Playing dress-up – kids love it, and let's be honest, adults do too. We tend to think of cosplay, a combination of the words 'costume' and 'play' which usually describes someone dressing up as a fictional character, as a relatively new social activity. Marvel, DC Comics and Japanese manga and anime characters spring to mind. But this playful, celebratory activity has been with us for much longer. Whether you call it an art form or just an excuse to have fun, cosplay is a fascinating exploration of who we are and what we value.

Night Masquerades (The Revels of the Ungodly)

c.1588

Joos van Winghe (1544–1603)

Masquerade balls were much loved in the fifteenth century, and public costume festivals were common in Renaissance Italy. Fancy dress parties were so popular in the nineteenth century that costuming guides appeared, and newspapers reported on costume balls. Fast forward to the modern era, and fan costuming became an essential part of attending 1960s science-fiction conventions, while elaborate handmade outfits can be seen today at cosplay events all over the globe.

A Fancy Dress Ball, Manchester

1828

Arthur Perigal the elder (c.1784–1847)

But did you know that in eighteenth-century European portraits we find a trend of society women dressed as ancient mythical Greek goddesses – including Diana, Venus, Hebe and Flora?

George Romney (1734–1802) and Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792) in England and Nicolas de Largillière (1656–1746) and Jean-Marc Nattier (1685–1766) in France were key artists in this genre. This period was a hotbed of social change and transformation in both countries. Although we see wars in France and problems in colonial Britain, we also see industrialisation and growth on a huge scale.

Kitty Fisher (1741–1767) as Cleopatra Dissolving the Pearl

1759

Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792)

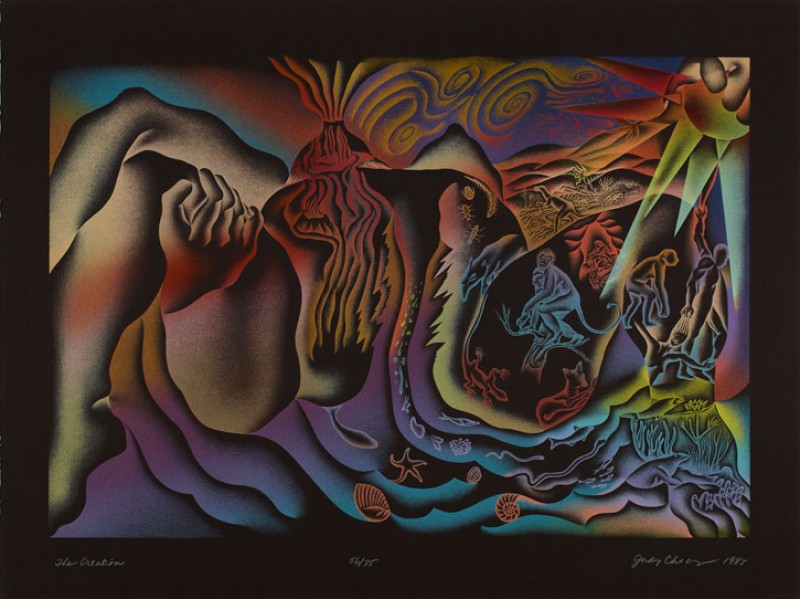

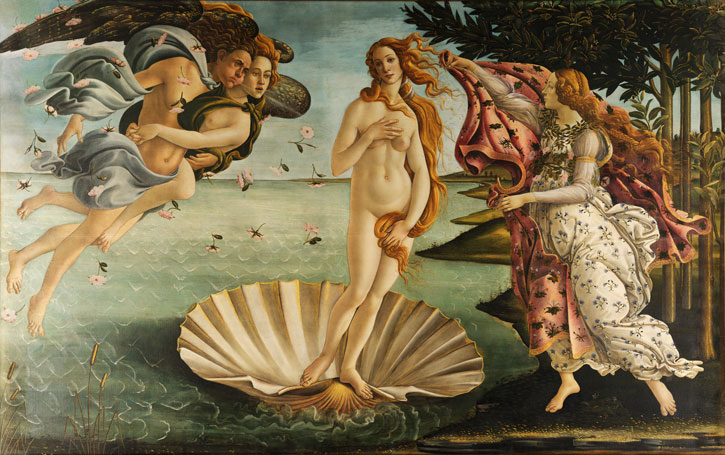

This socially mobile period saw the emergence of writers, artists, actors and beautiful society women – including those from poorer backgrounds who rose through the ranks – as 'celebrities'. Previously, artists painted an anonymous, composite woman as a goddess, a blank canvas onto which they could project the best of what their society considered beautiful and virtuous. Perhaps the most well-known example is The Birth of Venus (1486) by Sandro Botticelli (1444/1445–1510).

The Birth of Venus

c.1485, tempera on canvas by Sandro Botticelli (1444/1445–1510)

But in the eighteenth century, artists presented real women as goddesses. The first real-life woman to take on the role of the goddess was likely Saskia van Uylenburgh. Dutch painter Rembrandt (1606–1669) painted his first wife as the embodiment of Flora, the Roman goddess of spring and fertility.

Saskia van Uylenburgh in Arcadian Costume

1635

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669)

In the eighteenth century, a desire to combine history painting and portraiture – the two highest genres of art according to the French Academy – resulted in the emergence of the term 'portrait historié'. This was used to describe portraits of known individuals dressed up as biblical, literary or mythological figures. But this was mostly a gendered act – portraits of men in mythical roles were not common. Presumably men were considered already fully costumed as captains of industry, political leaders or decorated war heroes!

An exceptionally rare example is Nattier's 1746 portrait of the Duc de Chaulnes as Hercules, the original adventuring strongman.

Duc de Chaulnes as Hercules

1746, oil on canvas by Jean-Marc Nattier (1685–1766)

What can goddess paintings tell us about eighteenth-century life? Let's take a look at a few examples, as the messages can be diverse.

The image may be a signal to the wider society about the virtues women should cultivate. Athena was goddess of wisdom. Aphrodite was goddess of love and beauty. Diana was associated with virginity (as well as hunting). Hebe was a goddess in the full bloom of youth. Choosing a mythological character meant directly associating a woman with the ideals of the ancient classical civilisations, elevating her to the position of divine womanhood.

Elizabeth (c.1760–1826), Viscountess Bulkeley, as Hebe

c.1775

George Romney (1734–1802)

Marie-Joséphine-Louise de Savoie (1753–1810), comtesse de Provence, as Diana

François Hubert Drouais (1727–1775) (after)

Some paintings might be considered marriage adverts, social propaganda encouraging women to strive for the role of 'wife and mother' (and letting men know who was available, of course!)

Reynolds created a huge triple portrait of the aristocratic Montgomery sisters as the Three Graces, personifications of beauty and elegance. These graceful daughters of Zeus are shown worshipping a statue of Hymen, the Greek god of marriage and fertility.

However in some works we see signs of change in women's roles within society. It is certainly true that there were women living outside traditional rigid conventions – having affairs or challenging social norms. The irony is that wealthy women who overstepped social boundaries could be ostracised yet also celebrated – scandal was glamorous. A woman could work with an artist to cultivate an image and enhance or repair her reputation. In fact, goddess depictions were often a collaboration between artist and sitter.

Emma Hart, later Lady Hamilton, rose from poverty and obscurity to the heights of fashionable society. Rather than being painted as, for instance, the pure and virginal Diana, she played with notions of womanhood and sexuality with deities such as Calypso, the egocentric and obsessive nymph who imprisoned Odysseus.

Emma Hart (c.1765–1815), Lady Hamilton, as Calypso

1791–1792

George Romney (1734–1802)

In France, the sensuous, light-hearted style of Rococo gave us informal portraits, revealing the playful personality of the sitter. Nattier was noted for his portraits of the ladies of Louis XV's court dressed in mythological costumes. He aspired to be a history painter, but portraits were a more lucrative undertaking. By combining mythological landscapes with true likeness portraits, he captivated audiences and flattered his subjects who revelled in their sumptuous, exotic attire.

Madame de Pompadour as Diana

1746, oil on canvas by Jean-Marc Nattier (1685–1766)

Nattier also painted French princess Mademoiselle de Conti (who became Louise Henriette de Bourbon by marriage) as a river goddess. Although raised in a convent, it is said she had a wild and scandalous (though sadly short) life. Her lovers ranged from a king and a duke to artists, gardeners and soldiers. Beautiful, playful and light-hearted, the water nymph seems an obvious choice for this audacious young woman, and the nipple just escaping from her gown is perhaps a hint at her passionate nature.

Louise-Henriette de Bourbon-Conti (1726–1759), as a River Goddess

c.1738

Jean-Marc Nattier (1685–1766)

Venus, the Roman goddess of love, beauty, desire and pleasure is an obvious choice for this stunning celebrity portrait of the famous Anglo-Irish society hostess, Elizabeth Gunning. She was so revered that people would gather in public places just to catch a glimpse of her.

This portrait helped establish Reynolds as the premier portrait artist of the period. His 'Grand Manner' style, which referenced classical motifs, elevated portraiture from vanity images of the rich celebrating their wealth to the status of high art. Reynolds worked long hours in his studio – at the height of his career, he would receive five or six sitters every day.

Elizabeth (née Gunning), Baroness Hamilton of Hameldon and Duchess of Argyll

c.1760

Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792)

Gunning wears the contemporary red velvet and ermine robes of the aristocracy – we do not want to forget that this is a member of the elite, after all. But she also has the flowing Grecian gown, the loose cascading hair and the doves we would associate with Venus. Elizabeth met the 6th Duke of Hamilton at a Valentine's Ball when she was 19. The Duke was so enamoured of Elizabeth that he married her that very same night.

Sophia Catherine Musters was described as a beautiful but unhappy wife. In this stormy scene by Reynolds, which depicts her as Hebe, daughter of Zeus, Sophia wears a dark diaphanous gown, with wind-blown hair and vibrant eyes. Hebe was celebrated as a goddess of youth – like a good daughter she served divine food (such as ambrosia, supposedly served to Greek gods) at heavenly feasts. However, she was also the patron goddess of the young bride.

The timid Sophia turned gay socialite caught the eye of many, including the Prince of Wales (the future George IV). In fact, both the Prince and the artist coveted Mrs Musters so much that they hung portraits of her in their private chambers.

Euphrosyne was a lesser-known divine figure, one of the Three Graces and the goddess of good cheer. This allegorical portrait of Mrs Hale, also by Reynolds, shows her surrounded by youthful figures in a celebration of music. Her bare feet, dressed in Greek-style sandals peek from beneath her gown. Very little is known about Mrs Hale (née Mary Chaloner), except that she had 21 children. Apparently, she was still able to dance with joy despite her heavy maternal responsibilities.

Mrs Hale as Euphrosyne

c.1762–1764, oil on canvas by Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792)

There can be no doubt that many goddess portraits were a celebration of the great and the good in an attempt to maintain the status quo in times of social upheaval. Women from the aristocracy were celebrated as symbols of the superiority of European civilisation. However, we also see expressions of societal change, involving scandal and glamour.

Henriette of France as Flora

1742, oil on canvas by Jean-Marc Nattier (1685–1766)

A contemporary goddess could freely show her playful, sensual side, not something normally seen in a traditional portrait. Just like cosplay today, a woman could explore notions of identity and autonomy. She could relish her appetites and accomplishments, and display her wit and intelligence. And that is definitely something to celebrate!

Candy Bedworth, writer

This content was supported by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation