Let's analyse pictorial composition by concentrating on the structure of bridges as represented by painters who create the illusion of form within the traditionally accepted confines of the picture plane.

Painters depict scenarios that satisfy their own desire to make paintings that tell their own story of interpreting the world. Each artist has an innate style that offers a way in to looking at their art. Here we look at bridges that are the compositional force within these paintings and show off the style of each artist.

Bridges connect places: two sides of a river, a valley, roads or even two countries. In art, bridges are a very good excuse to do paintings of repeated architectural shapes related to water, cities, towns, or expanses of space, of the activity of crossing and being on the move or of people and objects being on the water.

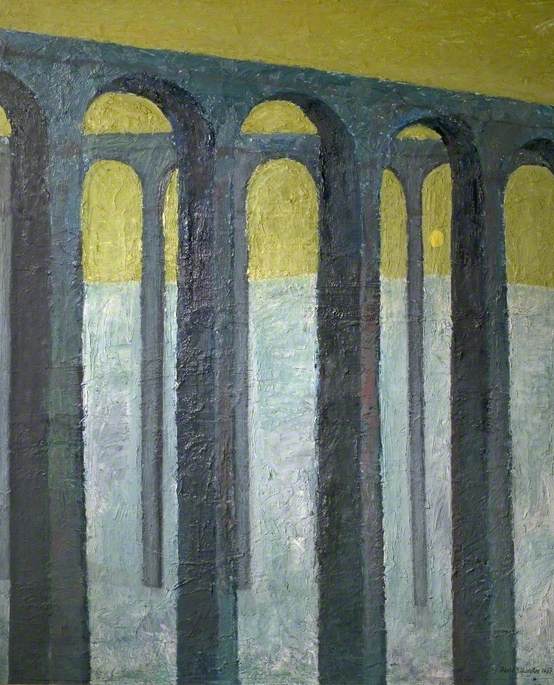

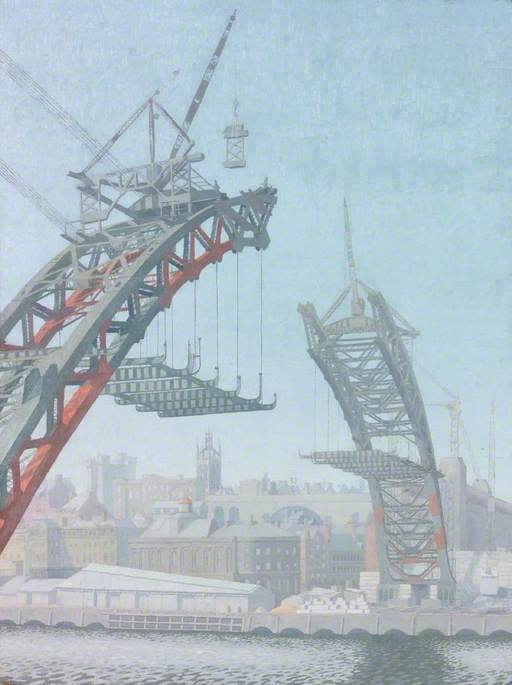

The first three examples focus on abstract views with minimal colour. This means that our attention is directed towards the form and shape of the bridge itself. All three paintings are portrait (vertical) shaped canvases and deal only with the elegance of thin columns or struts and metal ironwork.

In David Pilkington's Bridges, from 1955, cool grey columns almost float within a field of pale white grey and the 'sky' he paints is a pure lemon yellow.

If it were not for the curved tops to the grey spines that echo the shape of the vertical canvas, we could view this as a purely abstract painting.

That Edward Montgomery O'Rorke Dickey depicts a bridge under construction adds another layer of interest for the viewer, as we know that the artist is himself constructing his own picture.

If you are painting a picture of a bridge, you must decide on the angle of your bridge and this will determine other factors such as figuration or abstraction but more importantly, areas of colour and where light and dark parts will occur.

Looking carefully at these three images the details show the darkest parts and how these reinforce the rhythm of the internal picture dynamic. These dark areas mobilise the picture surface with the effect that it can appear to move in front of your eyes. Repeating shapes (like bridges) encourages this phenomenon.

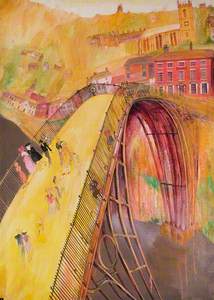

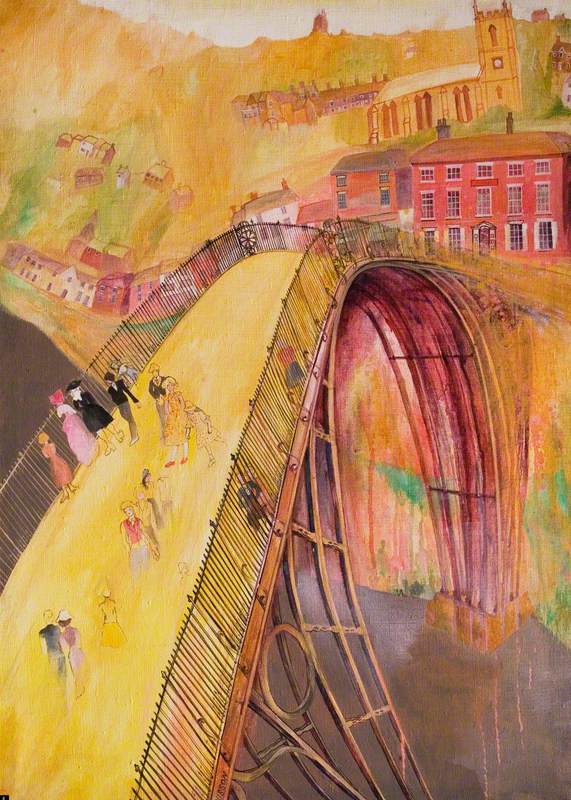

Barbara Mary Russon's bridge spans not only space but time.

© the artist's estate. Image credit: Herbert Art Gallery & Museum

Ironbridge, Shropshire: Visitors Past and Present 1960s–1980s

Barbara Mary Russon (1930–2007)

Herbert Art Gallery & MuseumThose wandering over its high arch are shown in both contemporary and period clothing turning the picture into some kind of dreamscape. This sensation is enhanced by the way that the artist uses the drift in the paint itself and the crazy warp of the arch recalls the distortions that can occur during the unfolding of dream stories.

It is a lyrical view also grounded within the specific depiction of recognisable local Ironbirdge buildings including the church. The patterning of the wrought iron railings is delicate and almost musical in its stave-like appearance.

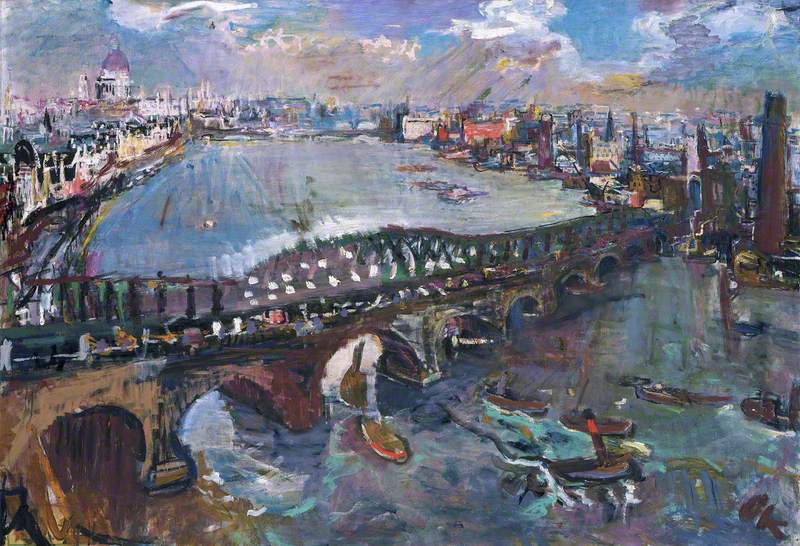

Bridges are great subjects for painting as they provide a series of repeated dark and light shapes naturally. Arches contribute rhythm as we can appreciate in Kerry James Marshall's bridge painting showing a hive of human riverbank activity.

However, it is the bridge that underpins the whole of the action compositionally and places us in central London. Those particular light-coloured grey arches traversing the painting echo the movement of the people and offer a context for the narrative.

We recognise the specific lights above the placard that states 'London Bridge' and there is a red bus crossing and someone in the foreground who is in quasi-guards uniform who seems to be carrying a sandwich board advertising fish and chips. There is another placard with an image of Queen Victoria.

Look more closely and American flags appear alongside the Union Jack, and why are palm trees growing in London?

