Today, Art UK launches Curations – a new tool that lets anyone bring together and write about artworks on the site. We asked curator Kathleen Soriano to share her tips on how she goes about creating an exhibition, to give us all a few pointers...

Exhibition making is innate... at least it is for me, after over 35 years of doing it, and honing that particular skill. How do you explain how to do something when it's become so instinctive, so automatic, that you don't actually know how you do it? Well, that was the challenge thrown at me by Art UK and given that one of my many dirty little secrets is how often I use their indispensable website for exhibition research, I owed it to them to try and consider... how do I do it?

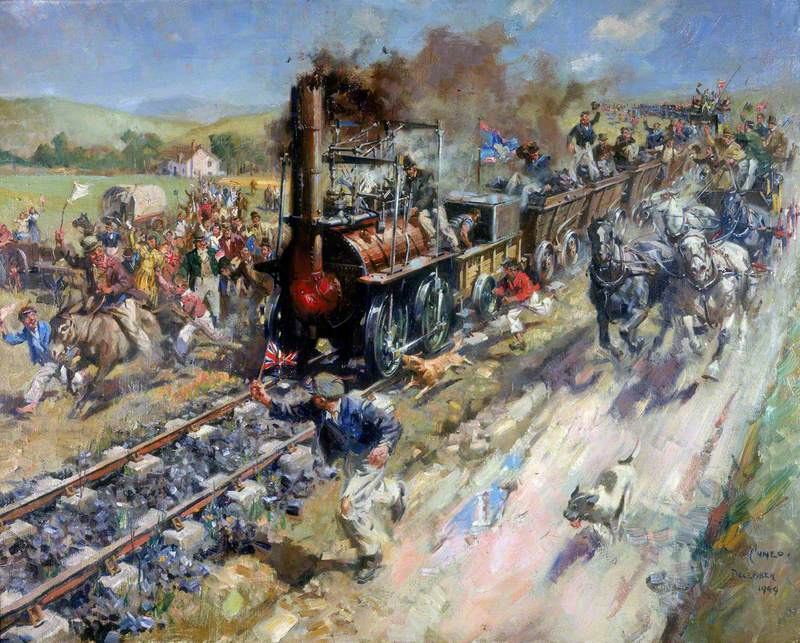

Kathleen at Art UK's exhibition during the London Art Fair in 2018

Step 1 – The good idea

There are already millions of exhibitions out there so what is going to make yours different, more relevant, more appealing? More importantly, who are you making it for? If simply for your own pleasure, you can pretty much do what you want and indulge all your art historical vices, otherwise reflect on what you want to achieve with it.

Are you aiming to reach a certain audience, to deliver a key message or to champion a deserving artist? Is it a 'campaigning' sort of show, like my climate change one at the Royal Academy of Arts back in 2009 ('eARTh: Art of a Changing World'), or my 2019 exhibition on the work of Syrian artist Sara Shamma examining the issue of modern-day slavery at King's College London?

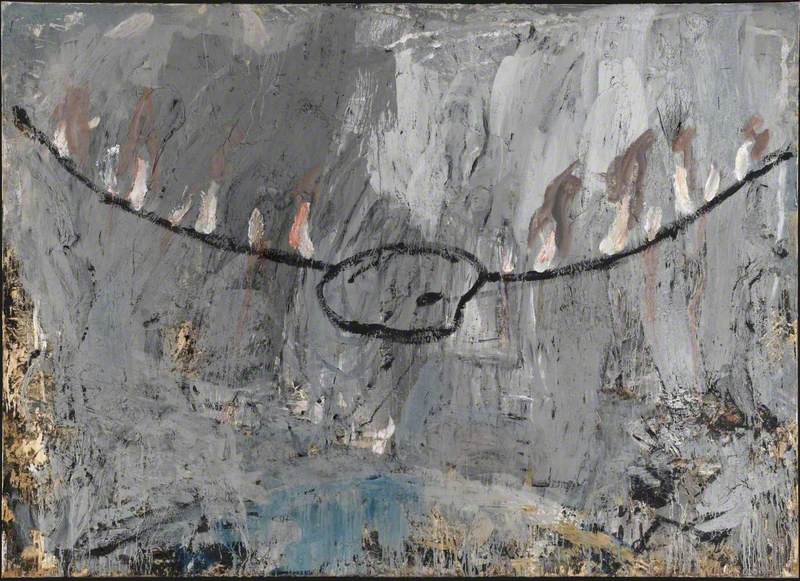

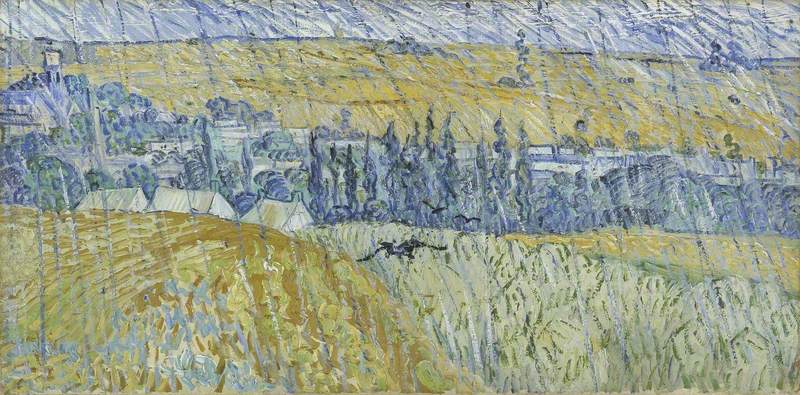

Is it to champion something you care about? Such as the show I created celebrating the incredible work of Art UK at the London Art Fair in 2018, when they were the Official Museum Partner. Alternatively, is it about art history and great artists, such as my Van Gogh show at Compton Verney in 2006, or 'Anselm Kiefer' at the RA in 2014? Or maybe it is simply about truth and beauty like the 'Bronze' show that I commissioned for the RA in 2012.

Step 2 – Filthy lucre

Once you are clear on your idea, in the real world one has to work out whether or not it is even viable. Can you get the loans (Leonardo da Vinci – probably not, unless you're The National Gallery), can you afford the insurance (yes, if like many of the UK's major museums and galleries you are blessed with the Government Indemnity Scheme), how much is the whole thing going to cost (including all the expensive object couriers, showcase construction, design and display, etc.) and, even more importantly, how much money will it make?

Exhibitions at our major institutions are finely tuned beasts where income and expenditure have to balance, alongside blessed injections of corporate sponsorship, plus trust and foundation support, without which many of us would not be able to make these shows happen. That income usually includes ticket sales as well as profits from the shop and café, and evening hire of the exhibition for private events. All of these requirements for income put pressure back on Step 1 (the good idea). If the good idea is unable to deliver footfall then maybe it isn't such a good idea.

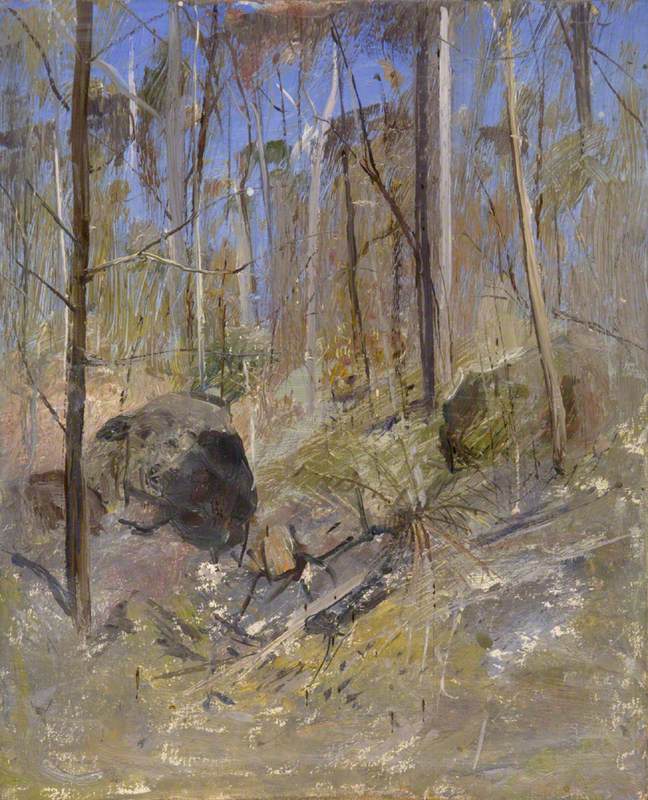

Although, that isn't strictly true. Sometimes an exhibition that isn't going to be overwhelmingly popular is a truly great idea. Institutions and curators – especially those with the platform of major institutions, as I had at the RA – have a duty to broaden the artistic canon and to bring new and fascinating artists to the world's attention. My 'Australia' exhibition at the RA in 2012, and more recently my exhibition on the nineteenth-century Norwegian landscape artist, Harald Sohlberg, for Dulwich Picture Gallery (2018), were examples of exactly that.

Since 'Australia', there have been more exhibitions on Australian artists in the UK and Europe than I had witnessed in the previous 30 years – The National Gallery showing Australian Impressionists for the first time in 2016, and the Aboriginal artist Judy Watson is due to open an exhibition at Ikon Gallery in Birmingham. Where the canon can be broadened for all of our pleasures and wonderment, or where new academic research or revelatory study can be brought to light, even if it is initially for the smallest audience, there is enormous value and lasting legacy.

Art UK's exhibition at the London Art Fair in 2018

Step 3 – Rhythm and pace

Now that you have your good idea, you know why you're doing it and for whom, and you're confident that it won't bankrupt you (either financially or intellectually), you need to shape it. Different shows require different approaches. If it's a single artist show or mainly art historical, I tend to let the works of art tell me how they want to be organised – much as I did with the work that featured in my book on women artists, Madam & Eve: Women Portraying Women (co-authored with the artist Liz Rideal). This is not meant to suggest that I have a particularly unique psycho-spiritual connection to art but more to say that when I lay out the work of an artist I tend to see clearly how it wants to be grouped – according to theme potentially, or medium, or date, or maybe even colour.

