Once believed to be the 'tears of the sun' by the Incas, gold has always been one of the most universally treasured metals.

Found in objects from cultures all over the world, the insatiable appetite for gold was so great that it brought about the demise of entire civilisations.

Desirable for its unique luminosity and rarity, gold is still the bedrock of our wealth and economies. The metal's malleability and brilliant colour has interested and captivated artists for millennia.

Image credit: National Trust Images

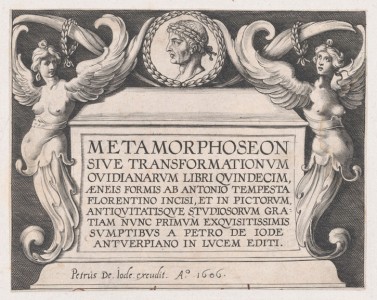

Marchesa Maria Serra Pallavicino (?) 1606

Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640)

National Trust, Kingston LacyFrom the Greek myth of the Golden Fleece to the legend of El Dorado (the 'golden city' or 'golden one'), ancient narratives about the material have persisted into modernity, cementing the idea of gold as a potent symbol of authority, sacred power and prosperity.

Due to the Christian spiritual and religious connotations of gold, the colour has become synonymous with the festivities of Christmas, reminding us of the Nativity, wherein gold was presented as a gift to the infant Christ.

Let's dive into the historical iconology of gold as a material laden with symbolic significance.

The ancient world

Gold was used widely across the ancient world, from the first civilisations of Mesopotamia, Egypt and India to the classical world of ancient Greece and Rome.

If not used in pure form, gold was typically gilded onto other metals such as bronze. Believed to have magical properties, it was often used as a talisman for the living, or buried with the dead to take to the afterlife.

For example, in ancient Egypt, gold was known as the 'flesh of the gods'. The material was used for all kinds of daily objects and ceremonial rituals.

Image credit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Gold statuette of Amun

Third Intermediate Period, 22nd Dynasty, c.945–712 BC, possibly from Thebes, Karnak, Egypt

Exalted as a symbol of immortality, the alluring metal was used by the ancient Egyptians to decorate the tombs of pharaohs. Gold was also buried inside the sarcophagi of the dead, alongside the preserved mummies.

Image credit: Shipley Art Gallery

Croesus Showing Solon His Riches c.1655

Casper Casteleyn (active c.1653–1660) (attributed to)

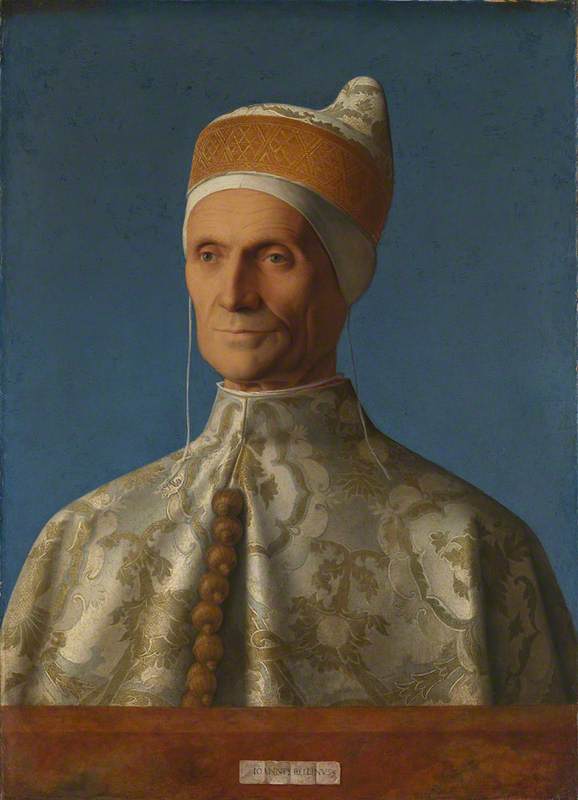

Shipley Art GalleryThe phrase 'as rich as Croesus' derives from Croesus, king of Lydia (now in western Turkey) who ruled around 560–546 BC.

Under Croesus, gold coinage began to emerge as a form of standardised currency. According to myth, the Lydian gold came from the river in which King Midas bathed – the water washed away his ability to turn everything he touched into gold.

Image credit: British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Gold coin of Croesus (reigned c.560–547 BC)

Minted in Lydia (now in modern Turkey)

When gold wasn't available, other materials and pigments were used.

Orpiment, a highly toxic mineral (arsenic) was used in the ancient world as it closely resembled gold. The Romans allowed slave labour to mine it, even if it resulted in deaths.

Though gold was unanimously valued across many empires, in ancient China, jade and bronze were more treasured. While gold was a symbol of excellence, jade was reserved for the most important amulets, ceremonial weapons and ornaments.

Byzantine and early Christian art

Though many gold or gilded objects survived the test of time, artefacts were often melted down or looted by successive civilisations.

During the Byzantine Empire and the early centuries of Christianity, gold was frequently used to symbolise transcendent, divine light embodying the invisible, spiritual world.

Image credit: The National Gallery, London

The Virgin and Child about 1265-75

Master of the Clarisse Panel (active 1275–1300) (attributed to)

The National Gallery, LondonGold could be found in the background of icons, mosaics, triptych panels and architectural settings.

Ancient manuscripts

Illuminated manuscripts from the early Christian and medieval eras typically used precious gold leaf to embellish important books. Gold was also typically used to illuminate manuscripts beyond just European art history, as it can be found in Islamic manuscripts.

Image credit: The British Library, London

Haggadah for Passover (the 'Golden Haggadah')

c.1320–1330, illuminated manuscript from Spain and Italy

Another example from Europe is the Golden Hagaddah (c.1320–1330), a luxurious work of art which narrated the Passover text through 56 miniatures (small paintings). This book was most likely owned by a wealthy Jewish family in fourteenth-century Spain.

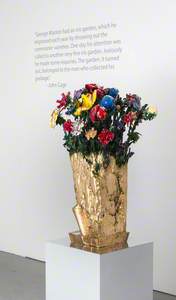

Persian, Indian and Mughal miniature painting

In various Islamic empires, there were rich traditions of using the colour gold in court painting. Royal patronage brought about the 'miniature', a mode of painting found across Persian, Mughal and Indian art history.

Due to the Islamic laws that prohibited the depiction of recognisable imagery or divine figures, artists spent hundreds of years developing calligraphy and embellishing their intricate paintings with exquisite detail inspired by geometry and the natural world.

Image credit: Victoria and Albert Museum

Akbar

18th C, opaque watercolour & gold on paper, by unknown artist

In particular, miniature painting flourished under the Mughal Emperor Akbar (1542–1605), who helped synthesise and establish an Indo-Persian artistic culture, of which miniature paintings flecked with gold leaf were at the centre.

Gold was generously used to adorn these meticulously designed miniatures: illuminating text, highlighting architectural structures, armour and clothing, or found in the decorative borders. Artisans would prepare a paint made out of finely powdered gold, which would be used on top of a special kind of gold-flecked vellum paper.

By the eighteenth century, the Mughal court was in decline, meaning fewer miniatures were produced by the royal workshops. With the advent of expanding British colonialism and the dominance of the East India Company (which later became the British Raj), Mughal miniatures were looted or transported to Europe.

Medieval and Renaissance Italy

Generous amounts of gold leaf were applied to paintings in thirteenth- and fourteenth-century Italy, during the end of the Middle Ages and the emergence of the Renaissance.

Image credit: The Fitzwilliam Museum

Virgin and Child (centre), Saint John the Baptist (left) Saint George or Saint Ansanus (right)

Filippo Lippi (c.1406–1469)

The Fitzwilliam MuseumBecause the Church was the most important patron of the arts, a demand for religious and divine subject matters provided the perfect context in which to use luminous gold – a pigment that could embody celestial, heavenly light, or the Holy Spirit.

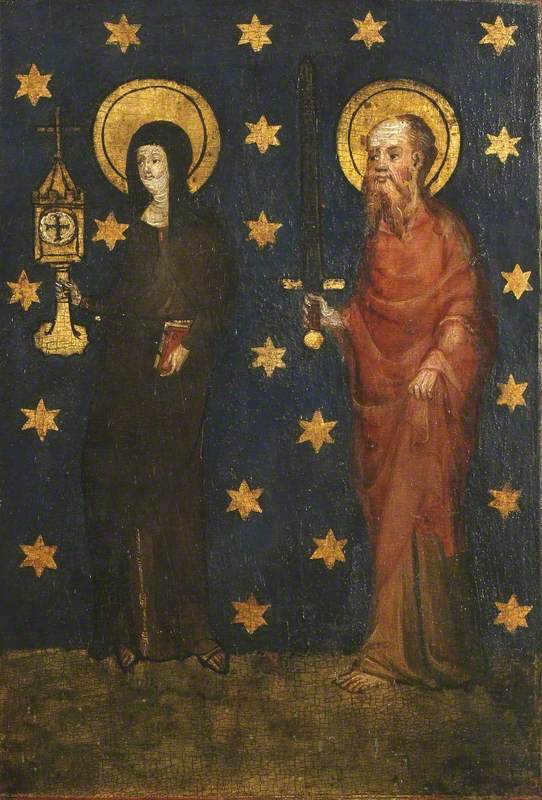

Among its many applications, gold leaf was used to illuminate architectural settings in the paintings of Giotto di Bondone, Duccio, Fra Angelico and Cimabue – gold-ground panel painting and altarpieces, and embellish the halos of divine, saintly figures.

To create gold panel painting was a lengthy process which involved many artisans – a special process called 'water-gilding' was used to apply thin gold-leaf to wooden panel paintings. The panel would then be burnished to create a glittering, brilliant surface.

In this exquisite painting by Alesso Baldovinetti (c.1426–1499), the woman's flaxen hair and golden dress are accentuated by the gold leaf of the painting's frame.

Modern times

In 1907, the Symbolist artist Gustav Klimt (1862–1918) completed his portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer, immortalising her in one of the most famous paintings of the twentieth century.

Created during Klimt's 'Golden phase', this painting is deemed to be an expression of desire and reverence.

Image credit: Belvedere, Vienna

The Kiss

1907–1908, oil on canvas by Gustav Klimt (1862–1918)

Klimt's obsession with gold lasted for nearly a decade and took place at the turn of the twentieth century.

Influenced by classical, Byzantine and Renaissance art, Klimt's golden works paid homage to many centuries of art history in which gold leaf was a commonly applied pigment. But his work also introduced an avant-garde Viennese style, referencing the Arts and Crafts Movement in Britain as well as the emergence of Art Nouveau (or Jugendstil, as it was called in Germany and Austria).

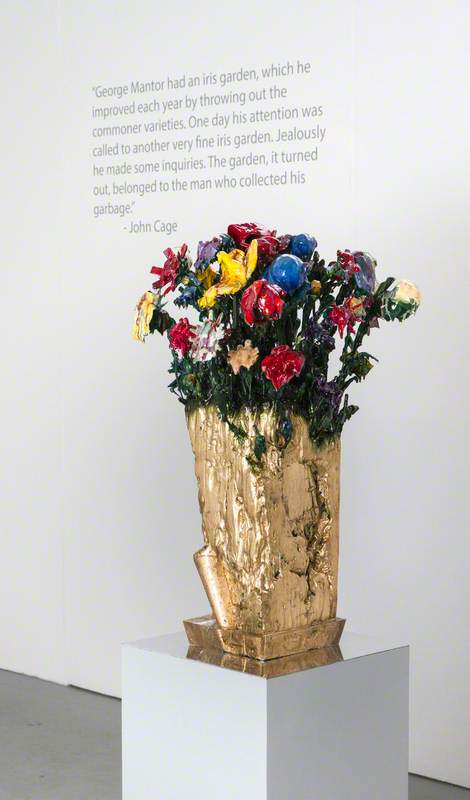

In contemporary culture, gold continues to convey a myriad of different meanings, and is typically still used to symbolise prosperity, fortune and success.

The symbolism of gold has been communicated across centuries and cultures. Its influential presence and psychology have been so great, the colour has transcended visual culture and entered our language: 'golden days', 'as good as gold', even 'fool's gold'...

In many ways, gold has shaped our world, as much as we have moulded it into our material culture.

Lydia Figes, Content Creator at Art UK