When Charles III became King of the United Kingdom in 2022, he bestowed on his eldest son William and daughter-in-law Catherine the titles of Prince and Princess of Wales. This tradition of giving the title to the English (and now British) heir apparent, which is today contested by many in Wales, dates back to 1301 when Edward I (1239–1307) granted the title to his son to mark his – and therefore England's – final conquest of Wales.

Edward I Presents the First Prince of Wales to the Welsh Chieftains at Carnarvon, AD 1284

John Gilbert (1817–1897) (copy of)

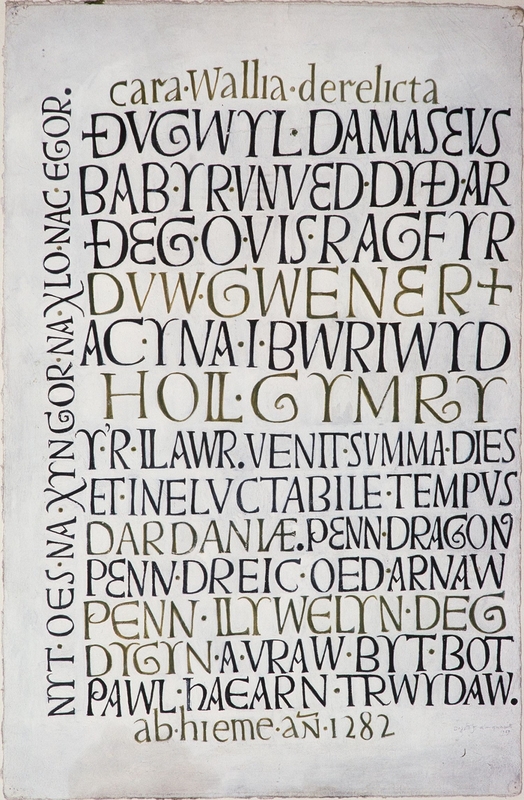

This act resulted in Llywelyn ap Gruffudd (1220–1282), the prince of Gwynedd in northern Wales who repeatedly sought to protect Welsh territory from English invasion, being the last native-born Prince of Wales, with his daughter Gwenllian (1282–1337) the last native Princess. Her mother, Eleanor de Montfort, died in childbirth and when her father died in battle against King Edward's army in 1282, a few months after her birth, Gwenllian was placed in a convent without freedom where she remained until her death in 1337. As the heiress of Llywelyn, she was regarded as a threat to the Crown by the English rulers.

Given that Llywelyn and Gwenllian lived prior to the period of conventional portrait making, all that exists to visually commemorate them and what they represent are monuments, such as the understated Gwenllian Memorial on Castle Road, Kidwelly, Carmarthenshire, or fanciful depictions such as the statue of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd in Cardiff City Hall. A memorial to Llywelyn was also erected in 1956 in Climeri village, Powys, to commemorate the site of his death.

Having the nation's last recognised native Prince standing at the top of Cardiff City Hall's red-carpeted staircase sends a clear message. Namely, that this centre of local government is committed to protecting the interests of the Welsh people within the United Kingdom.

Statue of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd (c.1223–1282) in Cardiff City Hall

1913, sculpture by Henry Alfred Pegram (1862–1937)

With a classical aesthetic and a form reminiscent of representations of David and Goliath, the sculpture begs those within City Hall to think and act heroically for Wales. This sentiment underlines the importance of Llywelyn ap Gruffudd to the nation – he represents Welsh strength and autonomy.