This conundrum is offered to us by the artist who is enjoying the ambivalence of the scene – yes there are pigeons and tourists, but are we really in London? This is a painting of the London Bridge that was sold to an enterprising American Robert P. McCulloch, who reinstalled it in 1971, in Lake Havasu City, Arizona.

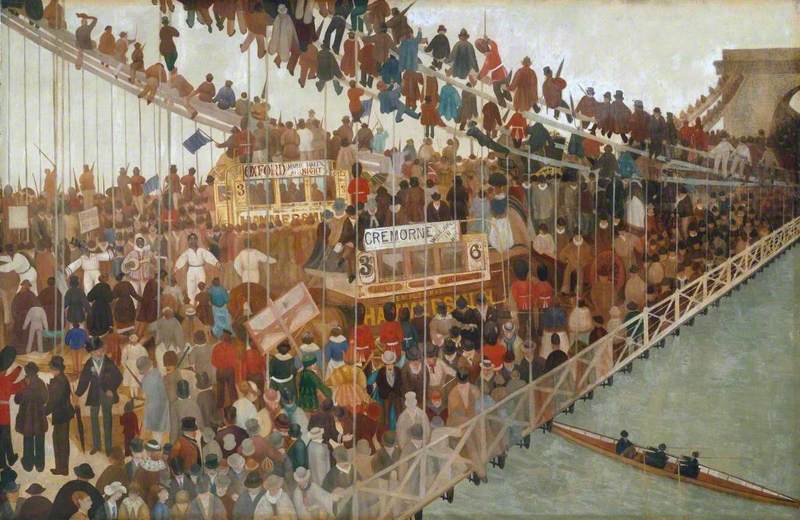

There is something about the Marshall painting from 2017 that chimes with Walter Greaves's Hammersmith Bridge on Boat-race Day, painted in around 1862, although 155 years separate them.

Greaves paints a picture of people as bridge decoration, focusing on their physical connection to the bridge: they are crowded all over it so that they can enjoy looking at all the decorations and celebrations that surround the boat race between Oxford and Cambridge universities.

The painting is organised around diagonals forming three main areas. A scull with three rowers fits into and bisects the bottom right grey river triangle, while above more triangles appear outlining the shape of the first suspension bridge ever built over the Thames.

Like Marshall's, Greaves's busy bridge also has military guards in bearskin hats who are here in a more official capacity, there are also flags, placards and advertising. The crowds seated on the steel trusses appear like three-dimensional bunting – mainly men, many wear hats; some bowler and some top. At the centre left is a troupe of five performers with the banjo player in fancy dress. Near to this are two constructions (or a repurposed bus?) creating platforms for more capacity.

Bridges that we might consider to be permanent, stable and fixed are in fact quite flexible and can be rebuilt, moved or replaced. The compositional anchor of the bridge structure can be exploited pictorially in different ways.

Walter Greaves's friendship with James Abbott McNeil Whistler emerged from their teacher-pupil/studio assistant relationship. Whistler's memorable paintings of the Thames stand out as semi-abstract interpretations of the mood of the river.

'Nocturnes', as he called them, suggest a very different atmosphere from the boat race day and introduce the feeling of music that wafts up from the shifting grey-blue surface of the water at dusk.

Image credit: Tate

Nocturne: Blue and Gold - Old Battersea Bridge c.1872–5

James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834–1903)

TateWhistler uses the shape of the tall, serene and elegant Battersea Bridge, rising up out of the mists to dominate his work. The structure looms out at us like some great behemoth, its long legs, astride the slow, dim waters.

This is a breakthrough painting that embodies his desire for a new type of image. Grounded in his appreciation of Japanese art, influences that he absorbed during his time in Paris are fully expressed within this magical painting. Even the people crossing the bridge in the half-light seem to shuffle along – their colour melds them into the actual structure as it arches over the river. The lonely boatman creates a picturesque silhouette and we sense the outline of the opposite bank more than recognise it. Fireworks trail and shower in the sky liaising with the twinkle of pinpoints of light in the middle distance.

This poetic image has now gathered such status and familiarity through multiple reproductions that it has an energy of its own. It would be hard to consider Pilkington's columnar bridge without Whistler's example, and this atmospheric work brought a whole new dynamic to the artistic table.

People talk about building bridges as a metaphor for coming together. Building actual bridges requires engineers and designers, experts who can calculate the pressures involved in the construction of complex man-made structures. Portraying a bridge with paint is a parallel juggle of design and calculation although only within the confines of two dimensions.