That emotional – or maybe it's an intellectual – response always has to be pragmatically tempered by the realities of context. What scale is the space that you're working in? Are there a sequence of rooms that mean that only one can accommodate sculptures, or larger works, or that dictate the hang in other ways? Lower lighting requirements for works on paper might encourage you to hang them all together rather than try and intersperse them with oils when your lighting system doesn't have the flexibility.

If the show is going to be supremely popular (read Van Gogh, David Hockney, Monet to mention a few), maybe you need to hang the works a few inches higher than you would normally so that they can be seen over the 4 or 5 heads that will be in front of you in the gallery (at least in pre-Covid-19 times). An understanding of the issues becomes like second nature but beware, every gallery space or room will have its own idiosyncrasies and it is not until you have worked in them and hung in them that you will truly know them and how to they need to be handled to best effect.

At all times, the issue of rhythm and pace to the show needs to be considered. Rather like a piece of music, the flow of an exhibition needs to move the visitor through a series of varied movements, each with their own revelations and moments of surprise, building finally to a crescendo that aspires to ensure that the visitor leaves on an emotional high, either in response to the impact of the works themselves or to the argument that they have walked through.

That argument does not have to be literary but can also be visual. Visitors absorb exhibitions and understand aesthetic and artistic value in different ways. This came very much to the fore when we were planning the 'Bronze' exhibition at the RA, as we constructed a show that allowed for many routes through the argument. For some, value and appreciation were found in the aesthetics of the objects – truth and beauty; for others, they needed to understand the complexities of construction and to be left in awe at the skill involved; whilst some found their reward in the context and history of the objects themselves. There is no one audience type and no single way in. Nor does the music always get louder as the show progresses – sometimes it starts with a bang, though it should never end with a whimper, is my advice.

Art UK's exhibition at the London Art Fair in 2018

Step 4 – Beg, steal or borrow

Once you have designed your ideal shape and selection the hard work begins, as now you need to persuade the people who own the works to let you borrow them. Major institutions around the world will ask for a minimum of six months' notice, but more often a year, so that they can process the potential loan through their system. Is the work safe to travel? Can the organisation do without it for the time it's away? Does the exhibition theme have integrity and warrant the loan – is it breaking new ground, adding to the understanding of the artist or period? Does the lending institution have a good relationship with your institution?

Most exhibitions at our major arts organisations are put into the schedule a good two to three years before they happen, in order to allow for this extended period of loan negotiation. The consequent re-appraisal of the contents of a show, as it is impacted by loan refusals and their replacements, in turn, will shift the shape of the show and require renewed thematic massaging. When I arrived at the RA in 2009 they had been without an Artistic Director for nearly two years so the cupboard was bare and I had to create exhibitions at breakneck speed. Happily, when I left in 2014 my legacy was a commissioned programme that stretched well into 2019 and that hopefully gave my successor some comfort when he arrived.

Pro tip: don't steal...

Art UK's exhibition at the London Art Fair in 2018

Step 5 – The best bit

You've been working on the gallery scale model for two years, sticking mini-paintings onto foamboard walls with blu-tak, shuffling them back and forth as loans fell through and new issues with the spaces emerged (I never forget the electricians in one institution who suddenly remembered that there was an access panel immediately behind the large Anish Kapoor work that we had just built, causing the last-minute reconstruction of the sculpture).

Finally, you are in the freshly painted exhibition space with the real objects arriving in early morning flurries from the art transporters. Opening up the exquisitely designed, purpose-built crates and slowly removing the layers of packaging to reveal the treasures within is an excitement that never leaves you as a curator. Once out of the box and condition checked by the conservators to make sure that they have travelled safe and well, the next step is to position them carefully against the gallery wall in the same spot that you had them blu-takked to in the model. With luck, that is where they will stay but some curators just cannot resist the jiggle, shuffling works around until they 'work' so that scale, aesthetics, argument and the feel of that single space all work seamlessly together to create a perfect whole.

If you are lucky enough to work with a designer or architect on the build, the colours and the graphics, they will have supported you (and the artist) in realising your vision and will have challenged and surprised you along the way, hopefully, as well as coming up with some miraculous solutions to installation problems that you just could not work out for yourself (such as how to make a single large bronze nail look interesting in a showcase).

Step 6 – Let it go!

Once the show is up, the opening launch party has been had and artist, curator, institution, lender, sponsors, etc., all celebrated, the institution goes to work on making sense of what you have made for the many audiences who will, hopefully, come.

Just as the exhibition begins its life and stands on its own two feet, I always feel a keen sense of loss. Of course, I am delighted that the project (ideally supported by a fully-illustrated catalogue) is out there for the world to see and enjoy, but it is no longer mine to fiddle with, to nurture, shape, re-shape, destroy and rebuild afresh, which is maybe why one of my fondest memories of my time at the Royal Academy goes back to the formal toast that we would always make at dinner on the opening night of our shows – 'Honour and glory to the next exhibition'.

Kathleen Soriano, independent curator, art historian and broadcaster