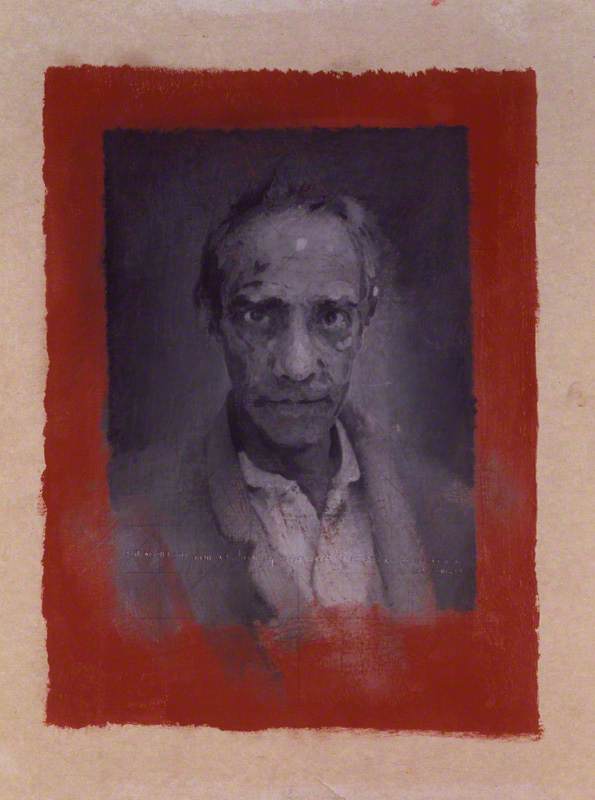

Born in Knowsley, near Liverpool, Christopher Wood was one of the most gifted artists of his generation. Following his suicide at Salisbury train station in 1930, the mystery that surrounded his untimely death aged just 29 has inevitably taken equal precedence alongside his achievement as a painter.

However, the magnitude of his creative ambition, which resulted in his rapid ascent both amongst the cultural milieu of Paris and the British art world, was an extraordinary aspect of his short career. A friend of Pablo Picasso and the painter-poet Jean Cocteau, he also forged a strong alliance with the artistic couple Ben and Winifred Nicholson, with whom he nurtured a self-consciously 'naive' figurative style that was highly influential among his contemporaries in Britain.

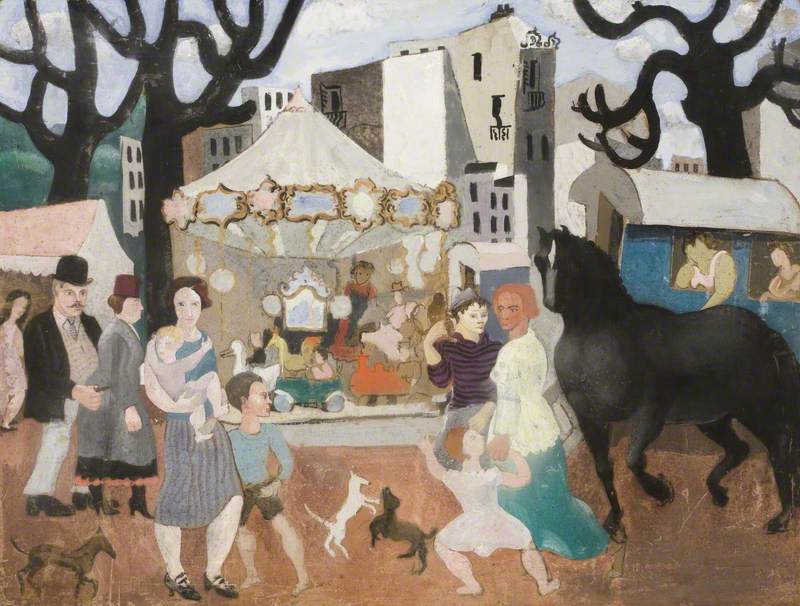

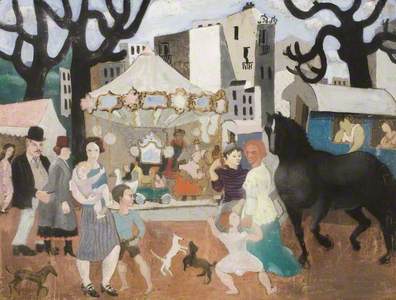

During the height of the 1920s it was Wood's art that stood in opposition to academic convention, eschewing aesthetic sophistication with a childlike directness that seemed to speak of a more inherent truth about the world.

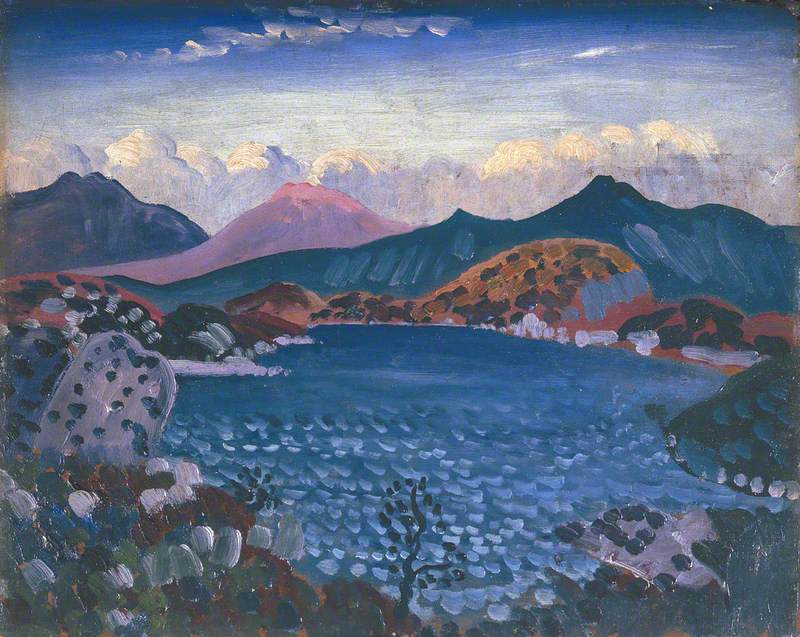

The exhibition at Pallant House Gallery will demonstrate that Wood's unique pictorial idiom developed through his personal response to the specific conceptions of 'primitive' art that were prevalent in both Britain and France during the 1920s. Arriving in Paris in 1921 at the age of just 20, to a large extent he was exposed to the fashion for artefacts from the Far East, Africa and America through its reference in Cubist and Fauvist painting. This in turn was manifested in his own work through his replication of gestural brushwork, decorative surface patterns and stylised, pared-down forms.