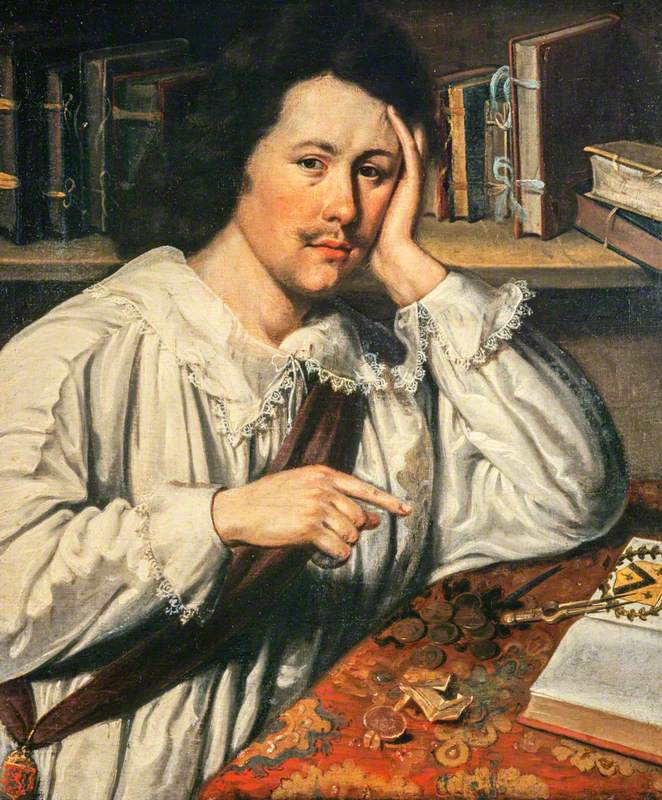

Edward I's political act of granting the Prince of Wales title to the heir apparent means that most historical images of 'the Prince of Wales' are portraits of children. Henry, Prince of Wales (c.1603) by Marcus Gheeraerts the younger (1561/1562–1635/1636) is an example of this trend. In this work, the Prince – a pale slender boy aged around nine – wears the robes of the Order of the Garter. On his small frame, these mighty robes appear comical to the contemporary viewer.

However, the purpose of this depiction would have been to bestow chivalric honour onto the young Prince. On one hand, the monumental meaning of this honour conveys how close the Crown holds Wales to its identity, and on the other, it forces the point to the Welsh people that Wales is secondary – their Prince can be an English (or in Henry's case Scottish-born) child.

A second painting that reiterates the two themes of holding Wales close to the Crown, while infantilising the nation at the same time, is Charles I and His Eldest Son, Charles, Prince of Wales. In this work, King Charles sits on a throne with the younger Charles (later Charles II) at his knee. The younger Charles timidly points a little finger up at his father.

This gesture conveys to the viewer that one day he will take his father's place, which is reinforced by the placement of the sceptre on the table that points directly at the future king. Beside the sceptre lies the crown which is also strategically placed under a distant depiction of Parliament House. This positioning alludes to the future responsibilities of the child Prince as ruler of all the subjects of the United Kingdom.

One of the most interesting examples of this motif takes the form of a group portrait of Henry VII, Queen Elizabeth (of York), Henry VIII, Queen Jane Seymour, and Edward VI, as Prince of Wales. This painting dates from 1699 yet was based on an original (now lost) work from around the 1540s by Hans Holbein the younger (c.1497–1543). The original work was commissioned by Henry VIII to mark the Acts of Union between 1535 and 1543 which linked Wales inseparably with England.

The hugely significant 1535 Act (which was ratified in 1536) directed 'for laws and justice to be administered in Wales in like form as it is in this realm', and the later Act of 1543 contained further details about what that meant – just in case there were any doubts. The acts had an especially detrimental effect on the Welsh language as from this point English was to be the country's first language – Welsh-speakers were no longer to receive public office.

Placing the Prince of Wales front and centre within this family portrait, with the Tudor arms, supported by the English Lion and Wales's Red Dragon, right above his head can be read as a celebration of unity, but it also evokes a symbolic statement of authority. Wales, here, is literally surrounded by English rulers. Once again, Wales is depicted at the heart of the Union, but it is secondary to England within the partnership.

Over time, the trend of depicting young Princes of Wales in a controlling visual manner passed. Despite this, propagandistic undertones still infiltrated depictions of the Prince of Wales. For example, in Thomas Roland Rathmell's work from 1969–1970 depicting the investiture of Prince Charles, the artist chose a viewpoint which emphasised the volume of spectators more than the actual act of the investiture. With the viewpoint being so far removed from the seating area of the actual event, it echoes the experience of watching on television, so that the work seems to reference the numerous people watching at home.

The Investiture of Charles III (b.1948) as Prince of Wales, July 1969

1969–1970

Thomas Roland Rathmell (1912–1990)

It is important to note that this painting was commissioned by the Welsh Office – a UK government department responsible for Wales established in 1965 to execute government policy in the nation. At the time, this office would have wanted a painting that accentuated the importance of the work that they were doing – administering Wales within a settled Union.

