Born in 1926 in the British colony of Guiana, modern-day Guyana, Aubrey Williams is often considered an Abstract Expressionist. Yet Williams, inspired by a host of influences, including classical music, tropical birds, astrology and pre-Columbian iconography, created paintings that, in incorporating figurative, symbolic and abstract elements, resist straightforward classification.

Early years

The son of a civil servant and eldest of seven, Williams was born in Georgetown, Guyana's capital. He began drawing as a child, taking lessons from a restorer of religious paintings in Guyanese churches, before joining the Working Peoples' Art Class, aged twelve.

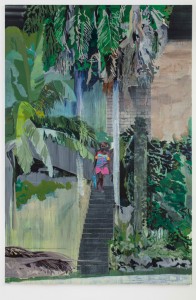

Guyana was then a British colony, its economy dominated by the sugar industry and Williams, alongside developing an art practice, trained as an agronomist, in 1944 taking up a post as Agricultural Field Officer on the coast. His encouragement of exploited farmers to claim rights against British-owned sugar plantations soon resulted in his banishment to the remote north-western rainforest settlement of Hosororo. There, Williams met indigenous Warrau Amerindians whose history and culture came to inform much of his work.

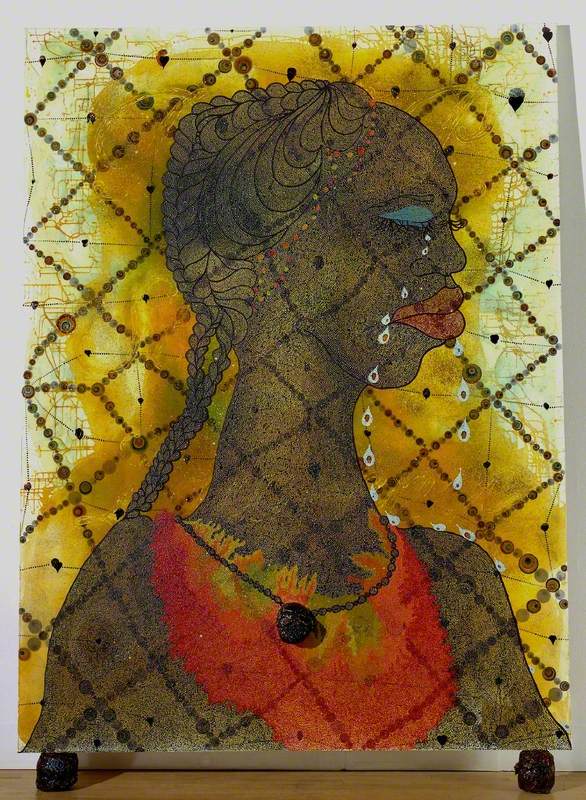

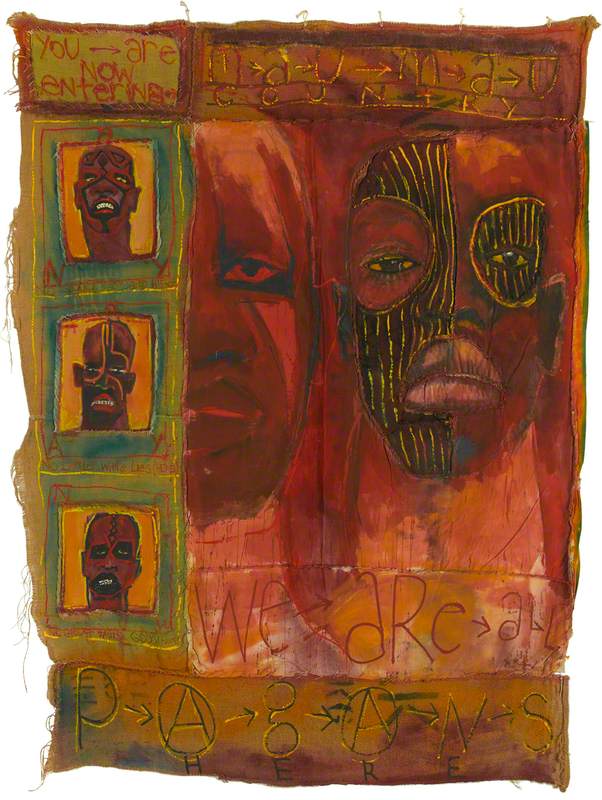

In Tribal Mark, Williams depicts a bone-like claw or glyph, which he recorded as being part of the Warrau's pictorial language. Williams repeatedly utilised this symbol in his work, describing it as 'a strange, very tense, slightly violent shape' that 'has haunted me all my life... a subconscious thing coming out'. For him, the shape's violence represented something of the violence of humanity, especially that of colonising forces. Williams's time in Hosororo also prompted his artistic concern with the natural world, including an interest in ornithology.

Throughout his career, Williams painted a variety of birds, in particular depicting predators, raptors and waterfowl. Some examples can be seen in the archive of his personal papers at the Tate. He was drawn to birds as, for him, they represented 'the unattainable – possessing qualities we can only admire from our limited human state,' such as 'the gift of direction-control' during migration.

After two years in Hosororo, Williams returned to Georgetown where many of his friends had joined the People's Progressive Party, at forefront of fighting for Guyana's independence. The government now deemed Williams a political agitator for his role in galvanising exploited farm workers and opened a dossier on him. Consequently, following a plantation shooting, he left Guyana for his own safety, only returning with Guyana's independence.

Move to Britain in 1952

Williams migrated to Britain in 1952, obtaining a scholarship on an Agricultural Engineering course at Leicester University. But, finding the university had little to teach an experienced agronomist, he dropped out and instead toured Europe. Here, Williams came face to face with German Expressionist paintings and met Pablo Picasso. Picasso, according to Williams, was a great disappointment, not treating Williams 'as another artist', despite his introduction as such, rather requesting that Williams pose for him, regarding him only as 'something he could use for his own work'.

Later, in 1954, Williams settled in London with his then-fiancée Eve and enrolled at Saint Martin's School of Art. He became an energetic participant in the London art world, attending and exhibiting at galleries across the capital. Two Tate exhibitions on the subject of Abstract Expressionism proved especially important to Williams. 'Modern Art in the United States' (1956) and 'New American Painting' (1959) enabled him to see the works of American Abstract Expressionists first-hand.

Williams greatly admired them, describing Jackson Pollock as 'our God!' and Kline, Newman, Rothko and de Kooning as 'all great'. Yet the featured artist who had the most profound effect on Williams was Arshile Gorky.

Gorky fled Armenia during the Turkish persecution, settling in America in 1920. His experience of displacement and his interest in natural forms informed Gorky's work and chimed with Williams's own artistic concerns.

Caribbean Artists Movement (1966–1972)

In 1963, having already exhibited at notable London galleries, including the prestigious New Vision Centre Gallery, renowned for exhibiting non-British artists, Williams won the only prize at the First Commonwealth Biennale of Abstract Art.

Yet, despite his initial success, by the mid-1960s, Williams found himself increasingly marginalised from the British art world, confronted by at best institutional indifference and at worst hostility – his work framed solely in terms of 'otherness'. Consequently, he suffered from 'feeling terribly isolated, physically and intellectually' – made to feel an outsider.

In response, Williams took a leading role in founding the Caribbean Artists Movement which operated in London between 1966 and 1972. The movement, associated with artists and intellectuals including Ronald Moody, Stuart Hall and Orlando Patterson, celebrated and promoted the work of artists, writers, dramatists, filmmakers, thinkers and musicians from the Caribbean diaspora. It provided a supportive and intellectual environment for diasporic creatives to work, meet and relate to each other through conferences, exhibitions and informal meetings.

Beyond Britain (1966–1980s)

From the mid-1960s, Williams, although participating wholeheartedly in the Caribbean Artists Movement, spent less time in London. In 1966, he travelled with his wife Eve and their 18-month-old daughter to Guyana to celebrate its independence, and in the 1970s he set up studios in Jamaica and Florida.

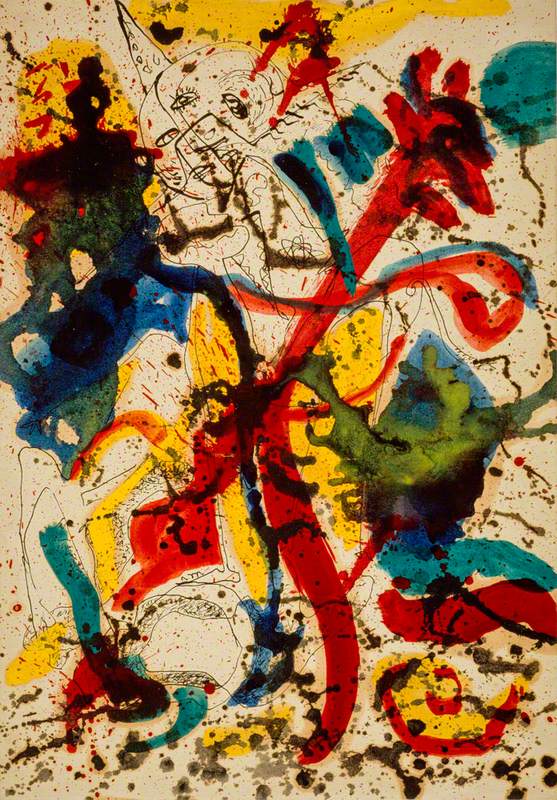

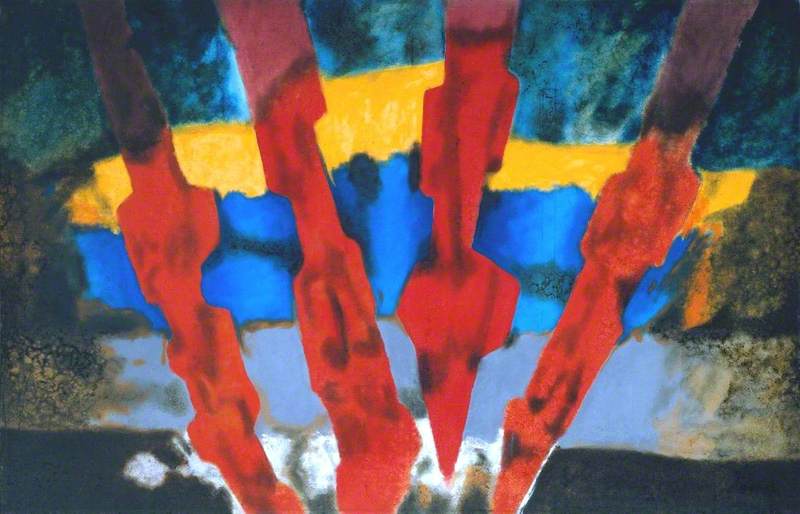

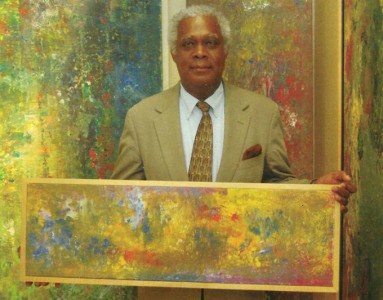

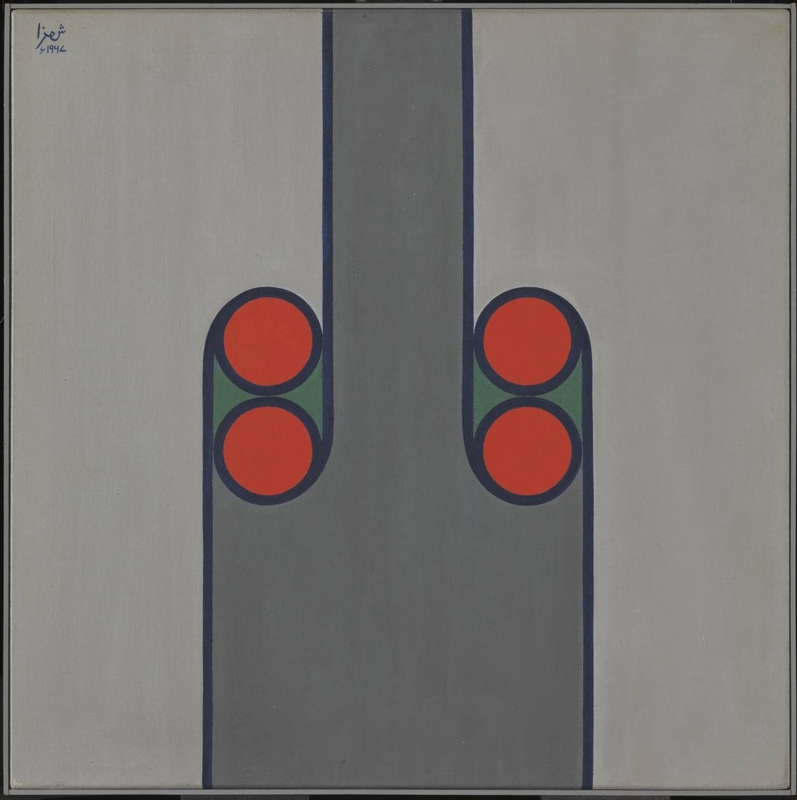

From the 1970s onwards, Williams worked between studios in Jamaica, Florida and London. During this period, he produced some of his best-known paintings including the 'Shostakovich Series' – 30 large-scale oils, inspired by the symphonies and string quartets of the twentieth-century Russian composer Dmitri Shostakovich.

Williams first heard Shostakovich's Symphony No. 1 in his mid-teens when he was struck by its 'profound visual connotations' and ability to evoke synaesthetic feelings of colour. In response, Williams paid painterly homage to Shostakovich, creating a series rich in explosive, vibrant colour that sought, like Shostakovich's music, to arouse sensorial feelings in the viewer.