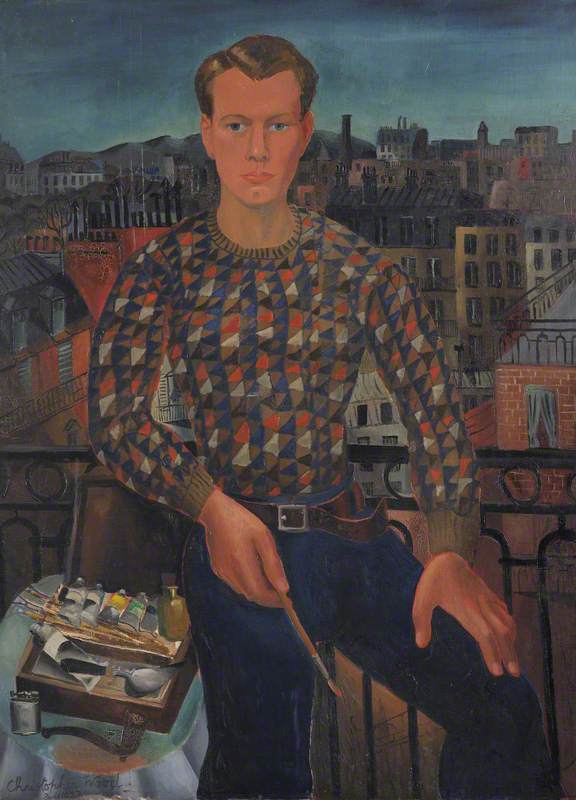

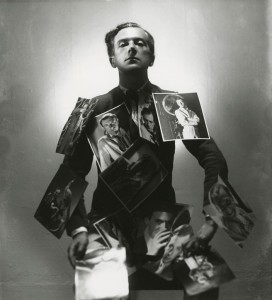

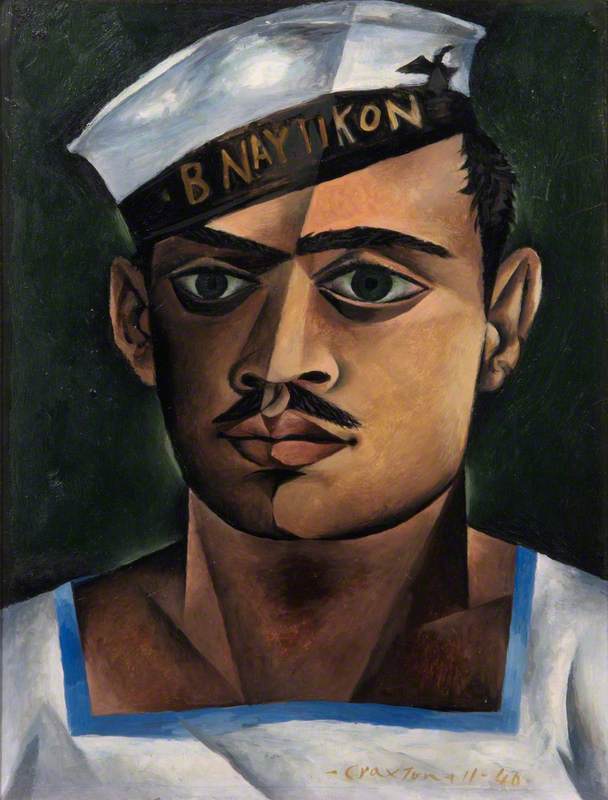

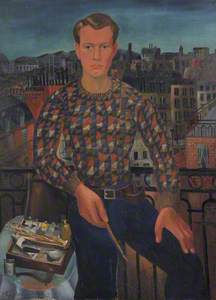

Meanwhile the candid mode of representation employed by the untrained painter Henri Rousseau can be found in the frontal, simplified presentation of Wood's portraits, including his immense self-image in a harlequin-patterned jumper painted in 1927. Having seen a painting by Rousseau in the studio of Picasso alongside African and Iberian carvings, Wood no doubt recognised that for many contemporary artists Rousseau's stylistic naivety was derived from the same 'primitive' mind that they attributed to the people of non-Western societies.

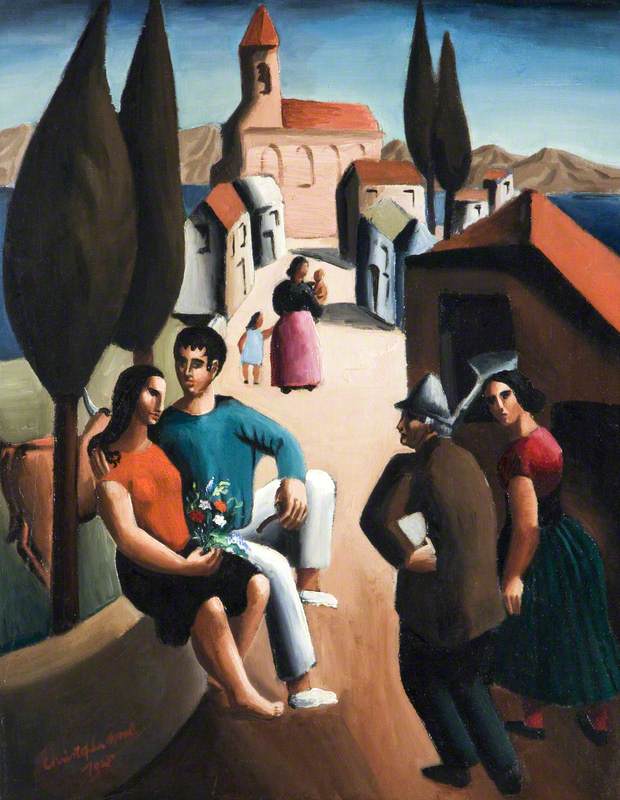

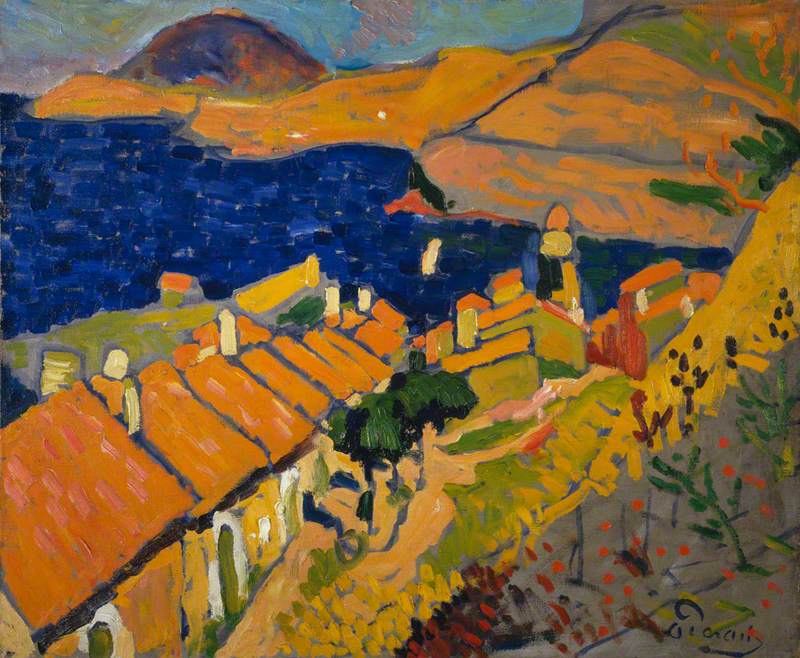

Further to this, the concept of retreating into these so-called 'savage' communities was also highly influential to the generation of modern painters that Wood encountered in Paris. Exemplified by Paul Gauguin in his trips to Brittany, Martinique and Tahiti, and to lesser extent Van Gogh in the peasant communities of Arles during the 1880s, the Post-Impressionists provided the template for how artists might harness aspects of the 'primitive' by escaping the trappings of their sophisticated milieu for a more profound ritualistic existence.

All of this was astutely understood by Wood. As early as 1922, less than a year after arriving in the French capital, he explained in a letter to his mother that most modern artists strove to interpret their subjects as though 'through the eyes of the smallest child who sees nothing except that which would strike them as being the most important'. The published letters of Van Gogh also had a huge impact, in particular the comparison he made between the solitary struggle of the artist and the hard-worn existence of rural peasants, who he felt were closer to nature and therefore less morally corrupt. Reflecting on the purity of Van Gogh's ideas, Wood commented to his mother: 'He must have had such a beautiful mind, so broad nothing petty could have entered his head, otherwise he could never have painted.'

For all the admiration that Wood bestowed on these modern masters, the ability to view the world through innocent eyes was a quality that artists and critics came to identify in his own paintings. In Paris he adopted the position of a young naif amongst a crowd of predominantly older homosexual men, to whom his unworldliness was irresistibly compelling. Cocteau affectionately declared in a catalogue preface for Wood's first major exhibition in Britain, shared with the Nicholsons: 'In Christopher Wood there is no malice. There is a frankness, a naivety of a young dog who has not had the illness of time'.

Written in 1927, this comment only partially rings true since by this time Wood had inevitably become embroiled in the drug-fuelled hedonism of the Parisian avant-garde. However he did at least continue to uphold purity in his paintings. A review in the New Statesman remarked: 'The dry winds of the continent have blown away from his canvases some traces of the fog that besets these islands, but they have a gay humour which is essentially English.' Cocteau too emphasised the importance of his nationality, which he believed set him apart from his peers in Paris, asserting 'Wood is an English painter; his work is reticent, it takes exercise in the fresh air'.

These responses seemed to anticipate Wood's next significant series of paintings, created during his visit to the Nicholsons' farmhouse in Cumbria in the spring of 1928. Here he worked side by side with Ben, learning to eliminate detail through the method of reducing his subjects to fluid, continuous contours. In part Wood's pictures were a true reflection of the Nicholsons' modest and elemental surroundings, but they also demonstrate his efforts to return to a state of innocence.

His representations of farmsteads as simplified box-shapes and animals as crudely drawn profiles have a certain naïve charm that is comparable to children's drawings, whilst his brush marks appear intuitive and spontaneous. It was also during his visit to Bankshead that Wood started to prepare his canvases with a thick primer called Coverine, into which he scraped in order to create a rough surface, leaving areas of the preparatory grounds exposed.

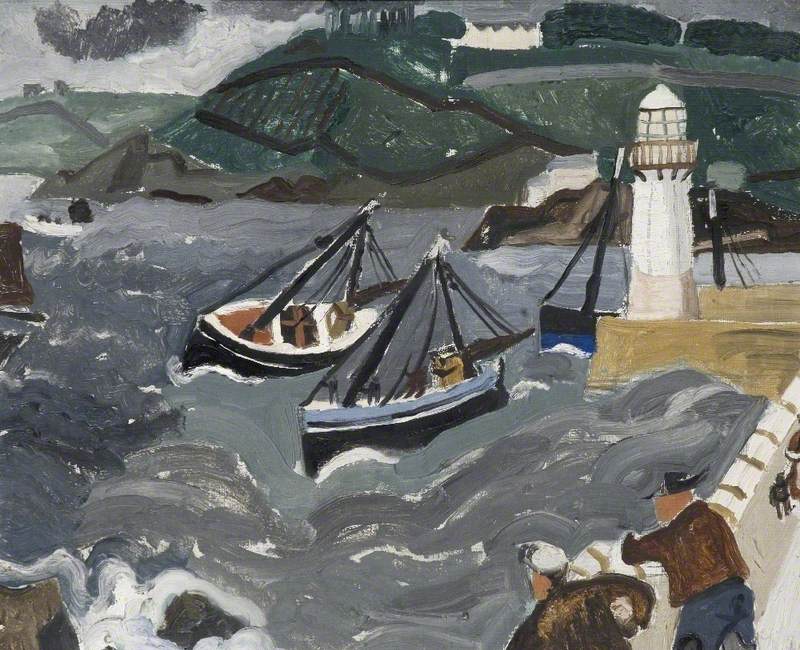

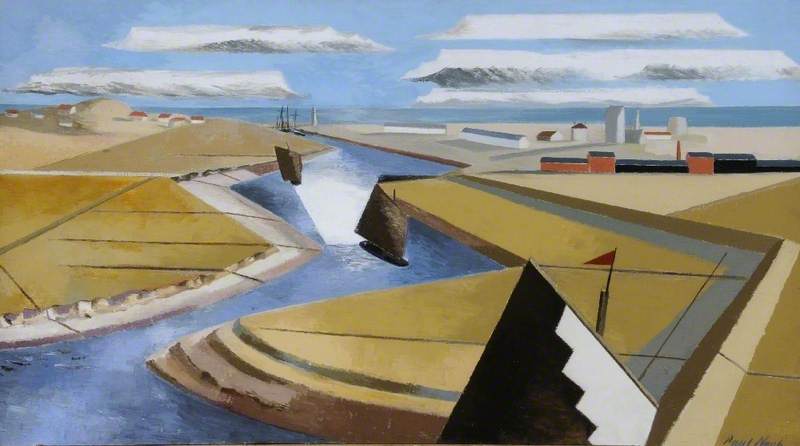

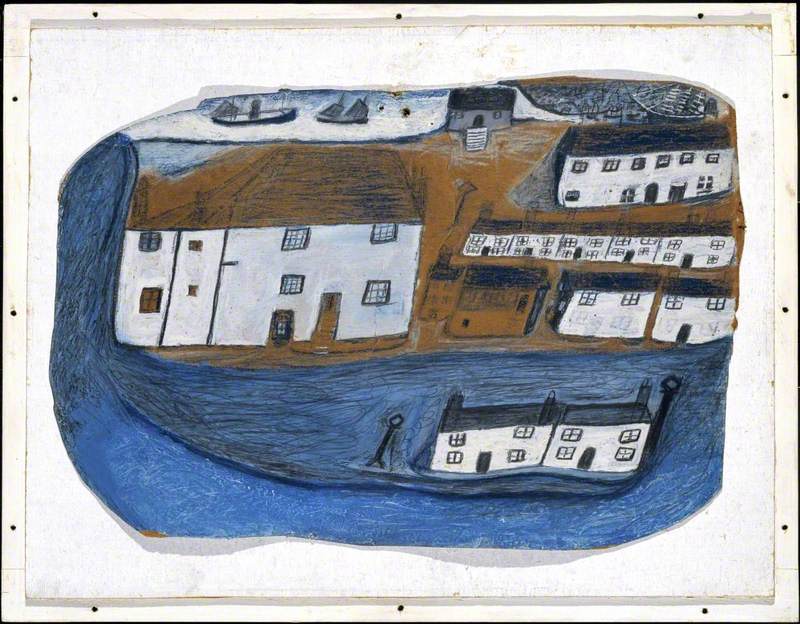

Wood's new focus on the texture and materiality of his pictures would develop further following his 'discovery' of the self-taught painter Alfred Wallis during a visit to St Ives with Ben Nicholson in the summer of 1928. Staying close to the retired seaman's home, a humble terrace in Back Road West, Wood visited Wallis almost daily, taking direct inspiration from the unique and visionary pictures he discovered there. To 'sophisticated' artists such as the Nicholsons and Wood, Wallis' depictions of flattened sailing vessels painted on salvaged pieces of driftwood and cardboard spoke of creativity unspoilt by academic training or 'civilised' culture.

In this regard his art was genuinely naïve, but it was nonetheless based on his authentic experience of sailing great schooners and brigantines during the heyday of the Atlantic fishing industry. As Wood observed there was also a certain literalness in his treatment of materials, no doubt derived from the fact that he applied the same paints in his pictures as he did to real boats.

In his own depictions of the harbour in St Ives, Wood unashamedly replicated Wallis' pictures, appropriating his simple iconography and unsophisticated techniques. In a letter to Winifred Nicholson he commented that he was painting 'more & more influence de Wallis', and described how he mixed colour with black and white, an approach that demonstrated surprising disregard for the modernist principles of pure colour.

In one particularly Wallis-esque painting, Harbour in Hills (1928), Wood represented the sea as a swirling variation of light greys and deep charcoals, which seems to suggest that he had taken to mixing his pigments directly on the surface of his pictures, just as Wallis did.

Meanwhile the intensity with which Wood painted the dark green banks seems to bear at least some likeness to Van Gogh's Provençal landscapes.

In this respect it is possible that Wallis' Spartan existence also reminded him of the Post-Impressionist's primitive return to nature. Wood certainly put the two painters together in his mind when he wrote to Jim Ede: 'I am not surprised that no one likes Wallis, no one liked Van Gogh for a long time did they?'

Back in Paris, Wood became increasingly aware that the excessive lifestyle of his artistic friends threatened the virtuousness he was aspiring to achieve. In order to maintain a sense of balance the artist resigned himself to dividing his existence between two extremes, oscillating between periods of solitude when he could focus on his creative output and those centring on his social life. The problem was that the drug opium featured in both aspects and, whilst in Paris he was able to keep his intake pure with supplies from friends, when alone he was more inclined to smoke the dross from old pipes.

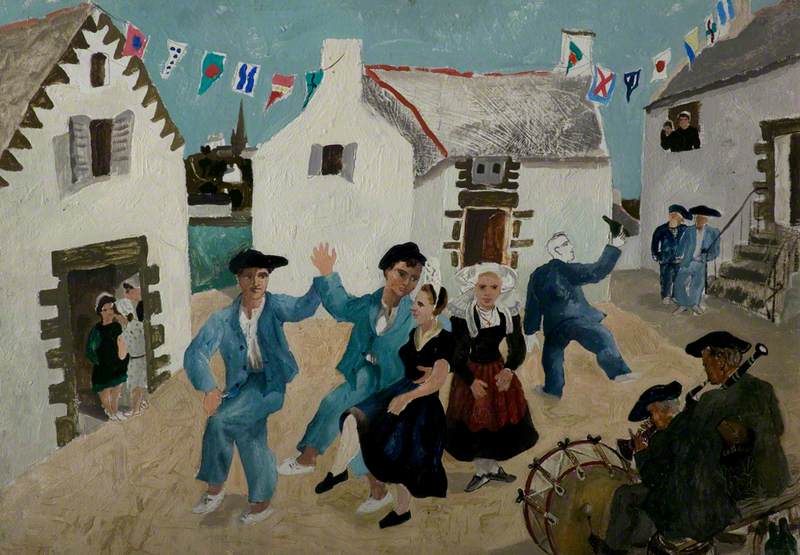

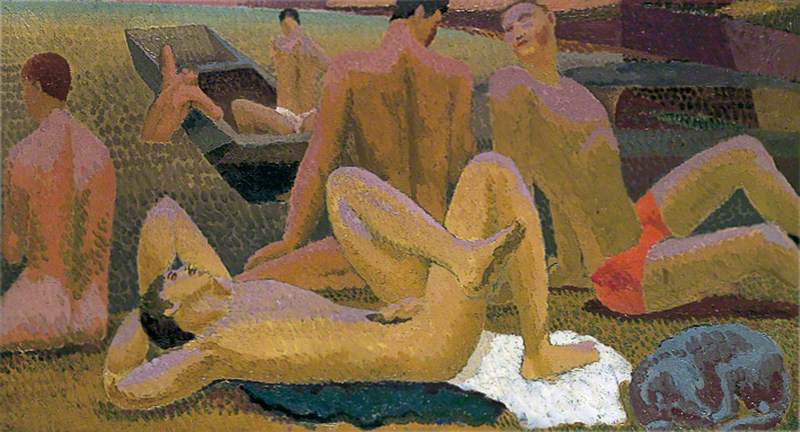

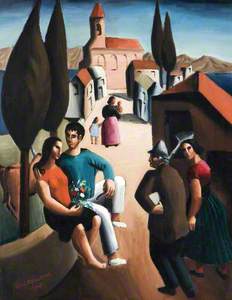

The effect of Wood's extreme isolation and the heightened sensory awareness that came from his drug consumption resulted in the singular appearance of his final series of around 40 pictures, which were painted in Treboul, Brittany in as little as six weeks during the summer of 1930. Focusing on the Breton people as his subject, perhaps one of his greatest accomplishments was the symbolic evocation of their religious beliefs that underpinned the Celtic seafaring customs.

In these paintings a deep spirituality is embedded within the everyday social lives of the fisher people, echoing Gauguin's treatment of comparable subjects in Pont Aven. There are similarities too between Wood's approach and the way that Van Gogh achieved a perfect synthesis between his artistic style and moral values. In Wood's work the direct application of colour and form was in perfect harmony with the modest piety of the Breton people, representing a realisation of the simple, intuitive vision for which he had been striving throughout his career.

Shortly after completing his final pictures, on 19th August 1930 Wood took a train from Paris to Le Havre, and from there travelled to Southampton before finally reaching Salisbury. At 2.10pm, just as the Atlantic Coast Express drew up into the station platform, Wood jumped in front of the train to his death.

In the years following his suicide the British art world attempted to map the significance of his unique career, during a period in which his naïve style was quickly negated by the new trend for abstraction. Nevertheless, it was Wood's engagement with the pervading interest in Primitivism on both sides of the channel that was instrumental to changing the insular atmosphere of the British art world, thus paving the way for the progressive forms of modernism that developed in Britain during the 1930s.

Katy Norris, Curator at Pallant House Gallery

'Christopher Wood: Sophisticated Primitive' ran from 2nd July to 2nd October 2016. An accompanying illustrated monograph published by Lund Humphries is available in the Pallant House Gallery Bookshop.

This article was originally published in the Pallant House Gallery Magazine, issue No.39.