If we look at examples of bridges in works by seventeenth-century artist friends Claude Lorrain and Herman van Swanevelt we experience the perfect Italian classical landscape – gentle hills, blue background mountains, strategically placed people and honey-coloured buildings, rocks, beautiful trees and the requisite curvy bridge.

Image credit: Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales

Landscape with Saint Philip Baptising the Eunuch 1678

Claude Lorrain (1604–1682)

Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum WalesThe paintings' compositional ingredients are often repeated with a beautiful mix of gentle colours, invoking cloud-studded skies and warm, undulating, fecund earth. This way of seeing bridges, as an important adjunct part of a whole picture, became the standard.

In the eighteenth century, this type of idyllic vista came to influence the way that landscape gardeners such as Capability Brown would reconstruct parkland owned by rich British landlords of great country houses. Bridges became standard additions too, even though many were purely decorative.

Canaletto's Walton Bridge is a purely wooden construct, as intricate as lace, completed in 1750 but dismantled in 1783.

The bridge seems to vibrate and glow due to front lighting but is made brighter because of the grey-mauve clouds behind it, and black shadows under the arches.

Unusually for Canaletto, real people are depicted – Thomas Hollis (the painting commissioner), his servant Francesco Giovanni and his dog, Malta, and to his right Hollis's friend and heir, Thomas Brand. The artist himself can be seen to the right of the cow, seated and at work.

It is a charming scene that blends the romance of Italian classical landscape with the more suburban Surrey setting. The work also celebrates the feat of engineering and bridge design by William Etheridge (1708–1776), known as a mathematical bridge.

In the nineteenth century, the Industrial Revolution facilitated the manufacture of bridges made of steel and iron that created an altogether different impact on the land, and this is reflected in the art that records them. These metal bridges offer a different visual dynamic as their construction material and methods behave in a different fashion that heralds a new world.

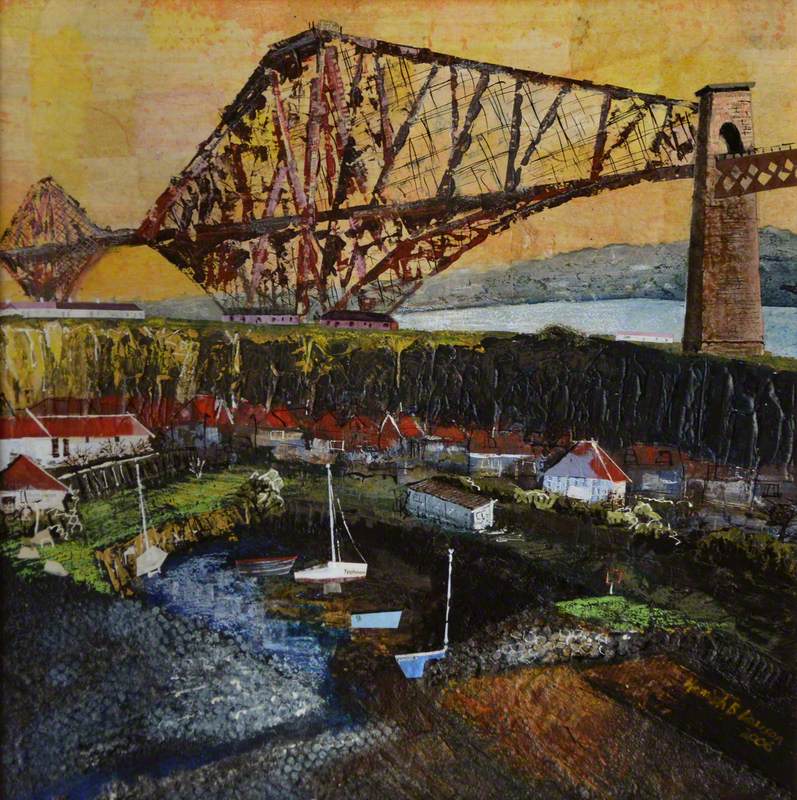

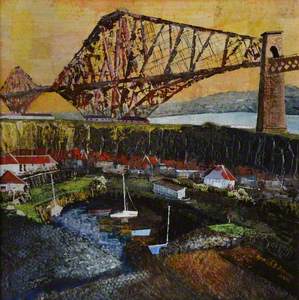

Metal bridges also open up the possibility of abstract painting. The bridge itself vies to become the subject rather than an object that is subjugated within the landscape. Hamish B. Lawson's North Queensferry depicts the Forth Rail Bridge.

Made of steel and opened in 1890, this iconic Scottish cantilever bridge is a World Heritage site. Like Whistler's Battersea Bridge Nocturne, a tracery of blood-red reflected forms dwarfs the red-roofed houses below. The artist's perspective is from slightly below the bridge but looking down on the boats and houses, while the beast of the bridge dominates.

Jock McFadyen's Coventry Girl Motorway Bridge records the industrial urban landscape.

Unlike the domineering Forth Bridge, this motorway crossing supports the figure in the elevated scene. The protagonist wears a Union Jack badge pinned to her open coat, a shoulder bag, a short-belted skirt and blue high heels.

She bestrides litter and leans nonchalantly on the metal railings staring out at us, her dark hair in strands against the pale blue sky as it blows in the wind. Below her a car park, and behind her a series of four great cooling towers still active with flames shooting up – symbols of a bygone era.

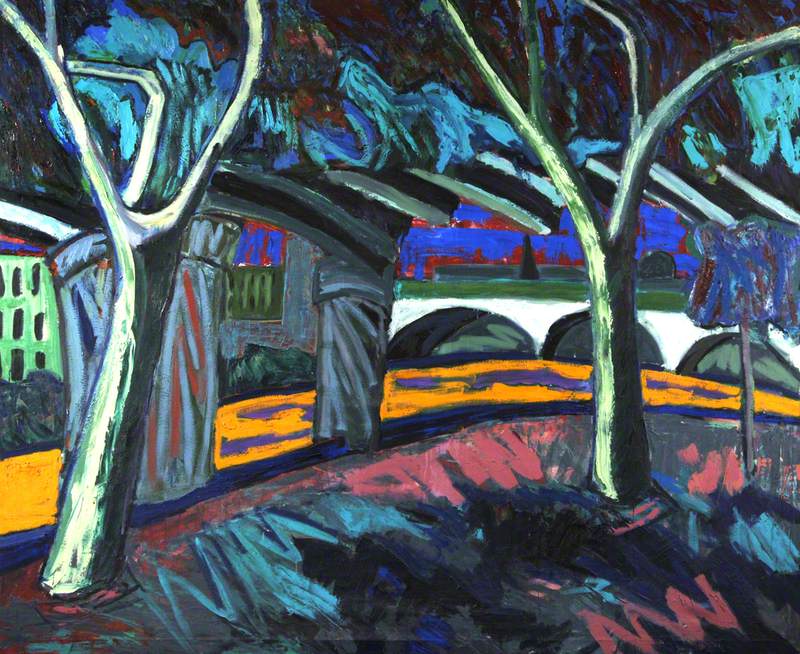

Lucy Jones's jazzy River Bank is in fact London's Southbank – and she evokes its bustle through black shadow, light and colour. The sharp acidic tints suggest an energy related to this cultural venue and the Jubilee walkway.

The viewpoint is taken from the underside span of the Hungerford Bridge (the Charing Cross train bridge) – highlighted in turquoise, skeletal white trees frame the scene and in the distance is the elegant white span of Sir Giles Gilbert Scott's Waterloo Bridge, opened in 1945. This bridge is also known as the Ladies' Bridge, having been largely built by a female labour force during the Second World War. Monet was just one of many artists who painted this bridge in both its first and second incarnations.

Jones's painting employs the dynamic of black and white to encase the orange-coloured water in a visual tango with a bright pink pavement.

The repeated white shapes of Waterloo Bridge are in a parallel dynamic with Leonard Gray's painting Two Bridges.

This final work within this series of painted bridges is a semi-abstract concentrated meditation on the dynamic of space. In this restrained work, we step back to judge and step away from the social intricacies of the bridge, to contemplate pure form and design.

This work has a calm clarity and poise, seeming to compare the qualities of one bridge against another and balance their similarities. There is no conflict in this alignment of shapes – the artist presents a double visual mantra: pale, low-key, linear, more in tune with De Chirico and Surrealism than the practicalities of getting from one side to the other.

As we reach the other side of our survey, we can see that by analysing the arcs, lines and tracery on the structure of bridges, we can understand how artists have created the illusion of form through bridges as compositional anchors.

Liz Rideal, artist and writer

This content was supported by Freelands Foundation as part of The Superpower of Looking