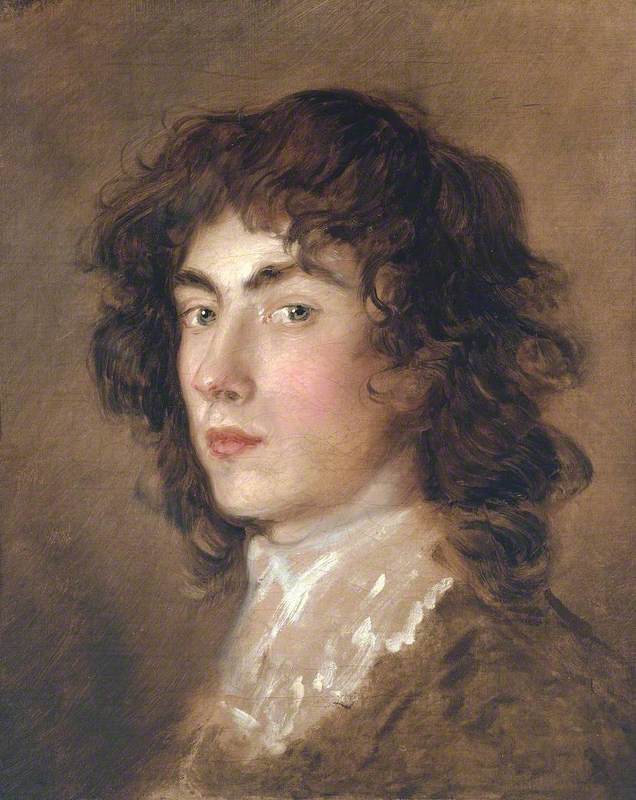

Johann Zoffany was born in Frankfurt in 1733. He received his training first in Regensburg, where his father was a court architect and cabinet-maker, and later in Rome. He moved to London in 1758 – his self portrait, now in the National Portrait Gallery, was painted shortly after his arrival. Speaking little English, he was obliged initially to take work decorating clockfaces. One of his earliest patrons in England was the actor David Garrick.

David Garrick as Sir John Brute in Vanbrugh's 'The Provoked Wife'

1763–1765

Johann Zoffany (1733–1810)

Zoffany painted a number of portraits of Garrick, both alone and with his family, as well as in character – as in David Garrick as Sir John Brute in Varbrugh’s ‘The Provoked Wife’. It was through these works that Zoffany came to the attention of the wider public.

Zoffany enjoyed immense popularity with the era’s emerging middle class. His detailed ‘conversation pieces’ could be set in luxurious interiors or in the grounds of expansive country estates. They often included props, such as reproductions of recognisable works of art or musical instruments. They were the perfect medium through which prosperous families could confirm their place among England’s elite, while demonstrating their refinement and wealth.

The Woodley Family, for example, in the National Trust’s collection, depicts the family of William Woodley and was painted shortly after William became Governor of the Leeward Islands in the West Indies. The family appears in fine clothes, at the edge of a forest, posed around a replica of the Medici Vase.

Another fine work from this period is The Family of Sir William Young in the collection of National Museums Liverpool.

With the subjects posed on the edge of a broad landscape, with stone steps, and a portico just visible to the right, the composition is able to indicate the family’s possession of two key status symbols: land and a country house. William Young had, like Woodley, made his fortune in the West Indies. His large family is shown in theatrical ‘Van Dyck’ costume, a very fashionable motif for portraits of the time. At the centre, Sir William, his wife and an elder daughter are engaged in a musical recital, while, to the left, a black servant helps a younger son onto a horse. Every element of the composition is geared towards creating an atmosphere of wealth, good taste and familial harmony.

Zoffany’s Garrick portraits had also brought him to the attention of George III’s German wife, Queen Charlotte, who became his patron. He painted several portraits of the Queen with her children and it was from her that he received the commission for one of his most famous works.

Zoffany spent five years working on the Tribuna of the Uffizi, a painting of the Tribuna room of the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. In it are painstaking reproductions of old master paintings, sculpture and classical antiquities. In addition to the artworks, however, the Tribuna is crowded with recognisable British figures in Florence at that time – including a portrait of the artist himself. At the time the inclusion of these figures in the work was considered a gross misjudgment on Zoffany’s part. Queen Charlotte, according to George III, ‘would not suffer the painting to be placed in any of her apartments’. It was the last commission Zoffany received from the royal family.

After falling out of favour with the Queen and with the fashion for his trademark conversation pieces dwindling, Zoffany became convinced he could revive his fortunes in India; he landed in Calcutta in 1783.

Colonel Mordaunt’s Cock Match in the Tate collection is a key work from the time Zoffany spent in India. It was originally commissioned by the Governor-General of Bengal, Warren Hastings, and depicts a real event at which both Hastings and Zoffany were present. The stunningly detailed and busy scene shows a cock fight between Asaf-ud-Daula, Nawab Wazir of Oudh, and Colonel John Mordaunt, the British commander of his bodyguard.

The painting is evidence of the extent to which the British and European officials mingled with native courts on relatively equal terms. Mordaunt stands centre left in white; facing him, in gold trousers and an opaque tunic is the Nawab. They are joined by an enormous cast of Indian and European onlookers, Zoffany even includes himself here, seated in white towards the top right.

Zoffany returned to England in 1789, by which time his abilities were noticeably diminished. He continued to paint, but exhibited at the Royal Academy for the last time in 1800 and died in 1810.

Adam Jackman, Freelance Editorial Consultant