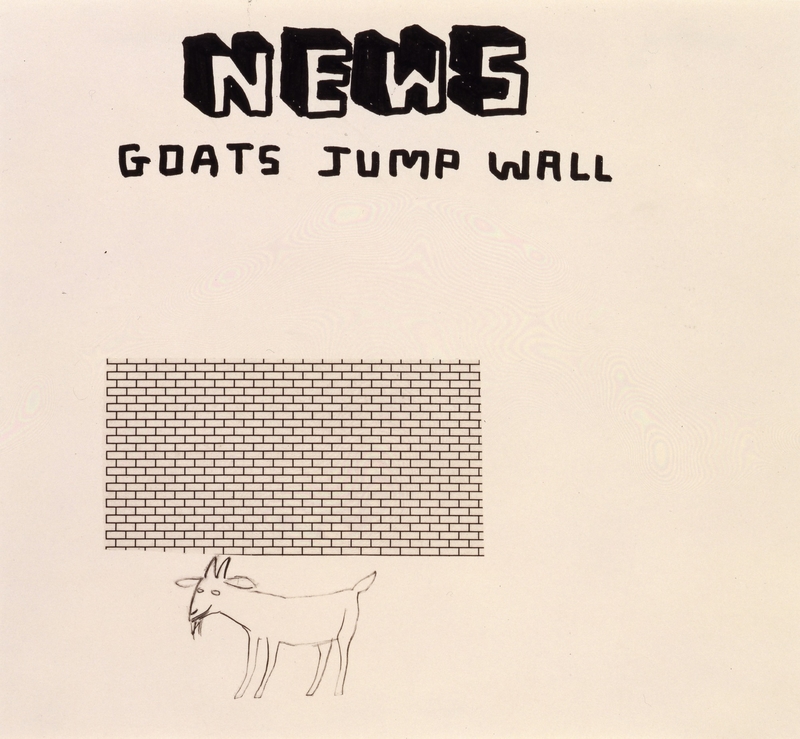

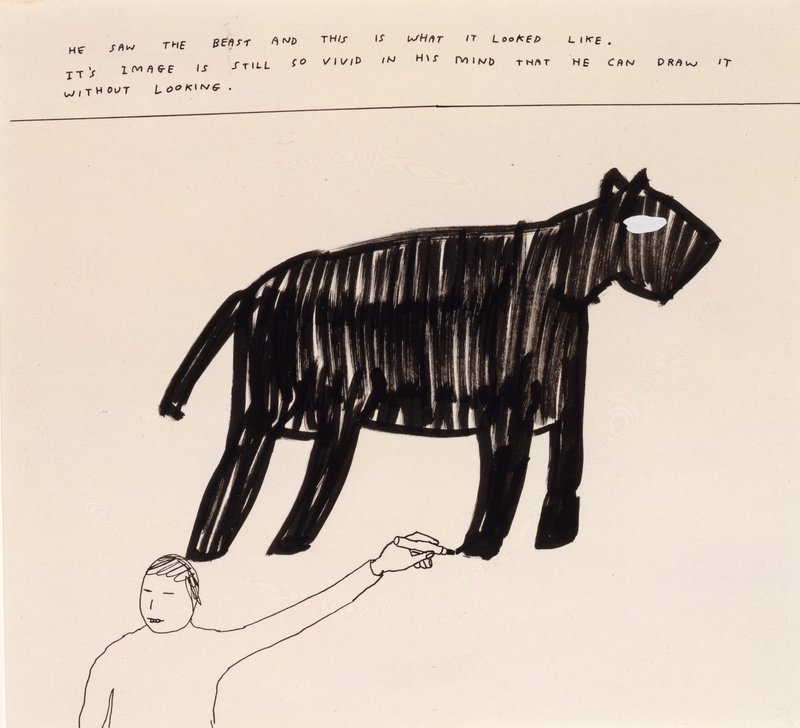

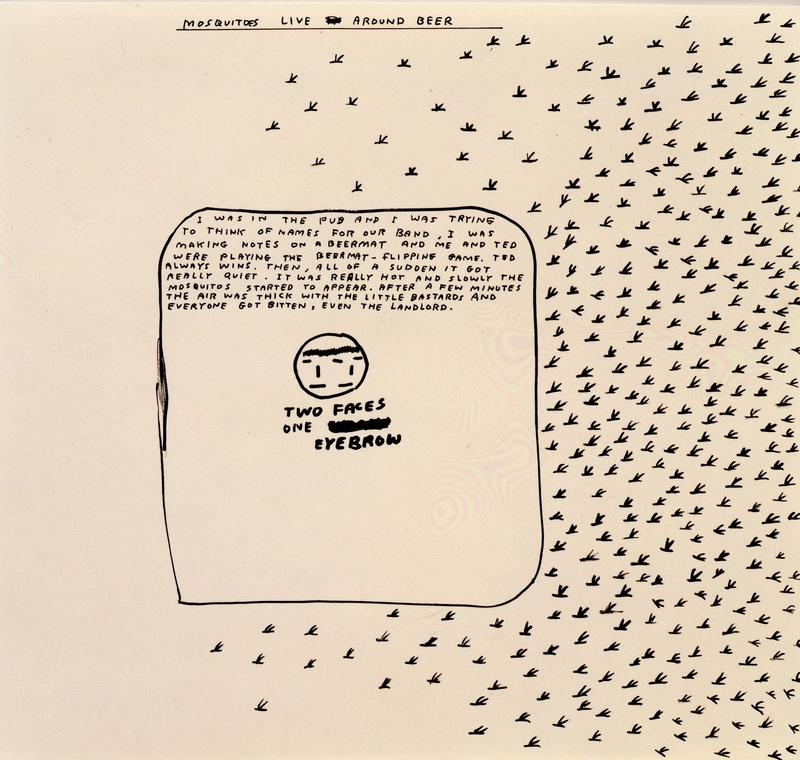

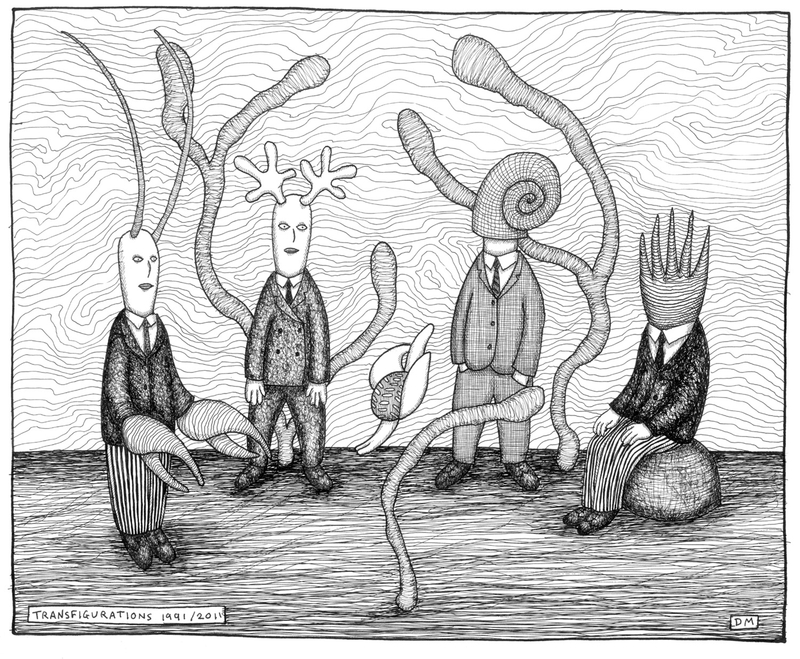

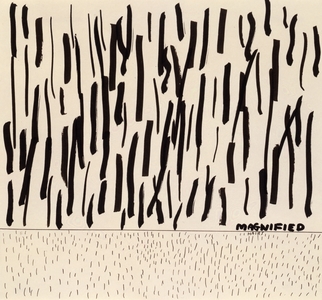

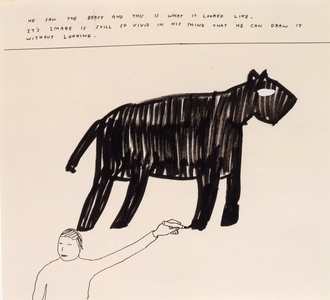

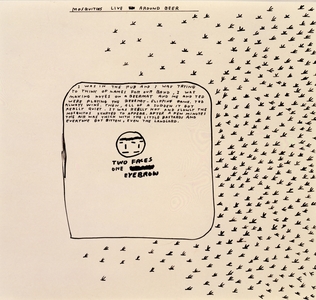

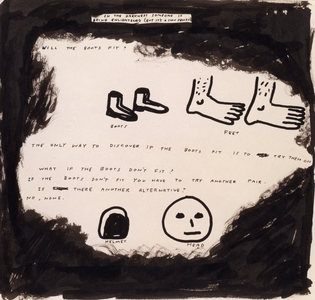

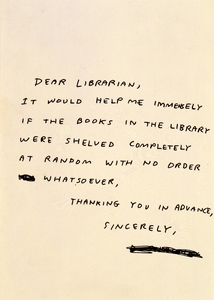

Drawing is the foundation of Shrigley's practice, putting him at odds with other big names in the art world working in the more traditionally lauded mediums of painting and sculpture. Typically, Shrigley's work merges impactful graphic design and twee illustration with quippy, quotable snippets of text on life. It has a certain genteel nature that is not just feminine and girlish, but also playfully boyish and acerbically male: if one can navigate the artist in such binary terms.

Perhaps his illustrations can be read in these terms due to the childlike, tactile nature of the marks on the paper, harking back to our earliest, formative days. His draughtsmanship has enabled a certain shared wit and celebration of the banal, the depressing, the scary and the silly.

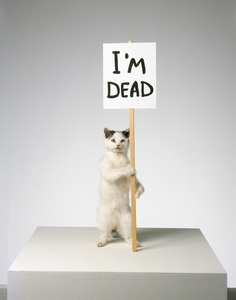

His existential simplicity on paper has gone on to inform his other practices. After drawing came music videos, sculpture, paintings and books. Text is at the core of Shrigley's practice. The juxtaposition of sparse and playful image with often confronting wording was, and still is, refreshing and jarring in equal measure.

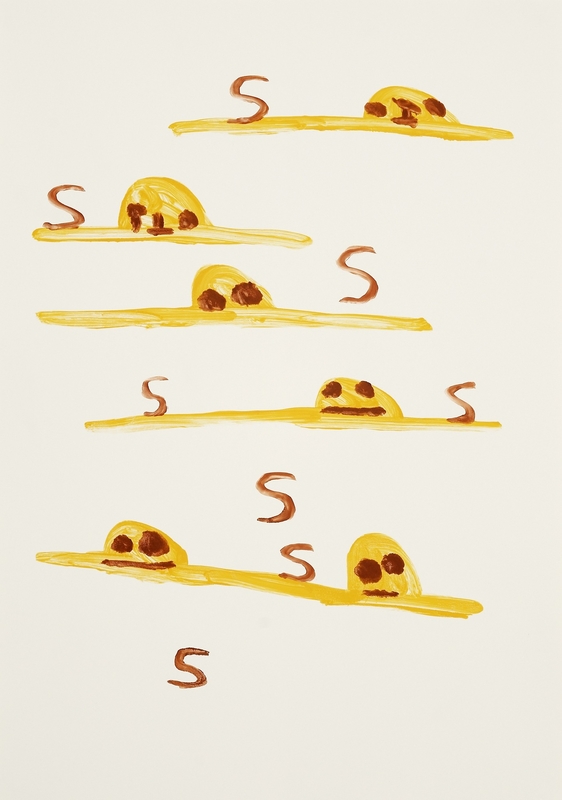

Always, the tie between domesticity and drawing has been Shrigley's signature flavour. As the artist moved through the 1990s and 2000s, movements ranging from Britpop to the Young British Artists influenced his work, prodding at our senses in a way that is less snarky (though he can be) and altogether wry, astute, subversive.

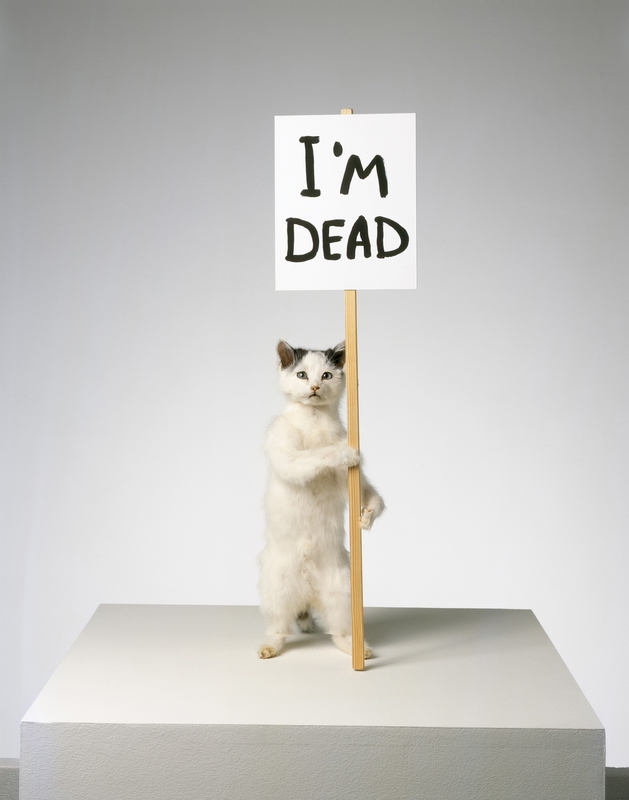

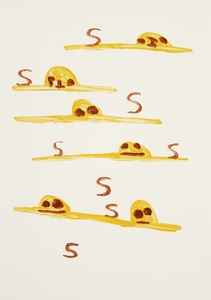

He plays with ideas of things found in the average home – food, pets, tools, toys – and he studies how those things are representative of our social conditioning and domestic expectations. Often, his work could be read as representing a real need for home: to burrow away, to hibernate, to shirk responsibility and nest in one's thoughts.

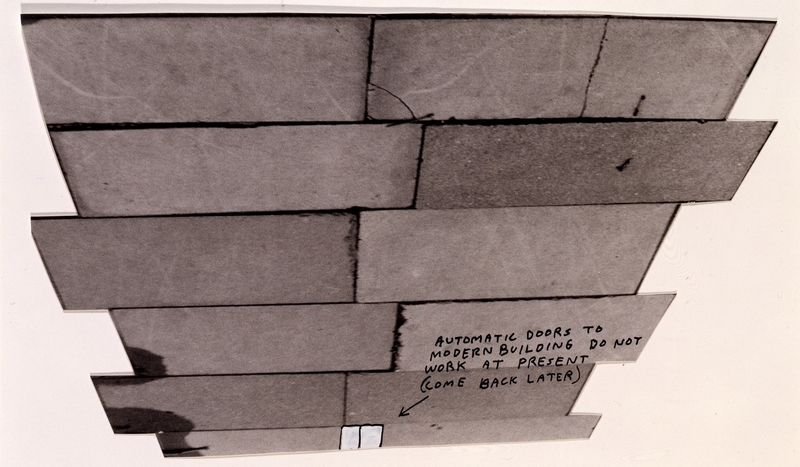

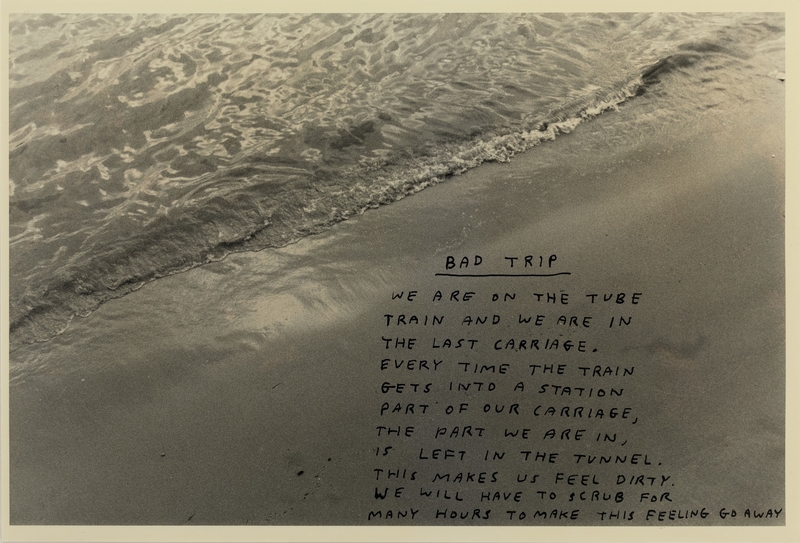

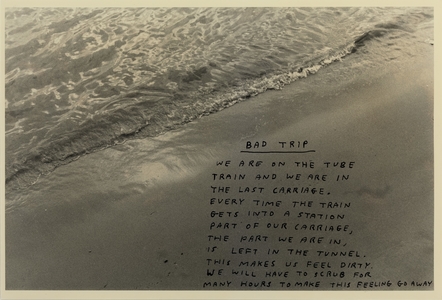

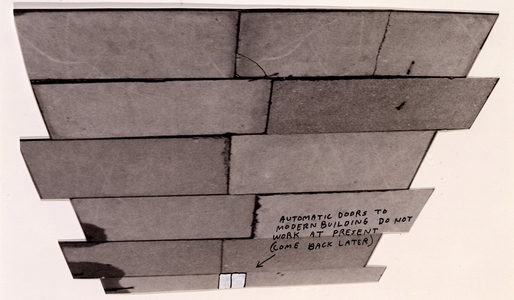

In Bad Trip (1997), the doomier parts of Shrigley's popular psyche tapped into a universality. He writes a description of feeling dirty on the Tube directly on the surface of a photograph of waves on the beach. The work grapples with the disconnect between the surface-level glamour of London and the challenges and turbulence of living there, like the feeling of being sullied from moving from one place to another or the weighty emotional angst of getting left behind.

Technological advancements such as new Tube lines and economic structures such as the Docklands cropping up only did more to serve the neo-luddite complexes of this generation. Shrigley's work might also be read as a nod to the acid rave crowds with the double entendre of its title, referencing a drug-induced high and the resulting comedown.

Shrigley's graphite and other monochromatic works came to be an interesting foundation for the technicolour palettes of his later work. Often, the work that one recalls of Shrigley is more buoyant and less elusive than his early successful drawings. Some 25 years later, in 2013, the artist was nominated for the Turner Prize. A quarter of a century had passed since his early drawings, but the corners of Shrigley's dark and thoughtful mind were of great public interest.

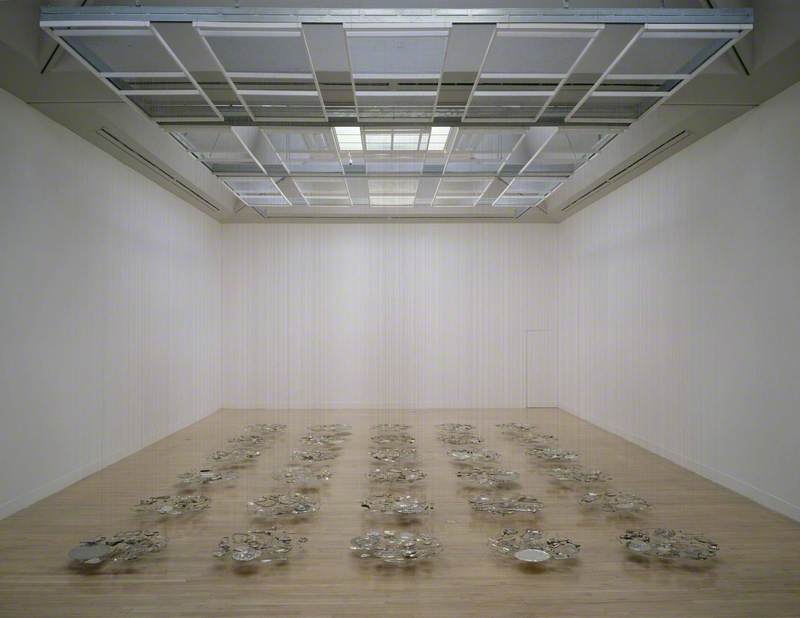

His room in the Turner Prize exhibition served as an interactive exhibit that placed spectators in a life drawing class. Somewhat eerily, the subject was a naked sculpture of a boy urinating into a metal bucket at his feet. Sculpted with oversized ears and nose, the artist referenced his tendency to expand on features in an absurdist, cartoonish fashion. The attendees' drawings were then fixed to the gallery walls, creating a collaborative project between artist and audience – and continuing to foreground the artist's fascination with drawing.

This altogether alarming and confronting work was a departure from the gentleness of his drawings and paintings. It also addressed doubts that many have raised with Shrigley's work. Indeed, similar doubts are raised whenever an artist makes work that is less perfected in the cosmetic, linear sense. Shrigley continues to push at the boundaries between mediums by breaking form, breaking figurative expectations and breaking his own usual way of practice.

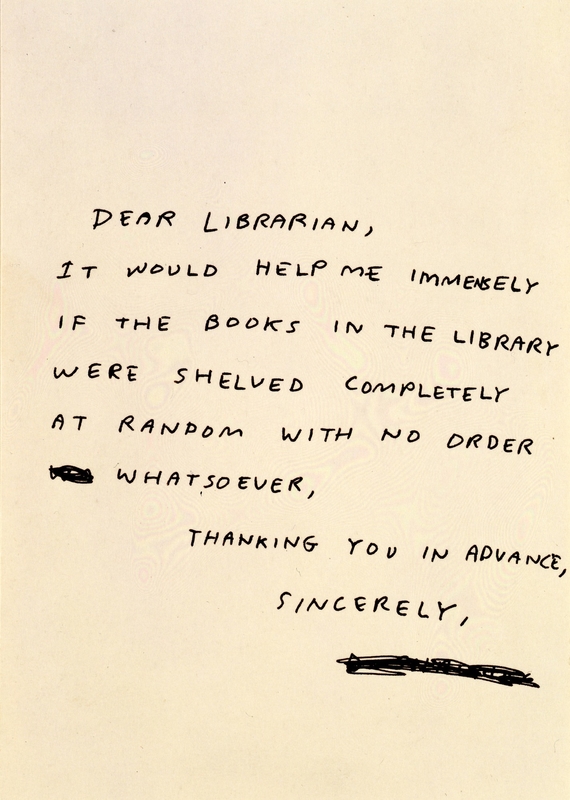

In typical fashion, the artist has both broken the mould and remained self-referential in his latest work. A longstanding affinity for working with paper can only be made interesting with a dose of controversiality – and a glint of Fahrenheit 451.

His most recent major contract was a conceptual exhibition 'Pulped Fiction', announced in 2023. Shrigley purchased thousands of copies of Dan Brown's The Da Vinci Code, pulped them, made paper and printed copies of George Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four.

View this post on Instagram

In an age of cosmetic imitation, with a political landscape rife with plagiarism and blatant lip service, Shrigley once again hits the mark in his sort of shrugging social commentary that goes 'well, look what we've done. Better make lemonade.'

Alexandra Pereira, writer and performer

This content was funded by the Bridget Riley Art Foundation