One of my favourite galleries out of the very many I have visited while writing about the history of art museums in Britain is the Lady Lever Art Gallery in Port Sunlight, near Liverpool. The Lady Lever was built as a memorial to his wife by the first Lord Leverhulme, who had made a fortune in soap and was a master of the growing advertising industry, on which he spent heavily. The gallery forms the centrepiece of a planned village built on paternalistic lines for Leverhulme’s work force. Leverhulme became a passionate collector, obsessed by buying works of art, and his gallery is one of those ‘collector museums’ that have a strong sense of individuality. I particularly like the sense of rich sumptuous enclosure that you experience as you walk through the building.

Leverhulme collected all sorts of things: French and English paintings and furniture, Napoleonic relics (Napoleon was one of his heroes), embroidery, Wedgwood and Chinese porcelain, embroidery, archaeological specimens and even Masonic relics (he became a passionate Mason in later life). They are housed in grand but not intimidating rooms and offer constant surprises as well as a sense of recognition.

Here are a few of my favourite works in the collection. They are all the kind of picture that Victorian audiences – and traditional collectors like Leverhulme – loved. They went badly out of fashion around 1900 but are now as popular as ever:

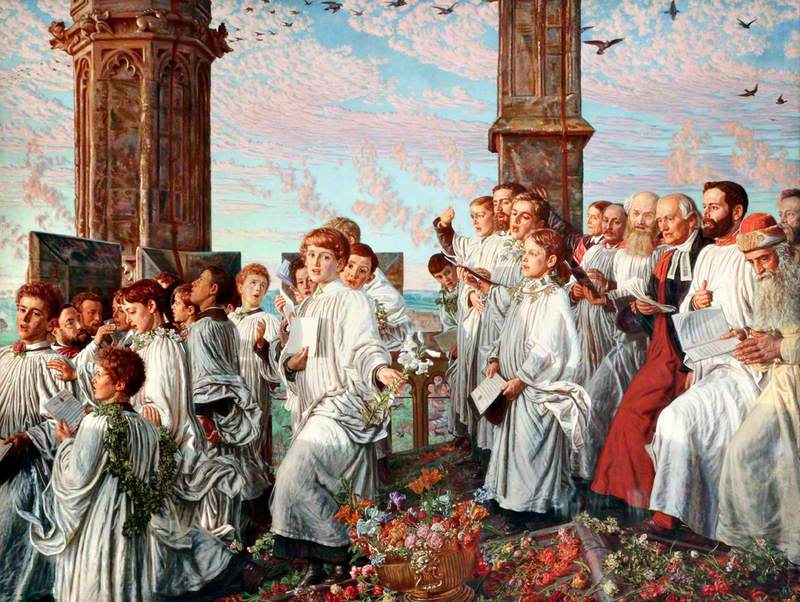

This glorious early summer event when the choir of Magdalen College Oxford celebrate May morning is still held even though today’s crowds are not always inspired by religious feelings. In his realistic yet strangely highly coloured painting Holman Hunt gives a vivid sense of the excitement of the early morning, suffused by light, into which the singing of the men and boys bursts.

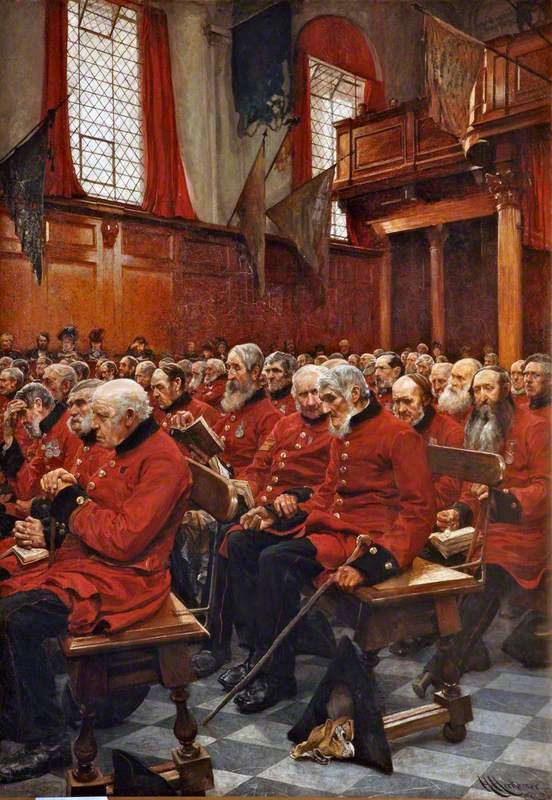

The Last Muster, Sunday at the Royal Hospital, Chelsea

1875

Hubert von Herkomer (1849–1914)

Herkomer was famous for his social realist paintings, depicting the lives of ordinary people, sometimes those living in institutions. This painting parallels his study of old women in a workhouse, Eventide: A Scene in the Westminster Union (Walker Art Gallery, Liverpool). Tender in its portrayal of the pensioners living in Chelsea Hospital, it contrasts their present condition with their warlike past in a way that would have appealed strongly to the audiences of his time.

Millais takes an imaginary episode of a young officer going off to battle, inspired by the events around the battle of Waterloo, when the regiment known as the Black Brunswickers fought bravely and suffered huge losses. As the girl tries to restrain him, her lover’s hand moves inexorably towards the door and departure. Millais contrasts the softness of the girl’s dress with the military darkness of the uniform. It is a bold and rather erotic image.

Giles Waterfield is author of The People’s Galleries: Art Museums and Exhibitions in Britain, 1800–1914, published by Yale University Press, 2015.