Symphony No. 6 by Dmitri Shostakovitch

Aubrey Williams (1926–1990)

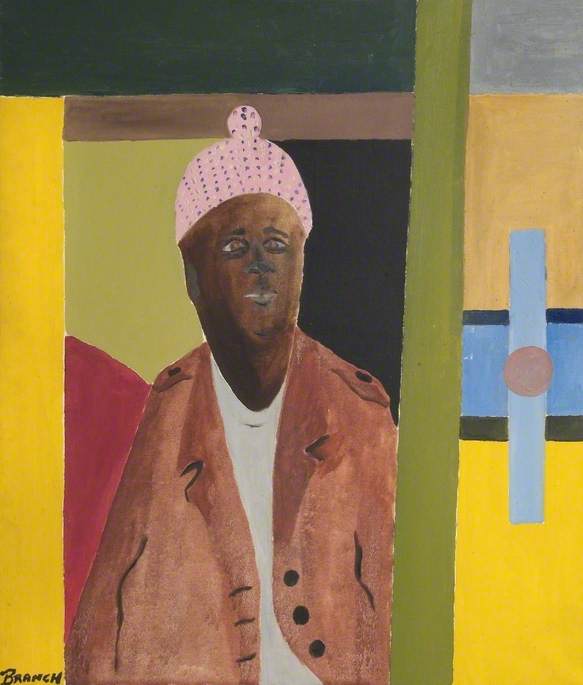

Williams's celebration of the expressive potential of colour and sweeping gestural style earned him an exhibition at the Commonwealth Institute of Art in 1981 and a reputation as an Abstract Expressionist. Yet he never abandoned representational work, often blending abstract techniques and motifs thus defying mainstream modern art conventions, whose strictures kept them apart. Yet it was Williams's ability to cross boundaries of abstraction and figuration that makes his painting so powerful.

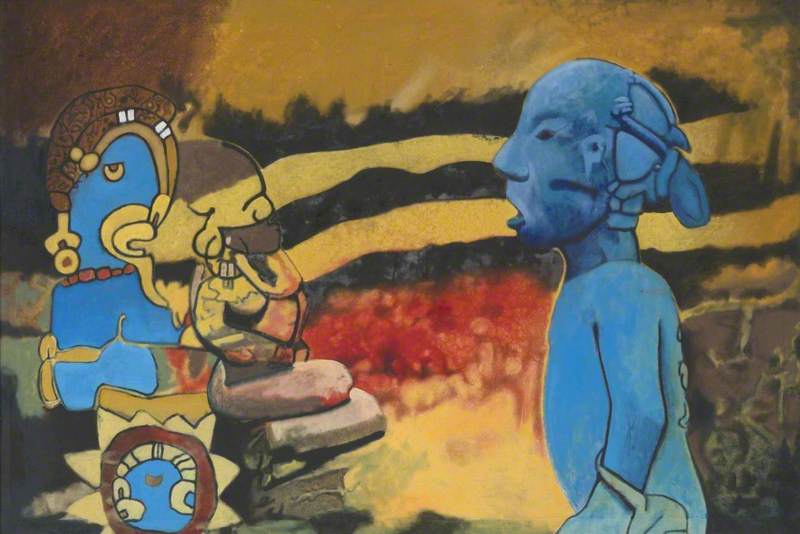

In Olmec Maya – Now and Coming Time, Williams, drew on his knowledge of South and Central American ancient cultures. He foregrounded Mayan and Olmec icons against a fiery abstract backdrop to explore parallels between what he described as 'Maya mistakes' and comparable developments in 'modern humanity'. He believed the Maya created technology that eventually destroyed their natural environment – a fate, in his view, the modern world would soon face.

Williams's refusal to be pigeonholed as an Abstract Expressionist, combined with endemic institutional racism within the British art world, meant he was omitted from every major survey of British painting in his lifetime. Only after his death in 1990 did he start to garner widespread critical acclaim – his archive being acquired by the Tate in 2001. Since then, Williams has begun to be celebrated as a formidable artist whose extraordinary transnational experience of place and time, deeply felt relationship with Central and South America's nature and history, and critical knowledge of western painting informed his remarkable, genre-defying work.

Jessica Boyall, independent curator, researcher and writer

Further reading

Anne Walmsley (ed.), Guyana Dreaming: The Art of Aubrey Williams, Dangeroo Press, 1990

Imruh Bakari, The Mark of the Hand, Arts Council/Kuumba Productions, 1987

Rasheed Araeen, 'Conversation with Aubrey Williams', Third Text, vol. 1 no. 2, 1987, pp.25–52

Reyahn King (ed.), Aubrey Williams: Atlantic Fire, National Museums Liverpool and October Gallery, 2010

Kobena Mercer, 'Aubrey Williams: Abstraction in Diaspora', British Art Studies 8