While for many, Wales's complex relationship with the Crown remains a thorny issue, for some it eased in more recent history thanks to the personality and celebrity of Diana, Princess of Wales. Of the 11 women to have held this title since the fourteenth century, Diana, the first wife of Charles III, is the most famous – even when that list includes Catherine of Aragon, a portrait of whom is in the collection of the National Museum of Wales.

The good that Diana did – and seemed to embody – resulted for some in Welsh pride by association. This sentiment is palpable in the portrait of Diana hanging in Cardiff City Hall.

Here, Diana is depicted in three different poses and, in my mind, the work emulates a well-known portrait depicting Charles I by Anthony van Dyck.

The apparent mimicry of a famous portrait of an infamous English king to portray Wales's Princess – located in the central administrative office of Wales's capital – could be read as a sign that many in Wales welcomed Diana representing them on the global stage. Others will, however, feel much more ambivalent about such a portrait and what it says about Wales's relationship with the British Crown.

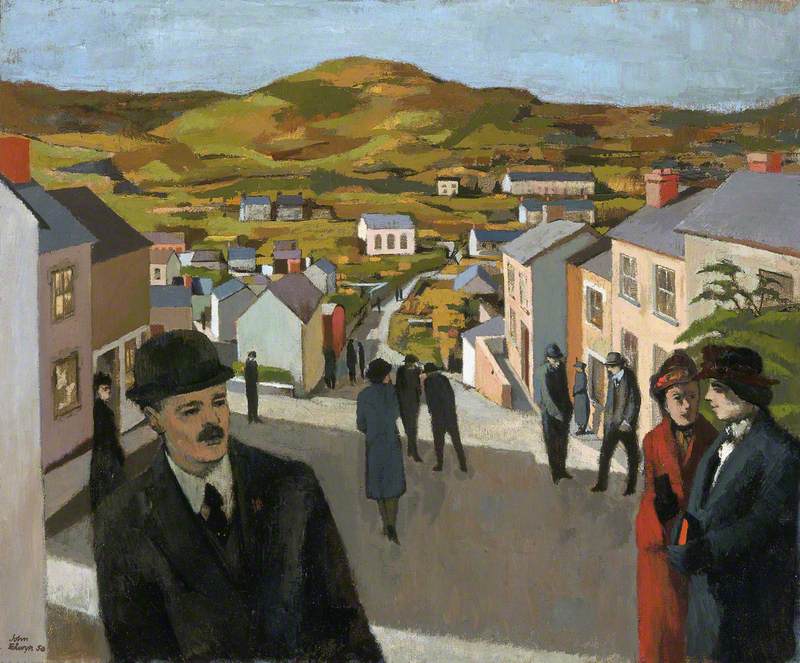

As the Welsh have come to reassess their identity more, representations of a 'Prince of Wales' from within the nation have largely taken the form of public works. One example is the statue of Owain Glyndŵr (c.1354–c.1416) in the square at Corwen, Denbighshire.

Owain Glyndwr (c.1349–c.1416)

2007

Colin Spofforth (b.1963)

In 1400, Glyndŵr, who was descended from Welsh royal dynasties, had a dispute with a neighbouring English lord that resulted in him claiming the title of Prince of Wales and instigating a revolt against English rule under Henry IV. As we know, this revolution was not a success. Although the statue may not essentially represent a literal battle call for Welsh independence, its selection and town centre placement underline that Wales is in the process of reassessing what defines it as a nation.

Wales's relationship with the Crown continues to be a topic of debate, which the current Prince and Princess of Wales, William and Catherine, are having to navigate. There has been sensitivity towards Welsh national identity – including from prominent figures such as actor Michael Sheen – that acknowledges the current mixed feelings regarding the title of Prince of Wales and what it represents. This sentiment is observed by the fact that there has been no investiture for William, nor is it seemingly on the cards.

The first official royal portrait of Princess Catherine, unveiled in 2012, shows her poised and confident, and symbolises a new era of royal representation. Her image exudes a sense of duty and readiness to embrace the complexities of modern leadership. The implication is that she is up to the task of navigating a multitude of contemporary concerns – with Wales's future relationship with the Crown being just one of those.

Fern Insh, art historian and arts engagement specialist

This content was funded by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation